French Grant

The French Grant (also known as the French-Grant Estates) was a land tract in the Northwest Territory, present day Scioto County, Ohio, that was paid out by the U.S. Congress on March 31, 1795.[1] This was after a group of French colonists were defrauded by the Scioto Company of purchased land grants which rightly were controlled by the Ohio Company of Associates. Not all of the settlers took the grant, some preferring to stay on the East Coast others preferring stay in Gallipolis, Ohio in Gallia County. (Gallia and Gallipolis were named for Gaul, the ancient Latin name of France.)

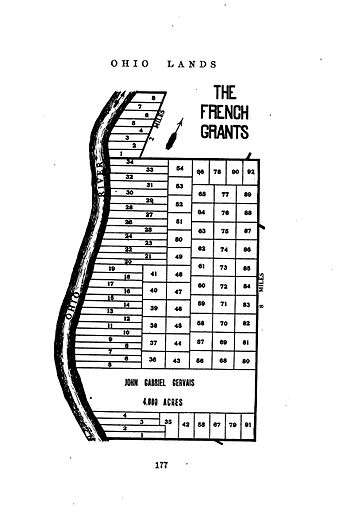

The First Grant extended from a point on the Ohio River 1.5 miles (2.4 km) above and opposite the mouth of Little Sandy River (Kentucky) in Kentucky, and extending eight miles (13 km) in a direct line down the river, and from the two extremities of that line, reaching back at right angles sufficiently far to include the quantity of land required, which somewhat exceeded 4.5 miles (7.2 km). Of these 24,000 acres (97 km2), 4,000 acres (16 km2) were awarded to John Gabriel Gervais for having pursued the grant; the remaining 20,000 acres (81 km2) were split into 92 lots of 217.4 acres (0.880 km2) each.

Another 1,200 acres (4.9 km2) additional were granted on June 25, 1798[2] called the Second Grant. These 150 acres (0.61 km2) lots adjoined the first Grant towards its lower end. This grant was for eight Gallipolis residents who did not receive a portion of the First Grant.

History

The “French Grant,” a tract of 24,000 acres (97 km2), is situated in the southeastern part of this county. “It was granted by Congress in March, 1795, to a number of French families who lost their lands at Gallipolis by invalid titles. It extended from a point on the Ohio river one and a half miles above, but opposite the mouth of Little Sandy creek in Kentucky, and extending eight miles (13 km) in a direct line down the river, and from the two extremities of that line, reaching back at right angles sufficiently far to include the quantity of land required, which somewhat exceeded four and a half miles.” 1,200 acres (4,900,000 m2) additional were, in 1798, granted, adjoining it towards its lower end. Of this tract 4,000 acres (16 km2) directly opposite Little Sandy creek were granted to Mons. J. G. GERVAIS, who laid out a town upon it which he called Burrsburg, which never had but a few inhabitants. Thirty years since there were but eight or ten families residing on the French Grant

Among the few Frenchmen that settled on the Grant were A. C. VINCENT, Claudius CADOT, Petre CHABOT, Francois VALODIN, Jean BERTRAND, Guillaume DUDUIT, Petre RUISHOND, Mons. GINAT, Doctor DUFLIGNY. The sufferings and hardships of these Frenchmen, so poorly adapted for pioneer life, were very great. (See Gallia County.) They were a worthy, simple-hearted people, and those who remained on the Grant eventually became thrifty and useful citizens.

It was in the spring of 1797 that the families of DUDUIT, BERTRAM, GERVAIS, LACROIX and DUTIEL located on their lots in the Grant. They were followed by others, but, as previously stated, only a comparatively small number removed from Gallipolis to Scioto county. In the very valuable series of biographical sketches of Scioto county pioneers, by Mr. Samuel KEYES, are many interesting items illustrative of the characteristics and life of these Frenchmen. We give the following:

Liberal Dealing Profitable.—M. DUTIEL, in selling grain, used a half-bushel measure a little larger than the law required. Some of his neighbors called his attention to the fact that he was giving more grain than was necessary, when he replied, “Well, I know it; but I would rather give too much than too little.” This becoming known, DUTIEL always sold out his surplus grain before his neighbors could sell a bushel.

