Francisco Martín Melgar y Rodríguez

| Francisco Melgar Rodríguez | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Francisco Melgar Rodríguez 1849 Madrid |

| Died |

1926 Paris |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | journalist |

| Known for | politician, author |

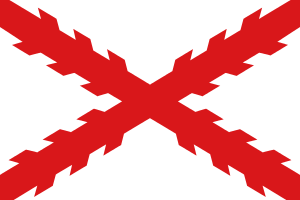

| Political party | Carlist |

Francisco de Asís Martín Melgar y Rodríguez Carmona, 1. Count of Melgar del Rey (1849-1926), was a Spanish Carlist politician. He is known as political secretary of the Carlist king Carlos VII and one of the late 19th century party leaders. He is also noted as author of memoirs, which together with his massive personal archive are invaluable source on Carlist history of the era.

Family and youth

The Melgar family originated from Aragon. Francisco’s paternal grandfather, Jorge Martín Melgar, left his native Zaragoza and settled in Madrid.[1] His son and Francisco’s father, Manuel Martín Melgar (1806-1883),[2] already as a young man grew to low-range administrative positions at the court; in 1827 he was nominated fiscal in Real Academia de Teologia[3] and in 1831 he became Bibliotecario de Cámara of Francisco de Paula, the youngest brother of Fernando VII.[4] He remained loyal to Infante Francisco during the First Carlist War, in the 1840s passing to entourage of his vehemently liberal son, Infante Enrique.[5] In 1848 confirmed as royal secretary,[6] during década moderada he broke with the court following political disagreements.[7] He dedicated himself to law career[8] and acted as representative of local Madrid Catholic establishments, retaining the honorary title of secretario primero del gobierno.[9] Over time Manuel Melgar assumed an increasingly conservative stand; in the 1860s he approached the neocatólicos, together with them nearing the Carlists later on. In 1870 he became vice-president of the Madrid Junta Provincial Católico-Monarquica,[10] a Carlist-dominated grouping.[11]

Manuel Melgar was married three times,[12] in 1848 with a Valenciana, María del Carmen Rodriguez Carmona.[13] It is not clear how many children the couple had: different sources suggest there might have been three[14] of five[15] siblings. Francisco was born as the second oldest son,[16] all raised in fervently Catholic ambience.[17] None of the sources consulted provides information where he received his childhood and early teen education. In 1864 he entered Universidad Central and pursued a double curriculum, studying both at Facultad de Filosofia y Letras and at Facultad de Derecho.[18] During his academic years he was exposed mostly to Liberal thought of his professors, like Castelar, Montero, Salmerón and Moret,[19] though he forged friendship with conservatively minded students like Enrique de Aguilera, the future marqués de Cerralbo.[20] He graduated in 1868 in both law and letters.[21]

Family life of Francisco Melgar remains rather obscure; neither he in his memoirs nor any of the scholars offers any meaningful insight into his personal matters. Next to nothing is known about his wife, Mme Trampus,[22] except that according to Melgar[23] she was mentally ill and developed maniac behavior.[24] Neither her nationality[25] nor date of the marriage is clear; their daughter, Carmen Melgar Trampus, became a nun[26] and their son, Francisco Carlos Melgar Trampus, was born as late as 1903.[27] As a youngster serving as secretary to the Carlist claimant Don Jaime,[28] he engaged in Madrid Carlist structures of the 1920s;[29] in the 1930s he was the Paris correspondent of Estampa and As,[30] in the 1940s active in the Francoist press; in the 1950s he acknowledged Don Juan as legitimate Carlist heir and entered his Consejo Privado.[31] Author of a few books on Carlism,[32] in the 1960s he wrote as a columnist to ABC.[33] His son, Jaime Melgar Botassi, worked as translator.[34] Currently the condado rests with Francisco’s great-grandson, Francisco Melgar y Gómez de Olea Botassi y Naveda.[35]

Early Carlist engagements

Inheriting late conservative outlook of his father, Melgar engaged in a number of initiatives confronting secular tide of the 1868 Glorious Revolution. In 1869 he was among founders of La Armonia,[36] a cultural society promoting Catholic orthodoxy as the backbone of public education.[37] The same year he co-founded Juventud Católica[38] and become treasurer of its Junta Superior,[39] apart from engaging in other confessional bodies.[40] He mixed with neocatólicos, tended to side with Nocedal in controversies with the Carlist claimant Carlos VII[41] and by some scholars is considered a neo himself,[42] but in his later years Melgar spoke about the Neo-Catholics with disregard if not sheer contempt.[43]

In the late 1860s Melgar, from his youth demonstrating impressive ease of writing, commenced co-operation with a number of Madrid right-wing periodicals[44] and befriended Traditionalist pundits of the era, like Francisco Navarro Villoslada, Antonio Juan de Vildósola and Candido Nocedal;[45] with Antonio Aparisi Guijarro he was even distantly related.[46] Formally member of the editorial board of El Pensamiento Español,[47] in 1871 he became key staff member of La Reconquista.[48] Upon the 1872 outbreak of the Third Carlist War Melgar became editor-in-chief of the paper;[49] increasingly endangered by Republican hit-squads dubbed "partido de la porra", he went into hiding.[50] In 1873 he took part in gathering of Carlist press leaders in Bordeaux, where Melgar met the claimant for the first time.[51] Having returned to Madrid he went on editing La Reconquista until it became impossible, in 1874 leaving by sea[52] for the Carlist zone.[53]

