Galantamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Razadyne |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699058 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80 to 100% |

| Protein binding | 18% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic partially CYP450:CYP2D6/3A4 substrate |

| Biological half-life | 7 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (95%, of which 32% unchanged), fecal (5%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.118.289 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H21NO3 |

| Molar mass | 287.354 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 126.5 °C (259.7 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Galantamine (Nivalin, Razadyne, Razadyne ER, Reminyl, Lycoremine) is used for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease and various other memory impairments, in particular those of vascular origin. It is an alkaloid that has been isolated from the bulbs and flowers of Galanthus caucasicus (Caucasian snowdrop), Galanthus woronowii (Voronov's snowdrop), and some other members of the family Amaryllidaceae such as Narcissus (daffodil), Leucojum aestivum (snowflake), and Lycoris including Lycoris radiata (red spider lily).[1] It can also be produced synthetically.

Studies of usage in modern medicine began in the Soviet Union in the 1950s. The active ingredient was extracted, identified, and studied, in particular in relation to its acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-inhibiting properties. The bulk of the work was carried out by Soviet pharmacologists M. D. Mashkovsky and R. P. Kruglikova–Lvova, beginning in 1951.[2] The work of Mashkovsky and Kruglikova-Lvova was the first published work that demonstrated the AChE-inhibiting properties of galantamine.[3]

The first industrial process was developed in Bulgaria by prof. Paskov in 1959 (Nivalin, Sopharma) from a species traditionally used as a popular medicine in Eastern Europe, and, thus, the idea for developing a medicine from these species seems to be based on the local use (i.e., an ethnobotany-driven drug discovery).[4][5]

In addition to uses in Alzheimer's disease, galantamine has been used to treat myasthenia, myopathy, muscular dystrophy, and sensory and motor dysfunction associated with disorders of the central nervous system. Research has indicated that galantamine may prove useful both in the treatment of organophosphate poisoning and in the treatment of autism in children and adolescents.

Uses in mythology

In Homer's Odyssey the god Hermes gives Odysseus an herb with "a black root, but milklike flower" called "moly", which Hermes claims will make Odysseus immune to the sorceress Cerce's drugs. It is believed that moly is the snowdrop Galanthus nivalis, which is a source of galantamine.[6] The descriptions of moly given by Greek physician and herbalist Dioscorides support moly's identity as Galanthus nivalis.[6] It has been proposed that the drugs Cerce used were an extract from Datura stramonium (also known as jimsonweed), which causes memory loss and delirium.[6] This would give a basis for the snowdrop's use as an antidote, as Datura stramonium is anticholinergic, while galantamine is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.[6]

Medical uses

| Uses | |

|---|---|

| treatment of dementia caused by Alzheimer's disease[7] | |

| Who might take | |

| adults who have mid-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease as indicated by the Mini–mental state examination[7] | |

| Precautions | |

| |

| Other options | |

|

Galantamine is indicated for the treatment of mild to moderate vascular dementia and Alzheimer's.[8][9] In the US, it is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. In Austria the drug is approved for muscular dystrophy. Research has indicated that galantamine may also prove useful in the treatment of organophosphate poisoning.[10] Galantamine has been used in Eastern Europe to treat neuromuscular diseases including muscular dystrophy and myasthenia, however this has not lead to widespread use.[11]

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease is characterized by the impairment of cholinergic function. One hypothesis is that this impairment contributes to the cognitive deficits caused by the disease. This hypothesis forms the basis for galantamine's use as a cholinergic enhancer in the treatment of Alzheimer's. Galantamine completely inhibits acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme which hydrolyzes acetylcholine. As a result of acetylcholinesterase inhibition, galantamine increases the availability of acetylcholine for synaptic transmission.[12] Additionally, galantamine binds to the allosteric sites of nicotinic receptors, which causes a conformational change.[13] This allosteric modulation increases the nicotinic receptor's response to acetylcholine.[12] The activation of presynaptic nicotinic receptors increases the release of acetylcholine, further increasing the availability of acetylcholine.[12] Galantamine's competitive inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and allosteric nicotinic modulation serves as a dual mechanism of action.[13]

To reduce the prevalence of negative side effects associated with galantamine, such as nausea and vomiting, a dose-escalation scheme may be used.[14] The use of a dose-escalation scheme has been well accepted in countries where galantamine is used.[14] A dose-escalation scheme for Alzheimer's treatment involves a recommended starting dosage of 4mg galantamine tablets given twice a day (8 mg/day).[15] After a minimum of 4 weeks, the dosage may then be increased to 8 mg given twice a day (16 mg/day).[15] After a minimum of 4 weeks at 16 mg/day, the treatment may be increased to 12 mg given twice a day (24 mg/day).[15] Dosage increases are based upon the assessment of clinical benefit as well as tolerability of the previous dosage.[15] If treatment is interrupted for more than three days, the process is usually restarted, beginning at the starting dosage, and re-escalating to the current dose.[15]

Available forms

The product is supplied in both a prescription form as well as an over the counter supplement in twice-a-day tablets, in once-a-day extended-release capsules, and in oral solution.

