Junípero Serra

| Saint Junípero Serra, O.F.M. | |

|---|---|

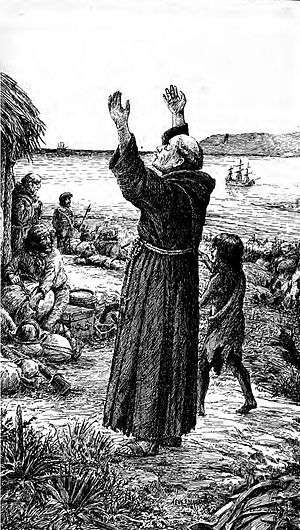

A portrait of Serra in 1774 | |

| Apostle of California | |

| Born |

Miquel Josep Serra i Ferrer November 24, 1713 Petra, Majorca |

| Died |

August 28, 1784 Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, Las Californias, New Spain, Spanish Empire |

| Beatified | 25 September 1988, Saint Peter's Square by Pope John Paul II |

| Canonized | 23 September 2015, Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception by Pope Francis |

| Major shrine | Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, United States |

| Attributes | Franciscan habit, wearing a large crucifix, or holding a crucifix accompanied by a young Native American boy |

| Patronage |

|

| Controversy | Suppression of Native American culture |

Junípero Serra y Ferrer, O.F.M., (/huːˈnɪpɛroʊ ˈsɛrə/; Spanish: [xuˈnipeɾo ˈsera], Catalan: Juníper Serra i Ferrer) (November 24, 1713 – August 28, 1784) was a Roman Catholic Spanish priest and friar of the Franciscan Order who founded a mission in Baja California and the first nine of 21 Spanish missions in California from San Diego to San Francisco, in what was then Alta California in the Province of Las Californias, New Spain. Serra was beatified by Pope John Paul II on September 25, 1988, in Vatican City. Pope Francis canonised him on September 23, 2015, at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., during his first visit to the United States.[3] Because of Serra's recorded acts of piety combined with his missionary efforts, he was granted the posthumous title Apostle of California.

The declaration of Serra as a Catholic saint by the Holy See is controversial with some Native Americans who criticize Serra's treatment of their ancestors and associate him with the suppression of their culture.[4]

Early life

Serra (born Miquel Josep Serra, November 24, 1713 – August 28, 1784) was born in the village of Petra on the island of Majorca (Mallorca) off the Mediterranean coast of Spain. A few hours after birth, he was baptized in the village church. His baptismal name was Miquel Joseph Serra.[5] His father Antonio Nadal Serra and mother Margarita Rosa Ferrer were married in 1707.[6]

By age seven, Miquel was working the fields with his parents, helping cultivate wheat and beans, and tending the cattle. But he showed a special interest in visiting the local Franciscan friary at the church of San Bernardino within a block of the Serra family house. Attending the friars' primary school at the church, Miquel learned reading, writing, mathematics, Latin, religion and liturgical song, especially Gregorian chant. Gifted with a good voice, he eagerly took to vocal music. The friars sometimes let him join the community choir and sing at special church feasts. Miquel and his father Antonio often visited the friary for friendly chats with the Franciscans.[7]

At age 15, Miquel's parents enrolled him in a Franciscan school in the capital city, Palma de Majorca, where he studied philosophy. A year later, he became a novice in the Franciscan order.

Joins Franciscan order

On November 14, 1730—just shy of his 17th birthday—Serra entered the Alcantarine branch of the Friars Minor, a reform movement in the Order. The slight and frail Serra now embarked on his novitiate period, a rigorous year of preparation to become a full member of the Franciscan Order. He was given the religious name of Junípero in honor of Brother Juniper, who had been among the first Franciscans and was a companion of Saint Francis.[8] The young Junípero, along with his fellow novices, vowed to scorn property and comfort, and to remain celibate. He still had seven years to go to become an ordained Catholic priest. He immersed himself in rigorous studies of logic, metaphysics, cosmology, and theology.

The daily routine at the friary followed a rigid schedule: prayers, meditation, choir singing, physical chores, spiritual readings, and instruction. The friars would wake up every midnight for another round of chants. Serra's superiors discouraged letters and visitors.[9] In his free time, he avidly read stories about Franciscan friars roaming the provinces of Spain and around the world to win new souls for the church, often suffering martyrdom in the process. He followed the news of famous missionaries winning beatification and sainthood.

In 1737, Serra became a priest, and three years later earned an ecclesiastical license to teach philosophy at the Convento de San Francisco. His philosophy course, including over 60 students, lasted three years. Among his students were fellow future missionaries Francisco Palóu and Juan Crespí.[10] When the course ended in 1743, Serra told his students: "I desire nothing more from you than this, that when the news of my death shall have reached your ears, I ask you to say for the benefit of my soul: 'May he rest in peace.' Nor shall I omit to do the same for you so that all of us will attain the goal for which we have been created."[11]

Serra was considered intellectually brilliant by his peers. He received a doctorate in theology from the Lullian College (founded in the 14th century by Ramon Lull for the training of Franciscan missionaries) in Palma de Majorca, where he also occupied the Duns Scotus chair of philosophy until he joined the missionary College of San Fernando de Mexico in 1749.[12]

During Serra's last five years on the island of Majorca, drought and plague afflicted his home village of Petra. Serra sometimes went home from Palma for brief visits to his parents—now separated—and gave them some financial support. On one occasion he was called home to anoint his seriously ill father with the last rites. In one of his final visits to Petra, Serra found his younger sister Juana María near death.[13]

In 1748, Serra and Palóu confided to each other their desire to become missionaries. Serra, now 35, was assured a prestigious career as priest and scholar if he stayed in Majorca; but he set his sights firmly on pagan lands. Applying to the colonial bureaucracy in Madrid, Serra requested that both he and Palóu embark on a foreign mission. After weathering some administrative obstacles, they received permission and set sail for Cádiz, the port of departure for Spain's colonies in the Americas.

While waiting to set sail, Serra wrote a long letter to a colleague back in Majorca, urging him to console Serra's parents—now in their 70's—over their only son's pending departure. "They [my parents] will learn to see how sweet is His yoke," Serra wrote, "and that He will change for them the sorrow they may now experience into great happiness. Now is not the time to muse or fret over the happenings of life but rather to be conformed entirely to the will of God, striving to prepare themselves for that happy death which of all the things of life is our principal concern."[14] Serra asked his colleague to read this letter to his parents, who had never attended school.[15]

Ministry in the Americas

In 1749, Serra and the Franciscan missionary team landed in Veracruz, on the Gulf coast of New Spain (now Mexico). To get from Veracruz to Mexico City, Serra and his Franciscan companions took the Camino Real (English: royal path), a rough road stretching from sea level through tropical forests, dry plains, high plateaus and volcanic sierra mountains to an altitude of 7400 feet (2250 meters). Royal officials provided horses for the 20 Franciscan friars to ride up the Camino Real. All accepted the offer, except for Serra and one companion, a friar from Andalusia. Strictly following the rule of his patron saint Francis of Assisi that friars "must not ride on horseback unless compelled by manifest necessity or infirmity," Serra insisted on walking to Mexico City. He and his fellow friar set out on the Camino Real with no money or guide, carrying only their breviaries. They trusted in Providence and the hospitality of local people along the way.

During the trek Serra's left foot swelled up, and a burning itch tormented him. Arriving at a farm at day's end, he could hardly stand. He attributed the swelling to a mosquito bite. His discomfort made his stay over at the farm another night, during which he scratched his foot and leg to excess, desperately trying to relieve the itch. The next morning his leg was raw and bleeding. This wound plagued Serra for the rest of his life.[16]

Hobbling into Mexico City, Serra joined up with his fellow friars at the College of San Fernando de Mexico, a specialized training center and regional headquarters for Franciscan missionaries. Serra requested that he do his novitiate year again—despite his academic prestige, and the fact that the college's novices were far younger men. Though his request was declined, Serra insisted on living as a novice at San Fernando: "This learned university professor…would often eat more sparingly in order to replace the student whose turn it was to read to the community. Or he would humbly carry trays and wait on tables with the lay brothers…"[17]

Besides the routine of prayers, hymns and meditations, daily life at the secluded college included classes on the languages of Mexico's Indian peoples, mission administration and theology. Before completing his required year of training, Serra volunteered for a mission in the rugged Sierra Gorda, to help replace friars who had recently died there. He was accepted as mission superior. His fellow volunteer, Friar Francisco Palóu, became Serra's assistant in his first mission.

