Max Brand

| Max Brand | |

|---|---|

|

Max Brand | |

| Born |

Frederick Schiller Faust May 29, 1892 Seattle, Washington, United States |

| Died |

May 12, 1944 (aged 51) Italy |

| Resting place | United States |

| Pen name |

Max Brand George Owen Baxter Evan Evans George Evans David Manning John Frederick Peter Morland George Challis Peter Ward Frederick Frost |

| Occupation | Writer, author |

| Genre | Western |

| Spouse | Dorothy Schillig |

| Relatives |

Gilbert Leander Faust (father) Louisa Elizabeth (Uriel) Faust (mother) |

Frederick Schiller Faust (May 29, 1892 – May 12, 1944) was an American author known primarily for his thoughtful and literary Westerns under the pen name Max Brand. Faust (as Max Brand) also created the popular fictional character of young medical intern Dr. James Kildare in a series of pulp fiction stories.[1] Faust's Kildare character was subsequently featured over several decades in other media, including a series of American theatrical films by Paramount Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM),[2] a radio series,[3] two television series,[4][5] and comics.[6][7] Faust's other pseudonyms include George Owen Baxter, Evan Evans, George Evans, David Manning, John Frederick, Peter Morland, George Challis, Peter Ward and Frederick Frost.

Biography

Faust was born in Seattle to Gilbert Leander Faust and Louisa Elizabeth (Uriel) Faust, both of whom died when Faust was still a boy. He grew up in central California, and later worked as a cowhand on one of the many ranches of the San Joaquin Valley. Faust attended the University of California, Berkeley, where he began to write for student publications, poetry magazines, and newspapers. Failing to graduate, Faust joined the Canadian Army in 1915, but deserted the next year and moved to New York City.

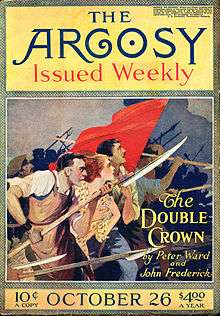

During the 1910s, Faust sold stories to the pulp magazines of Frank Munsey, including All-Story Weekly and Argosy Magazine. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Faust tried to enlist but was rejected. He married Dorothy Schillig in 1917, and the couple had three children.

In the 1920s, Faust wrote extensively for pulp magazines, especially Street & Smith’s Western Story Magazine, a weekly for which he would write over a million words a year under various pen names, often seeing two serials and a short novel published in a single issue. In 1921, he suffered a severe heart attack, and for the rest of his life suffered from chronic heart disease.

His love for mythology was a constant source of inspiration for his fiction, and it has been speculated that these classical influences accounted in some part for his success as a popular writer. Many of his stories would later inspire films. He created the Western character Destry, featured in several cinematic versions of Destry Rides Again, and his character Dr. Kildare was adapted to motion pictures, radio, television, and comic books.

In 1934 Faust began to write for upscale, slick magazines, often writing from a villa in Italy. In 1938, due to political events in Europe, he returned with his family to the United States and settled in Hollywood where he worked as a screenwriter for a number of film studios. At one point, Warner Brothers paid him $3,000 a week (a year’s salary for an average worker at the time), and he made a fortune from MGM’s Dr. Kildare adaptations. Faust became one of the highest paid writers of his day. Ironically, Faust disparaged his commercial success and used his real name only for the poetry that he regarded as his literary calling.

In 1943, author Frank Gruber met Faust and wrote about him in his book The Pulp Jungle (1967). Faust he said was six feet three inches tall and weighed about 200 lbs (of which there was not an ounce of fat) and had enormous hands. He was shy and somewhat aloof. He liked to be called "Heinie" by friends and he was an alcoholic. Amongst other drinks, he put away two quarts of whiskey during an eight-hour day. When he went home at five thirty, he had a light supper then got down to "some serious drinking". Faust maintained that the alcohol transported him away to a fantasy world where he could write. He was never "drunk" and was open about his drinking.

Faust had trained himself to write exactly 14 pages of work a day, every day. That added up to a million and a half words a year, for thirty years. Faust's work was all about "originals". He never mastered the technique of adapting an original into a screenplay, which was written by others. Faust wrote under 15 pseudonyms in all. He told Gruber that though he had written 300 books, they all had the same plot: The good man becomes bad and the bad man becomes good.

In early 1944, when Faust, Gruber, and fellow author Steve Fisher were working at Warner Brothers, they had "bull" sessions in the afternoons, along with Colonel Nee, who was a technical advisor sent from Washington DC. Amply charged with whiskey, Faust talked of getting assigned to a company of foot soldiers so he could experience the war and later write a great war novel. Colonel Nee said he could fix it for him and some weeks later he did, getting Faust an assignment for Harper's Magazine as a war correspondent in Italy. While traveling with American soldiers fighting in Italy in 1944, Faust was mortally wounded by shrapnel.[8][9] He was personally commended for bravery by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Works

- Harrigan (1918)

- Riders of the Silence (1919)

- The Untamed (1919).

- The Night Horseman (1920)

- Ronicky Doone (1921)

- The Seventh Man (1921)

- Alcatraz (1922)

- Black Jack (1922)

- The Rangeland Avenger (1922)

The Gunmans Reckoning

Legacy

Faust rivalled Edgar Wallace and Isaac Asimov as one of the most prolific authors of all time. He wrote more than 500 novels for magazines and almost as many shorter stories. His total literary output is estimated to have been between 25,000,000 and 30,000,000 words. Most of his books and stories were produced at a breakneck pace, which sometimes amounted to 12,000 words in one weekend. New books based on magazine serials or previously unpublished works authored by him continue to appear, so that Faust has averaged a new book every four months for seventy-five years. Moreover, some work by him is reprinted every week each year, in one format or another, somewhere in the world.

References

- ↑ "Dr. Kildare - NBC (ended 1966)" (entry at TV.com database for 1960s "Dr. Kildare" TV series), accessed Mar. 28, 2015.

- ↑ Mavis, Paul. "Dr. Kildare Movie Collection (Warner Archive Collection)" (DVD review). DVDtalk.com, Mar. 16, 2014, accessed Mar. 29, 2015.

- ↑ The Digital Deli Online, "The Story of Dr. Kildare (Radio Program)." Archived 2014-03-27 at the Wayback Machine. digitaldeliftp.com, accessed Mar. 29, 2015.

- ↑ Mcneil, Alex. Total Television: The Comprehensive Guide to Programming from 1948 to the Present - Revised Edition. Penguin Books, 1996, p. 225. ISBN 978-0140249163.

- ↑ "Young Dr. Kildare" overview, TVguide.com, accessed Mar. 29, 2015.

- ↑ Polite Dissent (blog), "The Brief 'Golden Age of Medical Comics'," politedissent.com, May 28, 2012, accessed March 29, 2015.

- ↑ The Archivist, "Ask the Archivist: Calling Dr. Kildare." The Comics Kingdom Blog, comicskingdom.com, October 24, 2012, accessed March 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Kildare Creator Is Killed In Italy," by Milton Bracker, The New York Times, May 17, 1944.

- ↑ "A Farewell To Max Brand," by Steve Fisher, published simultaneously in Argosy and Writer's Digest, in their August 1944 issues.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Max Brand |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Max Brand official website

- Guide to the Frederick Schiller Faust Papers at The Bancroft Library

- Works by Max Brand at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Max Brand at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Frederick Schiller Faust at Internet Archive

- Works by Frederick Schiller Faust at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by Max Brand at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)