Friendship

Friendship is a relationship of mutual affection between people.[1] Friendship is a stronger form of interpersonal bond than an association. Friendship has been studied in academic fields such as communication, sociology, social psychology, anthropology, and philosophy. Various academic theories of friendship have been proposed, including social exchange theory, equity theory, relational dialectics, and attachment styles. A World Happiness Database study found that people with close friendships are happier.[2]

Although there are many forms of friendship, some of which may vary from place to place, certain characteristics are present in many types of bond. Such characteristics include affection; kindness; love; virtue; sympathy; empathy; honesty; altruism; mutual understanding and compassion; enjoyment of each other's company; trust; and the ability to be oneself, express one's feelings, and make mistakes without fear of judgment from the friend.

While there is no practical limit on what types of people can form a friendship, friends tend to share common backgrounds, occupations, or interests and have similar demographics.

Developmental psychology

In the typical sequence of an individual's emotional development, friendships are formed after parental bonding and before pair bonding. In the intervening period between the end of early childhood and the onset of full adulthood, friendships are often the most important relationships in the emotional life of the adolescent, and are often more intense than relationships later in life.[3] The absence of friends can be emotionally damaging.[4]

The evolutionary psychology approach to human development has led to the theory of Dunbar's number, proposed by British anthropologist Robin Dunbar. He theorized that there is a limit of approximately 150 people with whom a human can maintain stable social relationships.[5]

Childhood

In childhood, friendships are often based on the sharing of toys, and the enjoyment received from performing activities together. These friendships are maintained through affection, sharing, and creative playtime. While sharing is difficult for children at this age, they are more likely to share with someone they consider to be a friend [6][7] As children mature, they become less individualized and are more aware of others. They begin to see their friends' points of view, and enjoy playing in groups. They also experience peer rejection as they move through the middle childhood years. Establishing good friendships at a young age helps a child to be better acclimated in society later on in their life.[6] In a 1975 study,[8] Bigelow and La Gaipa found that expectations for a "best friend" become increasingly complex as a child gets older. The study investigated such criteria in a sample of 480 children between the ages of six and fourteen. Their findings highlighted three stages of development in friendship expectations. In the first stage, children emphasized shared activities and the importance of geographical closeness. In the second, they emphasized sharing, loyalty, and commitment. In the final stage, they increasingly desired similar attitudes, values, and interests. According to Berndt, children prize friendships that are high in pro-social behavior, intimacy, and other positive features; they are troubled by friendships that are high in conflict, dominance, rivalry, and other negative features. High-quality friendships have often been assumed to have positive effects on many aspects of children's social development. Perceived benefits from such friendships include enhanced social success, but they apparently do not include an effect on children's general self-esteem. Numerous studies with adults suggest that friendships and other supportive relationships do enhance self-esteem.[9] Other potential benefits of friendship include the opportunity to learn about empathy and problem solving.[10] Coaching from parents can be useful in helping children to make friends. Eileen Kennedy-Moore describes three key ingredients of children's friendship formation: (1) openness, (2) similarity, and (3) shared fun.[11][12][13] Parents can also help children understand social guidelines they haven't learned on their own.[14] Drawing from research by Robert Selman[15] and others, Kennedy-Moore outlines developmental stages in children's friendship, reflecting an increasing capacity to understand others' perspectives: "I Want It My Way", "What's In It For Me?", "By the Rules", "Caring and Sharing", and "Friends Through Thick and Thin."[16]

Adolescence

A study performed at the University of Texas at Austin examined over 9,000 American adolescents to determine how their engagement in problematic behavior (such as stealing, fighting, and truancy) was related to their friendships. Findings indicated that adolescents were less likely to engage in problem behavior when their friends did well in school, participated in school activities, avoided drinking, and had good mental health. The opposite was found regarding adolescents who did engage in problematic behavior. Whether adolescents were influenced by their friends to engage in problem behavior depended on how much they were exposed to those friends, and whether they and their friendship groups "fit in" at school.[17]

A study by researchers from Purdue University found that friendships formed during post-secondary education last longer than friendships formed earlier.[18]

Adulthood

Life events such as changes in marital status (marriage, divorce, widowhood), changes in parenthood (new parent, empty-nester), residential moves and career changes (new jobs, virtual employment, retirement) to name a few of the life events, can impact the quality or quantity of friendships. It is due to these changes, that many adults find that they have fewer friends than they had in younger years. And many adults feel that forming new friendships as an adult is difficult for all of these reasons too. After marriage, both women and men report having fewer friends of the opposite sex (Friendships, 2012).