Mission in the Sierra Gorda, Mexico

The Sierra Gorda Indian missions, some 90 miles north of Santiago de Querétaro, were nestled in a vast region of jagged mountains, home of the Pame Indians and a scattering of Spanish colonists. The Pames—who, centuries earlier, had built a civilization with temples, idols and priests—lived mainly by gathering and hunting, but also pursued agriculture. Many groups among them, adopting mobile guerrilla tactics, had eluded conquest by the Spanish military.

Serra and Palóu, arriving at the village of Jalpan, found the mission in disarray: The parishioners, numbering fewer than a thousand, were attending neither confession nor Mass.[18] The two missionaries set about learning the Pame language from a Mexican who had lived among the Pames. But the claim by Palóu that Serra translated the catechism into the Pame language is questionable, as Serra himself later admitted he had great difficulties learning indigenous languages.[19]

Serra involved Pames parishioners in the ritual reenactment of Jesus' forced death march. Erecting 14 stations, Serra led the procession himself, carrying an extremely heavy cross. At each station, the procession paused for a prayer, and at the end Serra sermonized on the sufferings and death of Jesus. On Holy Thursday, 12 Pames elders reenacted the roles of the apostles. Serra, in the role of Jesus, washed their feet and then, after the service, dined with them.[20]

Serra also tackled the practical side of mission administration. Working with the college of San Fernando, he had cattle, goats, sheep, and farming tools brought to the Sierra Gorda mission. Palóu supervised the farm labor of mission Indian men; the women learned spinning, sewing and knitting. Their products were collected and rationed to the mission residents, according to personal needs. Christian Pames sold their surplus products in nearby trading centers, under the friars' supervision to protect them from cheaters. Pames who adapted successfully to mission life received their own parcels of land to raise corn, beans and pumpkins, and sometimes received oxen and seeds as well.[21]

Within two years, Serra had made inroads against the Pames' traditional belief system. On his 1752 visit from the Sierra Gorda mission to the college of San Fernando in Mexico City, Serra joyfully carried a goddess statue presented to him by Christian Pames. The statue, showing the face of Cachum, mother of the sun, had been erected on a hilltop shrine where some Pame chiefs lay buried.[22]

Back in the Sierra Gorda, Serra faced a conflict between Spanish soldiers, settlers, and mission Indians. Following a Spanish military victory over the Pames in 1743, Spanish authorities had sent not only Franciscan missionaries, but also Spanish/Mexican soldiers and their families into the Sierra Gorda. The soldiers had the job of pursuing runaway mission Indians and securing the region for the Spanish crown. But the soldiers' land claims clashed with mission lands that Christian Pames were working.

Some of the soldiers' families tried to establish a town, and the officer in charge of their deployment approved their plan. The Pames objected, threatening to defend their lands by force if necessary. Soldiers and settlers let their cattle graze on Christian Pames' farmlands and bullied Pames into working for them. Serra and the College of San Fernando sided with the Pames—citing the Laws of the Indies, which banned colonial settlements in mission territories.

The viceroy, Spain's highest official in Mexico, suspended the intrusive colony. But the townspeople protested and stayed put. The government set up commissions and looked into alternative sites for the colony. It ordered the settlers to keep their cattle out of the Pames' fields, and to pay the Pames fairly for their labor (with the friars supervising payment). After a protracted legal struggle, the settlers moved out, and in 1755 the Pames and friars reclaimed their land.[23]

Crowning his Sierra Gorda mission, Serra oversaw the construction of a splendid church in Jalpan. Gathering masons, carpenters, and other skilled craftsmen from Mexico City, Serra employed Christian Pames in seasonal construction work over the course of seven years to complete the church. Serra pitched in himself, carrying wooden beams and applying mortar between the stones forming the church walls.[24]

Serra's work for the Inquisition

During his 1752 visit to Mexico City, Serra sent a request from the college of San Fernando to the local headquarters of the Spanish Inquisition. He asked that an inquisitor be appointed to preside over the Sierra Gorda. The next day, Inquisition officials appointed Serra himself as inquisitor for the whole region—adding that he could exercise his powers anywhere he did missionary work in New Spain, as long as there was no regular Inquisition official in the region.[25]

In September 1752, Serra filed a report to the Spanish Inquisition in Mexico City from Jalpan, on "evidences of witchcraft in the Sierra Gorda missions." He denounced several Christian non-Indians who lived in and around the mission for "the most detestable and horrible crimes of sorcery, witchcraft and devil worship… If it is necessary to specify one of the persons guilty of such crimes, I accuse by name a certain Melchora de los Reyes Acosta, a married mulattress, an inhabitant of the said mission… In these last days a certain Cayetana, a very clever Mexican woman of said mission, married to one Pérez, a mulatto, has confessed—she, being observed and accused of similar crimes, having been held under arrest by us for some days past—that in the mission there is a large congregation of [Christian non-Indians], although some Indians also join them, and that these persons,…flying through the air at night, are in the habit of meeting in a cave on a hill near a ranch called El Saucillo, in the center of said missions, where they worship and make sacrifice to the demons who appear visibly there in the guise of young goats and various other things of that nature… If such evil is not attacked, the horrible corruption will spread among these poor [Indian] neophytes who are in our charge."[26]

According to modern Franciscan historians, this report by Serra to the Inquisition is the only letter of his that has survived from eight years of mission work in the Sierra Gorda.[27] Serra's first biographer, Francisco Palóu, wrote that Serra, in his role of inquisitor, had to work in many parts of Mexico and travel long distances. Yet the Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico City, with over a thousand volumes of indexed documents on the Inquisition, apparently contains only two references to Serra's work for the Inquisition following his 1752 appointment: his preaching in Oaxaca in 1764, and his partial handling of the case of a Sierra Gorda mulatto accused of sorcery in 1766.[28][29]

In 1758, Serra returned to the College of San Fernando. Over the next nine years he worked in the college's administrative offices, and as a missionary and inquisitor in the dioceses of Mexico, Puebla, Oaxaca, Valladolid, and Guadalajara. In his missionary wanderings, Serra often kept traveling on foot, despite painful leg and foot sores.

Physical self-punishment

Emulating an earlier Franciscan missionary and saint, Francisco Solano, Serra made a habit of punishing himself physically, to purify his spirit. He wore a sackcloth spiked with bristles, or a coat interwoven with broken pieces of wire, under his gray friar's outer garment.[30] In his austere cell, Serra kept a chain of sharp pointed iron links hanging on the wall beside his bed, to whip himself at night when sinful thoughts ran through his mind. His nightly self-flagellations at the college of San Fernando caught the ears of some of his fellow friars. In his letters to his Franciscan companions, Serra often referred to himself as a "sinner" and a "most unworthy priest."

In one of his sermons in Mexico City, while exhorting his listeners to repent their sins, Serra took out his chain, bared his shoulders and started whipping himself. Many parishioners, roused by the spectacle, began sobbing. Finally, a man climbed to the pulpit, took the chain from Serra's hand and began whipping himself, declaring: "I am the sinner who is ungrateful to God who ought to do penance for my many sins, and not the padre [Serra], who is a saint." The man kept whipping himself until he collapsed. After receiving the last sacraments, he later died from the ordeal.[31]

During other sermons on the theme of repentance, Serra would hoist a large stone in one hand and, while clutching a crucifix in the other, smash the stone against his chest. Many of his listeners feared that he would strike himself dead. Later, Serra suffered chest pains and shortness of breath; Palóu suggests that Serra's self-inflicted bruises were the cause. While preaching of hell and damnation, Serra would sear his flesh with a four-pronged candle flame—emulating a famed Franciscan preacher, saint John of Capistrano.[32] Palóu described this as "quite violent, painful, and dangerous towards wounding his chest."[33]

Serra did not stand alone among Catholic missionaries in displaying self-punishment at the pulpit. The more zealous Franciscan and Jesuit missionaries did likewise. But few took it to the extremes that Serra did. The regulations of the college of San Fernando said that self-punishment should never be carried to the point of permanently incapacitating oneself.[34] Some of Serra's colleagues admonished him for going too far.