Carlos VII entrusted Melgar with setting up an official Carlist bulletin, which materialized in Tolosa as El Cuartel Real. Managed, edited if not mostly written by Melgar, it kept appearing until few days before the city fell to the Alfonsist troops in 1875.[54] He later joined 2. Gipuzkoan Battalion.[55] His older brother was mortally wounded in action,[56] but it is not clear whether Francisco took part in combat; according to some sources he fought in last battles of the war.[57] He then survived mutiny of the unit[58] and in February 1876 crossed the Pyrenees into France,[59] breaking his rifle upon leaving the country.[60]

Melgar’s father due to his support lent to the Carlists[61] was expropriated[62] and chased by the security;[63] he settled on exile in Sant-Jean-de-Luz,[64] but Francisco did not join him. Also wanted by the Madrid government,[65] he decided to live in Paris. Resuming journalist career he became the press correspondent; apart from foreign periodicals,[66] under pen-names he contributed also to the Spanish ones.[67] According to himself, he declined the offer by Pidal and Moret, who first invited him to assume the job of director of Biblioteca Nacional and than suggested he becomes first secretary of the Spanish embassy in Paris.[68] When Carlos VII returned from his international voyages and settled in Paris late 1877,[69] the two resumed contact. As the claimant’s political secretary, Emilio Arjona y Laínez, was getting increasingly unpopular among the Carlists,[70] Melgar started to act as his provisional replacement.

Political secretary: service to Carlos VII

In 1880 the French authorities expulsed Carlos VII.[71] Asked by the claimant to become his official secretary,[72] Melgar agreed.[73] The two men[74] settled in Venice in the building known as Palazzo Loredan; while Don Carlos and his family[75] occupied the upper floor, Melgar lived on the lower level.[76] Except that Melgar maintained duly respectful position towards his king, the two remained on cordial terms;[77] when travelling, they even shared the same servant.[78] Don Carlos appreciated Melgar’s service and in 1888 conferred upon him condado de Melgar del Rey,[79] recognized by the Madrid government in 1956.[80] Though in the late 1890s the relationship deteriorated, it remained friendly until the very end; Carlos VII used to address his subject as "Melgarito".[81] The job was fully paid; apart from having his daily expenses covered, Melgar was receiving a monthly salary.[82]

The key Melgar’s task was to run massive correspondence of the claimant.[83] He also accompanied the king in voyages across Europe[84] and the world,[85] and participated in political gatherings.[86] Granted significant autonomy, after the Integrist breakup in 1888 Melgar became key link in the party command chain, described as Carlos VII – Melgar – Cerralbo.[87] Exact scale of his impact on party politics is not clear. Though Carlos VII sought his advice on many issues,[88] it is unlikely that Melgar exercised major influence on the charismatic Carlist king; students underline rather his genuine devotion to the monarch.[89] It is because of the autonomy he enjoyed that some refer to him as one of key Carlist leaders of the late 19th century, member of the inner-circle ruling the movement.[90]

When discussing Melgar’s term as political secretary historians usually present him as a "cerralbista", supporter of non-belligerent, moderate, aperturista policy of his old-time friend de Cerralbo.[91] This stand was demonstrated in the 1880s, during growing conflict with the Nocedals,[92] and in the 1890s, during Carlist attempts to re-enter official political life in Spain.[93] Melgar is hardly presented as a theorist;[94] he is rather portrayed as an intriguer, a person who thrived plotting Machiavellian personal schemes; apart from minor personal decisions,[95] some suggest he might have unfairly contributed to the 1888 Integrist secession[96] and note that he was involved in beginnings of the conflict with Juan Vázquez de Mella.[97]

Melgar’s position started to change in 1894; he found himself in acute personal conflict with the newly wed second wife of Carlos VII, Berthe de Rohan.[98] Relations between the king and his secretary worsened in unclear circumstances during Carlist military buildup of 1898-1900.[99] Though Melgar was probably aware of belligerent preparations taking place beyond party structures[100] he did not push for insurgency.[101] Its uncontrolled outbreak in October 1900 caught Carlist leaders by surprise. The claimant, outraged and suspicious, decided to purge the party executive, with both Cerralbo and Melgar falling victims.[102] According to himself, he was sacked as a result of joint intrigue of general Moore and Berthe de Rohan.[103] Some scholars suggest that Carlos VII considered him traitor,[104] but Melgar underlined cordial farewell he received in November 1900.[105]

Unofficial secretary: service to Jaime III

Having promised on departure[106] that during his king’s lifetime he would neither settle in Spain[107] nor re-enter politics,[108] Melgar returned to Paris[109] and resumed his never entirely abandoned career of a press correspondent;[110] he also maintained private links with some Carlist politicians.[111] His fortunes changed in 1909, when Carlos VII passed away and the Carlist claim to the throne was assumed by his son, Jaime III. The new king since his early childhood was used to constant Melgar’s presence.[112] Also during his adolescence the relations between the two were very good; the prince appreciated that when in love with Mathilde of Bavaria, Melgar supported the marriage plans, eventually cancelled by opposition of his father and especially stepmother.[113] In 1910 Melgar was invited to Don Jaime’s residence in Frohsdorf,[114] where during a few months of stay their relationship was refreshed and enlivened; apparently Melgar helped Don Jaime to sort out paperwork, partially inherited from his late father and partially related to his own ascendance to the throne.[115]

From that moment Melgar resumed duties of political secretary and partially advisor[116] to the Carlist king, to some degree again acting in-between the monarch and Carlist politicians in Spain.[117] However, format of the service was somewhat different compared to the 1880-1900 period. It was carried out on de facto[118] rather than formal basis, it was periodical and occasional rather than systematic and until 1919 it was performed remotely,[119] though when Don Jaime settled in Paris, the two resumed close direct personal links.[120] Another key difference was that unlike his father, Jaime III used to go into long periods of inactivity, which permitted Melgar to exercise more personal influence on party politics. On the other hand, similarly to the first spell of Melgar’s activity also the second one was marked by intrigues and personal schemes.

