Franklin Place

.jpg)

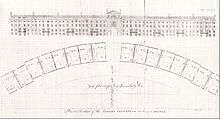

Franklin Place, designed by Charles Bulfinch and built in Boston, Massachusetts in 1793-95, included a row of sixteen three-story brick townhouses that extended in a 480-foot[1] curve, a small garden, and four double houses. Constructed early in Bulfinch’s career, Franklin Place came after he had seen the possibilities of modern architecture in Europe and had determined to reshape his native city.[2] It was the first important urban housing scheme undertaken in the United States,[3] and the city’s first row-house complex.[4] However, years of decline and the push of industry into the area forced its demolition in 1858.

The Tontine Crescent

.jpg)

The name “Tontine” derives from a financial scheme originated by Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti, which he introduced in France in the 17th century. Money for the enterprise was to be raised by selling shares of stock to the members of the public, who would later share in the profits from the sale of the homes. It is essentially an annuity, the shares passing on the death of each beneficiary to the surviving partner until all are held by a single shareholder, or being divided among surviving stockholders at the end of a stated period.[5] Although this method of financing was in rather wide use in Europe at the time, the Massachusetts General Court refused articles of incorporation and the project ultimately rested on Bulfinch’s meager business talent.

On July 6, 1793, the Columbian Centinel carried the following notice:

“The public are hereby informed that a plan is proposed for building a number of convenient, elegant HOUSES, in a central situation, and a scheme of tontine association. The proposals for subscription, and the plans of the Houses, may be seen at the office of Mr. JOHN MARSTON, State-Street.” By the end of the month a sufficient number of subscriptions had been received to warrant the letting of contracts for “the framing, and the door-cases and window-frames of the proposed Tontine Building.”[6]

The cornerstone was laid on August 8, and the crescent was completed the following year.[7]

Building began with less than 50% of the shares taken up and continued in a discouraging atmosphere created by the prolonged negotiations over the Jay Treaty. Bulfinch completed the project, including its complementary file of four double houses facing across the grass plot (17-24 Franklin Place), but in so doing sacrificed both his and his wife’s fortunes. As events proved, the Crescent was far too ambitious an idea for either the man or the times, and he and his family were ruined by his determination to finish it at all costs. However, he was gratified “in knowing that not one of my creditors was materially injured, many were secured the full amount, and the deduction on the balance due to workmen did not exceed 10 PC on their entire bills.”[8]

Bulfinch’s first attempt to introduce monumental town planning into Boston, the Crescent was an interesting failure, unlike any other building in America. In fact, not even London had a crescent at the time; the architect relied for his model primarily on examples he had seen in Bath[9]—a memory reinforced by a folio of Bath pictures preserved in his library. The Crescent no doubt also owed something to the well-known plan Robert Adam devised for two half circles of connecting houses as an extension of London’s Portland Place, as well as certain examples Bulfinch had seen in Paris. In architectural detail, the Crescent recalls the Adelphi Terrace, which Bulfinch knew both as a center of Neoclassical building in London and as the haunt of exiled Tory relatives and family friends. (Adelphi too was a financial disaster, and the Adam brothers saved their project only through a lottery and the sale of their art collections; Bulfinch lacked such resources.)

This innovative project for a new and fashionable residential district south of the central business district was located in an undeveloped, unpromising bit of fields and marshlands between Milk Street and Summer Street that consisted in part of a quagmire that Joseph Barrell—Bulfinch’s former employer, who had a house on Summer Street—had partially drained and converted into a fish pond in his garden.[10] Its western edge intersected today’s Hawley Street, and on the east it ended near Federal Street. Until the American Revolution, Boston still had enough space in most locations to accommodate single dwellings with small gardens. However, as land values began to rise, many newer dwellings began to be built with their narrow ends to the street and their entrances on the side. With his long row of attached houses, Bulfinch gambled that wealthy individuals would not mind living in relatively cramped quarters. Knowing that most wealthy Londoners living in garden squares also had country estates, he believed perhaps that potential residents of Franklin Place would also have summer homes with large gardens elsewhere.[11]