King Carlos expels the Jesuits

On June 24, 1767, the Viceroy of New Spain, Carlos Francisco de Croix, read a Spanish royal decree to Mexico's archbishop and assembled church officials: "Repair with an armed force to the houses of the Jesuits. Seize the persons of all of them and, within 24 hours, transport them as prisoners to the port of Veracruz. Cause to be sealed the records of said houses and records of such persons without allowing them to remove anything but their breviaries and such garments as are absolutely necessary for their journey. If after the embarkation there should be found one Jesuit in that district, even if ill or dying, you shall suffer the penalty of death."[35]

Spain's king Carlos III had plotted the expulsion of Jesuits throughout his empire five months earlier. Within days of his viceroy reading the expulsion decree to Mexico's top Catholic officials, Spanish royal soldiers removed the Jesuits—who offered no resistance—from all their stations within ready communication range of Mexico City. Many Jesuit priests died along the rugged mountain trail to Veracruz, where overloaded ships waited to carry the survivors across the Atlantic to the Papal States on the Italian peninsula.

On the Baja California peninsula, newly appointed governor Gaspar de Portolá had to notify and remove the Jesuits from the chain of missions they had developed in forbidding territory over 70 years. By February 1768, Portolá gathered the 16 Baja Jesuit missionaries in Loreto, from where they sailed to mainland Mexico for deportation. Sympathetic to the Jesuits, Portolá treated them kindly even as he removed them under the king's orders.[36]

President of Baja California missions

Into the vacuum created by the Jesuits' expulsion from Mexico, stepped Franciscan missionaries. In July 1767, the guardian of the college of San Fernando appointed Serra president of the missions of Baja California, heading a group of 15 Franciscan friars; Francisco Palóu served as his second in command.[37] Jesuit priests had developed 13 missions on that long and arid peninsula over seven decades. Two Jesuits had died at the hands of Indians in the revolt of 1734–6.

In March 1768, Serra and his missionary team boarded a Spanish sloop at San Blas, on Mexico's Pacific coast. Sailing over 200 miles up the Gulf of California, they landed at Loreto two weeks later. Gaspar de Portolá, governor of Las Californias, welcomed them at the Loreto mission, founded by Jesuits in 1697. While he gave control of the church to Serra, Portolá controlled the living quarters and rationed out food to the friars, charging their costs to the mission.[38]

Serra and Palóu found—to their unpleasant surprise—that they ruled only on spiritual matters: everyday management of the mission remained in the hands of the military, who had occupied the Baja missions since evicting the Jesuits. In August 1768, New Spain's inspector general José de Gálvez, displeased with the sloppy military administration of the Baja missions, ordered them turned over fully to the Franciscan friars.[39]

Serra started assigning his fellow friars to the missions scattered up the length of the Baja peninsula, with its scarce water and food sources. He stayed over a year at the Loreto mission while his colleagues tried to convert Indians in the nearby mountains and deserts. Where mission workers could dam small streams, they managed to grow wheat, corn, beans, fruits and cotton—always depending on the availability of water.

The Franciscans found that the Indian population in the Baja California mission territories had dwindled to about 7,150. By the time the Franciscans had moved north and turned the missions over to Dominican friars in 1772, the Indian population had decreased to about 5,000. "If it goes on at this rate," wrote Palóu, "in a short time Baja California will come to an end." Epidemics, especially syphilis introduced by Spanish troops, were wasting the Indians.[40] But Palóu attributed the ravages of syphilis to God's retribution for the Indians' murder of the two Jesuit priests over 30 years earlier.[41]

Journey to San Diego

In 1768 José de Gálvez, inspector general of New Spain, decided to send explorers and locate missions in Alta (upper) California. Gálvez aimed both to Christianize the extensive Indian populations and serve Spain's strategic interest by preventing Russian explorations and possible claims to North America's Pacific coast.[42] Gálvez chose Serra to head the missionary team in the California expedition. Serra, now 55, eagerly seized the chance to harvest thousands of pagan souls in lands previously untouched by the church.

But as the expedition gathered in Loreto, Serra's foot and leg infection had become almost crippling. The commander, Gaspar de Portolá, tried to dissuade him from joining the expedition, and wrote to Gálvez about Serra's condition. Serra's fellow friar and former student Francisco Palóu also became concerned, gently suggesting to Serra that he stay in Baja California and let the younger and stronger Palóu make the journey to San Diego in his place. Serra rebuffed both Portolá's and Palóu's doubts. He chided Palóu for his suggestion: "Let us not speak of that. I have placed all my confidence in God, of whose goodness I hope that He will grant me to reach not only San Diego to raise the standard of the Holy Cross in that port, but also Monterey."[43]

Serra suggested that the Portolá party set off without him; he would follow and meet up with them on the way to Alta California. He then assigned friar Miguel de la Campa as chaplain to the Portolá expedition, which set out from Loreto on March 9, 1769. Spending holy week at mission Loreto, Serra set out on March 28. "From my mission of Loreto," wrote Serra, "I took along no more provisions for so long a journey than a loaf of bread and a piece of cheese. For I was there [at mission Loreto] a whole year, in economic matters, as a mere guest to receive the crumbs of the royal soldier commissioner, whose liberality at my departure did not extend beyond the aforementioned articles."[44]

Two servants—one named José María Vergerano, a 20-year-old from Magdalena, the other a soldier guard—accompanied Serra on his journey from Loreto, as he rode on a feeble mule. On April 28, 1769, Serra arrived at mission San Borja, where he received a warm welcome from friar Fermín Lasuén. Founded just seven years before by the Jesuit Wenceslaus Linck, mission San Borja sat in an unusually arid region of Baja California. Continuing north, Serra stopped on May 5 to recite a Mass celebrating the feast of the Ascension in the deserted church at Calamajué, scarcely more than a ruined hut. The next morning he arrived at Santa María, where he met up with Portolá, friar Miguel de la Campa and several members of their party. In this arid region, whose alkaline land resisted cultivation, lived the "poorest of all" the Indians Serra had encountered in Mexico. On Sunday May 7, Serra sang high Mass and preached a sermon at the mission church on the frontier of Spanish Catholicism.[45]

Founding Mission Velicatá

After leaving Mission Santa María, Serra urged Portolá to move ahead of the slow pack train, so they could reach Velicatá in time for Pentecost the next day. Portolá agreed, so the small group traveled all day May 13 to reach Velicatá by late evening. The advanced guard of the party greeted them there.

On Pentecost day, May 14, 1769, Serra founded his first mission, Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá, in a mud hut that had served as a makeshift church when friar Fermín Lasuén had traveled up on Easter to recite the sacraments for the Fernando Rivera expedition, the overland party that had preceded the Portolá party. The founding celebration took place "with all the neatness of holy poverty," in Serra's words. Smoke from the soldiers' guns, fired in repeated volleys, served as incense.[46]

The new mission lacked Indians to convert. A few days later, friar Miguel de la Campa notified Serra that a few natives had arrived. Serra joyously rushed out to welcome twelve Indian, men and boys. "Then I saw what I could hardly begin to believe when I read about it," wrote Serra. "…namely, that they go about entirely naked like Adam in paradise before the fall… We treated with them for a long time; and although they saw all of us clothed, they nevertheless showed not the least trace of shame in their manner of nudity." Serra placed both hands upon their heads as a token of paternal affection. He then handed them figs, which they ate immediately. One of the Indian men gave Serra roasted agave stalks and four fishes. In return, Portolá and his soldiers offered tobacco leaves and various food items.[47]

Through a Christian Indian interpreter, Serra told the Indians that de la Campa would stay at the mission to serve them. They should encourage their families and friends to come to the mission. Serra asked them not to harass or kill the cattle. Portolá announced that their chief now had legal status in the name of the king of Spain.