.jpg)

Carlist politics of the 1910s developed mostly as a conflict between the key party theorist, Juan Vázquez de Mella, and the claimant. Already in the 1890s highly skeptical of de Mella, since 1910 Melgar was waging a secret guerilla war against him.[121] A carefully crafted plot intended to compromise de Mella[122] backfired and in 1912 the Mellistas were reinstated in the Carlist Spanish executive;[123] at that time de Cerralbo, increasingly under the influence of de Mella, was already approached by Melgar with well camouflaged hostility.[124] Around the same time Melgar was also engaged in unclear maneuvers which by some scholars are interpreted as vaguely testing a possibility of enforcing Don Jaime’s abdication in favor of his uncle, which would probably leave the party in hands of Cerralbo and Melgar.[125] He went on confronting the Mellistas;[126] posing as Cerralbo’s friend he provoked his 1913 resignation.[127] In the same document Cerralbo suggested that Melgar replaces him as royal representative in Spain,[128] but the question proved pointless as the resignation was not accepted by the king.[129]

Political climax and demise

During the First World War Melgar emerged as leader of minoritarian aliadófilo faction within Carlism;[130] apart from having been a longtime French resident, he also witnessed dynastically motivated ice-cold relations between Carlos VII and Franz Joseph, developing particular enmity towards the Austrian kaiser and the Central Powers.[131] Some scholars suggest that already upon the outbreak of hostilities in the summer of 1914 Melgar’s advice cost Don Jaime dearly. Personally sympathizing with the Entente but officially pursuing a neutral path, when asked by the Austrians for vague declaration of loyalty Don Jaime remained adamant, which led to his house arrest in Frohsdorf.[132] This was probably not intended by Melgar, though as a result the claimant remained hardly contactable during the next 4 years of warfare, in turn leaving Melgar almost free to deal with the party executive back in Spain.

When confronting the pro-German Mellistas Melgar resolved to provocations[133] but mostly embarked on massive Gallophile[134] propaganda. His pamphlets, designed either for Spanish[135] or foreign[136] audience, advanced all sort of arguments against the Central Powers, lambasting their Carlist supporters as "carlo-luteranos"[137] and mocking their slogan as "Dios, Patria, Alemania".[138] In 1916 he considered setting up a pro-French daily in Madrid[139] and possibly appeared in Spain himself.[140] He might have misled de Cerralbo as to actual position of the claimant.[141] In 1917-1918 he was increasingly ostracized among the Carlists.[142] When in early 1919 Don Jaime managed to leave Austria and arrived in Paris, his first step was consulting Melgar before he released a manifesto – allegedly written by Melgar[143] – which announced forthcoming personal measures against those deemed disloyal.[144] De Mella and his followers intended to show up in the French capital and present their case but were denied visas, a Machiavellian intrigue also attributed to Melgar.[145] The Mellistas, who already considered Don Jaime "a toy of Melgar",[146] gave up and decided to break away, setting up their own party; Cerralbo resigned.

Following the breakup Melgar focused on purging the party newspaper from the Mellistas;[147] as he remained a lone player and did not build his own political background, the term "Melgaristas" was scarcely in circulation.[148] When the new provisional party leader Pascual Comín was to be replaced in the summer of 1919, Don Jaime asked Melgar to become his representative in Spain, but the 70-year-old refused,[149] probably conscious that in the party feelings against him were running high. As demands to get rid of Melgar reached the claimant he realized this as well; Melgar was not invited to take part in Magna Junta de Biarritz, a grand Carlist assembly entrusted with working out the Carlist course into the future.[150] Starting 1920 he is no longer mentioned as acting in-between the claimant and the party leadership, though some sources claim that until the mid-1920s he served as secretary and counselor to his king,[151] in 1923 replaced by own son.[152] Since 1914 Melgar suffered from limited financial resources;[153] according to one source he spent his last years in poverty.[154]

Author and publisher

Brought up in the family of a librarian, already during his juvenile years Melgar demonstrated a knack for letters. In the late 1860s he won laurels in poetry: selected by authors like Aureliano Fernández-Guerra y Orbe and Manuel Tamayo y Baus, he was awarded literary prize for his poem dedicated to the First Vatican Council.[155] In the press and almanacs of the era he sporadically published poems, grandiose in style and revolving around religious topics,[156] though he also translated works of religious French authors like Enrique Lasserre.[157] In the 1870s he was known as "poeta y periodista Melgar", like in case of the 1873 reference of Alejandro Pidal.[158]

In the early 1870s he focused on typical press work, contributing to El Pensamiento Español, La Esperanza, La Convicción, Altar y Trono and La Ciudad de Dios.[159] Most items identified seem to be minor editorial pieces,[160] though it is not clear if and what pen-names Melgar might have used, especially when running La Reconquista. In the late 1870s as "Franco de Sena" he kept supplying correspondence from Paris to La Illustración Católica,[161] El Siglo Futuro[162] and the Santiago de Chile based El Estandarte Católico,[163] covering the Spanish issues for the French L’Univers and L’Chiven.[164] In the 1880s and 1890s as "Marcos Laguna" or "Monsieur le Comte"[165] he contributed to El Correo Español[166] and El Estandarte Real,[167] later writing also to La Hormiga de Oro.[168] Until death he remained the correspondent of La Epoca.[169]

Melgar’s works which stirred most controversy are his pro-Entente pamphlets from 1916-1917, mostly En desgravio, La mentira anónima and La gran víctima.[170] Written with partisan zeal and propagating all sorts of calumnies against the Central Powers, they turned many Carlists against Melgar,[171] though it is not clear how many Spaniards they won for the cause of the Allies. They were certainly noted abroad; the British New Statesman acknowledged them as "amazing pamphlets".[172] Today they are considered "classic example of the surrender of objectivity" and virulent propaganda.[173]

