Frontonasal dysplasia

| Frontonasal dysplasia | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | median cleft face syndrome, frontonasal dysostosis, frontonasal malformation, Tessier cleft number 0/14 |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q75.8 |

| ICD-9-CM | 756.0 |

| OMIM | 136760 |

| MeSH | C538065 |

Frontonasal dysplasia (FND) is a congenital malformation of the midface.[1] For the diagnosis of FND, a patient should present at least two of the following characteristics: hypertelorism (an increased distance between the eyes), a wide nasal root, vertical midline cleft of the nose and/or upper lip, cleft of the wings of the nose, malformed nasal tip, encephalocele (an opening of the skull with protrusion of the brain) or V-shaped hair pattern on the forehead.[1] The cause of FND remains unknown. FND seems to be sporadic (random) and multiple environmental factors are suggested as possible causes for the syndrome. However, in some families multiple cases of FND were reported, which suggests a genetic cause of FND.[2][3]

Signs and symptoms

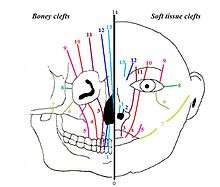

Midfacial malformations can be subdivided into two different groups. One group with hypertelorism, this includes FND. The other with hypotelorism (a decreased distance between the eyes), this includes holoprosencephaly (failure of development of the forebrain).[4] In addition, a facial cleft can be classified using the Tessier classification. Each of the clefts is numbered from 0 to 14. The 15 different types of clefts are then subdivided into 4 groups, based on their anatomical position in the face:[5] midline clefts, paramedian clefts, orbital clefts and lateral clefts. FND is a midline cleft, classified as Tessier 0/14.

Besides this, the additional anomalies seen in FND can be subdivided by region. None of these anomalies are specific for the syndrome of FND, but they do occur more often in patients with FND than in the population. The anomalies that may be present are:

- Nasal: mild anomalies to nostrils that are far apart and a broad nasal root, a notch or cleft of the nose and accessory nasal tags.

- Ocular: narrowed eye slits, almond shaped eyes, epicanthal folds (extra eyelid tissue), epibulbar dermoids (benign tumors of the eye), upper eyelid colombas (full thickness upper eyelid defects), microphtalmos (one or two small eyes), congenital cataract and degeneration of the eye with retinal detachment.

- Facial: telecanthus (an increased distance between the corners of the eye), a median cleft of the upper lip and/or palatum, and a V-shaped hairline.

- Others: polydactyly (an excess of fingers or toes), syndactyly (fused fingers or toes), brachydactyly (short fingers and/or toes), clinodactyly (bending of the fifth fingers towards the fourth fingers), preauricular skin tags, an absent tragus, low set ears, deafness, small frontal sinuses, mental retardation, encephalocele (protrusion of the brain), spina bifida (split spine), meningoencephalocele (protrusion of both meninges), umbilical hernia, cryptorchidism (absence of one or two testes) and possibly cardiac anomalies.[6]

The clefts of the face that are present in FND are vertical clefts. These can differ in severity. When they are less severe, they often present with hypertelorism and normal brain development.[7] Mental retardation is more likely when the hypertelorism is more severe or when extracephalic anomalies occur.[8]

Classification

[9] There are multiple classification systems for FND. None of these classification systems have unraveled any genetic factors as the cause of FND. Yet, all of them are very valuable in determining the prognosis of an individual. In the subheadings below, the most common classifications will be explained.

Sedano classification

This is a classification based on the embryological cause of FND.

De Myer

This classification is based on the morphologic characteristics of FND, that describes a variety of phenotypes

Both of these classifications are further described in table 1. This table originates from the article ‘Acromelic frontonasal dysplasia: further delineation of a subtype with brain malformations and polydactyly (Toriello syndrome)', Verloes et al.

| Table 1. Phenotypic Classifications of the face in Frontonasal Dysplasia. | |||

| DeMyer classification (slightly expanded) | Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | hypertelorism, cranium bifidum, median cleft nose, and cleft prolabium | ||

| Type 2 | hypertelorism, cranium bifidum, and cleft nose but intact prolabium and palate | ||

| Type 3 | hypertelorism, median cleft nose, and median cleft of notched lip | ||

| Type 4 | hypertelorism and median cleft nose | ||

| Each type may be then subdivided in: | |||

| Subtype a | the two sides of the cleft nose are set apart | ||

| Subtype b | the two sides of the nose remain continuous. The cleft of the nose involves the nasal septum and extends to the tip of the nose | ||

| Subtype c | the cleft does not reach the tip of the nose. hypertelorism is borderline | ||

| Sedano-Jirásek classification | Characteristics | ||

| Type A | hypertelorism, median nasal groove, and absent nasal tip | ||

| Type B | hypertelorism, median groove or cleft face, with or without lip or palate cleft | ||

| Type C | hypertelorism and notching of alae nasi | ||

| Type D | hypertelorism, median groove or cleft face, with or without lip or palate cleft and notching of alae nasi | ||

