Gabbro

Gabbro ( /ˈɡæbroʊ/) refers to a large group of dark, often phaneritic (coarse-grained), mafic intrusive igneous rocks chemically equivalent to basalt. It forms when molten magma is trapped beneath the Earth's surface and slowly cools into a holocrystalline mass.

Much of the Earth's oceanic crust is made of gabbro, formed at mid-ocean ridges. Gabbro is also found as plutons associated with continental volcanism. Due to its variant nature, the term "gabbro" may be applied loosely to a wide range of intrusive rocks, many of which are merely "gabbroic".

Etymology

The term "gabbro" was used in the 1760s to name a set of rock types that were found in the ophiolites of the Apennine Mountains in Italy.[1] Then, in 1809, the German geologist Christian Leopold von Buch used the term more restrictively in his description of these Italian ophiolitic rocks.[2] He assigned the name "gabbro" to rocks that geologists nowadays would more strictly call "metagabbro" (metamorphosed gabbro).[3] Von Buch named gabbro after Gabbro, a village in Rosignano Marittimo municipality of Tuscany.

Petrology

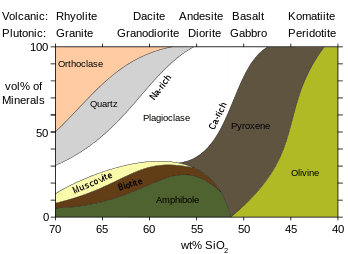

Gabbro is dense, greenish or dark-colored and contains pyroxene, plagioclase, and minor amounts of amphibole and olivine.

The pyroxene content is mostly clinopyroxene, generally augite, but small amounts of orthopyroxene may also be present. If the amount of orthopyroxene is more than 95% of the total pyroxene content (5% or less clinopyroxene content), then the rock is termed norite. On the other hand, gabbro has more than 95% of its pyroxenes in the form of the monoclinic clinopyroxene/s. Intermediate rocks are termed gabbro-norite. The calcium rich plagioclase feldspar (labradorite-bytownite) and pyroxene content vary between 10–90% in gabbro. If more than 90% plagioclase is present, then the rock is an anorthosite. If on the other hand, the rock contains more than 90% pyroxenes (often both are present), it is termed pyroxenite. Gabbro may also contain small amounts of olivine ("olivine gabbro" if substantial amount of olivine is present), amphibole and biotite. The quartz content in gabbro is less than 5% of total volume. 'Quartz gabbros' or monzogabbros are also known to occur, for example the cizlakite at Pohorje in northeastern Slovenia,[4] and are probably derived from magma that was over-saturated with silica. Essexites represent gabbros whose parent magma was under-saturated with silica, resulting in the formation of the feldspathoid minerals nepheline, cancrinite, and sodalite as accessory minerals rather than quartz. (Silica saturation of a rock can be evaluated by normative mineralogy). Gabbros contain minor amounts, typically a few percent, of iron-titanium oxides such as magnetite, ilmenite, and ulvospinel.

Gabbro is generally coarse grained, with crystals in the size range of 1 mm or greater. Finer grained equivalents of gabbro are called diabase (also known as dolerite), although the term microgabbro is often used when extra descriptiveness is desired. Gabbro may be extremely coarse grained to pegmatitic, and some pyroxene-plagioclase cumulates are essentially coarse grained gabbro, some may exhibit acicular crystal habits.

Gabbro is usually equigranular in texture, although it may be porphyritic at times, especially when plagioclase oikocrysts have grown earlier than the groundmass minerals.

Distribution

Gabbro can be formed as a massive, uniform intrusion via in-situ crystallisation of pyroxene and plagioclase, or as part of a layered intrusion as a cumulate formed by settling of pyroxene and plagioclase. Cumulate gabbros are more properly termed pyroxene-plagioclase adcumulate.

Gabbro is an essential part of the oceanic crust, and can be found in many ophiolite complexes as parts of zones III and IV (sheeted dyke zone to massive gabbro zone). Long belts of gabbroic intrusions are typically formed at proto-rift zones and around ancient rift zone margins, intruding into the rift flanks. Mantle plume hypotheses may rely on identifying mafic and ultramafic intrusions and coeval basalt volcanism.

Nearly all gabbros are found in plutonic bodies, but to restrict the term (as the International Union of Geological Sciences, IUGS, suggests) just to plutonic rocks is inappropriate, because gabbro may be found as a coarse- grained interior facies of certain thick lavas (see, for example[5]). It is better to base a rock definition on descriptive characteristics of the rock rather than how or where it was formed.[6]

Uses

Gabbro often contains valuable amounts of chromium, nickel, cobalt, gold, silver, platinum, and copper sulfides.

Ocellar (orbicular) varieties of gabbro can be used as ornamental facing stones, paving stones and it is also known by the trade name of 'black granite', which is a popular type of graveyard headstone used in funerary rites. It is also used in kitchens and their countertops, also under the misnomer of 'black granite'.

See also

References

- ↑ Bortolotti, V. et al. Chapter 11: Ophiolites, Ligurides and the tectonic evolution from spreading to convergence of a Mesozoic Western Tethys segment in F. Vai, G.P. and Martini, I.P. (editors) (2001) Anatomy of an Orogen: The Apennines and Adjacent Mediterranean Basins, Dordrecht, Springer Science and Business Media, p. 151. ISBN 978-90-481-4020-6

- ↑ Bortolotti, V. et al. Chapter 11: Ophiolites, Ligurides and the tectonic evolution from spreading to convergence of a Mesozoic Western Tethys segment in F. Vai, G.P. and Martini, I.P. (editors) (2001) Anatomy of an Orogen: The Apennines and Adjacent Mediterranean Basins, Dordrecht, Springer Science and Business Media, p. 152. ISBN 978-90-481-4020-6

- ↑ Gabbro at SandAtlas geology blog. Retrieved on 2015-07-09.

- ↑ Le Maitre, R. W.; et al., eds., 2005, Igneous Rocks: A Classification and Glossary of Terms, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2nd ed., p. 69, ISBN 9780521619486

- ↑ Arndt et al., 1977, Komatiitic and iron-rich tholeiitic lavas of Munro Township, northeast Ontario: J. Petrol., v. 18, pp. 319–69

- ↑ Robin Gill. Igneous Rocks and Processes, 2010

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gabbro. |