Republic of Macedonia

| Republic of Macedonia | |

|---|---|

Location of Republic of Macedonia (green) in Europe (dark grey) – [Legend] | |

| Capital and largest city |

Skopje 42°0′N 21°26′E / 42.000°N 21.433°E |

| Official languages | Macedonian[1][2] |

| Recognized languages[3] | |

| Ethnic groups (2002) | |

| Demonym | Macedonian |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

| Gjorge Ivanov | |

| Zoran Zaev | |

| Legislature | Sobranie |

| Independence from SFR Yugoslavia | |

• Declared | 8 September 1991 |

| 8 April 1993 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 25,713 km2 (9,928 sq mi) (148th) |

• Water (%) | 1.9 |

| Population | |

| 2,073,702 | |

• 2002 census | 2,022,547[5] |

• Density | 80.1/km2 (207.5/sq mi) (122nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $30.377 billion[7] |

• Per capita | $14,631[7] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $10.424 billion[7] |

• Per capita | $5,021[7] |

| Gini (2013) |

medium |

| HDI (2015) |

high · 82nd |

| Currency | Macedonian denar (MKD) |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| CEST (UTC+2) | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Drives on the | right |

| Calling code | +389 |

| Patron saint | Saint Clement of Ohrid[10] |

| ISO 3166 code | MK |

| Internet TLD | |

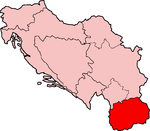

Macedonia (/ˌmæsɪˈdoʊniə/ mas-i-DOH-nee-ə; Macedonian: Македонија, tr. Makedonija, IPA: [makɛˈdɔnija]), officially the Republic of Macedonia (Macedonian: ![]() Република Македонија , tr. Republika Makedonija), is a country in the Balkan peninsula in Southeast Europe. It is one of the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, from which it declared independence in 1991. It became a member of the United Nations in 1993, but, as a result of an ongoing dispute with Greece over the use of the name "Macedonia", was admitted under the provisional description the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia[11][12] (sometimes abbreviated as FYROM and FYR Macedonia), a term that is also used by international organizations such as the European Union,[13] the Council of Europe[14] and NATO.[15]

Република Македонија , tr. Republika Makedonija), is a country in the Balkan peninsula in Southeast Europe. It is one of the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, from which it declared independence in 1991. It became a member of the United Nations in 1993, but, as a result of an ongoing dispute with Greece over the use of the name "Macedonia", was admitted under the provisional description the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia[11][12] (sometimes abbreviated as FYROM and FYR Macedonia), a term that is also used by international organizations such as the European Union,[13] the Council of Europe[14] and NATO.[15]

A landlocked country, the Republic of Macedonia has borders with Kosovo[a] to the northwest, Serbia to the north, Bulgaria to the east, Greece to the south, and Albania to the west.[16] It constitutes approximately the northwestern third of the larger geographical region of Macedonia, which also comprises the neighbouring parts of northern Greece and smaller portions of southwestern Bulgaria and southeastern Albania. The country's geography is defined primarily by mountains, valleys, and rivers. The capital and largest city, Skopje, is home to roughly a quarter of the nation's 2.06 million inhabitants. The majority of the residents are ethnic Macedonians, a South Slavic people. Albanians form a significant minority at around 25 percent, followed by Turks, Romani, Serbs, and others.

Macedonia's history dates back to antiquity, beginning with the kingdom of Paeonia, probably a mixed Thraco-Illyrian polity.[17] In the late sixth century BCE the area was incorporated into the Persian Achaemenid Empire, then annexed by the Kingdom of Macedonia in the fourth century BCE. The Romans conquered the region in the second century BCE and made it part of the much larger province of Macedonia. Macedonia remained part of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire, and was often raided and settled by Slavic peoples beginning in the sixth century CE. Following centuries of contention between the Bulgarian and Byzantine empires, it gradually came under Ottoman dominion from the 14th century. Between the late 19th and early 20th century, a distinct Macedonian identity emerged, although following the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, the modern territory of Macedonia came under Serbian rule. In the aftermath of the First World War (1914–1918) it became incorporated into the Serb-dominated Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which after the Second World War was re-established as a republic (1945) and which became the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963. Macedonia remained a constituent socialist republic within Yugoslavia until its peaceful secession in 1991.

Macedonia is a member of the UN and of the Council of Europe. Since 2005 it has also been a candidate for joining the European Union and has applied for NATO membership. Although one of the poorest countries in Europe, Macedonia has made significant progress in developing an open, market-based economy.

Etymology

The country's name derives from the Greek Μακεδονία (Makedonía),[18][19] a kingdom (later, region) named after the ancient Macedonians. Their name, Μακεδόνες (Makedónes), derives ultimately from the ancient Greek adjective μακεδνός (makednós), meaning "tall, taper",[20] which shares the same root as the adjective μακρός (makrós), meaning "long, tall, high" in ancient Greek.[21] The name is originally believed to have meant either "highlanders" or "the tall ones", possibly descriptive of the people.[19][22][23] However, Robert S. P. Beekes supports that both terms are of Pre-Greek substrate origin and cannot be explained in terms of Indo-European morphology.[24]

History

Ancient and Roman period

The Republic of Macedonia roughly corresponds to the ancient kingdom of Paeonia,[25][26][27][28] which was located immediately north of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia.[29] Paeonia was inhabited by the Paeonians, a Thracian people,[30] whilst the northwest was inhabited by the Dardani and the southwest by tribes known historically as the Enchelae, Pelagones and Lyncestae; the latter two are generally regarded as Molossian tribes of the northwestern Greek group, whilst the former two are considered Illyrian.[31][32][33][34][35][36]

In the late 6th century BC, the Achaemenid Persians under Darius the Great conquered the Paeonians, incorporating what is today the Republic of Macedonia within their vast territories.[37][38][39] Following the loss in the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 479 BC, the Persians eventually withdrew from their European territories, including from what is today the Republic of Macedonia.

