Fort Tryon Park

|

Fort Tryon Park and the Cloisters | |

|

(2013) | |

| |

| Location |

from Cabrini Circle, at the intersection of Carbini Blvd. and Fort Washington Avenue in the south, to Riverside Drive in the north, and from Broadway in the east to the Henry Hudson Parkway in the west Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°51′39″N 73°55′57″W / 40.86083°N 73.93250°WCoordinates: 40°51′39″N 73°55′57″W / 40.86083°N 73.93250°W |

| Area | 66.5 acres (26.9 ha) |

| Built | 1935 |

| Architect |

Olmsted Brothers:[1] (Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., James W. Dawson) |

| Architectural style | Romanesque |

| NRHP Reference # | 78001870[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 19, 1978 |

| Designated NYCL |

The Cloisters: March 19, 1974[3] Fort Tryon Park: September 20, 1983[4] |

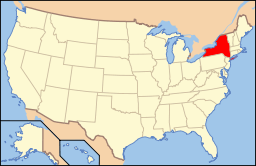

Fort Tryon Park is a public park located in the Hudson Heights and Inwood neighborhoods of the borough of Manhattan in New York City. The 67 acres (27 ha) park is situated on a ridge in Upper Manhattan, with a commanding view of the Hudson River, the George Washington Bridge, the New Jersey Palisades, Washington Heights, Inwood, The Bronx and the Harlem River.[5] It extends from Margaret Corbin Circle in the south to Riverside Drive at Dyckman Street in the north, and from Broadway in the east to the Henry Hudson Parkway in the west. The main entrance to the park is at Margaret Corbin Circle, at the intersection of Fort Washington Avenue and Cabrini Boulevard.

The area was known by the name Chquaesgeck by the local Lenape tribe, and was called Lange Bergh (Long Hill) by Dutch settlers until late in the 17th century.[5] It was the location where the Battle of Fort Washington was fought in the American Revolutionary War, but it was, and remained, sparsely populated. By the turn of the 20th century, it was the location of large country estates.

The park was the creation of philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who bought up several of the estates beginning in 1917 in order to create it. He engaged the Olmsted Brothers firm – formed by the sons of Frederick Law Olmsted, step-brothers John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. – to design the park, and gave it to the city in 1931;[5] James W. Dawson created the planting plan.[1][6] The park was completed in 1935.[5]

Rockefeller also bought sculptor George Gray Barnard's collection of medieval art and gave to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which from 1934 to 1939 built The Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park to house it.[1] The Cloisters, which was designed by Charles Collens, incorporates several medieval buildings that were purchased in Europe, brought to the United States, and reassembled, often stone by stone. It is home to the Unicorn Tapestries.

The park is built on a formation of Manhattan schist and contains interesting examples of igneous intrusions and of glacial striations from the last Ice Age. The lower lying regions to the east and north of the park are built on Inwood marble. The northern boundary of the park is formed by the Dyckman Street Fault.[7]

Fort Tryon Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 and was designated a New York City Scenic Landmark in 1983.

History

The park was an ancillary site of the American Revolutionary War Battle of Fort Washington, fought on November 16, 1776, between 2,900 American soldiers and 8,000 invading Hessian troops hired by Great Britain.[8] Margaret Corbin became the first woman to fight in the war and was wounded during the battle. Subsequently, the southern entrance to the park bears her name. The actual site of Fort Washington is less than a mile south at Bennett Park.[9] After the British victory, the outpost was named after Sir William Tryon, the last British Governor of the Province of New York.

As New York City expanded and prospered, the area was part of a country estate whose wealthy owners, included Dr. Samuel Watkins, founder of Watkins Glen, General Daniel Butterfield, Boss Tweed and C.K.G. Billings. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. purchased the Billings estate in 1917 – for $35,000 an acre[10] – as well as the contiguous Hays and Shaefer tracts to the north. He hired the Olmsted Brothers firm – and in particular Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., son of the designer of Central Park – to plan a park that he would give to the city. Olmsted's design capitalized on the topography to reveal sweeping vistas of the Hudson River and the Palisades. To preserve the views from Fort Tryon Park, Rockefeller purchased land on the opposite side of the Hudson to keep it from being developed, which later became park of Palisades Interstate Park. Olmsted Jr. was guided by the four principles of park design which his father had established in creating Central Park: the beautiful, as in small open lawns; the pcturesque, as seen in wooded slopes; the sublime, represented in the vistas of the Hudson River; and the gardenesque, exemplified by the park's Heather and Alpine Gardens.[7]

Fort Tryon Park was constructed during the Great Depression, providing many jobs. The project included the 190th Street subway station on the IND Eighth Avenue Line (today's A train), which is the closest New York City Subway station to the park's main (southern) entrance; the Dyckman Street station on the same line is closest to the northern end. The park was completed in 1935 providing open green space to Upper Manhattan. The park's design included extensive plantings of various flora in the park's many gardens, including a Heather Garden, which was restored in the 1980s; the park's plantings were designed by James W. Dawson.[6] Besides the gardens and the Cloisters, the park has extensive walking paths and meadows, with views of the Hudson and Harlem Rivers.

