French franc

| French franc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| franc français (French) | |||||

| |||||

| ISO 4217 | |||||

| Code | FRF | ||||

| Number | 250 | ||||

| Exponent | 2 | ||||

| Denominations | |||||

| Subunit | |||||

| 1⁄100 | centime | ||||

| Symbol | F or Fr (briefly also NF during the 1960s; also unofficially FF and ₣) | ||||

| Nickname | balles (1 F);[1][n 1] sacs (10 F); bâton, brique, patate, plaque (10,000 F) | ||||

| Banknotes | 20 F, 50 F, 100 F, 200 F, 500 F | ||||

| Coins | 1, 5, 10, 20 centimes, 1⁄2 F, 1 F, 2 F, 5 F, 10 F, 20 F | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| User(s) |

None; previously: France, Monaco, Andorra (until 2002); Saar, Saarland (until 1959) | ||||

| Issuance | |||||

| Central bank | Banque de France | ||||

| Website |

www | ||||

| Mint | Monnaie de Paris | ||||

| Website |

www | ||||

| Valuation | |||||

| Pegged by | KMF, XAF & XOF, XPF, ADF, MCF | ||||

| ERM | |||||

| Since | 13 March 1979 | ||||

| Fixed rate since | 31 December 1998 | ||||

| Replaced by €, non cash | 1 January 1999 | ||||

| Replaced by €, cash | 1 January 2002 | ||||

| € = | 6.55957 F | ||||

|

This infobox shows the latest status before this currency was rendered obsolete. | |||||

The franc (/fræŋk/; French: [fʁɑ̃]; sign: F or Fr),[n 2] also commonly distinguished as the French franc (FF), was a currency of France. Between 1450 and 1999, it was the name of coins worth 1 livre tournois and it remained in common parlance as a term for this amount of money. It was reintroduced (in decimal form) in 1795. It was revalued in 1960, with each new franc (NF) being worth 100 old francs. The NF designation was continued for a few years before the currency returned to being simply the franc; the French continued to reference and value items in terms of the old franc (equivalent to the new centime) until the introduction of the euro in 1999 (for accounting purposes) and 2002 (for coins and banknotes). The French franc was a commonly held international reserve currency of reference in the 19th and 20th centuries.

History

Before the French Revolution

The first franc was a gold coin introduced in 1360 to pay the Ransom of King John II of France. This coin secured the king's freedom and showed him on a richly decorated horse earning it the name franc à cheval (meaning "free on horse" in French).[4] The obverse legend, like other French coins, gives the king’s title as Francorum Rex ("King of the Franks" in Latin) and provides another reason to call the coin a franc. Its value was set as one livre tournois (a money of account). John’s son, Charles V, continued this type. It was copied exactly at Brabant and Cambrai and, with the arms on the horse cloth changed, at Flanders. Conquests led by Joan of Arc allowed Charles VII to return to sound coinage and he revived the franc à cheval. John II, however, was not able to strike enough francs to pay his ransom and he voluntarily returned to English captivity.

John II died as a prisoner in England and his son, Charles V was left to pick up the pieces. And so he did. Charles V pursued a policy of reform, including stable coinage. An edict dated 20 April 1365 established the centerpiece of this policy, a gold coin officially called the denier d’or aux fleurs de lis which had a standing figure of the king on its obverse. Its value in money of account was one livre tournois, just like the franc à cheval, and this coin is universally known as a franc à pied. In accordance with the theories of the mathematician, economist and royal advisor Nicolas Oresme, Charles struck fewer coins of better gold than his predecessors. In the accompanying deflation both prices and wages fell, but wages fell faster and debtors had to settle up in better money than they had borrowed. The Mayor of Paris, Etienne Marcel, exploited their discontent to lead a revolt which forced Charles V out of the city. The franc fared better. It became associated with money stable at one livre tournois[5]

