French battleship Charlemagne

Charlemagne at anchor | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Charlemagne |

| Namesake: | Charlemagne |

| Builder: | Arsenal de Brest |

| Laid down: | 2 August 1894 |

| Launched: | 17 October 1895 |

| Completed: | 12 September 1897 |

| Commissioned: | 15 September 1897 |

| Decommissioned: | 1 November 1917 |

| Struck: | 21 June 1920 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap, 1923 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Charlemagne-class battleship |

| Displacement: | 11,275 t (11,097 long tons) (deep load) |

| Length: | 117.7 m (386 ft 2 in) |

| Beam: | 20.3 m (66 ft 7 in) |

| Draught: | 8.4 m (27 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 3 shafts, 3 four-cylinder vertical triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range: | 4,200 miles (3,650 nmi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 727 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: |

|

Charlemagne was a pre-dreadnought battleship built for the French Navy in the mid-1890s, name ship of her class. She spent most of her career assigned to the Mediterranean Squadron (escadre de la Méditerranée). Twice she participated in the occupation of the port of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, then owned by the Ottoman Empire, once as part of a French expedition and another as part of an international squadron.

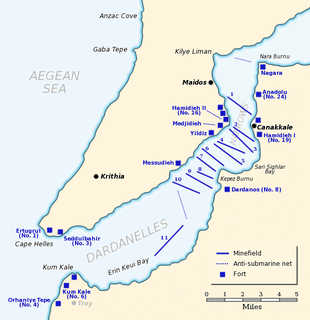

When World War I began in August 1914, she escorted Allied troop convoys for the first two months. Charlemagne was ordered to the Dardanelles in November 1914 to guard against a sortie into the Mediterranean by the German battlecruiser SMS Goeben. In 1915, she joined British ships in bombarding Turkish fortifications under the command of Rear Admiral (contre-amiral) Emile Guépratte. The ship was transferred later that year to the squadron assigned to prevent any interference by the Greeks with Allied operations on the Salonica front. Charlemagne was placed in reserve and then disarmed in late 1917. She was condemned in 1920 and later sold for scrap in 1923.

Design and description

Charlemagne was 117.7 metres (386 ft 2 in) long overall and had a beam of 20.3 metres (66 ft 7 in). At deep load, she had a draught of 7.4 metres (24 ft 3 in) forward and 8.4 metres (27 ft 7 in) aft. She displaced 11,275 metric tons (11,097 long tons) at deep load.[1] Her crew consisted of 727 officers and enlisted men.[2]

The ship used three 4-cylinder vertical triple expansion steam engines, one engine per shaft. Rated at 14,500 PS (10,700 kW), they produced 15,295 metric horsepower (11,249 kW) during the ship's sea trials using steam generated by 20 Belleville water-tube boilers. Charlemagne reached a top speed of 18.14 knots (33.60 km/h; 20.88 mph) on her trials. She carried a maximum of 1,050 tonnes (1,030 long tons) of coal which allowed her to steam for 4,200 miles (3,600 nmi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1]

Charlemagne carried her main armament of four 40-calibre Canon de 305 mm Modèle 1893 guns in two twin-gun turrets, one each fore and aft. The ship's secondary armament consisted of ten 45-calibre Canon de 138 mm Modèle 1893 guns, eight of which were mounted in individual casemates and the remaining pair in shielded mounts on the forecastle deck amidships. She also carried eight 45-calibre Canon de 100 mm Modèle 1893 guns in shielded mounts on the superstructure. The ship's anti-torpedo boat defences consisted of twenty 40-calibre Canon de 47 mm Modèle 1885 Hotchkiss guns, fitted in platforms on both masts, on the superstructure, and in casemates in the hull. Charlemagne mounted four 450-millimetre (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, two on each broadside. Two of these were submerged, angled 20° from the ship's axis, and the other two were above the waterline. They were provided with twelve Modèle 1892 torpedoes. As was common with ships of her generation, she was built with a plough-shaped ram.[3]

The Charlemagne-class ships carried a total of 820.7 tonnes (807.7 long tons)[4] of Harvey armour.[5] They had a complete waterline armour belt that was 3.26 metres (10 ft 8 in) high. The armour belt tapered from its maximum thickness of 400 mm (15.7 in) to a thickness of 110 mm (4.3 in) at its lower edge. The armoured deck was 55 mm (2.2 in) thick on the flat and was reinforced with an additional 35 mm (1.4 in) plate where it angled downwards to meet the armoured belt. The main turrets were protected by 320 mm (12.6 in) of armour and their roofs were 50 mm (2.0 in) thick. Their barbettes were 270 mm (10.6 in) thick. The outer walls of the casemates for the 138.6-millimetre (5.46 in) guns were 55 mm thick and they were protected by transverse bulkheads 150 mm (5.9 in) thick. The conning tower walls were 326 mm (12.8 in) thick and its roof consisted of 50 mm armour plates. Its communications tube was protected by armour plates 200 mm (7.9 in) thick.[4]

Construction and career

Charlemagne, named after the first Holy Roman Emperor,[2] was authorised on 30 September 1895 as the name ship of the three battleships of her class. The ship was laid down at the Arsenal de Brest on 2 August 1894[2] and launched on 17 October 1895. She was completed on 12 September 1897 and commissioned three days later.[1]