Remnants of the C.K.G. Billings estate are the Fort Tryon Cottage – located near the main entrance at Margaret Corbin Circle, at the intersection of Cabrini Boulevard and Fort Washington Avenue – which was originally a gatehouse, and the partially paved-over red-brick pathways near the entrance and continuing down through the massively arched structure known as the Billings Arcade. This was originally a driveway, which continues down to Riverside Drive, which is now the northbound side of the Henry Hudson Parkway.[11] The Billings Arcade features a series of 50-foot tall arches constructed of Maine granite.[10]

During the years before World War I, the park lent its name to the neighborhood to its south. The area between Broadway and the Hudson River, as far south as West 179th Street, was known as Fort Tryon. By the 1940s the neighborhood was known as Frankfurt-on-the-Hudson,[12] which gave way, in the 1990s, to Hudson Heights.[13]

The park's concessions building, which had fallen into disrepair, was restored beginning in 1995 by Bette Midler's New York Restoration Project (NYRP). The non-profit organization was awarded the operation of the concession in 2000, and opened the New Leaf Café – later called the New Leaf Restaurant and Bar – the next year.[14] The Parks Department closed the building for necessary roof repairs in December 2014, and NYRP announced that it would not reopen, due to the length of time the repairs would take and the increased rent it would be charged.[15] The operation of the restaurant was taken over in late April 2015 by Coffeed, a Queens-based which donates a portion of its revenue to local charities.[16]

On June 15, 2010 the park celebrated its 75th anniversary with a fundraiser and fireworks display.[17]

The Cloisters

The Cloisters is a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art which houses the museum's extensive collection of medieval European art and artifacts, including the noted Unicorn Tapestries. The museum's buildings are a combination of medieval structures bought in Europe and reconstructed on-site stone-by-stone, and new buildings in the medieval style designed by Charles Collens. The museum owes its existence to philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who purchased the medieval art collection of George Grey Barnard, and gave it to the Met along with his own collection. The Met then had the Cloisters built in Rockefeller's newly created Fort Tryon Park with endowment money from Rockefeller.

Together, the park and the Cloisters are listed as an historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. The Cloisters had been designated a New York City landmark in 1974, with Fort Tryon Park designed a scenic landmark in 1983.[1]

Fort Tryon Park Trust

The Fort Tryon Park Trust is a non-profit organization the mission of which is to promote the restoration, preservation, and enhancement of the park for the benefit and use of the surrounding community and all New Yorkers, through advocacy and fundraising, working in partnership with the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation and other organizations.[18]

As the City of New York suffered severe budget constraints in the 1970s and funds for parks were decimated, Fort Tryon Park's gardens, woodlands, and playgrounds fell into disuse and disrepair. The Park’s decline continued until the 1980s when funds became available and restoration efforts began.[19]

In 1983, Fort Tryon Park was designated an official New York City scenic landmark, and a plan was developed the following year to fully renovate the park. The park’s Heather Garden was one of the first projects slated for a much needed renovation.[19] It is the largest public garden with unrestricted access in New York City.[19] Thanks to the partnership between the Parks Department, the Greenacre Foundation, and volunteers, a three–year restoration of the garden was undertaken, reopening long–lost views of the Hudson and the Palisades in 1988. Since 1998, the Fort Tryon Park Trust has been working to build upon the Parks Department and the Greenacre Foundation’s initial restoration work, raising an endowment of close to $3 million to help preserve capital improvements made to date and to continue the revitalization throughout the park’s entire 67 acres.[19]

The Trust helps fund programs for all ages like yoga and tai chi classes, live outdoor concerts and bird walks. The Trust also supports the display of local artist in the park courtesy of the New York City Parks Temporary Public Art Program.

In popular culture

- 1948 – In the film Portrait of Jennie, starring Joseph Cotten, Jennifer Jones and Ethel Barrymore, the Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park was used as the location for a convent school.[20]

- 1968 – Two scenes in Coogan's Bluff, starring Clint Eastwood, were filmed in Fort Tryon Park, including a shoot-out at the Cloisters and a motorcycle chase in the Heather Garden.[20]

- 2011 – Scenes from the film The Adjustment Bureau, starring Matt Damon and Emily Blunt, were filmed in Fort Tryon Park.[21]

Gallery

The Heather Garden, one of the park's premiere attractions

The Heather Garden, one of the park's premiere attractions The cottage, used for Park offices

The cottage, used for Park offices The Billings Arcade, with the retaining wall (left) above which is the Billings Lawn

The Billings Arcade, with the retaining wall (left) above which is the Billings Lawn Pillars at The Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park.

Pillars at The Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park.

Memorial dedicated to Margaret Corbin, a hero of the American Revolution

Memorial dedicated to Margaret Corbin, a hero of the American Revolution A walkway in the summer

A walkway in the summer A water fountain, designed by the Olmstead Brothers

A water fountain, designed by the Olmstead Brothers The park's Gazebo, as seen from a pathway below

The park's Gazebo, as seen from a pathway below

The built-in benches were part of the Olmstead's original design

The built-in benches were part of the Olmstead's original design For 13 years, the New Leaf restaurant was part of Bette Midler's non-profit New York Restoration Project; in Spring 2015 another vendor took over the concession

For 13 years, the New Leaf restaurant was part of Bette Midler's non-profit New York Restoration Project; in Spring 2015 another vendor took over the concession The base of the flagstaff at the place where Fort Tryon stood

The base of the flagstaff at the place where Fort Tryon stood The archway through which Margaret Corbin Drive connects to the north-bound Henry Hudson Parkway

The archway through which Margaret Corbin Drive connects to the north-bound Henry Hudson Parkway Linden Terrace offers unobstructed views of the Hudson River and the Palisades

Linden Terrace offers unobstructed views of the Hudson River and the Palisades The view from Linden Terrace to the west: a barge on the Hudson River and the Hudson Palisades beyond, with the Englewood Cliffs campus of Saint Peter's University on the top

The view from Linden Terrace to the west: a barge on the Hudson River and the Hudson Palisades beyond, with the Englewood Cliffs campus of Saint Peter's University on the top

See also

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan above 110th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in New York County, New York

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S. (text); Postal, Matthew A. (text) (2009), Postal, Matthew A., ed., Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1, p.213

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "The Cloisters Designation Report"

- ↑ "Fort Tryon Park Designation Report"

- 1 2 3 4 Kuhn, Jonathan. "Fort Tryon Park" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010), The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.), New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2, p.473

- 1 2 White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010), AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.), New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195383867, p.573

- 1 2 Eldredge, Niles & Horenstein, Sidney (2014). Concrete Jungle: New York City and Our Last Best Hope for a Sustainable Future. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-520-27015-2.

- ↑ Washington Heights & Inwood Online: Battle of Fort Washington, accessed September 28, 2006

- ↑ New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. "Bennett Park." Accessed March 30, 2008

- 1 2 Renner, James (2007) Washington Heights, Inwood, and Marble Hill. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Arcadia Publishing. p.20 ISBN 0-7385-5478-2

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (December 22, 1996). "Monumental Remnant From a 1900's Estate". The New York Times. p. R5. Retrieved 2009-10-09. This article includes pictures of the Billings mansion and a contemporaneous photo of the arched structure.

- ↑ Lowenstein, Steven M. (1989) Frankfurt on the Hudson. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- ↑ Garb, Maggie (November 8, 1998). "If You're Thinking of Living In / Hudson Heights; High Above Hudson, a Crowd of Co-ops". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ↑ "New Leaf & Fort Tryon Park" on the New Leaf Restaurant website

- ↑ Armstrong, Linda (December 23, 2104) "Restaurant and Wedding Venue to Abruptly Close" DNAinfo

- ↑ Ranson, Jan (January 7, 2015) "Queens-based cafe to replace Fort Tryon Park restaurant and bar" New York Daily News

- ↑ Zanoi, Carla (June 16, 2010) "Fireworks Light Up the Northern Manhattan Sky for Fort Tryon Park's 75th Anniversary" DNAinfo.com Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Fort Tryon Park Trust". forttryonparktrust.org.

- 1 2 3 4 "Timeline" on the Fort Tryon Park Trust website

- 1 2 "The Cloisters in Popular Culture: "Time in This Place Does Not Obey an Order"". metmuseum.org.

- ↑ Zanoni, Carla (March 9, 2011). "Fort Tryon Park Stars in 'The Adjustment Bureau'". DNAinfo.com. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

Sources

- New York City Department of Parks and Recreation' "A Guide to Fort Tryon Park and the Heather Garden"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Tryon Park. |

- "Fort Tryon Park" on the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation website

- The Fort Tryon Park Trust

- Annual Medieval Festival in Fort Tryon Park

- Photos and identification of 800 flower varieties that bloom in Fort Tryon Park