Henry III exploited the association of the franc as sound money worth one livre tournois when he sought to stabilize French currency in 1577. By this time, inflows of gold and silver from Spanish America had caused inflation throughout the world economy and the kings of France, who weren’t getting much of this wealth, only made things worse by manipulating the values assigned to their coins. The States General which met at Blois in 1577 added to the public pressure to stop currency manipulation. Henry III agreed to do this and he revived the franc, now as a silver coin valued at one livre tournois. This coin and its fractions circulated until 1641 when Louis XIII of France replaced it with the silver Écu. Nevertheless, the name "franc" continued in accounting as a synonym for the livre tournois.[6]

French Revolution

The decimal "franc" was established as the national currency by the French Revolutionary Convention in 1795 as a decimal unit (1 franc = 10 décimes = 100 centimes) of 4.5 g of fine silver. This was slightly less than the livre of 4.505 g, but the franc was set in 1796 at 1.0125 livres (1 livre, 3 deniers), reflecting in part the past minting of sub-standard coins. Silver coins now had their denomination clearly marked as “5 FRANCS” and it was made obligatory to quote prices in francs. This ended the ancien régime’s practice of striking coins with no stated denomination, such as the Louis d'or, and periodically issuing royal edicts to manipulate their value in terms of money of account, i.e. the Livre tournois.

Coinage with explicit denominations in decimal fractions of the franc also began in 1795.[7] Decimalization of the franc was mandated by an act of 7 April 1795, which also dealt with of weights and measures. France led the world in adopting the metric system and it was the second country to convert from a non-decimal to a decimal currency, following Russia’s conversion in 1704,[8] and the third country to adopt a decimal coinage, also following the United States in 1787.[9] France’s first decimal coinage used allegorical figures symbolizing revolutionary principles, like the coinage designs the United States had adopted in 1793.

.jpg)

The circulation of this metallic currency declined during the Republic: the old gold and silver coins were taken out of circulation and exchanged for printed assignats, initially issued as bonds backed by the value of the confiscated goods of churches, but later declared as legal tender currency. The withdrawn gold and silver coins were used to finance wars and to import food, which was in short supply.

As during the "Mississippi Bubble" in 1715-20, too many assignats were put in circulation, exceeding the value of the "national properties", and the coins, due also to military requisitioning and hoarding, rarefied to pay foreign suppliers. With national government debt remaining unpaid, and a shortage of silver and brass to mint coins, confidence in the new currency declined, leading to hyperinflation, more food riots, severe political instability and termination of the First French Republic and the political fall of the French Convention. Then followed the economic failure of the Directoire: coins were still very rare. After a coup d'état that led to the Consulate, the First Consul progressively acquired sole legislative power at the expense of the other unstable and discredited consultative and legislative institutions.

French Empire and Restoration

In 1800 the Banque de France, a federal establishment with a private board of executives, was created and commissioned to produce the national currency. In 1803, the Franc germinal (named after the month Germinal in the revolutionary calendar) was established, creating a gold franc containing 290.034 mg of fine gold. From this point, gold and silver-based units circulated interchangeably on the basis of a 1:15.5 ratio between the values of the two metals (bimetallism) until 1864, when all silver coins except the 5-franc piece were debased from 90% to 83.5% silver without the weights changing.

This coinage included the first modern gold coins with denominations in francs. It abandoned the revolutionary symbols of the coinage 1795, now showing Napoleon in the manner of Roman emperors, first described as “Bonaparte Premier Consul” and with the country described as “Republique Française”. The republican pretense faded fast. In 1804 coins changed the obverse legend to Napoleon Emperor, abandoning his family name in the manner of kings. In 1807, the reverse legend changed to describe France as an empire not a republic. In analogy with the old Louis d'or these coins were called Gold Napoleons. Economically, this sound money was a great success and Napoleon’s fall did not change that. Succeeding governments maintained Napoleon’s weight standard, with changes in design which traced the political history of France. In particular, this currency system was retained during the Bourbon Restoration and perpetuated until 1914.