Thomas Pemberton described the Crescent at the time of completion as “a range of sixteen well built and handsome dwelling houses, extending four hundred and eighty feet in length…The general appearance is simple and uniform.”[12] As Bulfinch’s elevation shows, the chief feature was a central pavilion, slightly higher than the Crescent’s wings, with a large arch that spanned a passageway passing entirely through the structure, an attic story and two secondary pavilions projecting 6’ forward from the middle section.[13] The form was suggested by Queen’s Square in Bath, constructed more than half a century earlier by John Wood, the Elder; the arch, with Palladian window, was probably taken from the Market in High Street, Bristol, traditionally attributed to Wood also. However, in style the Tontine Crescent was Neoclassical rather than Neo-Palladian, and its main architectural distinction, three ranges of pilasters rising two stories above an architectural basement,[14] is taken from the Adelphi. Moreover, the structure contained all the Neoclassical elements of the new Federal style: attenuated pilasters on the central pavilion and two end pavilions that projected forward several feet, swag panels, and delicate fanlights and lunettes.[15] The plan, which featured two large rooms (about 18’ x 18’) on each floor offset by a hallway with main and service staircases, was traditional with London row-house builders since the 17th century. Indeed, the Neoclassical façade of the Adam brothers’ Royal Society of Arts building in London was another inspiration for the central building.[16] The houses’ brick[17] exterior walls were painted gray to simulate masonry[18] and the architectural detail, apparently all of wood, was painted white. Delicate decorative devices were present on the handsome three-floor houses, each 27’ wide, but ornament was so restrained that there were no frames around the windows. The identical doorways were spaced two to a porch. Each floor consisted of two large rooms, described by Massachusetts Magazine as “spacious and lofty”, with a hallway on one side containing both the main and service stairways.[15]

Once finished, the Crescent received unanimous praise from contemporaries. Asher Benjamin claimed it “gave the first impulse to good taste; and to architecture, in this part of the country.”[19] Massachusetts Magazine called the style “the most improved of modern elegance” and was especially impressed by the spacious rooms and the attention given to household conveniences: “Each house will have annexed to it a pump, rain water cistern, wood house, and a stable, and a back avenue will communicate to all the stables.”[20] Bulfinch was also praised for presenting the large room behind the Palladian window above the arch to the Boston Library Society[21] and the attic above to the newly founded Massachusetts Historical Society,[22] which at the time was lodged in the northwest corner of Faneuil Hall’s attic. (Granted, Bulfinch and his partners did realize it might be difficult to find buyers for the two pavilion rooms, potentially unsuitable for residences.)[15] The Library Society remained there until the building’s demolition in 1858, when the city paid it $12,000 for its room, while the Historical Society stayed until 1833, moving next to the King's Chapel burying ground because of cramping and fear of fire.[23]

17-24 Franklin Place

The four double houses in Franklin Place substituted for the northern half of what was planned as a double crescent separated by an oval of grass. This solution, although less aesthetically successful, was dictated by difficulties in acquiring sufficient land adjoining the estate of Thomas Barrell for the execution of the original scheme. It is also evident that Bulfinch’s approaching financial ruin precluded the construction of anything so costly as the projected northern crescent. As it was, the architect was hopelessly in debt when he began building on the north side of Franklin Place, probably in December 1794.[24] The earliest reference to the project is in Pemberton’s description of the recently completed Crescent: “The opposite side is intended to be built in a straight line, and in a varied style of building.”[25] On October 15, 1795, the eastern half of one of the buildings, Number 22, was sold to John McLean for $8,000, and it is presumed the range of four brick double houses was completed shortly thereafter.[26] The entire property, including the houses in the Crescent and the four double ones in Franklin Place, was assessed in the Direct Tax of 1798 at something over $125,000. By that time, five years after the beginning of construction on Franklin Place, all twenty-four properties had been sold and were occupied by the families of prominent businessmen and men of letters.[27]