Types

Pai syndrome

The Pai Syndrome is a rare subtype of frontonasal dysplasia. It is a triad of developmental defects of the face, comprising midline cleft of the upper lip, nasal and facial skin polyps and central nervous system lipomas. When all the cases are compared, a difference in severity of the midline cleft of the upper lip can be seen. The mild form presents with just a gap between the upper teeth. The severe group presents with a complete cleft of the upper lip and alveolar ridge.[4]

Nervous system lipomas are rare congenital benign tumors of the central nervous system, mostly located in the medial line and especially in the corpus callosum. Generally, patients with these lipomas present with strokes. However, patients with the Pai syndrome don’t. That is why it is suggested that isolated nervous system lipomas have a different embryological origin than the lipomas present in the Pai syndrome. The treatment of CNS lipomas mainly consists of observation and follow up.[4]

Skin lipomas occur relatively often in the normal population. However, facial and nasal lipomas are rare, especially in childhood. However, the Pai syndrome often present with facial and nasal polyps.[10] These skin lipomas are benign, and are therefore more a cosmetic problem than a functional problem.

The skin lipomas can develop on different parts of the face. The most common place is the nose. Other common places are the forehead, the conjunctivae and the frenulum linguae. The amount of skin lipomas is not related to the severity of the midline clefting.[4]

Patients with the Pai syndrome have a normal neuropsychological development.

Until today there is no known cause for the Pai syndrome. The large variety in phenotypes make the Pai syndrome difficult to diagnose. Thus the incidence of Pai syndrome seems to be underestimated.[10]

Acromelic frontonasal dysplasia (AFND)

Acromelic frontonasal dysplasia is a rare subtype of FND. It has an autosomal recessive inheritance. Acromelic frontonasal dysplasia is associated with central nervous system malformations and limb defects including a clubfoot, an underdeveloped shin-bone, and preaxial polydactyly of the feet. Preaxial polydactyly is a condition in which there are too many toes on the side of the big toe.[11] The phenotype of AFND is severe: a type Ia DeMyer and a Sedano type D. In contrast to the other subtypes of FND, AFND has a relatively high frequency of underlying malformations of the brain.[12]

Frontorhiny

Frontorhiny is another subtype of FND. It consists of multiple characteristics. Patient are characterized by: hypertelorism, a wide nasal bridge, a split nasal tip, a broad columella (strip of skin running from the tip of the nose to the upper lip), widely separated narrow nostrils, a long philtrum (vertical groove on the upper lip) and two-sided nasal swellings.[7]

Frontorhiny is one of the two subtypes of FND where a genetic mutation has been determined. The mutation has an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. The syndrome is often seen in siblings and, most of the time, parents are carriers. See Genetics.[13]

Craniofrontonasal dysplasia

Craniofrontonasal dysplasia (CFND) is a rare type of FND with X linked inheritance. Multiple features are characteristic for CFND such as craniosynostosis of the coronal sutures (prematurely closed cranial sutures), dry frizzy curled hair, splitting of the nails and facial asymmetry.

There is a large variety in phenotype. Women present with a more severe phenotype than men. Females characteristically have FND, craniosynostosis and additional small malformations. Males are usually more mildly affected, presenting with only hypertelorism. The gene that causes CFND is called EFNB1 and is located on the X chromosome. A hypothesis for the more severe outcome in females is based on X-inactivation, which leads to mosaicism. As a result, patients have less functional cells, generating abnormal tissue boundaries, termed "cellular interference". This process almost never occurs in males, as they have less mutagenic material in their genes. EFBN1 also has an important function in males.[13] As the syndrome has an X-linked inheritance pattern, there is no man-to-man inheritance.[3][6]

See→ Craniofrontonasal dysplasia for more information

Oculoauriculofrontonasal syndrome

OAFNS is a combination of FND and oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum (OAVS).[14]