Latin Monetary Union

France was a founding member of the Latin Monetary Union (LMU) in 1865. The common currency was based on the franc germinal, with the name franc already being used in Switzerland and Belgium, whilst other countries used their own names for the currency. In 1873, the LMU went over to a purely gold standard of 1 franc = 0.290322581 grams of gold.

World War I

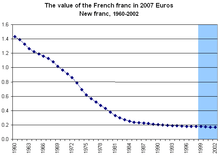

The outbreak of World War I caused France to leave the gold standard of the LMU. The war severely undermined the franc's strength: war expenditure, inflation and postwar reconstruction, financed partly by printing ever more money, reduced the franc's purchasing power by 70% between 1915 and 1920 and by a further 43% between 1922 and 1926. After a brief return to the gold standard between 1928 and 1936, the currency was allowed to resume its slide, until in 1959 it was worth less than 2.5% of its 1934 value.

World War II

During the Nazi occupation of France (1940–44), the franc was a satellite currency of the German Reichsmark. The exchange rate was 20 francs for 1 RM. The coins were changed, with the words Travail, Famille, Patrie (Work, Family, Fatherland) replacing the Republican triad Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, Fraternity) and the emblem of the Vichy regime added.

At the liberation, the US attempted to impose use of the US occupation franc, which was averted by General De Gaulle.

Post-War period

After World War II, France devalued its currency within the Bretton Woods system on several occasions. Beginning in 1945 at a rate of 480 francs to the British pound (119.1 to the U.S. dollar), by 1949 the rate was 980 to the pound (350 to the dollar). This was reduced further in 1957 and 1958, reaching 1382.3 to the pound (493.7 to the dollar, equivalent to 1 franc = 1.8 mg pure gold).

New franc

In January 1960 the French franc was revalued, with 100 existing francs making one nouveau franc.[10] The abbreviation "NF" was used on the 1958 design banknotes until 1963. Old one- and two-franc pieces continued to circulate as centimes (no new centimes were minted for the first two years). The one-centime coin never circulated widely. Inflation continued to erode the franc's value: between 1950 and 1960, the price level increased 72 per cent (5.7% per year on average); between 1960 and 1970, it increased 51 per cent (4.2%).[11] Only one further major devaluation occurred (11% in August 1969) before the Bretton Woods system was replaced by free-floating exchange rates. When the euro replaced the franc on 1 January 1999, the franc was worth less than an eighth of its original 1960 purchasing power.

After revaluation and the introduction of the new franc, many French people continued to use old francs (anciens francs), to describe large sums (throughout the 1980s and well in to the 1990s and virtually until the introduction of the euro, many people, old and young – even those who had never used the old franc – were still referring to the old franc, confusing people). For example, lottery prizes were most often advertised in amounts of centimes, equivalent to the old franc, basically to inflate the perceived value of the prizes at stake. Multiples of 10NF were occasionally referred to as "mille francs" (thousand francs) or "mille balles" ("balle" being a slang word for franc) in contexts where it was clear that the speaker did not mean 1,000 new francs. The expression "heavy franc" (franc lourd) was also commonly used to designate the new franc.

All franc coins and banknotes ceased to be legal tender in January 2002, upon the official adoption of the euro.

Economic and Monetary Union

From 1 January 1999, the value exchange rate of the French franc against the euro was set at a fixed parity of €1 = 6.55957 F. Euro coins and notes replaced the franc entirely between 1 January and 17 February 2002.

Coins

Before World War I

In August 1795, the Monetary Law replaced the livre ("pound") with the franc, which was divided into 10 décimes ("tenths") and 100 centimes ("hundredths"). Copper coins were issued in the denominations of 1 centime, 5 centimes, 1 décime, and 2 décimes, designed by Augustin Dupré. After 1801, French copper coins became rare.

