Fusiform gyrus

| Fusiform gyrus | |

|---|---|

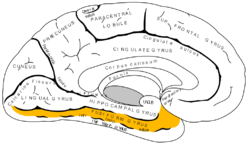

Medial surface of left cerebral hemisphere. (Fusiform gyrus shown in orange) | |

Medial surface of right cerebral hemisphere. (Fusiform gyrus visible near bottom) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | gyrus fusiformis |

| NeuroNames | hier-121 |

| NeuroLex ID | Fusiform Gyrus |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | g_13/12405287 |

| TA | A14.1.09.227 |

| FMA | 61908 |

The fusiform gyrus, also known as the (discontinuous) occipitotemporal gyrus, is part of the temporal lobe and occipital lobe in Brodmann area 37.[1] The fusiform gyrus is located between the lingual gyrus and parahippocampal gyrus above, and the inferior temporal gyrus below.[2] Though the functionality of the fusiform gyrus is not fully understood, it has been linked with various neural pathways related to recognition. Additionally, it has been linked to various neurological phenomena such as synesthesia, dyslexia, and prosopagnosia.

Anatomy

Anatomically, the fusiform gyrus is the largest macro-anatomical structure within the ventral temporal cortex, which mainly includes structures involved in high-level vision.[3][4] The term fusiform gyrus (lit. „spindle-shaped convolution“) refers to the fact that the shape of the gyrus is wider at its centre than at its ends. This term is based on the description of the gyrus by Emil Huschke in 1854.[4] (see also section on history). The fusiform gyrus is situated at the basal surface of the temporal and occipital lobes and is delineated by the collateral sulcus (CoS) and occipitotemporal sulcus (OTS), respectively.[5] The OTS separates the fusiform gyrus from the inferior temporal gyrus (located laterally in respect to the fusiform gyrus) and the CoS separates the fusiform gyrus from the parahippocampal gyrus (located medially in respect to the fusiform gyrus).

| Inferior views of the fusiform gyrus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The fusiform gyrus can be further delineated into a lateral and medial portion, as it is separated in its middle by the relatively shallow mid-fusiform sulcus (MFS).[6][7][8] Thus, the lateral fusiform gyrus is delineated by the OTS laterally and the MFS medially. Likewise, the medial fusiform gyrus is delineated by the MFS laterally and the CoS medially.

Importantly, the mid-fusiform sulcus serves as a macroanatomical landmark for the fusiform face area (FFA), a functional subregion of the fusiform gyrus assumed to play a key role in processing faces.[3][9]

History

The fusiform gyrus has a contentious history that has recently been clarified. The term was first used in 1854 by Emil Huschke from Jena, Germany, who called the fusiform gyrus a “Spindelwulst” (lit. spindle bulge). He chose this term because of the similarity that the respective cerebral gyrus bears to the shape of a spindle, or fusil, due to its wider central section.[4] At first, researchers located the fusiform gyrus in other mammals as well, without taking into account the variations in gross organizations of other species’ brains. Today, the fusiform gyrus is considered to be specific to hominoids. This is supported by research showing only three temporal gyri and no fusiform gyrus in macaques.[7]

The first accurate definition of the mid-fusiform sulcus was coined by Gustav Retzius in 1896. He was the first to describe the sulcus sagittalis gyri fusiformis (today: mid-fusiform sulcus), and correctly determined that a sulcus divides the fusiform gyrus into lateral and medial partitions. W. Julius Mickle mentioned the mid-fusiform sulcus in 1897 and attempted to clarify the relation between temporal sulci and the fusiform gyrus, calling it the “intra-gyral sulcus of the fusiform lobule”.[4]

Function

The exact functionality of the fusiform gyrus is still disputed, but there is relative consensus on its involvement in the following pathways:

Processing of color information

(see Color center)

In 2003, V.S. Ramachandran collaborated with scientists from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in order to identify the potential role of the fusiform gyrus within the color processing pathway in the brain. Examining the relationship within the pathway specifically in cases of synesthesia, Ramachandran found that synesthetes on average have a higher density of fibers surrounding the angular gyrus. The angular gyrus is involved in higher processing of colors.[10] The fibers relay shape information from the fusiform gyrus to the angular gyrus in order to produce the association of colors and shapes in grapheme-color synesthesia.[10] Cross-activation between the angular and fusiform gyri has been observed in the average brain, implying that the fusiform gyrus regularly communicates with the visual pathway.[11]

Face and body recognition

(see Fusiform face area)

Portions of the fusiform gyrus are critical for face and body recognition.