Adults may find it particularly difficult to maintain meaningful friendships in the workplace. "The workplace can crackle with competition, so people learn to hide vulnerabilities and quirks from colleagues. Work friendships often take on a transactional feel; it is difficult to say where networking ends and real friendship begins."[19] Most adults value the financial security of their jobs more than friendship with coworkers.[20]

The majority of adults have an average of two close friends.[21]

Old age

As family responsibilities and vocational pressures become less, friendships become more important.[22] Among the elderly, friendships can provide links to the larger community; especially for people who cannot go out as often, interactions with friends allow for continued societal interaction. Additionally, older adults in declining health who remain in contact with friends show improved psychological well-being.

Although older adults prefer familiar and established relationships over new ones, friendship formation can continue in old age. With age, elders report that the friends to whom they feel closest are fewer in number and live in the same community. They tend to choose friends whose age, sex, race, ethnicity, and values are like their own. Compared with younger people, fewer older people report other-sex friendships. Older women, in particular, have more secondary friends—people who are not intimates, but with whom they spend time occasionally, such as in groups that meet for lunch or bridge.

Life cycle

Formation

Three significant factors make the formation of a friendship possible:

- Proximity – nearness or having a place or places to interact

- Repeated, unplanned interactions

- A setting that encourages people to let their guard down and confide in each other.[23]

Dissolution

Friendships end for many different reasons. Sometimes friends move away from each other and the relationship wanes due to the distance. Digital technology has however made geographic distance less of an obstacle to maintaining a friendship. Sometimes divorce causes an end to friendships, as people drop one or both of the divorcing people. For young people, friendships may end as a result of acceptance into new social groups.[24]

Friendships may end by fading quietly away or may end suddenly. How and whether to talk about the end of a friendship is a matter of etiquette that depends on the circumstances.

Developmental issues

ADD and ADHD

Children with Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may not have difficulty forming friendships, though they may have a hard time keeping them, due to impulsive behavior and hyperactivity. Children with Attention deficit disorder (ADD) may not have as much trouble keeping and maintaining friendships, though inattentiveness may complicate the processes.

Parents of children with ADHD worry about their children's ability to form long-lasting friendships. According to Edelman, "Making and keeping friends requires 'hundreds' of skills – talking, listening, sharing, being empathetic, and so on. These skills do not come naturally to children with ADD". Difficulty listening to others also inhibits children with ADD or ADHD from forming good friendships. Children with these disorders can also drive away others by "blurting out unkind comments". Their disruptive behavior can become too distracting to classmates.[25]

Autism

Children with autism spectrum disorders usually have some difficulty forming friendships. Certain symptoms of autism can interfere with the formation of interpersonal relations, such as a preference for routine actions, resistance to change, obsession with particular interests or rituals, and a lack of typical social skills. Children with autism spectrum disorders have been found to be more likely to be close friends of one person, rather than having groups of friends. Additionally, they are more likely to be close friends of other children with some sort of a disability.[26] A sense of parental attachment aids in the quality of friendships in children with autism spectrum disorders; a sense of attachment with one's parents compensates for a lack of social skills that would usually inhibit friendships.[27]

With time, moderation, and proper instruction, children with autism spectrum disorder are able to form friendships after realizing their own strengths and weaknesses. A study done by Frankel et al. showed that parental intervention and instruction plays an important role in such children developing friendships.[28] Along with parental intervention, school professionals play an important role in teaching social skills and peer interaction. Paraprofessionals, specifically one-on-one aides and classroom aides, are often placed with children with autism spectrum disorders in order to facilitate friendships and guide the child in making and maintaining substantial friendships.[29]

Although lessons and training may help peers of children with autism, bullying is still a major concern in social situations. According to Anahad O'Connor of The New York Times, bullying is most likely to occur against autistic children who have the most potential to live independently, such as those with Asperger syndrome. Such children are more at risk because they have as many of the rituals and lack of social skills as children with full autism, but they are more likely to be mainstreamed in school, since they are on the higher-functioning end of the autism spectrum. Children on the autism spectrum have more difficulty picking up on social cues of when they are maliciously being made fun of, so they do not always know when they are being bullied.[30]

Down syndrome

Children with Down syndrome have a difficult time forming friendships. They experience a language delay causing them to have a hard time playing with children. Most children with Down Syndrome like to watch other students and will play alongside a friend but not with them mostly because they understand more than they can express. As they get into the preschool years, children with Down Syndrome will benefit from being in the classroom setting, surrounded by other children and not being so dependent on an aid. Children with this disability highly benefit from a variety of interactions with both adults and children. Getting them out and exploring different social situations the better for these children. While at school, getting the classroom to be an inclusive one can be difficult but after a while it will become more normal for the other students in the classroom. Keeping the child with Down Syndrome with students that seem to be a true friend to them is crucial for their social development.[31][32]