Side effects

Galantamine's side effect profile was very similar to that of other cholinesterase inhibitors, with gastrointestinal symptoms being the most notable and most commonly observed. One study reports higher proportions of patients treated with galantamine experiencing nausea and vomiting as opposed to the placebo group.[14] Another study using a dose-escalation treatment has found that incidences of nausea would decrease to baseline levels soon after each increase in administered dosage.[13] In practice, some other cholinesterase inhibitors might be better tolerated; however, a careful and gradual titration over more than three months may lead to equivalent long-term tolerability.[16]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and international health authorities have published an alert of galantamine based on data from two studies during the treatment for mild cognitive impairment (MCI); higher mortality rates were seen in drug-treated patients.[17][18] On April 27, 2006, FDA approved labeling changes concerning all form of galantamine preparations (liquid, regular tablets, and extended release tablets) warning of the risk of bradycardia (slow resting heart rate), and sometimes atrioventricular block, especially in predisposed persons. At the same time, the risk of syncope (fainting) seems to be increased relative to placebo. "In randomized controlled trials, bradycardia was reported more frequently in galantamine-treated patients than in placebo-treated patients, but was rarely severe and rarely led to treatment discontinuation"[19] These side effects have not been reported in Alzheimer's Disease related studies.[20]

Pharmacology

Galantamine's chemical structure contains a tertiary amine. At a neutral pH, this tertiary amine will often bond to a hydrogen, and appear mostly as an ammonium ion.[11]

Galantamine is a potent allosteric potentiating ligand of human nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) α4β2, α3β4, and α6β4, and chicken/mouse nAChRs α7/5-HT3 in certain areas of the brain.[21] By binding to the allosteric site of the nAChRs, a conformational change occurs which increases the receptors response to acetylcholine.[12] This modulation of the nicotinic cholinergic receptors on cholinergic neurons in turn causes an increase in the amount of acetylcholine released.[22] Galantamine also works as a weak competitive and reversible cholinesterase inhibitor in all areas of the body.[21] By inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, it increases the concentration and thereby action of acetylcholine in certain parts of the brain. Galantamine's effects on nAChRs and complementary acetylcholinesterase inhibition make up a dual mechanism of action. It is hypothesized that this action might relieve some of the symptoms of Alzheimer's.

Galantamine in its pure form is a white powder. The atomic resolution 3D structure of the complex of galantamine and its target, acetylcholinesterase, was determined by X-ray crystallography in 1999 (PDB code: 1DX6; see complex).[23] There is no evidence that galantamine alters the course of the underlying dementing process.[24]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption of galantamine is rapid and complete and shows linear pharmacokinetics. It is well absorbed with absolute oral bioavailability between 80 and 100%. It has a half-life of seven hours. Peak effect of inhibiting acetylcholinesterase was achieved about one hour after a single oral dose of 8 mg in some healthy volunteers.

The coadministration of food delays the rate of galantamine absorption, but does not affect the extent of absorption.[13]

Plasma protein binding of galantamine is about 18%, which is relatively low.

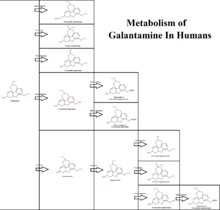

Metabolism

Approximately 75% of a dose of galantamine is metabolised in the liver. In vitro studies have shown that Hepatic CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 are involved in galantamine metabolism. Within 24 hours of intravenous or oral administration approximately 20% of a dose of galantamine will be excreted unreacted in the urine.[13]

In humans, several metabolic pathways for galantamine exist.[25] These pathways lead to the formation of a number of different metabolites.[25] One of the metabolites that may result can be formed through the glucuronidation of galantamine.[25] Additionally, galantamine may undergo oxidation or demethylation at its nitrogen atom, forming two other possible metabolites.[25] Galantamine can undergo demethylation at its oxygen atom, forming an intermediate which can then undergo glucuronidation or sulfate conjugation.[25] Lastly, galantamine may be oxidized and then reduced before finally undergoing demethylation or oxidation at its nitrogen atom, or demethylation and subsequent glucuronidation at its oxygen atom.[25]

For Razadyne ER, the once-a-day formulation, CYP2D6 poor metabolizers had drug exposures that were approximately 50% higher than for extensive metabolizers. About 7% of the population has this genetic mutation; however, because the drug is individually titrated to tolerability, no specific dosage adjustment is necessary for this population.