The diagnosis of OAVS is based on the following facial characteristics: microtia (underdeveloped external ear), preauricular tags, facial asymmetry, mandibular hypoplasia and epibulbar lipodermoids (benign tumor of the eye which consists of adipose and fibrous tissue). There still remains discussion about the classification and the minimal amount of characteristics. When someone presents with FND and the characteristics of OAVS, the diagnosis OAFNS may be made.[14]

As the incidence of OAFNS is unknown, there are probably a lot of children with mild phenotypes that aren’t being diagnosed as being OAFNS.[14]

The cause of OAFNS is unknown, but there are some theories about the genesis. Autosomal recessive inheritance is suggested because of a case with two affected siblings [15] and a case with consanguineous parents.[16] However, another study shows that it is more plausible that OAFNS is sporadic.[17] It is known that maternal diabetes plays a role in developing malformations of craniofacial structures and in OAVS. Therefore, it is suggested as a cause of OAFNS. Folate deficiency is also suggested as possible mechanism.[14]

Low-dose CT protocols should be considered in diagnosing children with OAFNS.[14]

Cause

Embryogenesis

Midline facial clefts are one of the symptoms in FND. These defects develop in the early stages of embryological development. This is around the 19th to 21st day of pregnancy. The cause of the defect is failure of the mesodermal migration. The mesoderm is one of the germ layers (a collection of cells that have the same embryological origin). As a result of this failure, a midline facial cleft is formed.[4]

Another symptom of FND is the V-shaped hairline. In the normal situation, hair growth surrounding the eyes is inhibited. However, in FND this suppression is prevented in the midline by the increased inter-ocular distance. This causes the so-called widow’s peak (a V-shaped hairline) in FND patients.[8][11]

Very early in embryogenesis, the face and neck develop. This development continues until adolescence. Organs develop out of primordia (tissue in its earliest recognizable stage of development). The developmental processes of the face and jaw structures originate from different primordia:

- Unpaired frontonasal process

- Paired nasomedial and nasolateral processes

- Paired maxillary processes and mandibular processes

The formation of the frontonasal process is the result of a complex signaling system which begins with the synthesis of retinoic acid (a vitamin A metabolite). This is needed to set up the facial ectodermal zone. This zone makes signaling molecules that stimulate the cell proliferation of the frontonasal process. A midfacial defect will occur if this signaling pathway is disrupted. It is suggested that the absence of this pathway will lead to the formation of a gap, and that when the pathway is working too hard, excessive tissue will be formed. FND consists of various nasal malformations that result from excessive tissue in the frontonasal process, which results in hypertelorism and a broad nasal bridge.

Between the 4th and 8th week of pregnancy, the nasomedial and maxillary processes will fuse to form the upper lip and jaw. A failure of the fusion between the maxillary and nasomedial processes results in a cleft lip. A median cleft lip is the result of a failed fusion between the two nasomedial processes.

The palate is formed between the 6th and 10th week of pregnancy. The primordia of the palate are the lateral palatine processes and median palatine processes. A failure of the fusion between the median and lateral palatine processes results in a cleft palate.[18]

Genetics

There is still some discussion on whether FND is sporadic or genetic. The majority of FND cases are sporadic. Yet, some studies describe families with multiple members with FND.[3][7] Gene mutations are likely to play an important role in the cause. Unfortunately, the genetic cause for most types of FND remains undetermined.

Frontorhiny

The cause of frontorhiny is a mutation in the ALX3 gene. ALX3 is essential for normal facial development. Different mutations can occur in the ALX3 gene, but they all lead to the same effect: severe or complete loss of protein functionality.[7] The ALX3 mutation never occurs in a person without frontorhiny.[19]

Acromelic frontonasal dysostosis

It is thought that acromelic frontonasal dysostosis occurs due to an abnormality in the Sonic Hedgehog (SSH) signaling pathway. This pathway plays an important role in developing the midline central nervous system/craniofrontofacial region and the limbs. Hence, it is plausible that an error in the SSH pathway causes acromelic frontonasal dysostosis, because this syndrome not only shows abnormalities in the midfacial region, but also in the limbs and CNS.[11]

Diagnostics

The main diagnostic tools for evaluating FND are X-rays and CT-scans of the skull. These tools could display any possible intracranial pathology in FND. For example, CT can be used to reveal widening of nasal bones. Diagnostics are mainly used before reconstructive surgery, for proper planning and preparation.[7]

Prenatally, various features of FND (such as hypertelorism) can be recognized using ultrasound techniques.[8] However, only three cases of FND have been diagnosed based on a prenatal ultrasound.[20]