Health

Conventional wisdom suggests that good friendships enhance an individual's sense of happiness and overall well-being. Indeed, a number of studies have found that strong social supports improve a woman's prospects for good health and longevity. Conversely, loneliness and a lack of social supports have been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, viral infections, and cancer, as well as higher mortality rates overall. Two researchers have even termed friendship networks a "behavioral vaccine" that boosts both physical and mental health.[33]

While there is an impressive body of research linking friendship and health, the precise reasons for the connection remain unclear. Most of the studies in this area are large prospective studies that follow people over a period of time, and while there may be a correlation between the two variables (friendship and health status), researchers still do not know if there is a cause and effect relationship, such as the notion that good friendships actually improve health. A number of theories have attempted to explain this link. These theories have included that good friends encourage their friends to lead more healthy lifestyles; that good friends encourage their friends to seek help and access services when needed; that good friends enhance their friends' coping skills in dealing with illness and other health problems; and that good friends actually affect physiological pathways that are protective of health.[34]

Quality

In Diderot's Encyclopedie his definition offers an early modern conception of good friendship in the 18th century. He writes:

"Friendship is nothing other than the practice of maintaining a decent and pleasant commerce with someone. Is friendship no more than that? Friendship, it will be said, is not limited to those terms; it goes beyond those narrow boundaries. But those who make this observation do not consider that two people do not, without being friends, maintain a connection that has nothing incorrect about it and that gives them reciprocal pleasure. The commerce that we may have with men involves either the mind or the heart. The pure commerce of the mind is called acquaintance; the commerce in which the heart takes an interest because of the pleasure it derives from it is friendship. I see no idea more accurate and more suitable for explaining all that friendship is in itself and likewise all its properties."[35]

Friendship quality is important for a person's well-being. High quality friendships have good ways of resolving conflict, ultimately leading to stronger and healthier relationships. Good friendship has been called "life enhancing" (Helm, 2012). Engaging in activities with friends intensifies pleasure and happiness. The quality of friendships relates to happiness because friendship "provides a context where basic needs are satisfied" (Demir, 2010). Quality friendships lead an individual to feel more comfortable with his or her personal identity. Higher friendship quality directly contributes to self-esteem, self-confidence, and social development.[9] Other studies have suggested that children who have friendships of a high quality may be protected against the development of certain disorders, such as anxiety and depression.[36][37]

Cultural variations

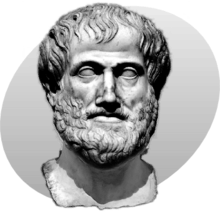

Ancient Greece

Friendship was a topic of moral philosophy greatly discussed by Plato, Aristotle, and Stoics. The topic was less discussed in the modern era, until the re-emergence of contextualist and feminist approaches to ethics.[38] In Ancient Greece, openness in friendship was seen as an enlargement of the self. Aristotle wrote, "The excellent person is related to his friend in the same way as he is related to himself, since, a friend is another self; and therefore, just as his own being is choiceworthy for him, the friend's being is choice-worthy for him in the same or a similar way."[39] In Ancient Greek, the same word ("philos") was used for "friend" and "lover".[40]

Central Asia

In Central Asia, male friendships tend to be reserved and respectful in nature. They may use nicknames and diminutive forms of their first names.

East Asia

The respect that friends have in East Asian culture is understood to be formed from a young age. Different forms of relationships in social media and online chats are not considered an official friendship in East Asian culture. Both female and male friendships in East Asia start at a younger age and grow stronger through years of schooling and working together. Different people in East Asian culture have a close, tight knit, group of friends that they call their "best friends." In the United States, many people refer to multiple people as their "best friends", as compared to East Asian culture, where best friends are the 2–3 people closest to a particular person. Being someone's best friend in East Asian culture is considered an honor and privilege. In a Chinese context, there is a very strong orientation towards maintaining and enhancing interpersonal relationships. The relationships between friends in East and Central Asian culture holds a tight bond that is usually never broken until someone geographically moves to another part of the country or out of the country.[41]

Germany

Germans typically have relatively few friends, although their friendships typically last a lifetime, as loyalty is held in high regard. German friendships provide a substantial amount of commitment and support. Germans may appear aloof to people from other countries, as they tend to be cautious and keep their distance when it comes to developing deeper relationships with new people. They draw a strong distinction between their few friends and their many associates, co-workers, neighbors, and others. A relationship's transition from one of associates to one of friends can take months or years, if it ever happens.[42]

Islamic cultures

In Islamic cultures, friendship is also known as companionship or ashab. The concept is taken seriously, and numerous important attributes of a worthwhile friend have emerged in Islamic media, such as the notion of a righteous (or saalih) person, who can appropriately delineate between that which is good and that which is evil. Concordance with the perspectives and knowledge of others is considered to be important; forgiveness regarding mistakes and loyalty between friends is emphasized, and a "love for the sake of Allah" is considered to be a relationship of the highest significance between two humans.[43]

