Frisian freedom

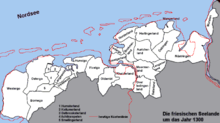

Friese freedom or freedom of the Frisians (West Frisian Fryske frijheid, Dutch: Friese Vrijheid) was the absence of feudalism and serfdom in Frisia, the area that was originally inhabited by the Frisians. Historical Frisia included the modern provinces of Friesland and Groningen, and the area of West Friesland, in the Netherlands, and East Friesland in Germany. During the period of Frisian freedom the area did not have a sovereign lord who owned and administered the land. The freedom of the Frisians developed in the context of ongoing disputes over the rights of local nobility.

Origin

When, around 800, the Scandinavian Vikings first attacked Frisia, which was still under Carolingian rule, the Frisians were released from military service on foreign territory in order to be able to defend themselves against the heathen Vikings. With their victory in the Battle of Norditi in 884 they were able to drive the Vikings permanently out of East Frisia, although it remained under constant threat. Over the centuries, whilst feudal lords reigned in the rest of Europe, no aristocratic structures emerged in Frisia. This 'freedom' was represented abroad by redjeven who were elected from among the wealthier farmers or from elected representatives of the autonomous rural municipalities. Originally the redjeven were all judges, so-called Asega, who were appointed by the territorial lords.[1]

The killing of Arnulf, Count of Holland in 993 is the first sign of the Frisian freedom. This Frisian count was killed in a rebel attempt to compel obedience from his subjects. The murder of another Count Henri de Gras in 1101 is regarded as the de facto beginning of the Frisian freedom. This freedom was recognized by the Holy Roman Emperor William II on November 3, 1248. He did this after the Frisians aided in the siege of the city of Aachen. In 1417 the status of the Frisians was reaffirmed by Emperor Sigismund. Later, Emperor Louis IV repealed these rights and granted Friesland to the Count of Holland.

An alternative interpretation of the origins of the freedom states that it was granted in the Karelsprivilege by Charlemagne to Magnus Forteman, as a reward for the conquest of Rome. Various sources have reported the existence of the Karelsprivilege or Magnuskerren. The original has been lost, although according to some it was inscribed on a wall of a church, which could be either at Almenum, Ferwâld or Aldeboarn. In 1319, more than five hundred years after the death of Charlemagne, a copy was entered in the register of William III of Holland. Some historians consider the Karelsprivilege an invention from subsequent times and believe that all copies that have been found are forgeries.

Regardless of the origins of the Frisian freedom, from the tenth century to the beginning of the sixteenth century Frisia went through a unique period of development, almost entirely lacking the feudal structure introduced by Charlemagne.

Content

The absence of a manorial authority meant that there existed no central administration. It also lacked any central legal or judicial system. In order to provide a systematic legal system, local leaders attempted to agree and apply rules to the entire region of Frisia. Legal and political delegates from various regions came to meetings at the Opstalboom in Aurich. Later those meetings were also held in Groningen.

In addition to the arrangements of the Opstalboom an attempt was tried to resort to the old law as it was recorded in the 17 and 24 Landrechten Keuren (landrights bylaws) Lex Frisionum. Even after a uniform legal system had been agreed on, the region's lack of central administration meant that there was no way to clarify the content of the law, and the enforcement of the law was left up to individual communities.

Friesland had no Knighthood or Ridderschap. In Friesland, the feudal idea of nobility, which gave the right of control in the country, was deemed incompatible with the "Frisian freedom". The region also had no forced labour. Some "nobles" still had a major influence in the region due to their great land ownership. The right to vote in local matters was based on the ownership of land, in which a person owning one unit of land received the right to have one vote. This meant that men owning large areas of land could cast more votes. Voting men used their influence to choose a mayor from one of the thirty municipalities, who in turn represented all of Friesland. Each city had eleven votes.

End

Duke Albrecht III of Saxony

The conflicts between the Schieringers and Vetkopers contributed in a significant way to the end of the Frisian Freedom. The absence of an effective authority also contributed to the emergence of disputes.

The arguments made it attractive for outsiders to interfere in their dealing with Friesland, sometimes with an appeal to old rights. At the same time triggered by the lawlessness which resulted from this battle, was the call for a lord. At the time in Friesland the Schieringer Potestaat Juw Dekama called upon the help of Albert, Duke of Saxony. This period is described by Petrus Thaborita.

The Frisian freedom disappeared in the other Frisian areas at different times. In West Friesland the freedom ended earlier with the conquest by the counts of Holland.

In the Frisian region in Groningen, the power vacuum in the course of the 14th and 15th centuries was filled by the city of Groningen. The city agreed various treaties with its environs, which was for the establishment of a court which had jurisdiction to rule and to take appeals. By the power of the city it was also able to fulfill these statements to monitor. The city was also presented as a strongly Frisian town, and as a champion of the Frisian Freedom.

After seeing the power of Albert of Saxony in Friesland, the city was forced to seek aid from a foreign noble. After a short period in which Charles, Duke of Guelders was finally adopted as Lord, Charles V annexed the city and its region to his empire. Charles appealed to the old rights of the bishop of Utrecht.

In East Friesland the Frisian Freedom ended in the mid-fifteenth century with the rise of the house of Cirksena.

See also

Bibliography

- O. Vries, Het Heilige Roomse Rijk en de Friese Vrijheid (The Holy Roman Empire and the Frisian Freedom) (Leeuwarden 1986)

- MP van Buijtenen, De grondslag van de Friese vrijheid (The basis of the Frisian freedom) (Assen 1953).

References

- ↑ Heinrich Schmidt: Politische Geschichte Ostfrieslands. 1975, p. 22 ff.