Melgar is best known as author of memoirs; written in the mid-1920s and titled Veinte años con Don Carlos, they were published by his son in Madrid in 1940.[174] The 220-page book covered only the years when Melgar served as political secretary of Carlos VII; lively narrated it is singularly uninformative as to details of his work, though it projects all personal preferences and dislikes of the author. Aversion towards theoretical and ideological debates combined with abundant gossip and picturesque anecdotes make it excellent read; some historians warn that it must not be approached as literally accurate and even suspect manipulation,[175] others generally consider it a fairly reliable source.[176] Another book published by Melgar Trampus in 1932, Don Jaime el principe caballero, most likely is co-work of the father and the son; it appeared under ambiguous name of "Francisco Melgar", attributable to both.[177] In historiography Melgar is most appreciated for his massive private archive, which in absence of destroyed private papers of Carlos VII provides excellent insight into the Carlist history of the era.[178]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Matias Fernández García, Parroquias madrileñas de San Martín y San Pedro el Real: algunos personajes de su archivo, Madrid 2004, ISBN 9788487943997, p. 134

- ↑ El Siglo Futuro 05.03.83, available here

- ↑ Guía de litigantes y pretendientes 1827, p. 18, available here

- ↑ Colección Legislativa de España. Consejo de Estado, Madrid 1884, p. 797, available here

- ↑ Jules Antoine Taschereau, Revue rétrospective, ou, Archives secrètes du dernier gouvernement [1830-1848]: recueil non périodique, Paris 1848, p. 462, available here

- ↑ Guía de forasteros en Madrid 1850, p. 246, available here

- ↑ Diario de las sesiones de Cortes 1850, p. 272, available here

- ↑ Jurisprudencia civil: colección completa de las sentencias dictadas por el Tribunal Supremo en recursos de nulidad, casación civil é injusticia notoria y en materia de competencias desde la organización de aquéllos, Madrid 1871, pp. 260-261, available here, also Sentencias del Tribunal supremo de justicia vol. 2, Madrid 1873, p. 556, available here

- ↑ in 1865 he was active as secretary of Sacramental de San Isidro, San Pedro, San Andrés y Ánimas Benditas, see La Esperanza 14.09.66, available here

- ↑ La Regeneración 01.07.70, available here

- ↑ by some plainly named Carlist, see B. de Artagan [Reynaldo Brea], Políticos del carlismo, Barcelona 1912, p. 57

- ↑ he was first married to Josefa Rodríguez, then to María del Carmen Rodriguez and finally to Josefa Hernandez. According to one source, Francisco was born to Manuel Martín Melgar and Josefa Hernandez (not María Rodriguez), which appears to be either a mistake or a very odd case, Fernández García 2004, p. 134

- ↑ along her paternal line she was also related to Aragon, daughter of Manuel from Zaragoza and María Carmen from Valencia, Fernández García 2004, p. 134

- ↑ Fernández García 2004, p. 134

- ↑ named Ventura and Concepcción, El Siglo Futuro 05.03.83

- ↑ after Manuel, born 1832, Fernández García 2004, p. 134

- ↑ "familia de arraigados sentimientos católicos", Francisco de Paula, Album de Personajes Carlistas con sus Biografias, volume II, Barcelona 1888, vol. 2, p. 203

- ↑ Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922): biografía politica [PhD thesis], Madrid 2012, p. 25

- ↑ Francisco Melgar, Veinte años con Don Carlos. Memorias de su secretario, Madrid 1940, p. 8

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 25

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 26, Melgar 1940, pp. 7-8

- ↑ in one of his private letters Melgar made an obscure and mysterious confession that "por ese bien [of Spain] me resuelvo al horrendo sacrificio de casarme", Juan Ramón Andrés Martín, El caso Feliú y el dominio de Mella en el Partido Carlista en el período 1910-1912, [in:] Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie V: Historia Contemporánea 10 (1997), p. 108

- ↑ one scholar claims that Melgar was misogynic, as in his memoirs he bemoaned, apart from his own wife, also the wife of Ramón Nocedal and Berthe de Rohan, Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 99–100. This claim should be approached with caution, as his memoirs contain also a very warm and friendly portrait of Doña Margarita de Borbón-Parma

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 448

- ↑ apart from the US, currently the name is recorded mostly in the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, close to Venice where Melgar lived in 1880-1900, compare namespedia service

- ↑ ABC 10.02.71, available here

- ↑ see Melgar, Francisco (1903-1971) entry [in:] datos.bne service, available here

- ↑ Mundo Gráfico 31.01.23, available here

- ↑ leading the Madrid branch of unofficial Carlist "La Protesta" movement in the 1920s, Jordi Canal, El carlismo. Dos siglos de contrarrevolución en España, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788420639475, p. 285

- ↑ mostly fashion, leisure and especially sports correspondence, compare As 28.01.35, available here or Estampa 18.03.33, available here

- ↑ ABC 13.12.56, available here

- ↑ especially Pequeña historia de las guerras carlistas (Madrid 1958) and El noble final de la escisión dinástica (Madrid 1964)

- ↑ ABC 09.12.66, available here, ABC 04.06.66, available here

- ↑ and was 3. count of Melgar del Rey, see Boletín Oficial del Estado 05.05.73, available here

- ↑ who is 4. count of Melgar del Rey, see Boletín Oficial del Estado 22.01.83, available here

- ↑ Antonio Jiménez-Landi, La Institución Libre de Enseñanza y su ambiente: Los orígenes de la Institución, Barcelona 1996, ISBN 9788489365964, p. 197

- ↑ Begoña Urigüen, Orígenes y evolución de la derecha española: el neo-catolicismo, Madrid 1986, ISBN 8400061578, 9788400061579, pp. 215-6