Middle East

It is believed that in some parts of the Middle East (or Near East), friendship is more demanding when compared with other cultures; friends are people who respect each other, regardless of shortcomings, and will make personal sacrifices in order to assist another friend, without considering the experience an imposition.[44]

Many Arab people perceive friendship seriously, and deeply consider personal attributes such as social influence and the nature of a person's character before engaging in such a relationship.[44]

Russia

In Russia, friendship is defined as close relationship based on mutual trust, attachment and common interests.[45] The friendship typically assumes mutual help, understanding, frankness, emotional warmth, equality, unselfishness which is illustrated by an ample of traditional Russian proverbs.[46] For most Russians the term friendship is different from the business relationship because the latter does not have emotional attachment or unselfishness.

In the Soviet Union the collectivism has become the official moral stance, predominant political philosophy of the state. Principles of collectivism such as loyalty, tolerance and sacrifice have been postulated as a social norm. These collectivist principles have influenced the notion of friendship in Russia. Scarcity in the Soviet Union led people to create relationships with people in certain businesses in order to get the things they needed, such as a hospital employee to help obtain medical attention. This networking is recognised by Russians as advantageous acquaintance rather than the friendship because it lacks key friendship's elements.

Collectivism is no longer taken as a social norm in Russia. Youth in modern Russia are putting an emphasis on economic prosperity and individualism instead of collectivist principles.[47] However it does not mean a sudden redefinition of the term friendship. It rather means that business relations become more distinct from the conventional friendship today than in the past.

As in Germany, people in former Soviet republics had very few friends, but the friends they did have were extremely close. These trends have continued in modern Russia [48] Another trend within Russia is that many individuals are forced to constrain things in their lives, such as their friendships and their courses of study by using a cost-benefit approach. The young adults in Russia tend to use a more pragmatic approach in order to be successful in their studies as well as their work, which can affect friendships they may have.[49]

United States

In the United States, many types of relationships are deemed friendships. From the time children enter elementary school, many teachers and adults call their peers "friends" to children, and in most classrooms or social settings, children are instructed as to how to behave with their friends, and are told who their friends are (Stout 2010). This type of open approach to friendship has led many Americans, adolescents in particular, to designate a "best friend" with whom they are especially close (Stout 2010). Many psychologists see this term as dangerous for American children; because, it allows for discrimination and cliques, which can lead to bullying (Stout 2010).

For Americans, friends tend to be people whom they encounter fairly frequently, and that are similar to themselves in demographics, attitude, and activities.[48] While many other cultures value deep trust and meaning in their friendships, Americans will use the word "friend" to describe most people who have such qualities (Stout 2010). There is also a difference in the US between men and women who have friendships with the same sex. According to research, American men have less deep and meaningful friendships with other men. In the abstract, many men and women in the United States have similar definitions of intimacy, but women are more likely to practice intimacy in friendships.[50] Many studies have also found that Americans eventually lose touch with friends; this can be an unusual occurrence in many other cultures.[48]

According to a study documented in the June 2006 issue of the American Sociological Review, Americans are thought to be suffering a loss in the quality and quantity of close friendships since at least 1985.[51][52] The study states that one quarter of all Americans have no close confidants, and that the average total number of confidants per person has dropped from four to two.

Divorce also contributes to the decline in friendship among Americans. "In international comparisons, the divorce rate in the United States is higher than that of 34 other countries including the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia".[6] In divorce, many couples end up losing friends through the process, as certain friends "side with" one member of the relationship and lose the other.

The advance of technology has also been blamed for declining friendships in the United States. Ethan J. Leib, author of the book Friend vs. Friend and law professor at the University of California-Hastings, suggests that longer hours of work and a large amount of online communication take away from personal communication, making it harder to form friendships. Social media such as Facebook and Twitter have also led to a decrease in the amount of personal communication experienced in everyday life, and serves to make emotional attachments more difficult to achieve.[6] (Berry, 2012) (Freeman, 2011).

Paul Hollander wrote in Soviet and American Society (1973): In American society the term "friendship" is applied to relationships which in the Soviet Union (and much of Europe) would be called acquaintanceships. Many students and observers of American society, native and foreign alike, have suggested that the friendship of Americans tend to be superficial, short-lived, and limited in intimacy. Friendships in America do not often become lifelong exchanges of solidarity and moral and emotional support.

Aristotle's three kinds of friendship

Aristotle wrote extensively on the topic of friendship. In The Nicomachean Ethics he writes about his three different kinds of friendship that every individual goes through.