As the site plan made for the Historic American Buildings Survey shows, the axis of the Crescent and the double houses opposite was along the line of Arch Street with the Franklin Urn serving as a focus. The four double houses were of the same architectural proportions, although the middle pair was somewhat larger in area. The end houses were placed obliquely to the middle ones and thus corresponded to the east and west pavilions of the Crescent; the slight angle helped keep the street openings as wide as possible.[15] The houses on both sides of the street had identical fanlight entrance doors, and despite Pemberton’s prediction of variety in architectural treatment, the double houses were quite similar to the opposing Crescent. The major stylistic differences were Bulfinch’s exclusive use of swag panels in the Crescent and recessed brick arches in the houses across the way. No floor plan has been discovered but it is presumed the double houses had the traditional arrangement of two rooms on either side of a transverse hallway divided, as in the Crescent, by main and service staircases. The two center units were much larger than the pairs at the ends and included tiny fenced-in front gardens.[15] The row faced south on the enclosed grass plot and was considered at the time the most modern and pleasant range of houses in Boston.

Other characteristics

Between the Crescent and the double houses was a wrought-iron-fenced semi-oval grass plot 40’ wide at its center and about 280’ long, with shade trees; it was at the heart of the city’s first garden square.[28] In 1795, Bulfinch placed a large Neoclassical urn (similar to one executed by Robert Adam) and pedestal in the square’s center; he had purchased these in Bath and brought them home from his Grand Tour of 1785-87. Soon after 1858, the urn, which served as a memorial to the late Benjamin Franklin, was moved together with the pedestal to Bulfinch’s grave in Mount Auburn Cemetery. While much smaller than its London counterparts, the garden was important for recreation, and its shape echoed that of the surrounding buildings. Also unlike in London, where gated streets allowed entry only to residents, access to the garden was not restricted and it could be enjoyed by visitors to the Library and Historical Societies, as well as by theater- and church-goers.[29] As Massachusetts Magazine observed in 1794, the garden “will contribute to the ornament of the buildings, and be useful in promoting a change and circulation of air.”[30]

Also as part of the complex were included Boston Theater (1793), the first theater built in Boston, placed at the northeast end of the square, and Holy Cross Church (begun 1800), the city’s first Roman Catholic church, directly opposite the theater at the southeast end. These additional amenities for residents recalled what St Albans had done for St. James's Square, and were a bold move, considering that Puritan Boston had banned theatrical performances until December 1793 and had displayed religious intolerance throughout its history.[16]

What the social life in Franklin Place was like is suggested by two paintings, now held by the Museum of Fine Arts: Henry Sargent’s The Dinner Party (ca. 1821) and The Tea Party (ca. 1824). These probably represent actual parties that took place in Sargent’s home at 10 Franklin Place, on the Crescent. Based on Bulfinch’s plan, the two rooms depicted in The Tea Party must have been adjoining parlors, most likely on the second floor above the first-floor dining room. The graceful archway connecting the two rooms in the picture is a Neoclassical architectural detail used by Bulfinch to relate the interior of the house to the Palladian window on the Crescent’s central building. Despite the rooms’ long, narrow configuration, lavish entertainment could still take place, in part because the high ceilings made the rooms seem larger. Bulfinch’s drawing of the Crescent suggests that the first- and second-floor windows were of the same height; this is consistent with the interiors shown in the painting and contrasts with London terraces of the period, where the second-floor parlor windows were usually taller. The furnishings that Sargent depicts represent contemporary high-style Boston interiors, in most respects similar to what could be found in London. The dining room in The Dinner Party is quite masculine, with mahogany furniture and large portraits suitable to the gathering of gentlemen, the two parlors or drawing rooms shown in The Tea Party are lighter in feeling, more feminine, and ornamented with many French and Italian decorative objects. The women are adorned with the latest and most expensive fashions of the day—column-like Empire gowns with accompanying shawls.[31]