- ↑ "academia científico-literaria, compuesta exclusivamente de jóvenes católicos resueltos a defender la unidad reliriosa en España, cualesquiera quesean las opiniones meramente políticas que cada uno profese", José Andres Gallego, La politica religiosa en España, Madrid 1975, pp. 14, 45

- ↑ Urigüen 1986, p. 365

- ↑ he was member of Claustro de Profesores de los Estudios Católicos en Madrid in facultad de derecho as auxiliar, Urigüen 1986, p. 568

- ↑ Urigüen 1986, p. 495

- ↑ Víctor Manuel Arbeloa Muru, Clericalismo y anticlericalismo en España (1767-1930): Una introducción, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788499205489, p. 277

- ↑ except Candido Nocedal, whom he respected and admired, Melgar 1940, pp. 9-10

- ↑ Artagan 1912, p. 57, Melgar 1940, p. 9

- ↑ Melgar 1940, pp. 8-9

- ↑ Aparisi’s brother’s son, Francisco, was married first to Melgar’s maternal aunt, and than to his own sister, Melgar 1940, p. 9

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 8

- ↑ Artagan 1912, p. 57

- ↑ its original editor-in-chief, Valentín Gómez, was detained, Melgar 1940, p. 10

- ↑ Urigüen 1986, p. 460

- ↑ Melgar 1940, pp. 11-12

- ↑ in 1874 the security was closing on him; feeling he would soon be located, Melgar took the train to Santander and by sea arrived in Saint-Jean-De-Luz, from where he crossed to the Carlist-controlled zone, Melgar 1940, p. 28

- ↑ there is a somewhat confusing but very picturesque account which probably refers to Francisco joining the Carlist troops: "Pasaba yo una tarde por delante del 2. de Castilla cuando de un grupo de voluntarios vinieron dos muy jôvenes à saludarme. Trabajo me costo reconocerlos pero luego me halle en elles à los hermanos de dos amigos mios: llamase el uno Benigno Sanchez de Castro; el otro Manuel Martin Melgar, y àmbos no tenian aùn pelo de barba ni la estatura necesaria para ser soldados. Hijos los dos de famílias acomodadas, acostumbrados à la vida sosegada de su casa y sin haber jamás carecido de nada, estaban cuando les encontres que era en invierno, vestidos con una sencilla blusa de pafio gris como uniforme, rotos, sùcios y con senales évidentes de baber andado mucho. — Qué haceis aqui, les pregunté, que sois? — Somos, me contestaron, cadetes del 2. de Castilla, y hacemos lo que cualquier soldado. — Y podeis con el fusil? les dije viendo los allens que tenian al lado casi tan grandes como elles. — Al principio, me contesto Melgar, que era el ménos robuste, nos costaba trabajo llevarlos, pero ahora andamos perfectamente con el fusil, la mochila y 80 cartuchos, y hacemos largas marchas sin cansarnos", Francisco Hernando, Recuerdos de la Guerra Civil: La Compaña Carlista, 1872 à 1876, Paris 1877, available here. It might appear that the passage refers to Manuel, who indeed served in the Castillan battalion; however, at that time he was in his late 30s; physical description fits rather Francisco, then in his early 20s

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 29

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 30; according to Artagan 1912, pp. 57-8 it was Batallón 4. de Guipúzcoa

- ↑ Manuel Martín Melgar served in Batallón 2. de Castilla, fought at Somorrostro, rose to teniente and was mortally wounded at Mercadillo, passing away in the Valmaseda hospital few days later, Artagan 1912, p. 57

- ↑ himself he claims to have taken part in an unidentified "battle of Mandigorotz", Melgar 1940, pp. 29-30

- ↑ Carlist soldiers of the 2. Gipuzkoan battalion mutined on their way to the French border and returned to surrender and get financial reward promised by the Madrid government, killing on their way the Carlist Gipuzkoan military commander who tried to stop them, Melgar 1940, pp. 29-30

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 30-31

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 33. It is not clear whether he has ever returned to his home country. A single source (ABC, though on its humour pages) claims he did in 1917, see ABC.24.03.17, available here

- ↑ La Discussión 17.07.1873, available here

- ↑ La Correspondencia de España 17.07.75, available here

- ↑ Diario Oficial de Avisos de Madrid2016.01.81, available here

- ↑ "estuvo preso, fué perseguido y desterrado con su mujer y sus hijos, en ocasión y con circunstancias angustiosísimas; y en el destierro ha muerto sufriendo las consecuencias de tantas y tan duras persecuciones", El Siglo Futuro 05.03.83, available here

- ↑ Diario Oficial de Avisos de Madrid 19.01.77, available here

- ↑ Región 06.03.26, available here

- ↑ Región 06.03.26, Raquel Arias Durá, Revista "La Hormiga de Oro". Análisis documental, [in:] Revista General de Información y Documentación 24-1 (2014), p. 40, compare La Illustración Católica 21.03.79, available here

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 86-7, also Jordi Canal i Morell, El carlisme català dins l’Espanya de la Restauració: un assaig de modernització politica (1888–1900), Barcelona 1998, ISBN 9788476022436, p. 27

- ↑ the Carlist king settled in Passy (a district in 1860 incorporated within the city limits), in a hotel located at Rue de la Pompe 49 (the building currently non-existent, demolished when constructing Rue de Siam), Melgar 1940, p. 38; detailed discussion in Jordi Canal, Incómoda presencia: el exilio de don Carlos en París, [in:] Fernando Martínez López, Jordi Canal i Morell, Encarnación Lemus López (eds.), París, ciudad de acogida: el exilio español durante los siglos XIX y XX, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788492820122, pp. 85-112