Easily Scared.—Mons. DUDUIT, unlike most of his fellow-countrymen, took naturally to the woods, and soon became an expert hunter and woodsman. Before his removal to the Grant, he had been employed by Col. SPROAT to scour the woods between Marietta and the Scioto, in company with Major Robt. SAFFORD. It was their duty to notify the settlements of the approach of hostile Indians. On one occasion DUDUIT was out hunting with several of his countrymen, when he fired at and killed a deer; whereupon his companions, supposing they had been fired upon by Indians, fled to the settlement, and reported that the Indians had killed DUDUIT and were coming to raid the village. DUDUIT hung up his deer and hastened back to the village, which he found in an uproar and the settlers panic-stricken; but he soon quieted their fears, and induced some of them to assist him in bringing in the deer he had killed.

The Laziest Man in the World.—Petre RUISHOND was called the “laziest man in the world.” How he ever came to have energy enough to cross the ocean and work his way out to Ohio was a mystery to all who knew him. He spent a large portion of his time gazing at the stars and predicting future events, particularly changes in the weather. On one occasion a general meeting of the neighborhood was called for a certain date, to put up a bridge. “Big Pete,” as he was called, predicted rain on that date. Sure enough, it did rain. No almanac-maker could have found occupation on the French Grant after that.

RUISHOND was large, awkward and raw-boned. He never married, although often in love. He would go to see the fair object of his affections, but was too bashful to speak his love. He would sit and look at her all day without courage to say a word. He cleared only enough of his 217 acres (0.88 km2) of land to raise a few vegetables, just sufficient to support life. For weeks he would live on beans, which he boiled in large quantities to save building a fire too often. Occasionally he would trap a few turkeys, and then revel for a brief time in a change of diet. Finally his cabin burned down. He was too lazy to rebuild, but made a contract with one of his neighbors to keep him for the balance of his life in exchange for his 217 acres (0.88 km2) of land. He died about 1823.

A French Pettifogger.—Mons. GINAT had a medium education, and was quite useful to the French in the Grant, through his tact as a pettifogger. His mind seems to have been well adapted to this business, for he is said to have had a particular liking for disputation. He would always waive previous impressions and take the opposition on any question, simply for the sake of showing his talent and confusing his opponent. The French often had misunderstandings with the Yankees, and, as most of them spoke poor English, it was difficult for them always to obtain justice. M. GINAT had given much attention to law and spoke English fluently; he was therefore well prepared to advocate the causes of the French. He must have been expert in this craft, for men much dreaded him as an opponent.

A Peculiar Method of Cleaning Wheat.—“Petre CHABOT had a peculiar method of separating wheat from the chaff not practised much, because few could do it. He had what was called a fan. It was made of light boards, with a hoop around three sides about six inches wide. The front was left open, with handles at the sides. He would put in about a peck of wheat and chaff altogether, and would then take it up by the handles in front of him, and throw it up in such a manner that the wheat would fall back in the fan and at the same time blow the chaff out. By throwing it up in this way a few minutes the chaff would all be blown out and the wheat remain in the fan. I have seen negroes in Old Virginia clean hominy in a tray in that way that had been pounded with a hominy block. On account of Mons. CHABOT’s ability to clean wheat, he was employed by all his neighbors for the purpose of threshing and cleaning wheat.”

A Penurious Doctor.—Doctor DUFLIGNY left the reputation of extreme penuriousness. While keeping bachelor’s hall, two Frenchmen, VINCENT and MAGUET, called on the doctor just before dinner-time. “Well, Doctor,” they said, “we are very hungry and tired, and will have to trouble you for a little dinner.” Doctor, looking up sadly, sighing and rubbing his eyes, said, “Friends, I am very sorry it is so, but I have been very poorly for some days; have no appetite and have not cooked anything, nor have I prepared anything to cook.” The two, making themselves very free, opened the cupboard and continued, “Well, Doctor, as you are sick, we can cook a little for ourselves.” Doctor—“I don’t like to put you to so much trouble; besides I have nothing fit for you.” The two exclaimed, “Oh! no trouble! Why here are eggs, meat, flour, etc. Oh! we can get a good dinner of this.” One made a fire, the other made up some bread, and broke in plenty of eggs. At this the doctor exclaimed, “Oh! gentlemen, you can’t eat that.” The reply was, “Never mind, Doctor; don’t worry yourself.” They prepared a good dinner, put it on the table, and were about to partake, when the doctor remarked, “Well, gentlemen, your victuals smell so well, my appetite seems to come to me. I think a little of your dinner cannot hurt me and may help me.” Whereupon he drew up his chair, and eat a very hearty dinner with his importunate guests.