Earthy remedy for leg wound

Back on the road, Serra found it very difficult to stay on his feet because "my left foot had become very inflamed, a painful condition which I have suffered for a year or more. Now this inflammation has reached halfway up my leg…" Portolá again tried to persuade Serra to withdraw from the expedition, offering to "have you carried back to the first mission where you can recuperate, and we will continue our journey." Serra countered that "God…has given me the strength to come so far… Even though I should die on the way, I shall not turn back. They can bury me wherever they wish and I shall gladly be left among the pagans, if it be God's will." Portolá had a stretcher prepared, so that Christian Indians traveling with the expedition could carry Serra along the trail.[48]

Not wishing to burden his traveling companies, Serra departed from his usual practice of avoiding medicines: He asked one of the muleteers, Juan Antonio Coronel, if he could prepare a remedy for Serra's foot and leg wound. When Coronel objected that he knew only how to heal animals' wounds, Serra rejoined: "Well then, son, just imagine that I am an animal… Make me the same remedy that you would apply to an animal." Coronel then crushed some tallow between stones and mixed it with green desert herbs. After heating the mix, he applied it to Serra's foot and leg. The next morning, Serra felt "much improved and I celebrated Mass… I was enabled to make the daily trek just as if I did not have any ailment…There is no swelling but only the itching which I feel at times…"[49]

Trading cloth for fish

The expedition still had 300 miles (480 kilometers) to travel to San Diego. They passed through desert terrain into oak savanna in June, often camping and sleeping under large oaks. From a high hill on June 20, their advance scouts saw the Pacific Ocean in the distance. Reaching its shores that evening, the party called the spot Ensenada de Todos Santos (All Saints' Cove, today simply Ensenada). They now had less than 80 miles (130 kilometers) to reach San Diego.

Pressing north, they stayed close to the ocean. On June 23, they came upon a large Indian village where they enjoyed a pleasant stopover. The natives appeared healthy, robust and friendly, immediately repeating the Spanish words they heard. Some danced for the party, offering them fish and mussels. "We were all enamored of them," wrote Serra. "In fact, all the pagans have pleased me, but these in particular have stolen my heart."[50] The next morning, soldiers traded with the Indians, swapping handkerchiefs and larger pieces of cloth for fish amidst lively bargaining.

The Indians now encountered by the party near the coast appeared well-fed and more eager to receive cloth than food. On June 25, as the party struggled to cross a series of ravines, they noticed many Indians following them. When they camped for the night, the Indians pressed close. Whenever Serra placed his hands of their heads, they placed theirs on his. Coveting cloth, some begged Serra for the friar's habit he wore. Several women passed Serra's spectacles around with delight from hand to hand, until one man dashed off with them. Serra's companions rushed to recover them, the only pair of spectacles Serra possessed.[51]

Arrival in San Diego

On June 28, sergeant José Ortega, who had ridden ahead to meet the Rivera party in San Diego, returned with fresh animals and letters to Serra from friars Juan Crespí and Fernando Parrón. Serra learned that two Spanish galleons dispatched from Baja to supply the new missions had arrived at San Diego Bay. One of the ships, the San Carlos, had sailed almost four months from La Paz, bypassing its destination by almost 200 miles before doubling back south to reach San Diego Bay.[52] By the time it dropped anchor on April 29, scurvy had so devastated its crew that they lacked the strength to lower a boat. Men on shore from the San Antonio, which had arrived three weeks earlier, had to board the San Carlos to help its surviving crew ashore.[53]

The Portolá/Serra party, having trekked 900 miles (1450 kilometers) from Loreto and suffered dwindling food supplies along the way, arrived in San Diego on July 1, 1769. "It was a day of great rejoicing and merriment for all," wrote Serra, "because although each one in his respective journey had undergone the same hardships, their meeting…now became the material for mutual accounts of their experiences…"[54]

Between the overland and seafaring parties of the expedition, about 300 men had started on the trip from Baja California. But no more than half of them reached San Diego. Most of the Christian Indians recruited to the overland parties had died or deserted; military officers had denied them rations when food started running low. Half of those who made it to San Diego spent months unable to resume the expedition, due to illness.[55] Doctor Pedro Prat, who had also sailed on the San Carlos as the expedition's surgeon, struggled to treat the ill men, himself weakened from scurvy. Friar Fernando Parrón, who had sailed on the San Carlos as chaplain, had become weak with scurvy as well. Many men who had sailed on the San Antonio, including captain Juan Pérez, had also taken ill with scurvy.[56] Despite the efforts of Doctor Prat, many of the ill men died in San Diego.

Mission San Diego de Alcalá

On July 16, 1769, Serra founded mission San Diego in honor of saint Didacus of Alcalá in a simple shelter on Presidio Hill serving as a temporary church. Tensions with the local Kumeyaay people made it difficult to attract converts. The Indians accepted the trinkets Serra offered as rewards for visiting the new mission. But their craving for Spanish cloth irritated the soldiers, who accused them of stealing. Some of the Kumeyaay teased and taunted the sick soldiers. To warn them away, soldiers fired their guns into the air. The Christian Indians from Baja who remained with the Spaniards did not know the Kumeyaay language.[57]

Indians attack fledgling mission

On August 15, the Feast of the Assumption, Serra and padre Juan Vizcaíno recited Mass at the new mission chapel, to which several Hispanics had gone for confession and Holy Communion. After Mass, four soldiers went down to the beach to bring padre Fernando Parrón back from the San Carlos, where he had been delivering Mass.

Observing the mission and its neighboring huts sparsely protected, a group of over 20 Indians attacked with bows and arrows. The four remaining soldiers, aided by the blacksmith and carpenter, returned fire with muskets and pistols. Serra, clutching a Jesus figurine in one hand and a Mary figurine in the other, prayed to God to save both sides from casualties. The blacksmith, Chacón, ran about the Spanish huts unprotected by a leather jacket, shouting: "Long live the faith of Jesus Christ and may these dogs, enemies of that faith, die!"[58]

Serra's young servant José María Vergerano ran into Serra's hut, his neck pierced by an arrow. "Father, absolve me," he beseeched, "for the Indians have killed me." "He entered my little hut with so much blood streaming from his temples and mouth that, shortly after, I gave him absolution and helped him to die well," wrote Serra. "…He passed away at my feet, bathed in his blood."[59] Padre Vizcaíno, the blacksmith Chacón, and a Christian Indian from San Ignacio suffered wounds. That night Serra buried Vergerano secretly, concealing his death from the Indians.

The Indian warriors, suffering several dead and wounded, retreated with a new-found respect for the power of Spanish firearms. As local Indians cremated their dead, the wailing of their women sounded from local villages. Yet Serra wrote six months later, in a letter to the guardian of the college of San Fernando, that "both our men and theirs sustained wounds"—without mentioning any Indian deaths. He added: "It seems none of them died so they can still be baptized."[60] Tightening security, the soldiers built a stockade of poles around the mission buildings, banning Indians from entering.

Baptism aborted

A teenage boy from the Kumeyaay village of Kosa'aay (Cosoy, known today as Old Town, San Diego) who had often visited the mission before the outbreak of hostilities, resumed his visits with the friars. He soon learned enough Spanish for Serra to view him as an envoy to help convert the Kumeyaay. Serra urged the boy to persuade some parents to bring their young child to the mission, so that Serra could administer Catholic baptism to the child by pouring water over his head.