- ↑ Melgar 1940, pp. 12-3

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 38. According to other sources Carlos VII was expulsed in 1881 and settled in Venice in 1882, Canal 2010, p. 112

- ↑ some scholars refer to his role as "secretario personal" - Eduardo González Calleja, La razón de la fuerza: orden público, subversión y violencia política en la España de la Restauración (1875-1917), Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788400077785, p. 191 or "secretario particular" - Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 325; Melgar himself uses the term of "secretario político", Melgar 1940, p. 215

- ↑ Artagan 1912, p. 58, Canal 1998, p. 88; previous secretaries included Navarro Villosalda (acted briefly as he soon broke his leg - Carlos Mata Induráin, Siete cartas del conde de Melgar a Navarro Villoslada (1885-1886), [in:] Príncipe de Viana 213 (1998), p. 308) and Antonio Aparisi - Melgar 1940, p. 149

- ↑ when dwelling on his 20-year-long stay in Venice Melgar always refers to himself only, except one reference to brief and temporal stay of his mother, Melgar 1940, p. 223. Carlos VII settled in Venice without his wife; doña Margarita de Borbón-Parma upon leaving Paris in 1880 decided to settle in her residence in Viareggio and lived there until her death in 1893

- ↑ their children lived in Venice and Viareggio on the on-and-off basis

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 160

- ↑ though not really intimate; Melgar – at least according to himself - refused to enter quasi-familiar relations, see Melgar 1940, pp. 57-8

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 67

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 25

- ↑ Boletín Oficial del Estado 13.12.56, available here

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 208

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 486

- ↑ except private family correspondence Carlos VII wrote letters personally only in specific cases, usually to demonstrate his personal respect

- ↑ also in case of claimant’s family affairs, e.g. when attending 1882 first communion of Don Jaime in England, see Bernardo Rodríguez Caparrini, Alumnos españoles en el interado jesuita de Beaumont (Old Windsor, Inglaterra), 1888-1886, [in:] Hispania Sacra 66 (2014), pp. 417 and onwards

- ↑ Carlos VII undertook 2 major trips in the 1880s: in 1884-5 to Africa (Egypt) and Asia (India, Ceylon, Goa) - Melgar 1940, p. 124, in 1887 to America (Haiti, Barbados, Jamaica, Panama, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Uruguay, Argentina) - Melgar 1940, pp. 136-147; in the 1890s following marriage with Berthe de Rohan he travelled in 1894-5 to Egypt and Palestine - Melgar 1940, p. 196

- ↑ e.g. in 1896 Melgar participated in the Loredan gathering, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 325

- ↑ Canal 1998, p. 88; it was Melgar who in 1876 introduced Cerralbo to Carlos VII, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 26

- ↑ e.g. when asked to provide his opinion on two most powerful regional leaders, Tirso de Olazabal and Luis de Llauder; Melgar claimed they were dangerously leaning towards Nocedal and suggested they were called for some time to Venice to get things straight; the advice indeed followed later on, Melgar 1940, p. 151

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 84, 181

- ↑ Jordi Canal i Morell, Las "muertes" y las "resurrecciones" del carlismo. Reflexiones sobre la escisión integrista de 1888, [in:] Ayer 38 (2000), p. 118, Canal 1998, p. 83, Jacek Bartyzel, Nic bez Boga, nic wbrew tradycji, Radzymin 2015, ISBN 9788360748732, p. 309

- ↑ Jordi Canal i Morell, La revitalización política del carlismo a fines del siglo XIX: los viajes de propaganda del Marqués de Cerralbo, [in:] Studia Zamorensia 3 (1996), p. 245; until the early 20th century there were only minor controversies between Melgar and Cerralbo, compare Agustín Fernández Escudero, El XVII Marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922). Iglesia y carlismo, distintas formas de ver el XIII Centenario de la Unidad Católica, [in:] Studium: Revista de humanidades 18 (2012) p. 132

- ↑ already in 1881 Melgar was engaged in a plot to remove Nocedal, Canal 1998, p. 47, for later years see Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 55. He held bad opinion about Ramón Nocedal also later, see Melgar 1940, p. 148

- ↑ e.g. he co-ordinated setting up a new orthodox Carlist daily, El Correo Español, Canal 1998, p. 135, Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 134-138, and was engaged in building party structures, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 140 and onwards

- ↑ when laid out, his views have the charm of being rather simple, e.g. he characterised the credo of Canovas as "Rey, Dios, Patria"; also his vision of Carlism was rather simple, based on religion, monarchy and dynastical loyalty, with no mention about traditional heritage, fueros, organic society etc, compare Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 181. Similarly, the Integrist breakup is explained in simple, personal terms, Melgar 1940, pp. 148-154

- ↑ e.g. dismissal of prince de Valori, until 1892 the official Carlos VII’s representative in France, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 276

- ↑ Jaime de Carlos Gómez-Rodulfo (ed.), Antologia de Ramón Nocedal y Romea, Madrid 1952, p. 12, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 63, Javier Real Cuesta, El Carlismo Vasco 1876-1900, Madrid 1985, ISBN 9788432305108, p. 88

- ↑ Melgar was critical of de Mella already in the early 1890s, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 130, Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista: historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8487863825, pp. 29-30

- ↑ whom he assessed as suffering from paranoia, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 307. Initially Melgar was in favor of the marriage, convinced that the king should re-marry, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 302, and was even present during the private wedding ceremony in Prague, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 304. In his later years Melgar described her as "fenómeno patológico y padecía, según supe después, de una extraña enferme dad que los médicos califican de "paranoia acutisima" y consiste en una irresistible tendencia a mentir sin objeto y sin necesidad las más de las veces, sólo por no decir la verdad", Melgar 1940, p. 179