Demolition and legacy

.jpg)

Notable residents of Franklin Place included John and Judith Sargent Murray, Abby May,[32] James Perkins, merchant and principal donor to the Boston Athenaeum’s first building, William Tudor, Jr., founder of Monthly Anthology and the North American Review, and his literary associate Dr. John S. J. Gardiner, rector of Trinity Church. Two women owned houses: Abigail Howard, a founder of the Boston Library Society, and Elizabeth Amory.[33] While wealthy merchants and prominent men of letters inhabited both the Crescent and the houses across the street, it was the free-standing houses that became the most fashionable, even though they were more expensive and the side yards were very narrow; Bostonians had a deep-seated preference for even the narrow yards of semi-detached houses as opposed to the block of connected houses, two walls in each of which had to be windowless. The pattern held true in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: except for a few houses in the Back Bay, Bostonians at every class level utterly rejected the connected town house block and instead turned back to some version of the 18th- and early 19th-century ideal of the garden lot and free-standing town house.[34]

Shortly after the Crescent’s completion, the newly widened Arch Street was extended through the center archway, and other connecting streets were opened to the south and east. The addition of these new streets reflected the growth of the downtown business area immediately surrounding the complex; this long-lasting push by businesses into the area would eventually doom Bulfinch’s buildings.[27] After about thirty years, when the Mount Vernon Proprietors were developing an exclusive residential neighborhood on Mount Vernon just to the west of Beacon Hill that was beginning to lure affluent residents farther from the central business district, middle-class residents began to move in. The single-family dwellings were soon converted into boarding houses. The new residents were less concerned with the neighborhood’s overall appearance, as seen from late photographs that show the garden overcrowded with small shrubs planted randomly among the trees, and a wood picket fence replacing the original iron posts and chains.[35] Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. noted these changes in The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table, published in 1858 just as demolition was underway: “There were the shrubs and flowers in the Franklin-Place front-yards or borders; Commerce is just putting his granite foot upon them.”[36]

The Tontine Crescent and the other houses in Franklin Place were acquired by the city “for the public convenience”[23] and razed in 1858 to make way for blocks of large stone stores and granite warehouses in Franklin Street.[37] These buildings, along with a single elm remaining from the garden (plus three empty circular pits that once held trees), were destroyed in the Great Boston Fire of 1872.[38] The graceful curve and unusual width of Franklin Street today below Hawley Street are reflections of the Crescent’s ground plan. Architectural descendants include the Sears Crescent near today’s Boston City Hall and the façade of the Kirstein Business Branch of the Boston Public Library (built 1929-30), which replicates the entire central portion of the Tontine. Despite residents’ general aversion to connected structures, hundreds of brick row houses in the area draw inspiration from the Bulfinch structure, including Worcester and Chester Squares in the South End; West Hill Place and Charles River Square on Beacon Hill; a set of fifteen attached brick and half-timbered town houses on Elm Hill Avenue in Roxbury Highlands originally called Harris Wood Crescent; and a block of fifteen red-brick connected houses on Beacon Street in Brookline, built in 1907.[39]

An economic downturn meant that subscriptions came too slowly to meet bills, and Bulfinch went bankrupt in January 1796, turning from a comfortable situation as a gentleman concerned with architecture to a laborious life of architectural practice and public service. Financial troubles continued to plague him, such that he spent July 1811 in debtors’ prison, but the Crescent and Franklin Place helped transform Boston from an 18th-century town into a 19th-century city.[40]

Notes

- ↑ Whitehill, Walter Muir and Kennedy, Lawrence W. Boston: A Topographical History, p. 53. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2000.

- ↑ Roth, Leland M. A Concise History of American Architecture, p. 60. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1979, ISBN 0-06-430086-2.