Drug interactions

Since galantamine in metabolized by CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, inhibiting either of these isoenzymes will increase the cholinergic effects of galantamine.[13] Inhibiting these enzymes may lead to adverse effects.[13] It was found that paroxetine, an inhibitor of CYP2D6, increased the bioavailability of galantamine by 40%.[13] The CYP3A4 inhibitors ketoconazole and erythromycin increased the bioavailability of galantamine by 30% and 12%, respectively.[13]

Synthesis

Galantamine is produced from natural resources and a patented total synthesis process. Many other synthetic methods exist but have not been implemented on an industrial scale.

Research

Organophosphate poisoning

The toxicity of organophosphates results primarily from their action as irreversible inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase.[10] Inhibiting acetylcholinesterase causes an increase in acetylcholine, as the enzyme is no longer available to catalyze its breakdown.[10] In the peripheral nervous system, acetylcholine accumulation can cause an overstimulation of muscarinic receptors followed by a desensitization of nicotinic receptors.[10] This leads to severe skeletal muscle fasciculations (involuntary contractions).[10] The effects on the central nervous system include anxiety, restlessness, confusion, ataxia, tremors, seizures, cardiorespiratory paralysis, and coma.[10] As a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, galantamine has the potential to serve as an effective organophosphate poisoning treatment by preventing irreversible acetylcholinesterase inhibition.[10] Additionally, galantamine has anticonvulsant properties which may make it even more desirable as an antidote.[10]

Research supported in part by the US Army has led to a US patent application for the use of galantamine and/or its derivatives for treatment of organophosphate poisoning. The indications for use of galantamine in the patent application include poisoning by nerve agents "including but not limited to soman, sarin, and VX, tabun, and Novichok agents". Galantamine was studied in the research cited in the patent application for use along with the well-recognized nerve agent antidote atropine. According to the investigators, an unexpected synergistic interaction occurred between galantamine and atropine in an amount of 6 mg/kg or higher. Increasing the dose of galantamine from 5 to 8 mg/kg decreased the dose of atropine needed to protect experimental animals from the toxicity of soman in dosages 1.5.times the dose generally required to kill half the experimental animals.[26]

Autism

Galantamine given in addition to risperidone to autistic children has been shown to improve some of the symptoms of autism such as irritability, lethargy, and social withdrawal.[27] Additionally, the cholinergic and nicotinic receptors are believed to play a role in attentional processes.[28] Some studies have noted that cholinergic and nicotinic treatments have improved attention in autistic children.[28] As such, it is hypothesized that galantamine's dual action mechanism might have a similar effect in treating autistic children and adolescents.[28]

Anesthesia

Galantamine may have some limited use in reducing the side-effects of anesthetics ketalar and diazepam. In one study, a control group of patients were given ketalar and diazepam and underwent anesthesia and surgery.[29] The experimental group was given ketalar, diazepam, and nivalin (of which the active ingredient is galantamine).[29] The degree of drowsiness and disorientation of the two groups was then assessed 5, 10, 15, 30 and 60 minutes after surgery.[29] The group that had taken nivalin were found to be more alert 5, 10, and 15 minutes after the surgery.[29]

References

- ↑ NNFCC Project Factsheet: Sustainable Production of the Natural Product Galanthamine (Defra), NF0612

- ↑ Heinrich, M. (2004). "Snowdrops: The heralds of spring and a modern drug for Alzheimer's disease". Pharmaceutical Journal. 273 (7330): 905–6. OCLC 98892008.

- ↑ Mashkovsky, MD; Kruglikova–Lvova, RP (1951). "On the pharmacology of the new alkaloid galantamine". Farmakologia Toxicologia. 14: 27–30.

- ↑ Heinrich, M.; Teoh, H.L. (2004). "Galanthamine from snowdrop – the development of a modern drug against Alzheimer's disease from local Caucasian knowledge". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 92 (2–3): 147–162. PMID 15137996. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.012.

- ↑ Scott, LJ; Goa, KL (2000). "Galantamine: a review of its use in Alzheimer's disease". Drugs. 60 (5): 1095–122. PMID 11129124. doi:10.2165/00003495-200060050-00008.

- 1 2 3 4 Block, Will. "Galantamine, the Odyssey's Nootropic Phytonutrient, Revives Memory and Helps Fight Alzheimer's Disease". Life enhancement. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Informulary (April 2014). "Drug Facts Box: Razadyne (galantamine)" (PDF). Consumer Reports. Consumer Reports. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ Galantamine Benefits Both Alzheimer's Disease and Vascular Dementia

- ↑ Galantamine Improves Attention in Alzheimer's

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Albuquerque, E. X., Pereira, E. F. R., Aracava, Y., Fawcett, W. P., Oliveira, M., Randall, W. R., ... Adler, M. (2006). Effective countermeasure against poisoning by organophosphorus insecticides and nerve agents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(35), 13220–13225. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0605370103

