Education in France

| |

| Ministry of National Education | |

|---|---|

| Minister Deputy Minister | Jean-Michel Blanquer |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | French |

| System type | Central |

| Literacy (2003) | |

| Total | 991 |

| Male | 99 |

| Female | 99 |

| Enrollment | |

| Total | 15.0 million2 |

| Primary | 6.7 million |

| Secondary | 4.8 million |

| Post secondary | 2.3 million3 |

| Attainment | |

| Secondary diploma | 79.7% |

| Post-secondary diploma | 27% |

|

1As of 2004, literacy rates are no longer collected within INSEE censuses. 2Includes private education. 3Includes universities, CPGE, and technical schools. | |

The French educational system is highly centralized and organized, with many subdivisions. It is divided into the three stages of enseignement primaire (primary education), enseignement secondaire (secondary education), and enseignement supérieur (higher education). In French higher education, the following degrees are recognized by the Bologna Process (EU recognition): Licence and Licence Professionnelle (bachelor's degrees), and the comparably named Master and Doctorat degrees.

History

While the French trace the development of their educational system to Napoléon, the modern era of French education begins at the end of the nineteenth century. Jules Ferry, a Minister of Public Instruction in the 1880s, is widely credited for creating the modern school (l'école républicaine) by requiring all children between the ages of 6 and 12, both boys and girls, to attend. He also made public instruction mandatory, free of charge, and secular (laïque). With these laws, known as French Lubbers, Jules Ferry laws, and several others, the Third Republic repealed most of the Falloux Laws of 1850–1851, which gave an important role to the clergy.

Governance

All educational programmes in France are regulated by the Ministry of National Education (officially called Ministère de l'Éducation nationale, de la Jeunesse et de la Vie associative). The head of the ministry is the Minister of National Education.

The teachers in public primary and secondary schools are all state civil servants, making the ministère the largest employer in the country. Professors and researchers in France's universities are also employed by the state.

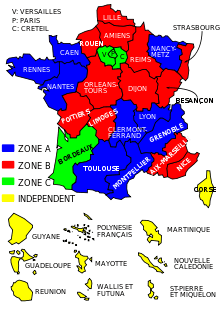

| Zone | Académies/Cites |

|---|---|

| A | Caen, Clermont-Ferrand, Grenoble, Lyon, Montpellier, Nancy-Metz, Nantes, Rennes, Toulouse |

| B | Aix-Marseille, Amiens, Besançon, Dijon, Lille, Limoges, Nice, Orléans-Tours, Poitiers, Reims, Rouen, Strasbourg |

| C | Bordeaux, Créteil, Paris, Versailles |

At the primary and secondary levels, the curriculum is the same for all French students in any given grade, which includes public, semi-public and subsidised institutions. However, there exist specialised sections and a variety of options that students can choose. The reference for all French educators is the Bulletin officiel de l'éducation nationale, de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche (B.O.) which lists all current programmes and teaching directives. It is amended many times every year.[1]

School year

In Metropolitan France, the school year runs from early September to early July. The school calendar is standardized throughout the country and is the sole domain of the ministry.

In May, schools need time to organise exams (for example, the baccalauréat). Outside Metropolitan France, the school calendar is set by the local recteur.

Major holiday breaks are as follows:

- All Saints (la Toussaint), two weeks (since 2012) around the end of October and the beginning of November;

- Christmas (Noël), two weeks around Christmas Day and New Year's Day;

- winter (hiver), two weeks starting in mid February;

- spring (printemps) or Easter (Pâques), two weeks starting in mid April;

- summer (été), two months starting in early July. (mid-June for high school students).

Kindergarten and primary school

| École maternelle (Kindergarten/Nursery School/Pre-school) | ||

| Age | Grade | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| 3–4 | Petite section | PS |

| 4–5 | Moyenne section | MS |

| 5–6 | Grande section | GS |

| École primaire (Primary School) | ||

| 6–7 | Cours préparatoire | CP, 11ème, or 11e |

| 7–8 | Cours élémentaire première année | CE1, 10ème, or 10e |

| 8–9 | Cours élémentaire deuxième année | CE2, 9ème, or 9e |

| 9–10 | Cours moyen première année | CM1, 8ème, or 8e |

| 10–11 | Cours moyen deuxième année | CM2, 7ème, or 7e |

| Collège (Junior High/Middle School) | ||

| Age | Grade | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| 11–12 | Sixième | 6ème or 6e |