Charlemagne was initially assigned to the Northern Squadron (escadre du Nord), but, together with Gaulois, she was transferred to the 1st Battleship Division of the Mediterranean Squadron in January 1900. On 18 July, after combined manoeuvres with the Northern Squadron, the ship participated in a naval review conducted by the President of France, Émile Loubet, at Cherbourg. She escorted Louis André, the Minister of War and Jean de Lanessan, the Minister of Marine on their tours of Corsica and Tunisia later in October. The following year, Charlemagne and the Mediterranean Squadron participated in an international naval review by President Loubet in Toulon with ships from Spain, Italy and Russia.[6][7]

In October 1901, the 1st Battleship Division, under the command of Rear Admiral Leonce Caillard, was ordered to proceed to the port of Mytilene. After landing two companies of marines that occupied the major ports of the island on 7 November, Sultan Abdul Hamid II agreed to enforce contracts made with French companies and to repay loans made by French banks. The 1st Division departed Lesbos in early December and returned to Toulon.[8] In January–March 1902, Charlemagne was deployed in Moroccan waters and participated in the summer fleet exercises later that year.[7] Naval historians Paul Silverstone and Eric Gille claim that the ship collided with Gaulois on 2 March 1903, but was not damaged.[2][7][Note 1] In April 1904, she was one of the ships that escorted President Loubet during his state visit to Italy and participated in the annual fleet manoeuvers later that summer. A 100 mm cartridge spontaneously ignited in a magazine in January 1905, but Charlemagne suffered no damage from the incident.[7] Together with the destroyer Dard, the ship was the French contribution to an international squadron that briefly occupied Mytilene in November–December 1905 and participated in a naval review by President Armand Fallières in September of the following year.[10] She engaged in the summer naval manoeuvres in 1907 and 1908 and was transferred to the 4th division in September 1908.[11]

Charlemagne was transferred back to the Northern Squadron in October 1909. She made port visits to Oran, Cadiz, Lisbon and Quiberon before having her bottom cleaned in Brest in January 1910. The ship participated in a large naval review by President Fallières off Cap Brun on 4 September 1911. Charlemagne was placed in reserve in Brest in September 1912 for an overhaul; the ship rolled 34° during sea trials in May 1913, after completion of the overhaul. She was assigned to the training squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet from August 1913 until the beginning of World War I a year later.[12]

World War I

Together with the older French pre-dreadnoughts, Charlemagne escorted Allied troop convoys through the Mediterranean until November when she was ordered to the Dardanelles to guard against a sortie by the Goeben. During the bombardment on 25 February 1915, the ship engaged the fort at Kum Kale with some effect. On 18 March, Charlemagne, together with Bouvet, Suffren, and Gaulois, was to penetrate deep into the Dardanelles after six British battleships suppressed the defending Turkish fortifications and attack those same fortifications at close range. After the French ships were ordered to be relieved by six other British battleships,[13] Bouvet struck a mine and sank almost instantly while Gaulois was hit twice, one of which opened a large hole in her hull that began to flood the ship. Charlemagne escorted Gaulois to the Rabbit Islands, north of Tenedos, where the latter ship could be beached for temporary repairs.[14] Charlemagne herself was moderately damaged during the bombardment and continued onwards to Bizerte for repairs that lasted through May.[12]

Upon her return, she was assigned to the Dardanelles Squadron (escadre des Dardanelles), although naval operations were limited to bombarding Turkish positions in support of Allied troops by that time. The ship was transferred to Salonica in October 1915 where she joined the French squadron assigned to prevent any interference by the Greeks with Allied operations in Greece. Charlemagne was relieved for a major refit at Bizerte in May 1916 that lasted until August. She returned to Salonica later that month and was assigned to the Eastern Naval Division (division navale d'Orient). The ship remained there until she was ordered to Toulon in August 1917. Charlemagne was placed in reserve on 17 September and disarmed on 1 November. She was condemned on 21 June 1920[12] and later sold for scrap in 1923.[2]

Notes

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Gille, p. 98

- 1 2 3 4 5 Silverstone, p. 92

- ↑ Caresse, pp. 114, 116–17

- 1 2 Caresse, p. 117

- ↑ Chesneau and Kolesnik, p. 117

- ↑ Caresse, pp. 119–20

- 1 2 3 4 Gille, p. 96

- ↑ Caresse, p. 121

- ↑ Caresse, p. 122

- ↑ Lange-Akhund, p. 299

- ↑ Gille, pp. 96–97

- 1 2 3 Gille, p. 97

- ↑ Corbett, pp. 160, 214, 218

- ↑ Caresse, pp. 129–30

Bibliography

- Caresse, Phillippe (2012). "The Battleship Gaulois". In Jordan, John. Warship 2012. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-156-9.

- Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Corbett, Julian (1997). Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. II (reprint of the 1929 second ed.). London and Nashville, TN: Imperial War Museum in association with the Battery Press. ISBN 1-870423-74-7.

- Gille, Eric (1999). Cent ans de cuirassés français. Nantes: Marines. ISBN 2-909675-50-5.

- Lange-Akhund, Nadine (1998). The Macedonian Question, 1893-1908, from Western Sources. East European Monographs. CDLXXXVI. Boulder, Colorado: East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-383-9.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charlemagne. |

- (in French) CUIRASSE Charlemagne