French battleship Démocratie

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Démocratie |

| Namesake: | Democracy |

| Laid down: | 1 May 1903 |

| Launched: | 30 April 1904 |

| Commissioned: | January 1908 |

| Struck: | 1921 |

| Fate: | Broken up for scrap |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Liberté-class pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 14,860 t (14,630 long tons; 16,380 short tons) |

| Length: | 133.81 m (439.0 ft) pp |

| Beam: | 24.26 m (79.6 ft) |

| Draft: | 8.41 m (27.6 ft) |

| Propulsion: | 3 triple-expansion steam engines, 18,500 shp (13,800 kW) |

| Speed: | 19 knots (35 km/h) |

| Complement: | 739–769 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

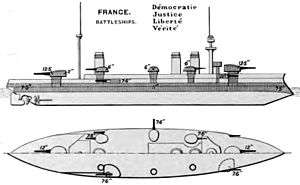

Démocratie was a pre-dreadnought battleship of the Liberté class built by the French Navy. She had three sister ships: Liberté, Justice, and Vérité. Démocratie was laid down in May 1903, launched in April 1904, and completed in January 1908, over a year after the revolutionary British battleship HMS Dreadnought made ships like Démocratie obsolete. She was armed with a main battery of four 305 mm (12.0 in) guns, compared to the ten guns of the same caliber mounted on Dreadnought.

Despite her out-dated design, Démocratie served with the French Mediterranean Fleet throughout her career, including during World War I. She participated in the Battle of Antivari in late August 1914, and spent the majority of the war based on the coast of Greece, in Corfu and Mudros, to keep the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman navies bottled up in port, though she saw no further action. After the end of the war, she went into the Black Sea to assist in the enforcement of the terms of the Armistice with Germany. Démocratie was stricken in 1921 and subsequently broken up for scrap.

Design

Démocratie was laid down at the Arsenal de Brest shipyard on 1 May 1903, launched on 30 April 1904, and completed in January 1908,[1] over a year after the revolutionary British battleship HMS Dreadnought, which rendered the pre-dreadnoughts like Démocratie outdated before they were completed.[2] The ship was 133.81 meters (439 ft 0 in) long between perpendiculars and had a beam of 24.26 m (79 ft 7 in) and a full-load draft of 8.41 m (27 ft 7 in). She displaced up to 14,489 metric tons (14,260 long tons; 15,971 short tons) at full load. Démocratie had a crew of between 739 and 769 officers and enlisted men. The ship's propulsion system consisted of three vertical triple expansion engines with twenty-two Belleville boilers. They were rated at 18,500 indicated horsepower (13,800 kW) and provided a top speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). Coal storage amounted to 1,800 t (1,800 long tons; 2,000 short tons).[1]

Démocratie's main battery consisted of four Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893/96 guns mounted in two twin gun turrets, one forward and one aft. The secondary battery consisted of ten 194 mm (7.6 in) guns; six were mounted in single turrets, and four in casemates in the hull. She also carried thirteen 65 mm (2.6 in) guns and ten 3-pounders, and had two 450 mm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes submerged in the hull. The ship's main belt was 280 mm (11.0 in) thick and the main battery was protected by up to 350 mm (13.8 in) of armor. The conning tower had 305 mm (12.0 in) thick sides.[1]

Service history

In August 1910, the 1st Squadron of the Mediterranean fleet conducted a gunnery practice using the old ironclad Fulminant as a target; Démocratie scored 22.7 percent hits, the second best performance in the squadron and surpassed only by her sister Justice.[3] During a fleet exercise on 28 May 1914, Démocratie collided with the battleship Suffren when the latter vessel lost power. Suffren was only lightly damaged, with her port anchor and hawsepipe carried away.[4]

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Démocratie was assigned to the 1st Division of the 2nd Squadron in the Mediterranean, along with Justice.[5] The French fleet was initially used to cover the movement of French troops—the XIX Corps—from Algeria to metropolitan France. As a result, the fleet was far out of position to catch the German battlecruiser SMS Goeben.[6] For the majority of the war, the French used their main fleet to keep the Austro-Hungarian fleet bottled up in the Adriatic Sea. In 1914 she participated in the Battle of Antivari, where the battle line caught the Austro-Hungarian cruiser SMS Zenta by surprise and sank her. The French battleships then bombarded Austrian fortifications at Cattaro in an attempt to draw out the Austro-Hungarian fleet, which refused to take the bait.[7]

The French operations in the area were hampered by a lack of a suitable base close to the mouth of the Adriatic; the British had given the French free access to Malta, but that was hundreds of miles away. The Austrians also possessed several submarines, one of which torpedoed the dreadnought Jean Bart in December 1914. This threat from underwater weapons greatly limited French naval activities in the Adriatic.[8] As the war progressed, the French eventually settled on Corfu as their primary naval base in the area.[9] Later in the war, Démocratie was sent to Mudros along with her sister ships to reinforce the blockade of the Dardanelles.[10]

Shortly after the end of the war, Démocratie, Justice, and a destroyer joined an Allied fleet (including the British dreadnoughts HMS Superb and Temeraire and the Italian battleship Roma) that was sent to the Black Sea port of Sevastopol. They oversaw the enforcement of the terms of the Armistice with Germany; the Germans had previously seized Russian naval units and stationed occupation forces there under the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.[11] The French contingent provided crews for a pair of Russian destroyers and two German U-boats, and the other Allied ships similarly activated Russian and German vessels to secure the area.[12] Démocratie ultimately was stricken from the naval register in 1921 and sold to ship-breakers.[1]

Footnotes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Démocratie (ship, 1904). |

References

- Alger, Philip R., ed. (1910). United States Naval Institute Proceedings. Annapolis, MD: US Naval Institute. 36. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Caresse, Philippe (2010). "The Drama of the Battleship Suffren". In Jordan, John. Warship 2010. London: Conway. pp. 9–26. ISBN 978-1-84486-110-1.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-8317-0302-8.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1922. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Guernsey, Irwin Scofield (1920). A Reference History of the War. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead & Co.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Halpern, Paul G. (2004). The Battle of the Otranto Straits. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34379-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (2011). The Mediterranean Fleet, 1919–1929. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 9781409427568.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I. New York, NY: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.