| 12–13 | Cinquième | 5ème or 5e |

| 13–14 | Quatrième | 4ème or 4e |

| 14–15 | Troisième | 3ème or 3e |

| Lycée (High school/Secondary School) | ||

| Age | Grade | Abbreviation |

| 15–16 | Seconde | 2nde or 2de |

| 16–17 | Première | 1ère |

| 17–18 | Terminale | Term |

Schooling in France is mandatory from age 6, the first year of primary school, this year being named cours préparatoire (preparatory class). Most parents start sending their children at age 3, at kindergarten classes (maternelle), which are usually affiliated to a borough's primary school. Some even start earlier at age 2 in pré-maternelle or très petite section classes, which are essentially daycare centres. The last year of kindergarten, grande section ("big form") is an important step in the educational process, as it is the year in which pupils are introduced to reading.

After kindergarten, the young students move on to primary school. It is in the first year that they will learn to write and develop their reading skills. Much akin to other educational systems, French primary school students usually have a single teacher (or perhaps two) who teaches the complete curriculum, such as French, mathematics, science and humanities to name a few. Note that the French word for a teacher at the primary school level is maître or its feminine form maîtresse (previously called instituteur, or its feminine form institutrice).

Middle school and high school

After primary school, two educational stages follow:

- collèges (middle school), which cater for the first four years of secondary education from the ages of 11 to 15

- lycées (high school), which provide a three-year course of further secondary education for children between the ages of 15 and 18. Pupils are prepared for the baccalauréat (baccalaureate, colloquially known as le bac). The baccalauréat can lead to higher education studies or directly to professional life.

International education

As of January 2015, the International Schools Consultancy (ISC)[2] listed France as having 105 international schools.[3] ISC defines an 'international school' in the following terms "ISC includes an international school if the school delivers a curriculum to any combination of pre-school, primary or secondary students, wholly or partly in English outside an English-speaking country, or if a school in a country where English is one of the official languages, offers an English-medium curriculum other than the country’s national curriculum and is international in its orientation."[3] This definition is used by publications including The Economist.[4]

Higher education

Higher education in France is organized in three levels or grades which correspond to those of other European countries, facilitating international mobility: the Licence and Licence Professionnelle (bachelor's degrees), and the Master's and Doctorat degrees. The Licence and the Master are organized in semesters: 6 for the Licence and 4 for the Master.[5][6] These levels of study include various "parcours" or paths based on UE (Unités d’Enseignement or Modules), each worth a defined number of European credits (ECTS); a student accumulates these credits, which are generally transferable between paths. A Licence is awarded once 180 ECTS have been obtained; a Master is awarded once 120 additional credits have been obtained.[5][6]

Licence and master's degrees are offered within specific domaines and carry a specific mention. Spécialités which are either research-oriented or professionally oriented during the second year of the Master. There are also Professional Licences whose objective is immediate job integration. It is possible to later return to school through continuing education or to validate professional experience (through VAE, Validation des Acquis de l’Expérience[7]).

Higher education in France is divided between grandes écoles and public universities. The grandes écoles admit the graduates of the level Baccalauréat + 2 years of validated study (or sometimes directly after the Baccalauréat) whereas universities admit all graduates of the Baccalauréat.

A striking trait of French higher education, compared with other countries, is the small size and multiplicity of establishments, each specialized in a more-or-less broad spectrum of areas. A middle-sized French city, such as Grenoble or Nancy, may have 2 or 3 universities (focused on science or sociological studies) and also a number of engineering and other establishments specialized higher education. In Paris and its suburbs there are 13 universities, none of which is specialized in one area or another, and a large number of smaller institutions that are highly specialised.

It is not uncommon for graduate teaching programmes (master's degrees, the course part of PhD programmes etc.) to be operated in common by several institutions, allowing the institutions to present a larger variety of courses.

In engineering schools and the professional degrees of universities, a large share of the teaching staff is often made up of non-permanent professors; instead, part-time professors are hired to teach one only specific subject. The part-time professors are generally hired from neighbouring universities, research institutes or industries.

Another original feature of the French higher education system is that a large share of the scientific research is carried out by research establishments such as CNRS or INSERM, which are not formally part of the universities. However, in most cases, the research units of those establishments are located inside universities (or other higher education establishments) and jointly operated by the research establishment and the university.