- 1 2 Cronin, Joseph R. (December 2001). "The Plant Alkaloid Galantamine". Alternative and Complementary Therapies. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Raskind, M.A.; Peskind, E.R.; Wessel, T.; Yuan, W. (June 27, 2000). "Galantamine in AD". Neurology. 54 (12): 2261–2268. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Farlow, M.R. Clin Pharmacokinet (2003) 42: 1383. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342150-00005

- 1 2 3 Erkinjuntti, Timo; Kurz, Alexander; Gauthier, Serge; Bullock, Roger; Lilienfeld, Sean; Damaraju, ChandrasekharRao Venkata (13 April 2002). "Efficacy of galantamine in probable vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease combined with cerebrovascular disease: a randomised trial". The Lancet. 359 (9314): 1283–1290. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Galantamine Dosage and Administration". Drugs.com. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ Birks, J; Birks, Jacqueline (2006). Birks, Jacqueline, ed. "Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD005593. PMID 16437532. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005593.

- ↑ "FDA ALERT: Galantamine hydrobromide (marketed as Razadyne, formerly Reminyl) - Healthcare Professional Sheet" (PDF). Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers. Food and Drug Administration. May 2005. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ↑ "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products > Reminyl (galantamine hydrobromide)". # MedWatch The FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program. Food and Drug Administration. March 2005. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- ↑ "Safety Labeling Changes Approved By FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER)". MedWatch, The FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program. Food and Drug Administration. April 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ↑ "Safety information from Investigational Studies with REMINYL (galantamine hydrobromide) in Mild Cognitive Impairment". Janssen-Ortho Inc. 2005-04-22. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- 1 2 Samochocki, Marek; Höffle, Anja; Fehrenbacher, Andreas; Jostock, Ruth; Ludwig, Jürgen; Christner, Claudia; Radina, Martin; Zerlin, Marion; Ullmer, Christoph; Pereira, Edna F. R.; Lübbert, Hermann; Albuquerque, Edson X.; Maelicke, Alfred (2003). "Galantamine Is an Allosterically Potentiating Ligand of Neuronal Nicotinic but Not of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 305 (3): 1024–36. PMID 12649296. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.045773.

- ↑ Woodruff-Pak, Diana S.; Vogel, Richard W.; Wenk, Gary L. (2001). "Galantamine: Effect on nicotinic receptor binding, acetylcholinesterase inhibition, and learning". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (4): 2089–94. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.2089W. JSTOR 3055005. PMC 29386

. PMID 11172080. doi:10.1073/pnas.031584398.

. PMID 11172080. doi:10.1073/pnas.031584398. - ↑ Greenblatt, H.M.; Kryger, G.; Lewis, T.; Silman, I.; Sussman, J.L. (1999). "Structure of acetylcholinesterase complexed with (−)-galanthamine at 2.3 Å resolution". FEBS Letters. 463 (3): 321–6. PMID 10606746. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01637-3.

- ↑ Ortho-McNeil Neurologics, "Razadyne ER US Product Insert", May 2006

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 G. S. J. Mannens, C. A. W. Snel, J. Hendrickx, T. Verhaeghe, L. Le Jeune, W. Bode, L. van Beijsterveldt, K. Lavrijsen, J. Leempoels, N. Van Osselaer, A. Van Peer and W. Meuldermans. The Metabolism and Excretion of Galantamine in Rats, Dogs, and Humans. Drug Metabolism and Disposition May 1, 2002, 30 (5) 553-563; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.30.5.553

- ↑ Albuquerque, Edson X; Adler, Michael; Pereira, Edna F.R. (January 22, 2009). "United States Patent Application 20090023706". US Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Ghaleiha, A; Ghyasvand, M; Mohammadi, M. R.; Farokhnia, M; Yadegari, N; Tabrizi, M; Hajiaghaee, R; Yekehtaz, H; Akhondzadeh, S (2013). "Galantamine efficacy and tolerability as an augmentative therapy in autistic children: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 28 (7): 677–685. PMID 24132248. doi:10.1177/0269881113508830.

- 1 2 3 Nicolson, Rob; Craven-Thuss, Beth; Smith, Judy (2006). "A Prospective, Open-Label Trial of Galantamine in Autistic Disorder". JOURNAL OF CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY. 16 (5): 621–629. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Chakalova E, Marinova M, Srebreva M, Anastasov D, Ploskov K. (1987). "Attempt to eliminate residual somnolence and disorientation with nivaline after anesthesia with ketalar and diazepam for minor obstetrical and gynecologic surgery". Akush Ginekol (Sofiia). 26 (3): 28–31. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

External links

- Razadyne ER (manufacturer's website)

- Proteopedia 1dx6

- AChE inhibitors and substrates (Part II)

- Acetylcholinesterase: A gorge-ous enzyme PDB Structure article at PDBe