A few days later, a group of Indians arrived at the mission carrying a naked baby boy. The Spaniards interpreted their sign language as a desire to have the boy baptized. Serra covered the child with some clothing and asked the corporal of the guard to sponsor the baptism. Dressed in surplice and stole, Serra read the initial prayers and performed the ceremonies to prepare for baptism. But just as he lifted the baptismal shell, filled it with water and readied to pour it over the baby's head, some Indians grabbed the child from the corporal's arms and ran away to their village in fear. The other Kumeyaay visitors followed them, laughing and jeering. The frustrated Serra never forgot this incident; recounting it years later brought tears to his eyes. Serra attributed the Indians' behavior to his own sins.[61]

Just-in-time delivery

Over six months dragged on without a single Indian convert to mission San Diego. On January 24, 1770, the 74 exhausted men of the Portolá expedition returned from their exploratory journey up the coast to San Francisco. They had survived by slaughtering and eating their mules along the return trek south. Commander Gaspar de Portolá, engineer and cartographer Miguel Costansó, and friar Juan Crespí all arrived in San Diego with detailed diaries of their trip. They reported large populations of Indians living along the coast who seemed friendly and docile, ready to embrace the gospel. Serra fervently wrote to the guardian of the college of San Fernando, requesting more missionaries willing to face hardships in Alta California.[62]

Food remained scarce as the San Diego outpost awaited the return of the supply ship San Antonio. Weighing the risk of his soldiers dying of starvation, Portolá set a deadline of March 19, the feast of saint Joseph, patron of his expedition: If no ship arrived by that day—Portolá told Serra—he would march his men south the next morning. The anguished Serra, along with friar Juan Crespí, insisted on staying in San Diego in the event of the Portolá group's departure. Boarding the San Carlos (still anchored in San Diego Bay), Serra told captain Vicente Vila of Portolá's plan. Vila agreed to stay in the harbor until the relief ship arrived—and to welcome Serra and Crespí aboard if they got stranded by Portolá's departure.

On the morning of March 19, Serra sang Mass and preached a sermon at the forlorn mission on Presidio Hill. No ship appeared in the bay that morning. But around 3 o'clock in the afternoon, the sails of a ship—the San Antonio—came into view on the horizon. It sailed past San Diego Bay, destined for Monterey. When it got to the Santa Barbara Channel, its sailors made landfall to fetch fresh water. There they learned from Indians that the Portolá expedition had returned south. So the San Antonio also turned south, anchoring in San Diego Bay on March 23.[63]

Monterey: the northern outpost

Bolstered by the food unloaded from the San Antonio, Portolá and his men shifted their sights back north to Monterey, specified by José de Gálvez as the northern stake of Spain's empire in California. Friar Juan Crespí prepared to accompany the second Portolá expedition to Monterey. Leaving mission San Diego in the hands of friars Fernando Parrón and Francisco Gómez, Serra rode a launch out to board the San Antonio. He and Crespí would meet in Monterey. Since Serra planned to establish the mission there while having Crespí establish mission San Buenaventura, the two friars would be living over 200 miles apart. "Truly," wrote Serra to Palóu, "this state of solitude shall be…the greatest of my hardships, but God in His infinite mercy will see me through."[64]

On April 16, 1770, the San Antonio set sail from San Diego Bay, carrying Serra, doctor Pedro Prat, engineer Miguel Costansó and a crew of sailors under captain Juan Pérez. Contrary winds blew the ship back south to the Baja peninsula, then as far north as the Farallon Islands. As the ship heaved against heavy winds, Pérez, Serra and sailors recited daily prayers, promising to make a novena and celebrate High Mass upon their safe arrival in Monterey.[65] Several sailors fell sick with scurvy. Serra described the six-week voyage as "somewhat uncomfortable."[66]

Meanwhile, the land expedition departed from San Diego on April 17 under the command of Portolá. His group included friar Crespí, captain Pedro Fages, twelve Catalan volunteers, seven leather-jacketed soldiers, two muleteers, five Baja Christian Indians, and Portolá's servant. Following the same route they had taken the year before, the expedition reached Monterey Bay on May 24, without losing a single man or suffering any serious illness.[67] With the San Antonio nowhere in sight, Portolá, Crespí and a guard walked over the hills to Point Pinos, then to a beachside hill just south where their party had planted a large cross five months before on their journey back from San Francisco Bay. They found the cross surrounded by feathers and broken arrows driven into the ground, with fresh sardines and meat laid out before the cross. No Indians were in sight. The three men then walked along the rocky coast south to Carmel Bay. Several Indians approached them, and the two groups exchanged gifts.[68] On May 31, the San Antonio sailed into Monterey Bay and dropped anchor, reuniting the surviving men of the land and sea expeditions.

On Pentecost Sunday, June 3, 1770, Serra, Portolá and the whole expedition held a ceremony at a makeshift chapel erected next to a massive oak tree by Monterey Bay, to found mission San Carlos Borromeo. "The men of the land and sea expeditions coming from different directions met here at the same time," wrote Serra, "we singing the divine praises in our launch, while the gentlemen on land sang in their hearts." After the raising and planting of a large cross, which Serra blessed, "the standards of our Catholic monarch were also set up, the one ceremony…accompanied by shouts of 'Long live the Faith!' and the other by 'Long live the King!' Added to this was the clangor of the bells, the volleys of the muskets, and the cannonading from the ship."[69] Both king Carlos III and viceroy Carlos de Croix had chosen to name the new mission after saint Carlo Borromeo.[70] The body of a sailor, Alexo Niño, who had died the day before aboard the San Antonio, was buried at the foot of the newly erected cross.[71]

Serra realized from the start that the new mission needed relocation: While the Laws of the Indies required missions to be located near Indian villages, there were no Indian settlements near the newly christened mission by Monterey Bay. "It might be necessary," wrote Serra to the guardian of the college of San Fernando, "to change the site of the mission toward the area of Carmel, a locality indeed more delightful and suitable because of the extent and excellent quality of the land and water supply necessary to produce very abundant harvests."[72]

On July 9, the San Antonio set sail from Monterey, bound for Mexico. Aboard were Portolá and Miguel Costansó, along with several letters from Serra. Forty men, including the two friars and five Baja Indians, remained to develop the mission on the Monterey peninsula. In San Diego, 450 miles (725 kilometers) south, 23 men remained to develop the mission there. Both groups would have to wait a year before receiving supplies and news from Mexico.[73]

Missions founded

When the party reached San Diego on July 1, Serra stayed behind to start the Mission San Diego de Alcalá, the first of the 21 California missions[12] (including the nearby Visita de la Presentación, also founded under Serra's leadership).

Junipero Serra moved to the area that is now Monterey in 1770, and founded Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo. He remained there as "Father Presidente" of the Alta California missions. In 1771, Serra relocated the mission to Carmel, which became known as "Mission Carmel" and served as his headquarters. Under his presidency were founded:

- Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcalá, July 16, 1769, present-day San Diego, California.

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, June 3, 1770, present-day Carmel-by-the-Sea, California.

- Mission San Antonio de Padua, July 14, 1771

- Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, September 8, 1771, present-day San Gabriel, California.

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, September 1, 1772, present-day city of San Luis Obispo, California.

- Mission San Juan Capistrano, November 1, 1776, present-day San Juan Capistrano

- Mission San Francisco de Asís, June 29, 1776, present-day San Francisco, California chain of missions.

- Mission Santa Clara de Asís, January 12, 1777, present-day city of Santa Clara, California, and

- Mission San Buenaventura, March 31, 1782, present-day Ventura, California.

Serra was also present at the founding of the Presidio of Santa Barbara (Santa Barbara, California) on April 21, 1782, but was prevented from locating the mission there because of the animosity of Governor Felipe de Neve.

He began in San Diego on July 16, 1769, and established his headquarters near the Presidio of Monterey, but soon moved a few miles south to establish Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo in today's Carmel, California.[8]

The missions were primarily designed to bring the Catholic faith to the native peoples. Other aims were to integrate the neophytes into Spanish society, to provide a framework for organizing the natives into a productive workforce in support of new extensions of Spanish power, and to train them to take over ownership and management of the land. As head of the order in California, Serra not only dealt with church officials, but also with Spanish officials in Mexico City and with the local military officers who commanded the nearby garrison.