Kind one: friendship based on utility

“…the useful is not something that lasts, but varies with the moment; so, when what made them be friends has been removed, the friendship is dissolved as well, in so far as it existed in relation to what brought it about.[53]” Friendship of Utility is the kind of friendship where people use one another for a particular purpose. For example, you may have a grandparent who is always friendly towards the mailman. They may say hello or talk about the weather but when it is all said and done, there really is not a concrete relationship there. With that being said, this kind of friendship is typically seen amongst the elderly and middle-aged. “This sort don’t really even live together with each other, for sometimes they are not even pleasant people; and so neither do they feel an additional need for that kind of company, unless the people concerned are of some use, since they are pleasant just to the extent that they have hopes of some good accruing to them.”[54] This kind of friendship can be seen in those middle-aged people who are pursuing their own advantages in life. For example, one could have a colleague that they have to work with on a day-to-day basis. They may not even like this particular colleague but because they are a benefit to their success, they take advantage of that connection and they use it for their own good. “And in fact these friendships are friendships incidentally; for the one loved is not loved by reference to the person he is but to the fact that in the one case he provides some good and in the other some pleasure. Such friendships, then, are easily dissolved, if the parties become different; for if they are no longer pleasant or useful, they cease loving each other.”[55] Aristotle views this type of friendship as unstable and constantly subject to abrupt change.

Kind two: friendship based on pleasure

“Friendship between young people seems to be because of pleasure, since the young live by emotion, and more than anything pursue what is pleasant for them and what is there in front of them; but as their age changes, the things they find pleasant also become different.”[56] Friendship based on pleasure is that of passion between lovers and/or that of the like minded. In the minds of young people, they want someone who is pleasant to them. Unfortunately, due to the constant changes in the minds of the youth, these types of friendships don’t tend to be long lasting. “This is why they are quick to become friends and to stop being friends; for the friendship changes along with what is pleasant for them, and the shift in that sort of pleasure is quick.”[57] Now, this type of friendship can be confused with friendship based on utility but keep in mind that it is very different. First, the age groups are different being that utility friendships are for middle-aged to elderly people. Secondly, friendships of utility are typically based on something like a business deal where there is long term benefit. Friendship of pleasure is geared towards the feeling of passion and pleasure in regards to the way the friendship makes the person feel. “The young are also erotically inclined, for erotic is for the larger part a matter of emotion, and because of pleasure; hence they love and quickly stop loving, often changing in the course of the same day.”[58]

Kind three: friendship based on good

"And to those who wish good things for their friends, for their friends' sake, are friends most of all; for they do so because of the friends themselves, and not incidentally. So friendship between these lasts so long as they are good, and excellence is something lasting."[59] These types of friendships are long lasting because they involve all of the forms of friendship. Each person who has a friendship based on good has a mutual liking for the other person, they want good and pleasurable things from that person, and they know that that person will be there for them through the good and the bad. This kind of friendship is when a person wishes the best for the other person regardless of the other two forms. "For every kind of friendship is because of some good or because of pleasure, either without qualification or for the person loving, and in virtue of some sort of resemblance between the parties; and to this kind of friendship belong all the attributes mentioned, in virtue of what the friends are in themselves, since in this respect they are similar, and in the others, and the good without qualification is also pleasant without qualification--and these most of all are objects of love."[60] Though this kind of friendship is the "realest" of the three kinds, it is also hard to obtain. Both people in the friendship have to grow to really know one another. They have to go through the hard times and the good times with one another while in time, they have to develop a mutual trust and love for one another. "...for as the proverb has it, people cannot have got to know each other before they have savoured all that salt together, nor indeed can they have accepted each other or be friends before each party is seen to be lovable, and is trusted, by the other."[61]

Types

- Agentic friendship

- In an agentic friendship, both parties look to each other for help in achieving practical goals in their personal and professional lives.[62] Agentic friends may help with completing projects, studying for an exam, or with moving a friend from dwelling to dwelling. They value sharing time together, but only when they have time available to help each other. These relationships typically do not include the sharing of emotions or personal information.

- Best friend (or close friend)

- Best friends share extremely strong interpersonal ties with each other.

- Blood brother or sister

- This term can either refer to people related by birth or to friends who swear loyalty by mixing their blood together. The latter usage has been practiced throughout history, but is rarely continued today due to the dangers of blood-borne diseases.

- Boston marriage

- This antiquated American term was used during the 19th and 20th centuries to denote two women who lived together in the same household independent of male support. These relationships were not necessarily sexual. The term was used to quell fears of lesbians after World War I.

- Bromance

- A portmanteau of bro and romance, a bromance is a close, non-sexual relationship between two or more men.

- Womance

- A portmanteau of woman and romance, a womance is a close, non-sexual relationship between two or more women.

- Buddy

- Sometimes used as a synonym for friend generally, "buddy" can specifically denote a friend or partner with whom one engages in a particular activity, such as a "study buddy."