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 351-4

- ↑ e.g. the 1899 conspiracy of Salvador Soliva, Jordi Canal, La violencia carlista tras el tiempo de las carlistadas: nuevas formas para un viejo movimiento, [in:] Santos Juliá (ed.), Violencia política en la España del siglo XX, Madrid 2000, ISBN 843060393X, p. 41

- ↑ he realized marginal chances of success and poor organization of the conspiracy, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 272

- ↑ according to one scholar he simply fell prey to internal strife within Carlism, Canal 1998, p. 301; another one claims he was fired "misteriosamente", Andrés Martín 2000, p. 37

- ↑ according to Melgar, general Moore presented him as sold to the Madrid government, Melgar 1940, p. 219. Bertha de Rohan presented him as conspiring to enforce abidcation of Carlos VII in favour of his son, Melgar 1940, p. 222 Canal 1998, p. 88

- ↑ Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXVIII-I, Sevilla 1959, pp. 260-266

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 401-408; officially he resigned due to health reasons - Andrés Martín 2000, p. 37

- ↑ Manuel Polo y Peyrolón was initially considered Melgar’s replacement as don Carlos’ secretary, but the plan did not work out. In 1900-1909 the post was held by a number of very different individuals: general Sacanel, general Medina, Eusebio Zubizarreta, Francisco Albalat, Julio Urquijo and others, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 406

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 221

- ↑ Andrés Martín 2000, p. 37

- ↑ Región 06.03.26

- ↑ in the 1880s and 1890s he contributed to El Correo Españpl and El Estandarte Real, Canal 1998, p. 77, El Siglo Futuro 06.06.89, available here, Artagan 1912, p. 120

- ↑ e.g. he maintained extensive correspondence with Polo y Peyrolon and in 1902 was visited in Paris by de Cerralbo, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 450

- ↑ e.g. Melgar was among those coming to Britain to attend Don Jaime’s first communion, Rodríguez Caparrini 2014, p. 417

- ↑ Melgar 1940, pp. 158-163

- ↑ Palazzo Loredan was already sold by Berthe de Rohan

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 425

- ↑ see e.g. 1912, when Don Jaime turned to Melgar for advice as to what policy he should adopt towards de Mella, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 439

- ↑ e.g. transmitting orders of Don Jaime in 1913 and 1914, Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 454-5, 473

- ↑ "secretario de facto", Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 460

- ↑ Don Jaime lived in Frohsdorf and Melgar lived and Paris; personal contact was maintained in course of brief visits, e.g. Melgar was in Frohsdord in 1913, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 474, while Don Jaime visited Paris from time to time

- ↑ some sources claim he was for 6 years secretary of Don jaime, which probably refers to the 1919-1926 period, ABC 04.06.66, available here. In the 1920s it was Melgar’s son briefly introduced to secretarial work, see Mundo Gráfico 31.01.23; apparently the co-operation did not work out and in the mid-1920s the young Melgar was already reported as active in Madrid, Canal 2000, p. 285

- ↑ in 1910 Melgar and Mella briefly stayed for few months in Frohsdorf and developed sincere mutual hatred; Melgar, vehemently loyal to the Carlist dynasty, suspected de Mella of playing down the dynastical threads of Carlist ideario, Andrés Martín 2000, p. 49

- ↑ the plot consisted of provoking de Mella into statements openly challenging Don Jaime’s legitimacy to govern, Andrés Martín 1997, pp. 68-70, 104-105, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 440. Initially Mella did not consider such an escalation, but eventually he fell into this trap, Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El caso Feliú y el dominio de Mella en el partido carlista en el período 1909–1912, [in:] Historia contemporánea 10 (1997), p. 109

- ↑ Andrés Martín 1997, pp. 107-9

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 450

- ↑ Andrés Martín 1997, p. 110

- ↑ especially struggling for control of Correo Español, Andrés Martín 2000, p. 76

- ↑ Melgar managed to convince Cerralbo that de Mella was pushing him towards the unpredictable, Andrés Martín 2000, p. 78

- ↑ the issue is not entirely clear. One author claims boldly that Cerralbo "proponia delegar todas sus responsibilidades en Melgar", Andrés Martín 2000, p. 78, while another suggest that Cerralbo was merely "proponiendo al conde de Melgar para que le sustituya en las reuniones con Llorens", Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 470

- ↑ and anyway Melgar did not seem prepared to take the task, Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 470-1

- ↑ Andrés Martín 2000, p. 106; most Carlists tended to sympathise with the Central Powers, either because they viewed the German and Austrian political models as closer to their vision, or because they sided against Britain, considered the primordial enemy; for detailed discussion see José Luis Orella, Consecuencias de la Gran Guerra Mundial en al abanico político español, [in:] Aportes 84 (2014), pp. 105-134

- ↑ kaiser’s sister was married to Alfonso XII and was queen-regent of Alfonso XIII; Franz Joseph a number of times hinted to Carlos VII that he expected no more activity undermining the rule of his sister, the most frank remark in his letter assenting to the 1894 marriage with Berthe de Rohan, an Austro-Hungarian subject. Melgar in his memoirs described the rule of Franz Joseph as "long and disastrous reign" which ruined the country, Melgar 1940, p. 95

- ↑ it is not entirely clear what the Austrians asked don Jaime for; according to one version they expected that he declares himself in favor of the Central Powers, according to another a declaration that he would merely refrain from anti-Central activity when in Austria, Andrés Martín 2000, p. 94

- ↑ e.g. he provoked his pro-Central enemies into demeaning comments about black French soldiers from Africa, Andrés Martín 1997, p. 107

- ↑ according to some scholars Melgar was not only pro-French but also pro-Russian, Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 485-6

- ↑ En desgravio, La mentira anónima, La gran víctima, Visita de un católico español a Inglaterra, La reconquista: a través del alma francesa