In 1773, difficulties with Pedro Fages, the military commander, compelled Serra to travel to Mexico City to argue before Viceroy Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa for the removal of Fages as the Governor of California Nueva. At the capital of Mexico, by order of Viceroy Bucareli, he printed up Representación in 32 articles. Bucareli ruled in Serra's favor on 30 of the 32 charges brought against Fages, and removed him from office in 1774, after which time Serra returned to California. In 1778, Serra, although not a bishop, was given dispensation to administer the sacrament of confirmation for the faithful in California. After he had exercised his privilege for a year, Governor Felipe de Neve directed him to suspend administering the sacrament until he could present the papal brief. For nearly two years Serra refrained, and then Viceroy Majorga gave instructions to the effect that Serra was within his rights.

Franciscans saw the Indians as children of God who deserved the opportunity for salvation, and would make good Christians. Converted Indians were segregated from Indians who had not yet embraced Christianity, lest there be a relapse. To understand the impetus behind missionary efforts in the 18th century, one must take into account the era's views on the salvation of unbaptized infants. While there were many controversies in the Church's history, the fate of unbaptized infants was never a serious point of contention, for which reason the Church to this day has not deemed it necessary to settle the issue definitively.

Catholics are therefore free to speculate and hold a variety of opinions on the matter. In the 18th century, most Catholic speculation regarding the ultimate end of unbaptized infants was still in line with the early Church Fathers such as St. Augustine of Hippo, who believed that unbaptized infants would receive the mildest chastisements in Hell, but no reward. While several theologians from the 12th Century onward (notably Peter Abelard) had suggested that unbaptized infants would spend eternity in natural happiness in Limbo, and several mystics such as Mary of Agreda and Marcel Van had affirmed that unbaptized children ultimately go to Heaven, it is only very recently that the private speculation of Catholic theologians has leaned toward this position.

For Serra and his companions, therefore, instructing the natives so that their children might also be saved would have most likely been a great concern. From this came the determined efforts of missionaries to the detriment of native cultures, which few today would countenance.[74]

Discipline was strict, and the converts were not allowed to come and go at will. Indians who were baptized were required to live at the mission and conscripted into forced labor as plowmen, shepherds, cattle herders, blacksmiths, and carpenters on the mission. Disease, starvation, over work, and torture decimated these tribes.[75]:114 Serra successfully resisted the efforts of Governor Felipe de Neve to bring Enlightenment policies to missionary work, because those policies would have subverted the economic and religious goals of the Franciscans.[76]

Serra wielded this kind of influence because his missions served economic and political purposes as well as religious ends. The number of civilian colonists in Alta California never exceeded 3,200, and the missions with their Indian populations were critical to keeping the region within Spain's political orbit. Economically, the missions produced all of the colony's cattle and grain, and by the 1780s were even producing surpluses sufficient to trade with Mexico for luxury goods.[77]

In 1779, Franciscan missionaries under Serra's direction planted California's first sustained vineyard at Mission San Diego de Alcalá. Hence, he has been called the "Father of California Wine". The variety he planted, presumably descended from Spain, became known as the Mission grape and dominated California wine production until about 1880.[78]

During the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), Serra took up a collection from his mission parishes throughout California. The total money collected amounted to roughly $137, but the money was sent to General George Washington. Serra also received the title Founder of Spanish California.

Treatment of Native Californians

Serra had a singular purpose in mind, to save Native American souls. He believed that the death of an unconverted heathen was tragic, while the death of a baptized convert was a cause for joy.[79]:39 He maintained a patriarchal or fatherly attitude towards the Native American population. He wrote, "That spiritual fathers should punish their sons, the Indians, with blows appears to be as old as the conquest of the Americas; so general in fact that the saints do not seem to be any exception to the rule."[77] Punishment made clear to the natives "that we, every one of us, came here for the single purpose of doing them good and their eternal salvation."[79]:39

Cultural oppression

The New York Times noted that some "Indian historians and authors blame Father Serra for the suppression of their culture and the premature deaths at the missions of thousands of their ancestors."[4] George Tinker, an Osage/Cherokee and professor at Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado,[80] cites evidence that Serra required the converted Indians to labor to support the missions. Tinker writes that while Serra's intentions in evangelizing were honest and genuine,[81] overwhelming evidence suggests that the "native peoples resisted the Spanish intrusion from the beginning".[82]

While administering Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Monterey, California, Serra had ongoing conflicts with Pedro Fages, who was military governor of Alta California. Fages worked his men very harshly and was seen as a tyrant. Serra intervened on the soldier's behalf, and the two did not get along.[83][84] The soldiers raped the Indian woman and kept them as concubines.[83] Serra moved the mission to Carmel due to better lands for farming, due to his conflicts with Fages, and in part to protect the Indian neophytes from the Spanish soldiers.[85]

Mark A. Noll, a professor at Wheaton College in Illinois, wrote that Serra's attitude—that missionaries could, and should, treat their wards like children, including the use of corporal punishment—was common at the time.[86]

Tinker argues that it is more appropriate to judge the beatings and whippings administered by Serra and others from the point of view of the Native Americans, who were the victims of the violence, and who did not punish their children with physical discipline.[87]

Salvatore J. Cordileone, the current archbishop of San Francisco, acknowledges Native American concerns about Serra's whippings and coercive treatment, but argues that missionaries were also teaching school and farming.[4]

Iris Engstrand, a professor of history at the Roman Catholic University of San Diego, described Serra as:

much nicer to the Indians, really, than even to the governors. He didn't get along too well with some of the military people, you know. His attitude was, 'Stay away from the Indians'. I think you really come up with a benevolent, hard-working person who was strict in a lot of his doctrinal leanings and things like that, but not a person who was enslaving Indians, or beating them, ever....He was a very caring person and forgiving. Even after the burning of the mission in San Diego, he did not want those Indians punished. He wanted to be sure that they were treated fairly . . . "[8]

Deborah A. Miranda, a professor of American literature at Washington and Lee University and Native American, stated that "Serra did not just bring us Christianity. He imposed it, giving us no choice in the matter. He did incalculable damage to a whole culture".[4]

Professor Edward Castillo, a Native American and director of Native American Studies at the Sonoma State University in California, said in a Firing Line episode with William F. Buckley, Jr. that, "...you pointed out [that] in my work I haven't cited Serra as oppressor. You can't put a whip in his hand. You can't put a smoking gun in his hand. And that is true. The man was an administrator."[88]

Corine Fairbanks of the American Indian Movement proclaimed that “For too long the mission system has been glorified as these wonderful moments of California’s golden era. That is not true. They were concentration camps. They were places of death.”[89]

Support for canonization

Despite these concerns, thousands of Native Americans in California maintain their Catholic faith,[90] and some supported efforts to canonize Serra.[91][92] James Nieblas, 68 – the first Native American priest to be ordained from the Juañeno Acjachemen Nation, a tribe evangelized by Serra, was chosen to meet with Pope Francis during his visit to Washington D.C.[93] Nieblas, a longtime supporter of Serra's canonization, stated during a 1986 interview with the Los Angeles Times that "Father Serra brought our people to this day. I think Serra would be proud...canonization has the full support and backing of the Juaneno people."[94]

Members of other tribes associated with mission system also expressed support for Serra's canonization. “Our people were directly involved with the Carmel Mission,” said Tony Cerda, tribal chief of the Costanoan Rumsen Carmel tribe. “We support the canonization...The mission lands were our ancestral homes. Our ancestors are buried at the mission."[95]

On the Costanoan Rumsen Carmel Tribe's official website, the community released a bilingual statement in support of Serra's canonization shortly after a visit between Chief Cerda and Pope Francis, stating:

Saint Junipero Serra Baptized and Married our ancestors Simon Francisco (Indian name "Chanjay") and Magdalena Francisca on April 1, 1775 at Mission San Carlos De Borromeo Del Rio Carmelo...We wholeheartedly Support the canonization of Saint Junipero Serra because he protected our people and supported their full human rights against the politicians and the military with total disregard for his own life and safety.[96]