- Casual relationship or "friends with benefits"

- Also referred to as a "hook-up," this term denotes a sexual or near-sexual relationship between two people who do not expect or demand to share a formal romantic relationship.

- Communal friendship

- As defined by Steven McCornack, this is a friendship in which friends gather often to provide encouragement and emotional support in times of great need. This type of friendship tends to last only when the involved parties fulfill the expectations of support.[62]

- Comrade

- This term denotes an ally, friend, or colleague, especially in a military or political context. Comradeship may arise in time of war, or when people have a mutual enemy or even a common goal, in circumstances where ordinary friendships might not have formed.[63] In English, the term is associated with the Soviet Union, in which the Russian equivalent term, tovarishch (Russian: това́рищ), was used as a common form of address.

- Family friend

- This term can denote the friend of a family member or the family member of a friend.

- Frenemy

- A portmanteau of the words "friend" and "enemy," the term "frenemy" refers to either an enemy disguised as a friend (a proverbial wolf in sheep's clothing) or a person who is both a friend and a rival. This may take the form of a love–hate relationship. The term was reportedly coined by a sister of author and journalist Jessica Mitford in 1977 and popularized more than twenty years later on the third season of Sex and the City. One study by psychologist Julianne Holt-Lunstad found that unpredictable love–hate relationships can lead to elevations in blood pressure. In a previous study, the same researcher found that blood pressure is higher around people for whom one has mixed feelings than it is around people whom one clearly dislikes.

- Imaginary friend

- An imaginary friend is a non-physical friend, usually of a child. These friends may be human or animal, such as the human-sized rabbit in the 1950 Jimmy Stewart film Harvey. Creation of an imaginary friend may be seen as bad behavior or even taboo, but is most commonly regarded as harmless, typical childhood behavior.[64]

- Internet relationship

- An internet friendship is a form of friendship or romance which takes place exclusively over the internet. This may evolve into a real-life friendship. Internet friendships are in similar context to pen pals. People in these friendships may not use their true identities; parties in an internet relationship may engage in catfishing.

- Mate

- Primarily used in the UK, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand, "mate" is a same-sex friend, especially among males. In the UK, as well as Australia, the term also has been taken up by women.

- Cross-sex friendship

- Cross-sex friendships, which are nonsexual, are not always socially accepted. Although complications can arise in such relationships, cross-sex friendships can be strong and emotionally rewarding.[65][66]

- Pen pal

- Pen pals are people who have a relationship primarily through mail correspondence. They may or may not have met each other in person. This type of correspondence was encouraged in many elementary school children; it was thought that an outside source of information or a different person's experience would help the child become less insular. In modern times, internet relationships have largely replaced pen pals, though the practice does continue.

In animals

Friendship is also found among animals of higher intelligence, such as higher mammals and some birds. Cross-species friendships are common between humans and domestic animals. Cross-species friendships may also occur between two non-human animals, such as dogs and cats.

A study conducted by Krista McLennan, a doctoral student at Northampton University, investigated friendship in cows. McLennan measured the heart rates of cattle on three separate occasions to determine their stress levels. In the first trial, the cows were isolated from the rest of their herd. The second trial penned the animal with another cow that they were familiar with. Finally, the third trial put two random cows together. Her research showed that the cows were much more stressed when alone or with an unfamiliar cow than they were with one of their friends. This supports the idea that cows are social animals, capable of forming close bonds with each other. McLennan suggests that if farmers group friends together, it could benefit the cows by reducing their stress, improving their overall health and even producing a greater milk yield.[67]

See also

- Female bonding - The development of friendships between women

- Fraternization

- Friend of a friend

- Intimate relationship

- Male bonding

- Platonic love

- Social network - The architecture of friendship

- The Four Loves

References

- ↑ "Definition for friend". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford Dictionary Press. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ "Can we make ourselves happier?". BBC News. 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Conger, John Janeway; Galambos, Nancy (1997). Adolescence and youth: psychological development in a changing world (5th ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-673-99262-8.

- ↑ Grabmeier, Jeff (January 6, 2004). Friendships play key role in suicidal thoughts of girls, but not boys. Ohio State University.

- ↑ Dunbar, R.I.M. (1992). "Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates". Journal of Human Evolution. 22: 469–493. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(92)90081-j.

- 1 2 3 4 Newman, B. M. & Newman, P.R. (2012). Development Through Life: A Psychosocial Approach. Stanford, CT.

- ↑ "Your Childhood Friendships Are The Best Friendships You’ll Ever Have". 17 Jun 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ Cited in Brace, N. & Byford, J. (Ed.) (2010) Discovering psychology: What is friendship. The Open university. ISBN 1-84873-466-2.