Other conditions may also show symptoms of FND. For example, there are other syndromes that also represent with hypertelorism. Furthermore, disorders like an intracranial cyst can affect the frontonasal region, which can lead to symptoms similar to FND. Therefore, other options should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.[8]

Treatment

Because newborns can breathe only through their nose, the main goal of postnatal treatment is to establish a proper airway.[21] Primary surgical treatment of FND can already be performed at the age of 6 months, but most surgeons wait for the children to reach the age of 6 to 8 years. This decision is made because then the neurocranium and orbits have developed to 90% of their eventual form. Furthermore, the dental placement in the jaw has been finalized around this age.[21][22]

Facial bipartition with median faciotomy

To correct the rather prominent hypertelorism, wide nasal root and midline cleft in FND, a facial bipartition can be performed. This surgery is preferred to periorbital box-osteotomy because deformities are corrected with a better aesthetic result.[22]

During the operation, the orbits are disconnected from the skull and the base of the skull. However, they remain attached to the upper jaw. Part of the forehead in the centre of the face is removed (median faciotomy) in the process. Then, the orbits are rotated internally, to correct the hypertelorism. Often, a new nasal bone will have to be interpositioned, using a bone transplant.

Complications of this procedure are: bleeding, meningitis, cerebrospinal fluid leakage and blindness.[23]

Rhinoplasty

Structural nasal deformities are corrected during or shortly after the facial bipartition surgery. In this procedure, bone grafts are used to reconstruct the nasal bridge. However, a second procedure is often needed after the development of the nose has been finalized (at the age of 14 years or even later).

Secondary rhinoplasty is based mainly on a nasal augmentation, since it has been proven better to add tissue to the nose than to remove tissue. This is caused by the minimal capacity of contraction of the nasal skin after surgery.[24]

In rhinoplasty, the use of autografts (tissue from the same person as the surgery is performed on) is preferred. However, this is often made impossible by the relative damage done by previous surgery. In those cases, bone tissue from the skull or the ribs is used. However, this may give rise to serious complications such as fractures, resorption of the bone, or a flattened nasofacial angle.

To prevent these complications, an implant made out of alloplastic material could be considered. Implants take less surgery time, are limitlessly available and may have more favorable characteristics than autografts. However, possible risks are rejection, infection, migration of the implant, or unpredictable changes in the physical appearance in the long term.

At the age of skeletal maturity, orthognathic surgery may be needed because of the often hypoplastic maxilla. Skeletal maturity is usually reached around the age of 13 to 16. Orthognathic surgery engages in diagnosing and treating disorders of the face and teeth- and jaw position.[21]

References

- 1 2 Lenyoun EH, Lampert JA, Xipoleas GD, Taub PJ (2011) Salvage of calvarial bone graft using acellular dermal matrix in nasal reconstruction and secondary rhinoplasty for frontonasal dysplasia. J Craniofac Surg. 22(4):1378-82.

- ↑ Wu E, Vargevik K, Slavotinek AM (2007) Subtypes of frontonasal dysplasia are useful in determining clinical prognosis. Am J Med Genet A. 143A(24):3069-78.

- 1 2 3 Fryburg JS, Persing JA, Lin KY, Frontonasal dysplasia in two successive generations, Am J Med Genet. 1993 Jul 1;46(6):712-4

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vaccarella F, Pini Prato A, Fasciolo A, Pisano M, Carlini C, Seymandi PL (2008) Phenotypic variability of Pai syndrome: report of two patients and review of the literature. 37(11):1059-64.

- ↑ Fearon, JA et al. (2008) Rare Craniofacial Clefts: A surgical Classification. J Craniofac Surg. 19(1):110-2.

- 1 2 Dubey SP, Garap JP (2000) The syndrome of frontonasal dysplasia, spastic paraplegia, mental retardation and blindness: a case report with CT scan findings and review of literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 54(1):51-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pham NS, Rafii A, Liu J, Boyadjiev SA, Tollefson TT (2011) Clinical and genetic characterization of frontorhiny: report of 3 novel cases and discussion of the surgical management. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 13(6):415-20

- 1 2 3 4 Gaball CW, Yencha MW, Kosnik S (2005). "Frontonasal dysplasia". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 133 (4): 637–8. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2005.06.019.