The 5-centime copper coin was called a sou, referring to "sole" (fr. Latin: solidus), until the 1920s.

An Imperial 10-décime coin was produced in billon from 1807 to 1810.

During the Consulship period (1799–1804) silver francs were struck in decimal coinage.[12] A five-franc coin was first introduced in 1801–02 (L’AN 10),[13] half-franc, one-franc, and gold 40-franc coins were introduced in 1802–03 (L’AN 11),[14] and quarter-franc and two-franc coins in 1803–04 (L’AN 12).[15]

The 5-franc silver coin was called an écu, after the six-livre silver coin of the ancien regime, until the 1880s.

Copper coins were rarely issued between 1801 and 1848, so the quarter franc was the lowest current denomination in circulation. But during this period, copper coins from earlier periods circulated. A Napoleon 5-centime coin (in bell metal) and Napoleon and Restoration 1-décime coins were minted.

A new bronze coinage was introduced from 1848. The Second Republic Monetary Authority minted a 1-centime copper coin with a 1795 design. 2, 5 and 10-centime coins were issued from 1853. The quarter franc was discontinued, with silver 20-centime coins issued between 1849 and 1868 as the smallest silver coin produced in France.

The gold coinage also changed. 40-franc coins were last struck in 1839 (with just 23 coins minted).[16] Several new denomination were introduced as gold coinage: 5 gold francs (1856),[17] 10 gold francs (1850),[18] 50 gold francs (1855),[17] and 100 gold francs (1855).[19] A second design for the 100 gold franc coin was released in 1878 depicting standing genius writing the constitution.[20] The pictured example (1889) was issued as a proof and only 100 coins were struck.[20]

The last gold 5-franc pieces were minted in 1869, and silver 5-franc coins were last minted in 1878. After 1815, the 20-franc gold coin was called a "napoléon" (royalists still called this coin a "louis"), and so that is the colloquial term for this coin until the present. During the Belle Époque, the 100-franc gold coin was called a "monaco", referring to the flourishing casino business in Monte Carlo.

Nickel 25-centime coins were introduced in 1903.

World War I

World War I and the aftermath brought substantial changes to the coinage. Gold coinage was suspended and the franc was debased. Smaller, holed 5, 10, and 25-centime coins minted in nickel or cupro-nickel were introduced in 1914, finally replacing copper in 1921. In 1920, 1 and 2-centime coins were discontinued and production of silver coinage ceased, with aluminum-bronze 50-centime, 1-franc, and 2-franc coins introduced. Until 1929, these coins were issued by local merchants' associations, bearing the phrase bon pour on it (meaning: "good for"). At the beginning of the 1920s, merchants' associations also issued small change coins in aluminum. In 1929, the original franc germinal of 1795 was replaced by the franc Poincaré, which was valued at 20% of the 1803 gold standard.

In 1929, silver coins were reintroduced in 10-franc and 20-franc denominations. A very rare gold 100-franc coin was minted between 1929 and 1936.

In 1933, a nickel 5-franc coin was minted, but was soon replaced by a large aluminum-bronze 5-franc coin.

From World War II to the currency reform

The events of Second World War also affected the coinage substantially. In 1941, aluminum replaced aluminum-bronze in the 50 centimes, and 1, 2, and 5 francs as copper and nickel were diverted into the War Effort. In 1942, following German occupation and the installation of the French Vichy State, a new, short lived series of coins was released which included holed 10 and 20 centimes in zinc. 50 centimes, and 1 and 2 francs were aluminum. In 1944 this series was discontinued and withdrawn and the previous issue was resumed.

Following the war, rapid inflation caused denominations below 1 franc to be withdrawn from circulation while 10 francs in copper nickel were introduced, followed by reduced size 10-franc coins in aluminum-bronze in 1950, along with 20 and 50-franc coins of the same composition. In 1954, copper-nickel 100 francs were introduced.

In the 1960s, 1 and 2 (old) franc aluminum coins were still circulating, used as "centimes".