- 1 2 Berndt, T. J. (2002). Friendship Quality and Social Development. American Psychological Society. Purdue University.

- ↑ Kennedy-Moore, E. (2013). "What Friends Teach Children".

- ↑ Kennedy-Moore, E. (2012). "How children make friends (part 1)".

- ↑ Kennedy-Moore, E. (2012). "How children make friends (part 2)".

- ↑ Kennedy-Moore, E. (2012). "How children make friends (part 3)".

- ↑ Elman, N. M. & Kennedy-Moore, E. (2003). The Unwritten Rules of Friendship: Simple Strategies to Help Your Child Make Friends. New York: Little, Brown.

- ↑ Selman, R. L. (1980). The Growth of Interpersonal Understanding: Developmental and Clinical Analyses. Academic Press: New York.

- ↑ Kennedy-Moore, E. (2012). "Children's Growing Friendships".

- ↑ Crosnoe, R., & Needham, B. (2004) Holism, contextual variability, and the study of friendships in adolescent development. University of Texas at Austin.

- ↑ Sparks, Glenn (August 7, 2007). Study shows what makes college buddies lifelong friends. Purdue University.

- ↑ Williams, Alex (13 July 2012). "Friends of a Certain Age: Why Is It Hard To Make Friends Over 30?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ↑ Bryant, Susan. "Workplace Friendships: Asset or Liability?". Monster.com. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ↑ Willis, Amy (November 8, 2011). "Most adults have 'only two close friends'". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ↑ Laura E. Berk (2014). Pearson - Exploring Lifespan Development, 3/E. p. 696. ISBN 9780205957385.

- ↑ Williams, Alex (15 July 2012). "Why Is It Hard to Make Friends Over 30?". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ↑ Friendships, 2009; Berry, 2012.

- ↑ Edelman, Gay. "Why ADHD Children Have a Hard Time Making Friends". National Children's Museum. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ↑ Bauminger, Nirit; Solomon, Marjorie; Aviezer, Anat; Heung, Kelly; Gazit, Lilach; Brown, John; Rogers, Sally J. (3 January 2008). "Children with Autism and Their Friends: A Multidimensional Study of Friendship in High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 36 (2): 135–150. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9156-x.

- ↑ Bauminger, Nirit; Solomon, Marjorie; Rogers, Sally J. (29 December 2009). "Predicting Friendship Quality in Autism Spectrum Disorders and Typical Development". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 40 (6): 751–761. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0928-8.

- ↑ Frankel, Fred; Myatt, Robert; Sugar, Catherine; Whitham, Cynthia; Gorospe, Clarissa M.; Laugeson, Elizabeth (8 January 2010). "A Randomized Controlled Study of Parent-assisted Children's Friendship Training with Children having Autism Spectrum Disorders". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 40 (7): 827–842. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0932-z.

- ↑ Rossetti, Zachary; Goessling, Deborah (July–August 2010). "Paraeducators' Roles in Facilitating Friendships Between Secondary Students With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorders or Developmental Disabilities". Teaching Exceptional Children. 6. 42: 64–70.

- ↑ O'Connor, Anahad (3 September 2012). "School Bullies Prey on Children With Autism". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Recreation & Friendship." Recreation & Friendship - National Down Syndrome Society. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.

- ↑ "Social Development for Individuals with Down Syndrome - An Overview." Information about Down Syndrome. Down Syndrome Education International, n.d. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.

- ↑ Friendship, social support, and health. 2007 Sias, Patricia M; Bartoo, Heidi. In L'Abate, Luciano. Low-cost approaches to promote physical and mental health: Theory, research, and practice. (pp. 455–472). xxii, 526 pp. New York, NY, US: Springer Science + Business Media.

- ↑ Social networks and health: It's time for an intervention trial. 2005. Jorm, Anthony F. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. Vol 59(7) Jul 2005, 537–538.

- ↑ "Friendship". quod.lib.umich.edu.

- ↑ Brendgen, M.; Vitaro, F.; Bukowski, W. M.; Dionne, G.; Tremblay, R. E.; Boivin, M. (2013). "Can friends protect genetically vulnerable children from depression?". Development and Psychopathology. 25: 277–289. doi:10.1017/s0954579412001058.

- ↑ Bukowski, W. M.; Hoza, B.; Boivin, M. (1994). "Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: the development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 11: 471–484. doi:10.1177/0265407594113011.

- ↑ Lucas, Chris. "Contextual Ethics". Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Owen, Terence (1996). Aristotle: Introductory Readings. Hackett. p. 274.

- ↑ Tokar, Alexander (2009). Metaphors of the Web 2.0: with special emphasis on social networks and folksonomies. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. p. 57. ISBN 3631586647.