Tuition costs

Since higher education is funded by the state, the fees are very low; the tuition varies from €150 to €700 depending on the university and the different levels of education. (licence, master, doctorate). One can therefore get a master's degree (in 5 years) for about €750-3,500. Additionally, students from low-income families can apply for scholarships, paying nominal sums for tuition or textbooks, and can receive a monthly stipend of up to €450 per month.

The tuition in public engineering schools is comparable to universities, albeit a little higher (around €700). However it can reach €7000 a year for private engineering schools, and some business schools, which are all private or partially private, charge up to €15000 a year.

Health insurance for students is free until the age of 20 so only the costs of living and books have to be added. After the age of 20, the health insurance for students costs €200 a year and cover most of the medical expenses.

Some public schools have other ways of gaining money. Some do not receive sufficient funds from the government for class trips and other extra activities and so these schools may ask for a small (optional) entrance fee for new students.

Universities in France

The public universities in France are named after the major cities near which they are located, followed by a numeral if there are several. Paris, for example, has thirteen universities, labelled Paris I to XIII. Some of these are not in Paris itself, but in the suburbs. In addition, most of the universities have taken a more informal name which is usually that of a famous person or a particular place. Sometimes, it is also a way to honor a famous alumnus, for example the science university in Strasbourg is known as "Université Louis Pasteur" while its official name is "Université Strasbourg I" (however, since 2009, the three universities of Strasbourg have been merged).

The French system has undergone a reform, the Bologna process, which aims at creating European standards for university studies, most notably a similar time-frame everywhere, with three years devoted to the bachelor's degree ("licence" in French), two for the Master's, and three for the doctorate. French universities have also adopted the ECTS credit system (for example, a licence is worth 180 credits). However the traditional curriculum based on end of semester examinations still remains in place in most universities. This double standard has added complexity to a system which also remains quite rigid. It is difficult to change a major during undergraduate studies without losing a semester or even a whole year. Students usually also have few course selection options once they enroll in a particular diploma.

France also hosts various branch colleges of foreign universities. These include Baruch College, the University of London Institute in Paris, Parsons Paris School of Art and Design and the American University of Paris.

Grandes écoles

The grandes écoles of France are elite higher-education establishments. They are generally focused on a single subject area (e.g., engineering or business), have a small size (typically between 100 and 300 graduates per year), and are highly selective. They are widely regarded as prestigious,[8][9] and most of France's scientists and executives have graduated from a grande école.

National rankings are published every year by various magazines.[10][11][12][13] While these rankings slightly vary from year to year, the top grandes écoles have been very stable for decades:

- science and engineering: Ecole Normale Supérieure, Ecole Polytechnique, Mines ParisTech, and CentraleSupélec;

- humanities: three Écoles Normales Supérieures and Ecole des Chartes;

- business: HEC Paris, ESSEC Business School, ESCP Europe, EMLyon and EDHEC;[14]

- administration and political sciences: ENA and Sciences Po.

Preparatory classes (CPGEs)

The Preparatory classes (in French "classes préparatoires aux grandes écoles" or CPGE), widely known as prépas, is a prep course with the main goal of training students for enrollment in a grande école. Admission to CPGEs is based on performance during the last two years of high school, called Première and Terminale. Only 5% of a generation is admitted to a prépa. CPGEs are usually located within high schools but pertain to tertiary education, which means that each student must have successfully passed their Baccalauréat (or equivalent) to be admitted in a CPGE. Each CPGE receives applications from hundreds of applicants worldwide every year in April and May, and selects students based on its own criteria. A few CPGEs, mainly the private ones (which account for 10% of CPGEs), also have an interview process or look at a student's involvement in the community.

The ratio of CPGE students who fail to enter any grande école is lower in scientific and business CPGEs than in humanities CPGEs.

Scientific CPGEs

The oldest CPGEs are the scientific ones, which can only be accessed by scientific Bacheliers. Scientific CPGE are called TSI ("Technology and Engineering Science"), MPSI ("Mathematics, Physics and Engineering Science"), PCSI ("Physics, Chemistry, and Engineering Science") or PTSI ("Physics, Technology, and Engineering Science") in the first year, MP ("Mathematics and Physics"), PSI ("Physics and Engineering Science"), PC ("Physics and Chemistry") or PT ("Physics and Technology") in the second year and BCPST ("Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Life and Earth Sciences").

First year CPGE students are called the "Math Sup"—or Hypotaupe—(Sup for "Classe de Mathématiques Supérieures", superior in French, meaning post-high school), and second years "Math Spé"—or Taupe—(Spés standing for "Classe de Mathématiques Spéciales", special in French). The students of these classes are called Taupins. Both the first and second year programmes include as much as sixteen hours of mathematics teaching per week, ten hours of physics, two hours of philosophy, two to four hours of (one or two) foreign languages teaching and two to three hours of minor options: either SI, Engineering Industrial Science or Theoretical Computer Science (including some programming using the Pascal or CaML programming languages, as a practical work). With this is added several hours of homework, which can rise as much as the official hours of class. A known joke among those students is that they are becoming moles for two years, sometimes three. This is actually the origin of the nicknames taupe and taupin (taupe being the French word for a mole).

Business CPGEs

There are also CPGE which are focused on economics (who prepare the admission in business schools). These are known as "Prépa EC" (short for Economiques et Commerciales) and are divided into two parts ("prépa EC spe mathematics", generally for those who graduated the scientific baccalaureat and "prépa EC spe éco", for those who were in the economics section in high school).

Humanities CPGEs (Hypokhâgne and Khâgne)

The literary and humanities CPGEs have also their own nicknames, Hypokhâgne for the first year and Khâgne for the second year. The students are called the khâgneux. These classes prepare for schools such as the three Écoles Normales Supérieures, the Ecole des Chartes, and sometimes Sciences Po.

There are two kinds of Khâgnes. The Khâgne de Lettres is the most common, and focuses on philosophy, French literature, history and languages. The Khâgne de Lettres et Sciences Sociales (Literature and Social Sciences), otherwise called Khâgne B/L, also includes mathematics and socio-economic sciences in addition to those literary subjects.

The students of Hypokhâgne and Khâgne (the humanities CPGE) are simultaneously enrolled in universities, and can go back to university in case of failure or if they feel unable to pass the highly competitive entrance examinations for the Écoles Normales Supérieures.

Colles

The amount of work required of the students is exceptionally high. In addition to class time and homework, students spend several hours each week completing exams called colles (sometimes written 'khôlles' to look like a Greek word, this way of writing being initially a khâgneux's joke). The colles are unique to French academic education in CPGEs.

In scientific and business CPGEs, colles consist of oral examinations twice a week, in French, foreign languages (usually English, German, or Spanish), maths, physics, philosophy, or geopolitics — depending on the type of CPGE. Students, usually in groups of three or four, spend an hour facing a professor alone in a room, answering questions and solving problems.

In humanities CPGEs, colles are usually taken every quarter in every subject. Students have one hour to prepare a short presentation that takes the form of a French-style dissertation (a methodologically codified essay, typically structured in 3 parts: thesis, counter-thesis, and synthesis) in history, philosophy, etc. on a given topic, or the form of a commentaire composé (a methodologically codified commentary) in literature and foreign languages. In Ancient Greek or Latin, they involve a translation and a commentary. The student then has 20 minutes to present his/her work to the teacher, who finally asks some questions on the presentation and on the corresponding topic.

Colles are regarded as very stressful, particularly due to the high standards expected by the teachers, and the subsequent harshness that may be directed at students who do not perform adequately. But they are important insofar as they prepare the students, from the very first year, for the oral part of the highly competitive examinations, which are reserved for the happy few who successfully pass the written part.

Recruitment of teachers

Decades ago, primary school teachers were educated in Ecoles Normales and secondary teachers recruited through the "Agrégation" examination. The situation has been diversified by the introduction in the 1950s of the CAPES examination for secondary teachers and in the 1990s by the institution of "Instituts Universitaires de Formation des Maîtres" (IUFM), which have recently been renamed Écoles Supérieures du Professorat et de l’Éducation (ESPE). University teachers are recruited by special commissions, and are divided between:

- "teachers-researchers" (enseignants-chercheurs), with at least a doctorate: they teach classes and conduct research in their field of expertise with a full tenure. They are either Maître de Conférences (Senior lecturers), or Professeurs (Professors). Only a Professor can be the director of studies for a PhD student. The net pay is from 2300 to 8800 (with extra duties) euros per month. Net salaries of over 4000 euros per month (2011 level) are however very unusual, and limited to the small minority of teacher-researchers who have held the grade of first class full professor for at least seven years, which is rare. The maximum possible net salary for second-class full professors and chief senior lecturers (maître de conférence hors classe)—the end of career status for most full-time teacher-researchers in French universities—is 3760 Euros a month (2011)—and only a minority of this group ever reach this level.

- Secondary school teachers who have been permanently assigned away from their original school position to teach in a university. They are not required to conduct any research but teach twice as many hours as the "teachers-researchers". They are called PRAG (professeurs agrégés) and PRCE (professeurs certifiés). Their weekly service is 15 or 18 hours. The net pay is from 1400 to 3900 euros per month.

- CPGE teachers are usually "agrégés" or "chaire sup", assigned by the Inspection Général according to their qualifications and competitive exam rank as well as other factors. Their weekly service is about 9 hours a week, 25 or 33 weeks a year. Net pay : from 2000 to 7500 euro (extra hours)

- Primary school and kindergarten teachers (Professeurs des écoles), educated in "Instituts Universitaires de Formation des Maîtres" (IUFM), have usually a "master" (Bac+5). Their weekly service is about 28 hours a week.

Religion

Religious instruction is not given by public schools (except for 6- to 18-year-old students in Alsace-Lorraine under the Concordat of 1801). Laïcité (secularism) is one of the main precepts of the French republic.

In a March 2004 ruling, the French government banned all "conspicuous religious symbols" from schools and other public institutions with the intent of preventing proselytisation and to foster a sense of tolerance among ethnic groups. Some religious groups showed their opposition, saying the law hindered the freedom of religion as protected by the French constitution.

Statistics

The French Republic has 67 million inhabitants, living in the 13 regions of metropolitan France and four overseas departments (2.7 million). Despite the fact that the population is growing (up 0.4% a year), the proportion of young people under 25 is falling. There are now fewer than 19 mill young people in metropolitan France, or 32% of the total population, compared with 40% in the 1970s and 35% at the time of the 190 census. France is seeing a slow aging of the population—less marked however than in other neighbouring countries (such as Germany and Italy), especially as the annual number of births is currently increasing slightly.

Eighteen million pupils and students, i.e. a quarter of the population, are in the education system. Of these, over 24 million are in higher education.[15] The French Education Minister reported in 2000 that 39 out of 75,000 state schools were "seriously violent" and 300 were "somewhat violent".[16]

See so

- Agency for French Teaching Abroad (Agence pour l'enseignement français à l'étranger)

- Campus France (Agency for the promotion of French Higher Education)

- Conférence des Grandes Écoles (CGE)

- Commission des Titres d'Ingénieur

- Comité d'études sur les formations d'ingénieurs

- Conference of the Directors of French Engineering Schools (Conférence des directeurs des écoles françaises d'ingénieurs (CDEFI))

- Homeschooling in France

References

- ↑ "Le Bulletin officiel". Ministère de l'Éducation nationale, de l'Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche.

- ↑ "International School Consultancy Group > Home". Iscresearch.com. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- 1 2 "International School Consultancy Group > Information > ISC News". Iscresearch.com. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- ↑ "The new local". The Economist. 17 December 2014.

- 1 2 "La Licence". enseignementsup-recherche.gouv.fr (in French). 2016-07-19. Retrieved 2016-07-19.

- 1 2 "Le Master". enseignementsup-recherche.gouv.fr (in French). 2016-07-19. Retrieved 2016-07-19.

- ↑ "Validation des acquis de l'expérience (VAE)". Vosdroits.service-public.fr (in French). 2011-05-02. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- ↑ Understanding the "Grandes Ecoles", retrieved 2009-06-07

- ↑ "grande école". French to English translation by CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved November 02, 2012.

- ↑ L'Étudiant, Palmarès des grandes écoles de commerce.

- ↑ L'Étudiant, Palmarès des écoles d'ingénieurs.

- ↑ Le Figaro, Classement des écoles de commerce.

- ↑ L'Usine nouvelle, Palmarès des écoles d'ingénieurs.

- ↑ "Classement SIGEM des écoles de commerce | Bloom6". bloom6.free.fr. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ Kabla-Langlois, Isabelle; Dauphin, Laurence (2015). "Students in higher education". Higher education & research in France, facts and figures - 49 indicators. Paris: Ministère de l'Éducation nationale, de l'Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ Lichfield, J. (2000, January 27). Violence in the lycees leaves France reeling. The Independent. London.

External links

- Eurydice France, Eurydice: Portal for European education systems

- French Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research (English)

- School Education in France, Eduscol: the French portal for Education players (English)

- Education in France, a webdossier by the German Education Server (English)