New franc

In 1960, the new franc (nouveau franc) was introduced,[21] worth 100 old francs. Stainless steel 1 and 5 centimes, aluminium-bronze 10, 20, and 50 centimes, nickel 1 franc and silver 5 francs were introduced. Silver 10-franc coins were introduced in 1965, followed by a new, smaller aluminium-bronze 5-centime and a smaller nickel 1⁄2-franc coin in 1966.

There was also a first attempt to introduce a nickel 2-franc coin in 1960 that failed.

Nickel-clad copper-nickel 5-franc and nickel-brass 10-franc coins replaced their silver counterparts in 1970 and 1974, respectively. Nickel 2 francs were finally introduced in 1979, followed by bimetallic 10 francs in 1988 and trimetallic 20 francs in 1992. The 20-franc coin was composed of two rings and a centre plug.

| 20 Centime with Marianne on Obverse. | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Obverse: Marianne wearing the Phrygian cap of liberty. | Reverse: Face value and French motto: "Liberté, égalité, fraternité". |

| This coin was minted from 1962 to 2001. | |

A nickel 10-franc piece was issued in 1986, but was quickly withdrawn and demonetized due to confusion with the half-franc and an unpopular design. This led to the conception of the later bimetallic model. The aluminium-bronze pieces continued to circulate until the bimetallic pieces were developed and additional aluminium-bronze coins were minted to replace those initially withdrawn. Once the bimetallic coins were circulating and produced in necessary quantities, the aluminium-bronze pieces were gradually withdrawn and demonetized.

A .900 silver 50-franc piece was issued from 1974–1980, known as the largest silver coin ever minted in France, (due to its face value in accordance to its size) but was withdrawn and demonetized after the price of silver spiked in 1980. Then, in 1982, a 100-franc piece, also in .900 silver, was issued, and circulated to a small extent, until the introduction of the euro.

All French franc coins were demonetized in 2005 and are no longer redeemable at the Banque de France.

At the time of the complete changeover to the euro on 1 January 2002, coins in circulation (some produced as recently as 2000) were:

- 1 centime (~ 0.15 euro cents) stainless steel, rarely circulated (last production stopped first in 1982, then in 1987 due to high production cost, and lack of demand due to its very low value).

- 5 centimes (~ 0.76 cents) aluminium-bronze

- 10 centimes (~ 1.52 cents) aluminium-bronze

- 20 centimes (~ 3.05 cents) aluminium-bronze

- 1⁄2 franc (~ 7.6 cents) nickel

- 1 franc (~ 15.2 cents) nickel

- 2 francs (~ 30.5 cents) nickel

- 5 francs (~ 76 cents) nickel-clad copper-nickel

- 10 francs (~ €1.52) bimetallic

- 20 francs (~ €3.05) trimetallic, rarer (produced for a short period before the euro, the banknote equivalent was much more frequently used)

- 100 francs (~ €15.24) silver, rarely circulated (most often bought and offered as personal gifts, but rare in commercial transactions, now worth more than its face value).

Euro exchange

Coins were freely exchangeable until 17 February 2005 at Banque de France only (some commercial banks also accepted the old coins but were not required to do so for free after the transition period in 2001), by converting their total value in francs to euros (rounded to the nearest cent) at the fixed rate of 6.55957 francs for 1 euro. Banknotes remained convertible up until 17 February 2012.[22] By that date, franc notes worth some €550 million remained unexchanged, allowing the French state to register the corresponding sum as revenue.[23]

Banknotes

.jpg)

.jpg)

The first franc paper money issues were made in 1795. They were assignats in denominations between 100 and 10,000 francs. These followed in 1796 by "territorial mandate promises" for 25 up to 500 francs. The treasury also issued notes that year for 25 up to 1000 francs.