- ↑ Verloes A, Gillerot Y, Walczak E, Van Maldergem L, Koulischer L (1992). "Acromelic frontonasal "dysplasia": further delineation of a subtype with brain malformation and polydactyly (Toriello syndrome)". Am J Med Genet. 42 (2): 180–3. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320420209.

- 1 2 Guion-Almeida ML, Mellado C, Beltrán C, Richieri-Costa A (2007) Pai syndrome: report of seven South American patients. 143A(24):3273-9.

- 1 2 3 Slaney SF, Goodman FR, Eilers-Walsman BL, Hall BD, Williams DK, Young ID, Hayward RD, Jones BM, Christianson AL, Winter RM (1999). "Acromelic frontonasal dysostosis". Am J Med Genet. 83 (2): 109–16. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990312)83:2<109::aid-ajmg6>3.3.co;2-#.

- ↑ Chen CP (2008). "Syndromes, disorders and maternal risk factors associated with neural tube defects (V)". Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 47 (3): 259–66. doi:10.1016/s1028-4559(08)60122-9.

- 1 2 Twigg SR, Babbs C, van den Elzen ME, Goriely A, Taylor S, McGowan SJ, Giannoulatou E, Lonie L, Ragoussis J, Sadighi Akha E, Knight SJ, Zechi-Ceide RM, Hoogeboom JA, Pober BR, Toriello HV, Wall SA, Rita Passos-Bueno M, Brunner HG, Mathijssen IM, Wilkie AO (2013), "Cellular interference in CFND: males mosaic for mutations in the X-linked EFNB1 gene are more severely affected than true hemizygotes", Human Molecular Genetics, 22 (8): 1654–1662, PMC 3605834

, PMID 23335590, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt015

, PMID 23335590, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt015 - 1 2 3 4 5 Evans KN (2013). "Oculoauriculofrontonasal syndrome: case series revealing new bony nasal anomalies in an old syndrome". Am J Med Genet A. 161 (6): 1345–53. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35926.

- ↑ Golabi M, Gonalez MC, Edwards MS (1983). "A new syndrome of oculoauriculovertebral dyspasia and midline craniofacial defect: the oculoauriculofrontonasal syndrome: Two new cases in sibs". Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 19: 183–184.

- ↑ Guion-Almeida ML, Richieri-Costa A (2006). "Frontonasal malformation, first branchial arch anomalies, congenital heart defect, and severe central nervous system involvement: a possible "new" autosomal recessive syndrome?". Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 140 (22): 2478–81. PMID 17041938. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31518.

- ↑ Gabbett MT, Robertson SP, Broadbent R, Aftimos S, Sachdev R, Nezarati MM (2008). "Characterizing the oculoauriculofrontonasal syndrome". Clinical Dysmorphology. 17 (2): 79–85. doi:10.1097/mcd.0b013e3282f449c8.

- 1 2 Burce M. Carlson (2008). Human embryology and developmental biology, 4th edition. Mosby Elsevier. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-323-05385-3.

- ↑ Twigg SR, Versnel SL, Nürnberg G, Lees MM, Bhat M, Hammond P, Hennekam RC, Hoogeboom AJ, Hurst JA, Johnson D, Robinson AA, Scambler PJ, Gerrelli D, Nürnberg P, Mathijssen IM, Wilkie AO (2009). "Frontorhiny, a distinctive presentation of frontonasal dysplasia caused by recessive mutations in the ALX3 homeobox gene". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84 (5): 698–705. PMC 2681074

. PMID 19409524. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.009.

. PMID 19409524. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.009. - ↑ Martinelli P, Russo R, Agangi A, Paladini D. Prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of frontonasal dysplasia. Prenat Diagn (2002) 22(5):375-9.

- 1 2 3 Posnick JC, Seagle MB, Armstrong D (1990). "Nasal reconstruction with full-thickness cranial bone grafts and rigid internal skeleton fixation through a coronal incision". Plast Reconstr Surg. 86: 894–902. doi:10.1097/00006534-199011000-00010.

- 1 2 Kawamoto HK, Heller JB, Heller MM (2007). "Craniofrontonasal dysplasia: a surgical treatment algorithm". Plast Reconstr Surg. 120: 1943–1956. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000287286.12944.9f.

- ↑ Hayward R, Barry J. Thew clinical management of craniosynostosis. ISBN 1898683360

- ↑ Gryskiewicz JM, Rohrich RJ, Reagan BJ (2001). "Craniofrontonasal dysplasia: a surgical treatment algorithm". Plast Reconstr Surg. 107: 561–570.