Word recognition

(see Visual word form area)

It is believed that portions of the left hemisphere fusiform gyrus are used in word recognition.

Within-category identification

After further research by scientists at MIT, it was concluded that both the left and right fusiform gyrus played different roles from one another, but were subsequently interlinked. The left fusiform gyrus plays the role of recognizing "face-like" features in objects that may or may not be actual faces whereas the right fusiform gyrus plays the role in determining whether or not the recognized "face-like" feature is, in fact, an actual face.[12]

Related neural transmitter system

In a 2015 study, dopamine was proposed to play a key role in face recognition task, and was considered to be related to neural activity in fusiform gyrus. By studying the correlation between the binding potential (BP) of dopamine D1 receptor by PET and blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) in fMRI scan during a face recognition task, higher availability of D1 receptor was shown to be associated with higher BOLD level. This study showed that this association with D1 BP is only significant for FFG, not other brain regions. The researchers also showed the possibility that higher availability of dopamine D1 receptor may underlie better performance in face recognition task.[13]

Why is dopamine release linked to face recognition related BOLD activity? Dopamine is known to be related to the reward system. Dopaminergic system shows active response to stimuli that predict possible rewards. As a social demand, face recognition task could be a cognition process that involves dopamine, which can elicit a reinforcement feedback.[13][14]

But how may dopamine regulate FFG activity during face recognition task? A 2007 study indicates that BOLD activity can be modulated by dopamine’s influence on postsynaptic D1 receptors. The regulation is achieved in a way that dopamine first influence post-synaptic potential, and then further cause BOLD activity increase in the local area. This link between post-synaptic BOLD activity increase and dopamine release can be explained by blockage of dopamine reuptake.[15]

Associated neurological phenomena

The fusiform gyrus has been speculated to be associated with various neurological phenomena. Many are outlined below:

Prosopagnosia

Some researchers think that the fusiform gyrus may be related to the disorder known as prosopagnosia, or face blindness. Research has also shown that the fusiform face area, the area within the fusiform gyrus, is heavily involved in face perception but only to any generic within-category identification that is shown to be one of the functions of the fusiform gyrus.[16] Abnormalities of the fusiform gyrus have also been linked to Williams syndrome.[17] Fusiform gyrus has also been involved in the perception of emotions in facial stimuli.[18] However, individuals with autism show little to no activation in the fusiform gyrus in response to seeing a human face.[19]

Synaesthesia

Recent research has seen activation of the fusiform gyrus during subjective grapheme-color perception in people with synaesthesia.[20] The effect of the fusiform gyrus in grapheme sense seems somewhat more clear as the fusiform gyrus seems to play a key role in word recognition. The connection to color may be due to cross wiring of (being directly connected to) areas of the fusiform gyrus and other areas of the visual cortex associated with experiencing color.[21]

Dyslexia

For those with dyslexia, it has been seen that the fusiform gyrus is underactivated and has reduced gray matter density.[22]

Face hallucinations

Increased neurophysiological activity in the fusiform face area may produce hallucinations of faces, whether realistic or cartoonesque, as seen in Charles Bonnet syndrome, hypnagogic hallucinations, peduncular hallucinations, or drug-induced hallucinations.[23]

References

- ↑ Nature Neuroscience, vol7, 2004

- ↑ "Gyrus". The free dictionary. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- 1 2 Weiner, Grill-Spector (2014). "The functional architecture of the ventral temporal cortex and its role in categorization". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 15: 536–548. PMC 4143420

. PMID 24962370. doi:10.1038/nrn3747.

. PMID 24962370. doi:10.1038/nrn3747. - 1 2 3 4 Zilles, Weiner (2015). "The anatomical and functional specialization of the fusiform gyrus". Neuropsychologia. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.033.

- ↑ "Gray’s Anatomy – The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice 41st edition". 26 September 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ Grill-Spector, Weiner; et al. (2013). "The mid-fusiform sulcus: A landmark identifying both cyotarchitectonic and functional divisions of human ventral temporal cortex". NeuroImage. 84: 453–465. PMC 3962787

. PMID 24021838. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.068.