A Suicide.—M. ANTOINME, a jeweler, who had brought his stock in trade to Gallipolis, finding there was no demand for his goods in the backwoods of Ohio, concluded to take them down the river to New Orleans. It was in the autumn of 1791 that he procured a large pirogue and had it manned by two hired men. Besides a vast amount of watches and jewelry, he took with him a supply of firearms for defensive purposes. The party fared well until within a short distance of the mouth of the Big Sandy, when a party of Indians appeared on the river bank.

ANTOINME seized a musket and prepared to fire on the Indians, when his cowardly hirelings became panic-stricken and threatened him with instant death if he dared fire at them and thus provoke their anger. ANTOINME in despair over the prospect of losing all his possessions, placed the musket to his head and blew out his brains. At the report of the gun the Indians turned to flee, but the hired men called them back, saying the man had only shot himself. The Indians boarded the pirogue, threw ANTOINME’S body overboard after rifling it, and took possession of such ammunition, provisions, arms, clothing and jewelry as suited their fancy. Much jewelry, tools, watches, etc., of which they could see no value, were thrown overboard and it is said that for many years afterwards watch crystals, etc., were found near this place. The Indians gave the cowardly hirelings two blankets and a loaf of bread each and sent them to the fort at Cincinnati.

A Scholarly Pioneer.—Antoine Claude VINCENT settled on the grant as a farmer. He had been educated in France for a Roman Catholic priest, but his liberal opinions prevented his ordination, and he became a silversmith, and came to Gallipolis in the service of M. ANTOINME, whose tragic death we have related.

VINCENT settled in Gallipolis, afterward taught school in Marietta. It was while teaching school at the latter place and boarding at a hotel, that Louis PHILIPPE with two relatives, traveling incognito visited the same hotel. There were many French then in Marietta and being favorably disposed to the Royalists’, Louis PHILIPPE made himself known to them. The Duke of Orleans (Louis PHILIPPE) and his relatives were on their way to New Orleans, and sought some one to accompany them. Louis himself was very dejected and gloomy and sat with his “chapeau” far over his eyes, his face downcast and supported by his hands. He rarely spoke, but his relatives had the free use of their tongues. They were much pleased with Mons. VINCENT and greatly desired him to share their fortune and accompany them to the city of New Orleans; and as the two relatives seemed about to fail in their object, the future sovereign of France broke his gloomy silence and with honest tears streaming from his eyes said, “Yes, come along with us, VINCENT, come; we are now wretched outcasts, alone, friendless, homeless, moneyless, wandering through this wilderness infested with wild beasts and worse savages, far from our dear native land. We need you now, and yet can repay you nothing, but the time will come when we can and will; law and order will soon be restored; we will wait that occasion and then peaceably return and be restored to our possessions and rights. Then we can and will repay you; we will have offices to fill and titles to confer. They will be yours, only come with us now in our distress.” Louis and his companions, however, could not prevail on M. VINCENT to accompany them.

A Copperhead.—Some time after this VINCENT was living alone in a house in the wilderness. He had occasion to get up one night, when he felt something, which he thought was a wire strike his foot repeatedly. He was soon convinced, however, that it was a snake and he started for the village to seek a physician. Before he could reach the village his feet were so swollen, that he was obliged to crawl the last quarter of a mile. The physician pronounced the bite that of a copperhead, and for three weeks VINCENT lay at the point of death, during which time he suffered excruciating agony, in his paroxysms literally gnawing to pieces the blanket which was his covering.

Lost in a Snow Storm.—On another occasion VINCENT was overtaken in the night by a severe snow-storm, lost his way, was overcome by the cold and fell to the ground unconscious. Recovering consciousness in a short time he discovered that the storm had passed over and near by stood a house. He endeavored to rise, but his feet were frozen and he found he could only move by dragging himself along, using his elbows. After much painful effort he reached the house, and his cries soon brought assistance. For six weeks it was a question if he would survive his terrible experience, but, by the external use of lime water, his flesh was healed, although not with the loss of most of the first joints of his hands and feet.

Notwithstanding his sore experiences Mons. VINCENT lived a long and useful life, during which he became wealthy, reared a large family and held the high respect of all who knew him. He was a man of liberal education, read VOLTAIRE and ROUSSEAU, and while in his Western home, was a student of history, philosophy, mathematics, ethics and music. He was a find musician, being a great lover of the flute and violin, both of which he played well until he lost part of his fingers by freezing. He died August 22, 1846, in his 74th year.

See also

References

- ↑ 1 Stat. 442 - Text of Act of March 3, 1795 Library of Congress

- ↑ 6 Stat. 35 - Text of Act of June 25, 1798 Library of Congress

External links

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~henryhowesbook/scioto.html