Two members of California’s Ohlone Tribe played roles in the canonization Mass by placing a relic of Serra’s near the altar and reading a scripture in Chochenyo, a native language. One of the participants, Andrew Galvan, a member of the Ohlone Tribe and curator of Mission Dolores in San Francisco, stated prior to the ceremony that the canonization “will be the culmination of a life’s work for me…It will be a ceremonial opening of the door that will ‘let us Indians in,’ a moment I honestly didn’t think I would live to see.”[91]

Ruben Mendoza, an archeologist of Mexican Mestizo and Native Yaqui descent who has extensively excavated missions in California, stated during a March 2015 interview with the Los Angeles Times that "Serra endured great hardships to evangelize Native Californians. In the process, he orchestrated the development of a chain of missions that helped give birth to modern California….When I don't go along with the idea that the missions were concentration camps and that the Spanish brutalized every Indian they encountered, I'm seen as an adversary."[92]

In July 2015, Mendoza testified at a hearing on a proposal to remove a statue of Junipero Serra from the U.S. Capitol. In his remarks, he stated, “What greater symbol of empowerment than that offered by Fray Junípero Serra himself can we offer our youth? I ask that this legislative body seriously reconsider this politicized effort to minimize and erase one of the most substantive Hispanic and Latino contributions to our nation’s history.”[97]

_-_basilica%2C_interior%2C_grave_of_Junipero_Serra.jpg)

Biographer Gregory Orfalea wrote of Serra: "I see his devotion to Native Californians as heartfelt, plain-spoken and borne out by continuous example." [98][99]

Death and burial

During the remaining three years of his life, he once more visited the missions from San Diego to San Francisco, traveling more than 600 miles in the process, to confirm all who had been baptized. He suffered intensely from his crippled leg and from his chest, yet he would use no remedies. He confirmed 5,309 people, who, with but few exceptions, were California Indian neophytes converted during the fourteen years from 1770.

On August 28, 1784, at the age of 70, Junípero Serra died at Mission San Carlos Borromeo. He is buried there under the sanctuary floor.[8] Following Serra's death, leadership of the Franciscan missionary effort in Alta California passed to Fermín Lasuén.

Veneration

Junípero Serra was beatified by Pope John Paul II on September 25, 1988.[100] The pope spoke before a crowd of 20,000 in a beatification ceremony for six; according to the pope's address in English, "He sowed the seeds of Christian faith amid the momentous changes wrought by the arrival of European settlers in the New World. It was a field of missionary endeavor that required patience, perseverance, and humility, as well as vision and courage."[101]

During Serra's beatification, questions were raised about how Indians were treated while Serra was in charge. The question of Franciscan treatment of Indians first arose in 1783. The famous historian of missions Herbert Eugene Bolton gave evidence favorable to the case in 1948, and the testimony of five other historians was solicited in 1986.[102][103][104]

Serra was canonized by Pope Francis on September 23, 2015, as a part of the pope's first visit to the United States, the first canonization to take place on American soil.[105] Nevertheless, Serra's life underwent the same level of scrutiny the Vatican requires of all canonizations, including the compilation of thousands of pages of materials about his life and work.[106] He is the first native saint of the Balearic Islands. During a speech at the Pontifical North American College in Rome on May 2, 2015, Pope Francis stated that "Friar Junípero ... was one of the founding fathers of the United States, a saintly example of the Church’s universality and special patron of the Hispanic people of the country."[1]

Serra's feast day is celebrated on July 1 and he is considered to be the patron saint of California, Hispanic Americans, and religious vocations.

The Mission in Carmel, California containing Serra's remains has continued as a place of public veneration. The burial location of Serra is southeast of the altar and is marked with an inscription in the floor of the sanctuary. Other relics are remnants of the wood from Serra's coffin on display next to the sanctuary, and personal items belonging to Serra on display in the mission museums. A bronze and marble sarcophagus depicting Serra's life was completed in 1924 by Catalan sculptor Joseph A. Mora, but Serra's remains have never been transferred to that sarcophagus.

Legacy

Many of Serra's letters and other documentation are extant, the principal ones being his "Diario" of the journey from Loreto to San Diego, which was published in Out West (March to June 1902) along with Serra's "Representación."'

The Junípero Serra Collection (1713–1947) at the Santa Barbara Mission Archive-Library are their earliest archival materials. The Santa Barbara Mission-Archive Library is part of the building complex of the Mission Santa Barbara, but is now a separate non-profit, independent educational and research institution. The Santa Barbara Mission-Archive Library continues to have ties to the Franciscans and the legacy of Serra.[107]

The chapel at Mission San Juan Capistrano, built in 1782, is thought to be the oldest standing building in California. Commonly referred to as "Father Serra's Church,"[108] it is the only remaining church in which Serra is known to have celebrated the rites of the Roman Catholic Church (he presided over the confirmations of 213 people on October 12 and October 13, 1783).

Many cities in California have streets, schools, and other features named after Serra. Examples include Junipero Serra Boulevard, a major boulevard in and south of San Francisco; Serramonte, a large 1960s residential neighborhood on the border of Daly City and Colma in the suburbs south of San Francisco; Serra Springs, a pair of springs in Los Angeles; Serra Mesa, a community in San Diego; Junipero Serra Peak, the highest mountain in the Santa Lucia Mountains; Junipero Serra Landfill, a solid waste disposal site in Colma; and Serra Fault, a fault in San Mateo County. Schools named after Serra include Junípero Serra High School, a public school in the San Diego community of Tierrasanta, and four Catholic high schools: Junípero Serra High School in Gardena, Junipero Serra High School in San Mateo, JSerra Catholic High School in San Juan Capistrano, and Serra Catholic High School in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. There are public elementary schools in San Francisco and Ventura, as well as a K-8 Catholic school in Rancho Santa Margarita.

Both Spain and the United States have honored Serra with postage stamps.

In 1884, the Legislature of California passed a concurrent resolution making August 29 of that year, the centennial of Serra's burial, a legal holiday.[109]

Serra International, a global lay organization that promotes religious vocations to the Catholic Church, was named in his honor. The group, founded in 1935, currently numbers a membership of about 20,000 worldwide. It also boasts over 1,000 chapters in 44 countries.[110]

Serra's legacy towards Native Americans has been a topic of discussion in the Los Angeles area in recent years. The Mexica Movement, a radical indigenous separatist group that rejects European influence in the Americas,[111] protested Serra's canonization at the Los Angeles Cathedral in February 2015.[112] The Huntington Library announcement of its 2013 exhibition on Serra made it clear that Serra's treatment of Native Americans would be part of the comprehensive coverage of his legacy.[113]

On September 27, 2015, in response to Serra's canonization, the San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo Mission was vandalized. The statue of Serra was toppled and splattered with paint, and the cemetery, the mission doors, a fountain, and a crucifix were as well. The message "Saint of Genocide" was put on Serra's tomb, and similar messages were painted elsewhere in the mission courtyard.[114][115] After the incident, law enforcement authorities launched a hate crime investigation since the only grave sites targeted for desecration were those of Europeans.[116]

Statuary and monuments

- A statue of Friar Junípero Serra is one of two statues that represent the state of California in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol. The work of Ettore Cadorin, it depicts Serra holding a cross and looking skyward. In February 2015, State Senator Ricardo Lara introduced a bill in the California legislature to remove the statue and replace it with one of astronaut Sally Ride. In May 2015, some California Catholics were organizing to keep Serra's statue in place. California Governor Jerry Brown supported retaining it when he visited the Vatican in July, 2015 .[117][118] On July 2, Lara announced that as a gesture of respect towards Pope Francis and people of faith, the vote on the bill would be postponed until the following year. Pope Francis canonized Serra as part of his September 2015 papal visit to the US.[119]

- A gold statue of heroic scale represents him as the apostolic preacher at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.