. PMID 24021838. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.068. - 1 2 Nasr (2011). "Scene-selective cortical regions in human and nonhuman primates". J Neurosci. 31 (39): 13771–85. PMC 3489186

. PMID 21957240. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2792-11.2011.

. PMID 21957240. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2792-11.2011. - ↑ Grill-Spector, Weiner (2010). "Sparsely-distributed organization of face and limb activations in human ventral temporal cortex". NeuroImage. 52 (4): 1559–73. PMC 3122128

. PMID 20457261. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.262.

. PMID 20457261. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.262. - ↑ Grill-Spector, Weiner (2012). "The improbable simplicity of the fusiform face area". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 16: 251–254. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.03.003.

- 1 2 Ramachandran, V.S. (January 17, 2011). The Tell Tale Brain. 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 9780393340624.

- ↑ Hubbard EM, Ramachandran VS (November 2005). "Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia" (PDF). Neuron (Review). 48 (3): 509–20. PMID 16269367. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.012.

- ↑ Trafton, A. "How does our brain know what is a face and what’s not?" MIT News

- 1 2 Rypma, Bart; Fischer, Håkan; Rieckmann, Anna; Hubbard, Nicholas A.; Nyberg, Lars; Bäckman, Lars (2015-11-04). "Dopamine D1 Binding Potential Predicts Fusiform BOLD Activity during Face-Recognition Performance". The Journal of Neuroscience. 35 (44): 14702–14707. ISSN 1529-2401. PMC 4635124

. PMID 26538642. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1298-15.2015.

. PMID 26538642. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1298-15.2015. - ↑ Schultz, Wolfram (2007-05-01). "Behavioral dopamine signals". Trends in Neurosciences. 30 (5): 203–210. ISSN 0166-2236. PMID 17400301. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.007.

- ↑ Knutson, Brian; Gibbs, Sasha E. B. (2007-02-06). "Linking nucleus accumbens dopamine and blood oxygenation". Psychopharmacology. 191 (3): 813–822. ISSN 0033-3158. PMID 17279377. doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0686-7.

- ↑ McCarthy, G; et al. (1997). "Face-specific processing in the fuman fusform gyrus". J. Cognitive Neuroscicence. 9: 605–610.

- ↑ A. L. Reiss, et al. Preliminary Evidence Of Abnormal White Matter Related To The Fusiform Gyrus In Williams Syndrome: A Diffusion Tensor Imaging Tractography Study.Genes, Brain & Behavior 11.1, 62–68(2012)

- ↑ Radua, Joaquim; Phillips, Mary L.; Russell, Tamara; Lawrence, Natalia; Marshall, Nicolette; Kalidindi, Sridevi; El-Hage, Wissam; McDonald, Colm; Giampietro, Vincent (2010). "Neural response to specific components of fearful faces in healthy and schizophrenic adults". NeuroImage. 49 (1): 939–946. PMID 19699306. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.030.

- ↑ Carter, Rita. The Human Brain Book. p. 241.

- ↑ Imaging of connectivity in the synaesthetic brain « Neurophilosophy

- ↑ Pujol, J. (2009-04-30). "Study data from J. Pujol and colleagues update understanding of life sciences". Science Letter.

- ↑ Clark, David (2005). The Brain and Behavior. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521549844.

- ↑ Jan Dirk Blom. A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer, 2010, p. 187. ISBN 978-1-4419-1222-0

Additional images

- Fusiform gyrus

Fusiform gyrus animation

Fusiform gyrus animation- Cerebrum.Inferior view. Deep dissection

Fusiform gyrus in a ventral view (from below, diagrammatic), labeled at left

Fusiform gyrus in a ventral view (from below, diagrammatic), labeled at left Fusiform gyrus seen in a ventral view

Fusiform gyrus seen in a ventral view

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fusiform gyrus. |

- Atlas image: n1a2p13 at the University of Michigan Health System – "Cerebral Hemisphere, Inferior View"

- Location at mattababy.org

- 3 clues to understanding your brain , a TED talk by Vilayanur Ramachandran

- What hallucination reveals about our minds, a TED talk by Oliver Sacks

- NIF Search – Fusiform Gyrus via the Neuroscience Information Framework