- ↑ Germany and Spain: The Views of a Spanish Catholic (London) - New Statesman, vol. 7, p. 428, available here, Amende honorable (1916 Paris, virulently dedicated "au grand Mella le petit Melgar", 80 pages, fully available here)

- ↑ Cristóbal Robles, Cristóbal Robles Muñoz, José María de Urquijo e Ybarra: opinión, religión y poder, Madrid 1997, ISBN 9788400076689, p. 376

- ↑ Andrés Martín 2000, p. 114

- ↑ Andrés Martín 2000, p. 127

- ↑ he was mentioned as appearing on a pro-French 1917 rally in Barcelona, ABC.24.03.17, available here

- ↑ Melgar presented don Jaime as a hypocrite, expecting to provoke Cerralbo into unguarded action; he might have edited messages from don Jaime so that they seemed pretty tolerant of clearly pro-German stand of El Correo Español, Andrés Martín 2000, p. 114; at the same time, he pronounced about "ilegal dictadura del Marqués de Cerralbo", Andrés Martín 2000, pp. 132-3

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 491, Andrés Martín 2000, p. 101

- ↑ Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXIX, Sevilla 1960, pp. 102-105, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 504

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 502

- ↑ Melchor Ferrer, Breve historia del legitimismo español, Madrid 1958, p. 102, José Luis Orella Martínez, El origen del primer catolicismo social español [PhD thesis at Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Madrid 2012. p. 181, Román Oyarzun, La historia del carlismo, Madrid 1965, p. 494

- ↑ Andrés Martín 2000, p. 147

- ↑ e.g. appointing Melchor Ferrer to director or El Correo Espanol, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 512

- ↑ though not entirely unused, e.g. Llorens declared that he was not a "melgarista", Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 521

- ↑ Ferrer 1960, pp. 115, 119-120, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 514

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, pp. 516-7, Andrés Martín 2000, p. 184, Ferrer 1960, pp. 124-130

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 473

- ↑ Mundo Gráfico 31.03.23

- ↑ when sacking him as a secretary, Carlos VII assigned him a generous pension equal to his salary, but the money ceased to arrive in Paris due to outbreak of the First World War, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 486

- ↑ La Lectura Dominical 13.03.26, available here

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 8

- ↑ see e.g. La Cruzada 27.02.69, available here or La Esperanza 09.02.72, available here

- ↑ La Esperanza 08.01.72, available here, also La Esperanza 06.09.69, available here

- ↑ quoted after José Manuel Vázquez-Romero, Tradicionales y moderados ante la difusión de la filosofía krausista en España, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788489708242, p. 95

- ↑ Melgar 1940, p. 9

- ↑ La Convicción 29.11.71, available here

- ↑ La Ilustración Católica 21.03.79, available here

- ↑ "y cuando Ramón fundó El Siglo Futuro, me llevó a mí como su primer redactor (…) terminada la guerra fui su corresponsal en París", Melgar 1940, p. 148

- ↑ Artagan 1912, p. 58; detailed discussion of the periodical in Horacio M. Sánchez de Loria Parodi, El Carlismo visto por el movimiento católico del ochenta, [in:] Fuego y Raya 7 (2014), pp. 42-44

- ↑ Región 06.03.26

- ↑ El Siglo Futuro 06.06.89, available here

- ↑ Canal 1998, p. 77

- ↑ B. de Artagan [Romualdo Brea], Principe heróico y soldados leales, Barcelona 1912, p. 120

- ↑ Arias Durá 2014, p. 40

- ↑ La Nación 05.03.26, available here

- ↑ also Visita de un católico español a Inglaterra, La reconquista: a través del alma francesa, Germany and Spain: The Views of a Spanish Catholic

- ↑ Región 06.03.26

- ↑ the British paper thought it amazing because "the Carlists are violently pro-German"; the pamphlet was published in massive circulation of 200,000, - New Statesman, vol. 7, p. 428, available here

- ↑ Hans A. Schmitt, Neutral Europe Between War and Revolution, 1917-23, Charlottesville 1988, ISBN 9780813911533, p. 54

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 26

- ↑ Real Cuesta 1985, p. 88, Ferrer 1959, p. 44

- ↑ Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 61

- ↑ compare here

- ↑ he is very often listed – usually in footnotes as a source rather than as a protagonist – in works dealing with the Carlist history of late 19th and early 20th century, e.g. in the work on Basque Carlism over 20 times, see Real Cuesta 1985, in the work on Catalan Carlism around 50 times, see Canal 1998, in the work on the Mellist breakup around 150 times, see Andrés Martín 2000, and in the work on marqués de Cerralbo over 600 times, see Fernández Escudero 2012

Further reading

- Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista: historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8487863825

- Jordi Canal i Morell, El carlisme català dins l’Espanya de la Restauració: un assaig de modernització politica (1888–1900), Barcelona 1998, ISBN 9788476022436

- Jordi Canal i Morell, Incómoda presencia: el exilio de don Carlos en París, [in:] Fernando Martínez López, Jordi Canal i Morell, Encarnación Lemus López (eds.), París, ciudad de acogida: el exilio español durante los siglos XIX y XX, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788492820122, pp. 85–112

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922): biografía politica [PhD thesis], Madrid 2012

- Carlos Mata Induráin, Siete cartas del conde de Melgar a Navarro Villoslada (1885-1886), [in:] Príncipe de Viana 213 (1998), pp. 307–324

- Francisco Melgar, Veinte años con Don Carlos. Memorias de su secretario, Madrid 1940

External links

- Melgar at biografiasvidas service

- Amende honorable at Gallica service

- Melgar's obituary at La Region

- Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda, Melgar at 2:41 (right, sitting) on YouTube