In 1800, the Bank of France began issuing notes, first in denominations of 500 and 1000 francs. In the late 1840s, 100 and 200-franc notes were added, while 5, 20 and 50 francs were added in the 1860s and 70s, although the 200-franc note was discontinued.

The First World War saw the introduction of 10 and 1000-franc notes. The chambers of commerce's notgeld ("money of necessity"), from 1918 to 1926, produced 25c, 50c, 1 F, 2 F, 5 F, and 10 F notes.

Despite base-metal 5, 10 & 20 F coins being introduced between 1929 and 1933, the banknotes were not removed. In 1938, first 5000-franc notes were added.

In 1944, the liberating Allies introduced dollar-like paper money in denominations between 2 and 1000 francs, as well as a brass 2-franc coin.

After the Second World War, while 5, 10 and 20-franc notes were replaced by coins in 1950, as were the 50- and 100-franc notes in the mid-1950s. In 1954, the 10,000-franc notes were introduced.

In 1959, banknotes in circulation when the old franc was replaced by the new franc were:

- 500 francs: Victor Hugo

- 1000 francs: Cardinal de Richelieu

- 5000 francs: Henri IV

- 10,000 francs: Bonaparte 1st consul

The first issue of the new franc consisted of 500, 1000, 5000 and 10,000-franc notes overprinted with their new denominations of 5, 10, 50 and 100 new francs. This issue was followed by notes of the same design but with only the new denomination shown. A 500-new franc note was also introduced in 1960 representing Molière, replaced in 1969 by the yellow Pascal type (colloquially called a pascal). A 5-franc note was issued until 1970 and a 10-franc note (showing Hector Berlioz) was issued until 1979.

Banknotes in circulation when the franc was replaced were:[24]

- 20 francs (€3.05): Claude Achille Debussy-brown-purple (introduced 1983)

- 50 francs (€7.62): Antoine de Saint-Exupéry—blue (introduced 20 October 1993, replacing Maurice Quentin de la Tour)

- 100 francs (€15.24): Paul Cézanne—orange (introduced 15 December 1997, replacing Eugène Delacroix)

- 200 francs (€30.49): Gustave Eiffel—red (introduced 29 October 1996, replacing Montesquieu)

- 500 francs (€76.22): Pierre and Marie Curie—green (introduced 22 March 1995, replacing Blaise Pascal)

Banknotes of the current series as of euro changeover could be exchanged with the French central bank or with other services until 17 February 2012.

Most older series were exchangeable for 10 years from date of withdrawal. As the last banknote from the previous series had been withdrawn on 31 March 1998 (200 francs, Montesquieu), the deadline for the exchange was 31 March 2008.

.jpg) 10-franc banknote (1976) (front) Hector Berlioz

10-franc banknote (1976) (front) Hector Berlioz.jpg) 10-franc banknote (1976) (back) Hector Berlioz

10-franc banknote (1976) (back) Hector Berlioz- 20-franc banknote (1983) (front) Claude-Achille Debussy

20-franc banknote (1983) (back) Claude-Achille Debussy

20-franc banknote (1983) (back) Claude-Achille Debussy 100 francs Eugène Delacroix

100 francs Eugène Delacroix 50 francs Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

50 francs Antoine de Saint-Exupéry 100 francs Paul Cézanne

100 francs Paul Cézanne 200 francs Gustave Eiffel

200 francs Gustave Eiffel 500 francs Marie Curie and Pierre Curie

500 francs Marie Curie and Pierre Curie

| Banknotes of the French franc (1993–1997 issue) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Value | Equivalent in euros | Size | Obverse | Reverse | Watermark | Remark | Date of issue |

| [25] | 50 F | €7.62 | 123 x 80 mm | Antoine de Saint-Exupéry; Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince); "Latécoère 28" airplane | "Breguet 14" biplane | Antoine de Saint-Exupéry | In the notes printed in 1992-1993, the name of Saint-Exupéry was misspelled as Éxupéry at upper left on front | October 20, 1993 |