- ↑ Maddex, Diane and Lewis, Roger K. Master Builders: A Guide to Famous American Architects, p. 20. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 1996, ISBN 0-471-14402-9.

- ↑ Goodman, Phebe S. The Garden Squares of Boston, p. 31. UPNE, 2003, ISBN 1-58465-298-5.

- ↑ Contrast with the traditional English leasehold system, in which buyers purchased houses already built by speculative builders and then signed leases with the estate owner.

- ↑ Colubian Centinel, July 31, 1793.

- ↑ Columbian Centinel, December 4, 1793. While the houses were complete by autumn 1794, apparently the last were sold in 1796, the sale being delayed by Bulfinch’s bankruptcy.

- ↑ Bulfinch, Ellen Susan (ed.). The Life and Letters of Charles Bulfinch, p. 99. Boston, 1896.

- ↑ The Circus (begun 1754) and the Royal Crescent (begun 1767).

- ↑ Whitehill and Kennedy, p. 53.

- ↑ Goodman, pp. 26-7.

- ↑ Pemberton, Thomas. A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston, 1794, p. 250. Boston: 1794.

- ↑ Leading through toward Summer Street, the arch gave origin and name to Arch Street.

- ↑ In all, then, these were four-story houses: two residential floors, a basement, and an attic.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goodman, p. 29.

- 1 2 Goodman, p. 27.

- ↑ A material that was a relatively new innovation for Boston dwellings of the period.

- ↑ Stone was not easily available and consequently very costly; when the Middlesex Canal of 1803 made Chelmsford granite accessible, Bulfinch began at once to use it in his work. Shand-Tucci, p. 11. However, he was also inspired by the painted stucco over brick examples he had seen in London. Goodman, p. 30.

- ↑ Asher Benjamin. Practice of Architecture, preface. Boston, 1833.

- ↑ Massachusetts Magazine, VI (February 1794), p. 67.

- ↑ Founded 1792; room given 1796.

- ↑ Founded 1791; room given 1794.

- 1 2 Goodman, p. 35.

- ↑ Jeremy Belknap’s sketch of September 20, 1794, shows the completed Tontine Crescent but gives no indication of building on the north side of Franklin Place. The sketch is in Belknap to Ebenezer Hazard, same date, Belknap papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

- ↑ Pemberton, p. 250.

- ↑ C. A. Place. Charles Bulfinch: Architect and Citizen, p. 64. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 1968.

- 1 2 Goodman, p. 32.

- ↑ Still, perhaps because it was so tiny, it was never mentioned in advertisements for the crescent houses; unlike in London, where the garden was the main selling point, here it was the houses’ architectural style. Goodman, p. 31.

- ↑ In theory, the deeds reserved the garden "for the accommodation, convenience and beauty" of residents alone, but this was not de facto the case. Goodman, pp. 31-2.

- ↑ At Goodman, p. 31.

- ↑ Goodman, pp. 33-4.

- ↑ Boston Women’s Heritage Trail,

- ↑ Goodman, p. 33.

- ↑ Shand-Tucci, Douglass. Built in Boston, pp. 86, 100. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999, ISBN 1-55849-201-1.

- ↑ Goodman, p. 34.

- ↑ Chapter 11

- ↑ Whitehill and Kennedy, pp. 129, 131.

- ↑ Goodman, p. 36.

- ↑ Morgenroth, Lynda. Boston Firsts, p. 110. Boston: Beacon Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8070-7132-3.

- ↑ Whitehill and Kennedy, pp. 54-5.

References

- Goodman, Phebe S. The Garden Squares of Boston, pp. 25–35. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2003, ISBN 1-58465-298-5.

- Kirker, Harold. The Architecture of Charles Bulfinch, pp. 78–81, 89-90. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1969.

- Kostof, Spiro (1985). A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 619–620. ISBN 0-19-503472-4.

Coordinates: 42°21′19.57″N 71°3′28.89″W / 42.3554361°N 71.0580250°W