- In 1899 Jane Elizabeth Lathrop Stanford, wife of Leland Stanford, governor and U.S. Senator from California, and a non-Catholic herself, commissioned a granite monument to Serra which was erected in Monterey in 1891. The figure of Serra was decapitated in October 2015,[120] and the head not found until April 2, 2016, in Monterey Bay.[121]

- When Interstate 280 was built in stages from Daly City to San Jose in the 1960s, it was named the Junipero Serra Freeway. A statue of Serra on a hill on the northbound side of the freeway in Hillsborough, California points a finger towards the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Pacific.

- A bronze statue of Serra standing over an outline of the State of California stands in the California State Capitol's Capitol Park. It faces a statue of Thomas Starr King, previously located in the National Statuary Hall Collection.

- A bronze statue of Serra stands in Ventura in front of city hall at the corners of California and Poli Streets

- A statue of Serra is located in the courtyard of Mission Dolores, San Francisco's oldest remaining building.

- A life-size bronze statue of Serra overlooks the entrance to Mission Plaza in San Luis Obispo, near the façade of Old Mission San Luis Obispo.

- Statues or other monuments to Father Serra are found on the grounds of several other mission churches, including those in San Diego and Santa Clara.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Pope Francis celebrates Junipero Serra at Rome's North American College". Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Patron Saints and their feast days". Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "Pope to Canonize ‘Evangelizer of the West’ During U.S. Trip". National Catholic Register. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Pogash, Carol (January 21, 2015). "To Some in California, Founder of Church Missions Is Far From Saint". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Serra's baptismal record" (JPG). Agència Baleria (in Catalan). Palma, Majorca. 24 November 1713. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ↑ Hackel, Steven W. (2013-09-03). Junipero Serra: California's Founding Father. Macmillan. pp. 16. ISBN 9780809095315.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra, O.F.M.: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 "Blessed Junípero Serra 1713 – 1784". Serra Club of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 15.

- ↑ Geiger, Maynard, "The Life and Times of Padre Serra", Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1959, p. 26

- ↑ Maynard Geiger, The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra, O.F.M.: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 2, p. 375.

- 1 2 "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Junipero Serra". newadvent.org. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 28–9.

- ↑ Junípero Serra, letter to Francesch Serra, Cádiz, August 20, 1749. Writings of Junípero Serra. Antonine Tibesar, O.F.M., editor. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1955, vol. 1, p. 5.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 4.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra,: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 86–7. Geiger discussed Serra's wound with three medical doctors—one of them Mexican—to fact-check this account from Serra and his first biographer, Francisco Palóu. Serra's wound may have been caused either by a mosquito bite or infestation by a "chigger," more precisely a chigoe flea.

- ↑ Eric O'Brien, O.F.M. "The Life of Padre Serra." Writings of Junípero Serra. Antonine Tibesar, editor. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1955, vol. 1, p. xxxii.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 49-50.

- ↑ Rose Marie Beebe, Robert M. Senkewicz, Junípero Serra: California, Indians, and the Transformation of a Missionary, University of Oklahoma Press, 2015, Google Books

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 501.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra, O.F.M.: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 116–17.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 52.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 55-6.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 55.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra, O.F.M.: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 115.

- ↑ "Report to the Inquisition of Mexico City." Xalpan, September 1, 1752. Writings of Junípero Serra. Antonine Tibesar, O.F.M., editor. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1955, vol. 1, pp. 19–21 (HathiTrust).

- ↑ Writings of Junípero Serra. Antonine Tibesar, O.F.M., editor. Acadummy of American Franciscan History, 1955, vol. 1, p. 410 (reference note).

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 149

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 56.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra,: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 146–7.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra,: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 171–2 (drawing on Francisco Palóu's account).

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 59.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra,: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 172–3.

- ↑ James J. Rawls and Walton Bean. California: An Interpretive History, 8th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2003, p. 34.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 6-7.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 182–3.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 183–4.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 192.

- ↑ DeNevi, Moholy & Harper & Row 1985, p. 64-8.

- ↑ DeNevi, Moholy & Harper & Row 1985, p. 66.

- ↑ Francisco Palóu, 24 November 1769 report to the guardian of the college of San Fernando. MM 1847, f 273, Bancroft Library, Berkeley, California.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, pp. 69–72.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 75.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 211.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 78.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 79.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 80.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 219–20.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 220–1.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 84.

- ↑ DeNevi & Moholy 1985, p. 85-6.

- ↑ "Pedro Fages and Miguel Costansó: Two Early Letters From San Diego in 1769". Journal of San Diego History, vol. 21, no. 2, spring 1975. Translated and edited by Iris Wilson Engstrand.

- ↑ James J. Rawls and Walton Bean. California: An Interpretive History, 8th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp. 35–6.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 227.

- ↑ James J. Rawls and Walton Bean. California: An Interpretive History, 8th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2003, p. 36.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 231.

- ↑ Don DeNevi and Noel Francis Moholy. Junípero Serra: The Illustrated Story of the Franciscan Founder of California's Missions. Harper & Row, 1985, p. 93-4.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 234.

- ↑ Serra's letter to Juan Andrés at the college of San Fernando, Feb. 10, 1770. Writings of Junípero Serra. Antonine Tibesar, O.F.M., editor. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1955, vol. 1, p. 151.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 235.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 233, 235–6.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 237.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 240–1.

- ↑ Junípero Serra, letter to Francisco Palóu, April 16, 1770. Writings of Junípero Serra. Antonine Tibesar, O.F.M., editor. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1955, vol. 1, p. 163.

- ↑ Don DeNevi and Noel Francis Moholy. Junípero Serra: The Illustrated Story of the Franciscan Founder of California's Missions. Harper & Row, 1985, p. 103.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 246, 247.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 246.

- ↑ Don DeNevi and Noel Francis Moholy. Junípero Serra: The Illustrated Story of the Franciscan Founder of California's Missions. Harper & Row, 1985, p. 99.

- ↑ Serra's letter to Juan Andrés, June. 12, 1770. Writings of Junípero Serra. Antonine Tibesar, O.F.M., editor. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1955, vol. 1, pp. 169–71.

- ↑ Don DeNevi and Noel Francis Moholy. Junípero Serra: The Illustrated Story of the Franciscan Founder of California's Missions. Harper & Row, 1985, p. 100.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, p. 248.

- ↑ Serra's letter to Juan Andrés, June. 12, 1770. Writings of Junípero Serra. Antonine Tibesar, editor. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1955, vol. 1, p. 171.

- ↑ Maynard Geiger. The Life and Times of Fray Junípero Serra: The Man Who Never Turned Back. Academy of American Franciscan History, 1959, vol. 1, pp. 252–3.

- ↑ "Lumen Gentium" (16)

- ↑ Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- ↑ Francis P. Guest, "Junipero Serra and His Approach to the Indians," Southern California Quarterly, (1985) 67#3 pp 223–261

- 1 2 "Junipero Serra". pbs.org. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ LaMar, Jim., Professional Friends of Wine,"Wine 101: History". Retrieved on April 6, 2007

- 1 2 Nugent, Walter (1999). Into the West: The Story of its People (First ed.). New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0679454793.

- ↑ Tinker, George E. , "Missionary Conquest," Chap. 3, Fortress Press, 1993, pages 42 and 61

- ↑ Tinker, p. 42.

- ↑ Tinker, p. 59.

- 1 2 Walton, John (2003). Storied Land: Community and Memory in Monterey. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. p. 15ff. ISBN 9780520935679. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Paddison, p. 23: Fages regarded the Spanish installations in California as military institutions first, and religious outposts second.

- ↑ Breschini, Ph.D., Gary S. (2000). "Mission San Carlos Borromeo (Carmel)". Monterey County Historical Museum. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ Noll, Mark A., A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada, pp. 15 – 16, Wm. B. Erdmans Publishing, 1992

- ↑ Tinker, p. 58.

- ↑ Southern Educational Communications Association (SECA) (17 March 1989). "Firing Line with William F. Buckley: Saint or Sinner: Junipero Serra" – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ http://www.montereyherald.com/article/NF/20150401/NEWS/150409963

- ↑ Cultural Diversity in the Catholic Church in the United States