| [26] | 100 F | €15.24 | 133 x 80 mm | Paul Cézanne | Fruit (a painting by Paul Cézanne) | Paul Cézanne | EURion constellation on the upper right corner of the note's reverse consisting of 100s spread across. | December 15, 1997 |

| [27] | 200 F | €30.49 | 143 x 80 mm | Gustave Eiffel; truss of the Eiffel tower | Base of the Eiffel tower | Gustave Eiffel | October 29, 1996 | |

| [28] | 500 F | €76.22 | 153 x 80 mm | Marie Curie and Pierre Curie | Laboratory utensils | Marie Curie | March 22, 1995 | |

De facto currency

Along with the Spanish peseta, the French franc was also a de facto currency used in Andorra (which had no national currency with legal tender). It circulated alongside the Monegasque franc, as it did in Monaco, with which it had equal value. These currencies were all replaced by the euro in 2002.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Always used in plural and chiefly in reference to the old franc, so that the new francs and the euro were known as cent balles (100 old francs).

- ↑ An F-with-bar or Fr ligature (₣) is available as a Unicode currency symbol character but was never adopted and has never been officially used.[2] The F-with-bar symbol was proposed by Édouard Balladur, Minister of Economy, in 1988.[3]

References

Citations

- ↑ de Goncourt, E. & J. (1860), Charles Demailly, p. 107.

- ↑ Haralambous, Yannis (2007), Fonts & Encodings, p. 78.

- ↑ Balladur, Édouard (1988), Un symbole pour le franc.

- ↑ Coins of Medieval Europe. Philip Grierson. p. 145.

- ↑ Coins in History. John Porteous. P. 116

- ↑ Coins in History. John Porteous. P. 182

- ↑ Coins of the World, W. D. Craig, page 100 of the second edition

- ↑ The Coin Atlas, Cribb, Cook, Carradice, and Flower, page 119

- ↑ The Coin Atlas, Cribb, Cook, Carradice, and Flower, page 266

- ↑ Ordonnance n°58-1341 du 27 décembre 1958 NOUVEAU FRANC

- ↑ Otmar Emminger: DM, Dollar, Währungskrisen – Erinnerungen eines ehemaligen Bundesbankpräsidenten, 1986, p. 75.

- ↑ Cuhaj 2009, p. 321.

- ↑ Cuhaj 2009, p. 323.

- ↑ Cuhaj 2009, pp. 322-24.

- ↑ Cuhaj 2009, pp. 321-23.

- ↑ Cuhaj 2009, p. 345.

- 1 2 Cuhaj 2009, p. 351.

- ↑ Cuhaj 2009, p. 348.

- ↑ Cuhaj 2009, p. 353.

- 1 2 Cuhaj 2009, p. 356.

- ↑ 1958 Monetary Law Reform voted along with the Fifth Republic Constitution.

- ↑ http://www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/exchange/html/index.en.html

- ↑ Erlanger, Steven (19 February 2012). "As Old Francs Expire, France Makes a Small Mint". New York Times. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ http://www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/exchange/fr/html/index.en.html

- ↑ http://banknote.ws/COLLECTION/countries/EUR/FRA/FRA0157.htm

- ↑ http://banknote.ws/COLLECTION/countries/EUR/FRA/FRA0158.htm

- ↑ http://banknote.ws/COLLECTION/countries/EUR/FRA/FRA0159.htm

- ↑ http://banknote.ws/COLLECTION/countries/EUR/FRA/FRA0160.htm

Bibliography

- Cuhaj, George S., ed. (2009). Standard Catalog of World Coins 1801–1900 (6 ed.). Krause. ISBN 978-0-89689-940-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Banknotes of France. |

- Overview of French franc from the BBC

- Banknotes of France

- French franc (1951-1999) and euro (1999-ongoing) inflation calculators and charts

- Banknotes of France: Detailed Catalog of French Francs

- Historical banknotes of France (in English) (in German)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)