- ↑ Said, Edward (1979). Orientalism. United States: Vintage Books. p. Chapter 2: Orientalist Structures and Restructures. ISBN 978-0-394-74067-6. ISBN 0-394-74067-X.

- ↑ Nees, Greg (2000). Germany: Unraveling an Enigma. Intercultural Press. pp. 66–68. ISBN 9781877864759.

- ↑ Br. Isa Al-Bosnee. "Islam & the Concept of Friendship". Mission Islam. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- 1 2 Radwan, Nouran. "Arab Friendship". Fact of Arabs. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ↑ "дружба, что такое дружба - С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова Толковый словарь русского языка". www.classes.ru. Retrieved 2016-12-28.

- ↑ "Пословицы и поговорки о дружбе :: Родной язык - детям". allforchildren.ru. Retrieved 2016-12-28.

- ↑ Vandegrift, Darcie (24 July 2015). "'We don't have any limits': Russian young adult life narratives through a social generations lens". Journal of Youth Studies. 19: 221–236. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1059930.

- 1 2 3 Sheets, V. L. & Lugar, R. (November 2005). Sources of Conflict Between Friends in Russia and the United States. Cross-Cultural Research November 2005 39: 380-398.

- ↑ Vandegrift, Darcie (2015-07-24). "'We don't have any limits': Russian young adult life narratives through a social generation lens". Journal of Youth Studies. 19: 221–236. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1059930.

- ↑ Yugar, J. M. & Shapiro, E.S. (2001). Elementary Children's School Friendship: A Comparison of Peer Assessment Methodologies. School Psychology Review, Vol. 30, No. 4

- ↑ Kornblum, Janet (June 22, 2006). Study: 25% of Americans have no one to confide in. USA Today.

- ↑ McPherson, Smith-Lovin, Brashears (Volume 71, Number 3, June 2006). Asanet.orgAmerican Sociological Review. Archived September 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 210 II56a11. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 211 II56a24–31. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 211 II56a17–20. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 211 II56a32–35. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 211 II56a35–37. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 211 II56b1–5. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 211 II56b10–12. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 212 II56b19–23. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- ↑ Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Christopher Rowe. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. 2002. pp. 212 II56b27–29. ISBN 0-19-875271-7.

- 1 2 McCornack, Steven. Reflect & Relate: An introduction to interpersonal communication. Boston: Bedford. pp. 383–384.

- ↑ Hedges, Chris (21 May 2003). "Text of the Rockford College graduation speech". Rockford Register Star. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ↑ Kennedy-Moore, E. (2013). "Imaginary friends".

- ↑ Kennedy-Moore, E. (2011). "Can boys and girls be friends".

- ↑ "Can Men and Women Be Friends?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "Heifer so lonely: How cows have best friends and get stressed when they are separated". Mail Online. London. 5 July 2011. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

Further reading

- Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics.

- Bray, Alan (2003). The Friend. United States: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226071817.

- Bleske, April L.; Buss, David M. (June 2000). "Can Men and Women Be Just Friends?". In Personal Relationships. 7 (2): 131–151. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2000.tb00008.x.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Laelius de Amicitia.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo (1841). "Friendship". Essays: First Series. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Garrison, John (2014). Friendship and Queer Theory in the Renaissance. United States: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415713221.

- Heyking, John von; Avramenko, Richard (2008). Friendship and Politics: Essays in Political Thought. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Hruschka, Daniel (2010). Friendship: Development, Ecology and Evolution of a Relationship. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Kalmijn, Matthijs (March 2002). "Sex Segregation of Friendship Networks: Individual and Structural Determinants of Having Cross-Sex Friends". European Sociological Review. 18 (1): 101–117. doi:10.1093/esr/18.1.101.

- Lepp, Ignace (1966). The Ways of Friendship. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Muraco, Anna (October 2005). "Heterosexual Evaluations of Hypothetical Friendship Behavior Based on Sex and Sexual Orientation". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 22 (5): 587–605. doi:10.1177/0265407505054525.

- Reeder, Heidi M. (August 2003). "The Effect of Gender Role Orientation on Same- and Cross-Sex Friendship Formation". Sex Roles: A Journal of Research. 49 (3–4): 143–152.

- Said, Edward (1979). Orientalism. United States: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-74067-X.

- Wilson, Amy (2012). Put the End in Friend: Ridding Your Life of People that Suck. New York: Kingery & Bailiff Enterprises, Chariton Press.

- Yager, Jan (2002). When Friendship Hurts: How to Deal With Friends Who Betray, Abandon, or Wound You. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc., Fireside Books.

External links

| Look up mate in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Friendship |

| Look up friendship in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Media related to Friends at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Friends at Wikimedia Commons- BBC Radio 4 series "In Our Time", on Friendship, 2 March 2006

- Friendship at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy