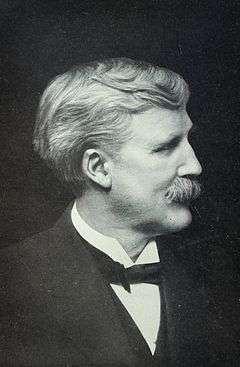

Frederick Taylor Gates

Frederick Taylor Gates (1853–1929) was an American Baptist clergyman, educator, and the principal business and philanthropic advisor to the major oil industrialist and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Sr., from 1891 to 1923.

Early life

Frederick Taylor Gates, son of Granville and Sarah Jane (Bowers) Gates, was born 2 July 1853 in Maine, Broome County, New York. Granville was a Baptist minister. Frederick's neighbor and uncle was Cyrus Gates a cartographer, abolitionist and local judge. He graduated from the University of Rochester in 1877 and from the Rochester Theological Seminary in 1880. From 1880 to 1888, he served as pastor of the Central Baptist Church in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He left the ministry and was appointed the secretary of the newly formed American Baptist Education Society where he championed a Baptist university in Chicago to fill a void that existed in Baptist education.

Rockefeller adviser

On January 21, 1889, Gates met the lifetime Baptist, John D. Rockefeller, Sr. He proved to be central to the suggestion and subsequent design of the funding plans for the creation by Rockefeller, Sr. of the Baptist University of Chicago; he subsequently served for many years as a trustee on its board.

Standard Oil

Gates then became Rockefeller's key philanthropic and business adviser, working in the newly established family office in Standard Oil headquarters at 26 Broadway, where he oversaw Rockefeller's investments in a series of investments in many companies but not in his personal stock in the Standard Oil Trust.

From 1892 onwards, faced with his ever expanding investments and real estate holdings, Rockefeller Sr. recognized the need for professional advice and so he formed a four-member committee, later including his son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to manage his money, and nominated Gates as its head and as his senior business adviser. In this capacity Gates steered Rockefeller Sr. money predominantly to syndicates arranged by the investment house of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., and, to a lesser extent, the house of J. P. Morgan.[1]

Other roles

Gates served on the boards of many companies in which Rockefeller had a majority shareholding; the latter then held a securities portfolio of unprecedented size for a private individual. Although Gates is recognized today as a philanthropic advisor, Rockefeller himself regarded him as the greatest businessman he had encountered in his life, skipping such prominent figures of the time as Henry Ford and Andrew Carnegie.[2]

When he ceased being a business advisor to Rockefeller in 1912, Gates continued to advise him and his son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., on philanthropic matters, at the same time serving on many corporate boards. He also served as president of the General Education Board, which was subsequently merged into other Rockefeller family institutions.

Philanthropy

Gates focused exclusively on philanthropy after 1912. He moved Rockefeller from doling out retail sums to specific recipients to the wholesale process of setting up well-funded foundations that were run by experts who decided what topics of reform were ripe. In all Gates supervised the distribution of about $500 million. Although Rockefeller himself believed in folk medicine, the billionaire listened to his experts, and Gates convinced him that he could have the greatest impact by modernizing medicine especially by reforming education, sponsoring research to identify cures, and systematically eradicating debilitating diseases that sapped national efficiency like hookworm.

In 1901, Gates designed the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (now Rockefeller University), of which he was board president. He then designed the Rockefeller Foundation, becoming a trustee upon its creation in 1913. Gates served as president of the General Education Board, which became the leading foundation in the field of education.

By 1912, however, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. was taking control of philanthropic policies, with Gates slipping to second place. Although Gates never quite lost his religion,[3] he began shifting the direction from religious charities to decidedly more secular pursuits like medical research and education. Gates designed the China Medical Board (CMB) in 1914. Rather than viewing China through the traditional missionary lens of millions of heathens to be converted, Gates placed his faith in science. He complained the missionaries in China were trapped in the "bondage of tradition and an ignorance and misguided sentiment in the supporting churches."[4] They had made few converts and fumbled the opportunity to spread Western science. There were hundreds of medical missionaries but they linked Western medical "miracles" to the teachings of Christianity. Instead of focusing on preventive health, they urged sick and dying patients to convert. Gates planned to take over the Peking Union Medical College and retrain missionaries there.Working at the intersection of philanthropy, imperialism, big business, religion, and science, the China Medical Board was his last major project.

In 1924, Gates overreached, asking the Rockefeller Foundation Board to invest $265 million in the China Medical Board. The fantastic sum would make Chinese medical care the finest in the world and would eliminate denominationalism influence from the practice of medicine and charity work in China. The Board refused and Gates became a victim of his own progressive emphasis on the "rule of experts." The experts on China and medicine disagreed with him, and he was marginalized, causing his resignation from the CMB.[5]

Gates was a progressive and committed to the Efficiency Movement. He looked for leverage whereby a few millions of dollars would generate significant changes, as in the creation of a new university, the eradication of hookworm because it reduced efficiency or the revolution in hospitals caused by the Flexner Report.[6]

Bibliography

- Baick, John S. "Cracks in the Foundation: Frederick T. Gates, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the China Medical Board." Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 2004 3(1): 59-89. ISSN 1537-7814 Fulltext: at History Cooperative, the most useful analysis

- Berliner, Howard S. A System of Scientific Medicine: Philanthropic Foundations in the Flexner Era. Tavistock, 1985. 190 pp.

- Brown, E. Richard Rockefeller Medicine Men: Medicine and Capitalism in America (1979), sees Rockefeller philanthropy as bad because it reflected Western imperialism

- Chernow, Ron, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., 1998.

- Gates, Frederick Taylor. Chapters in my Life. 1977. autobiography

- General Education Board The General Education Board: An Account of Its Activities, 1902-1914 (1915).

- Nevins, Allan, Study in Power: John D. Rockefeller, Industrialist and Philanthropist. 2 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1953.

- Ninkovich, Frank. "The Rockefeller Foundation, China, and Cultural Change," Journal of American History 70 (March 1984): 799-820. in JSTOR

- Starr, Harris Elwood, "Frederick T. Gates" in Dictionary of American Biography, Volume 4 (1931).

See also

Notes and references

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "article name needed". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "article name needed". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ↑ Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. London: Warner Books, 1998. (pp.372-73)

- ↑ Greatest businessman Rockefeller had encountered - Ibid., (p.370)

- ↑ But he says he felt no "deep sense of guilt... and little fear of hell." Gates (1977) p. 49

- ↑ Quoted in Baick (2004)

- ↑ Baick (2004)

- ↑ Berliner (1985)