In 356 BC Philip II of Macedon absorbed[40] the regions of Upper Macedonia (Lynkestis and Pelagonia) and the southern part of Paeonia (Deuriopus) into the kingdom of Macedon.[41] Philip's son Alexander the Great conquered the remainder of the region, and incorporated it in his empire, reaching as far north as Scupi, but the city and the surrounding area remained part of Dardania.[42]

The Romans established the Province of Macedonia in 146 BC. By the time of Diocletian, the province had been subdivided between Macedonia Prima ("first Macedonia") on the south, encompassing most of the kingdom of Macedon, and Macedonia Salutaris (known also as Macedonia Secunda, "second Macedonia") on the north, encompassing partially Dardania and the whole of Paeonia; most of the country's modern boundaries fell within the latter, with the city of Stobi as its capital.[43] Roman expansion brought the Scupi area under Roman rule in the time of Domitian (81–96 AD), and it fell within the Province of Moesia.[44] Whilst Greek remained the dominant language in the eastern part of the Roman empire, Latin spread to some extent in Macedonia.[45]

Medieval and Ottoman period

Slavic peoples settled in the Balkan region including Macedonia by the late 6th century AD. During the 580s, Byzantine literature attests to the Slavs raiding Byzantine territories in the region of Macedonia, later aided by Bulgars. Historical records document that in c. 680 a group of Bulgars, Slavs and Byzantines led by a Bulgar called Kuber settled in the region of the Keramisian plain, centred on the city of Bitola.[46] Presian's reign apparently coincides with the extension of Bulgarian control over the Slavic tribes in and around Macedonia. The Slavic peoples that settled in the region of Macedonia converted to Christianity around the 9th century during the reign of Tsar Boris I of Bulgaria.

In 1014, the Byzantine Emperor Basil II defeated the armies of Tsar Samuil of Bulgaria, and within four years the Byzantines restored control over the Balkans (including Macedonia) for the first time since the 7th century. However, by the late 12th century, Byzantine decline saw the region contested by various political entities, including a brief Norman occupation in the 1080s.

In the early 13th century, a revived Bulgarian Empire gained control of the region. Plagued by political difficulties, the empire did not last, and the region came once again under Byzantine control in the early 14th century. In the 14th century, it became part of the Serbian Empire, who saw themselves as liberators of their Slavic kin from Byzantine despotism. Skopje became the capital of Tsar Stefan Dusan's empire.

Following Dusan's death, a weak successor appeared, and power struggles between nobles divided the Balkans once again. These events coincided with the entry of the Ottoman Turks into Europe. The Kingdom of Prilep was one of the short-lived states that emerged from the collapse of the Serbian Empire in the 14th century.[47] Gradually, all of the central Balkans were conquered by the Ottoman Empire and remained under its domination for five centuries.

Macedonian nationalism

With the beginning of the Bulgarian National Revival in the 18th century, many of the reformers were from this region, including the Miladinov Brothers,[48] Rajko Žinzifov, Joakim Krčovski,[49] Kiril Pejčinoviḱ[50] and others. The bishoprics of Skopje, Debar, Bitola, Ohrid, Veles and Strumica voted to join the Bulgarian Exarchate after it was established in 1870.[51]

Several movements whose goals were the establishment of an autonomous Macedonia, which would encompass the entire region of Macedonia, began to arise in the late 19th century; the earliest of these was the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, later becoming Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (SMARO). In 1905 it was renamed the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO), and after World War I the organisation separated into the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) and the Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organisation (ITRO).[52]

In the early years of the organisation, membership was open to only Bulgarians, but later it was opened to all inhabitants of European Turkey, regardless of their nationality or religion.[53] The majority of its members, however, were Macedonian Bulgarians.[54] In 1903, IMRO organised the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising against the Ottomans, which after some initial successes, including the forming of the "Kruševo Republic", was crushed with much loss of life.[55] The uprising and the forming of the Kruševo Republic are considered the cornerstone and precursors to the eventual establishment of the Macedonian state.[56][57][58]

Kingdoms of Serbia and Yugoslavia

Following the two Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913 and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, most of its European-held territories were divided between Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia.[59] The territory of the modern Macedonian state was annexed by Serbia and named Južna Srbija, "Southern Serbia". Following the partition, an anti-Bulgarian campaign was carried out in the areas under Serbian and Greek control.[60] As many as 641 Bulgarian schools and 761 churches were closed by the Serbs, while Exarchist clergy and teachers were expelled.[60] The use of Bulgarian (including all Macedonian dialects) was proscribed.[60]

In the fall of 1915, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers in the First World War and gained control over most of the territory of the present-day Republic of Macedonia.[60] After the end of the First World War, the area returned to Serbian control as part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes[61] and saw a reintroduction of the anti-Bulgarian measures of the first occupation (1913–1915): Bulgarian teachers and clergy were expelled, Bulgarian language signs and books removed, and all Bulgarian organisations dissolved.[60]

The Serbian government pursued a policy of forced Serbianisation in the region,[62][63] which included systematic repression of Bulgarian activists, altering family surnames, internal colonisation, forced labor, and intense propaganda.[64] To aid the implementation of this policy, some 50,000 Serbian army and gendermerie were stationed in Macedonia.[60] By 1940 about 280 Serbian colonies (comprising 4,200 families) were established as part of the government's internal colonisation program (initial plans envisaged 50,000 families settling in Macedonia).[60]

In 1929, the Kingdom was officially renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and divided into provinces called banovinas. Southern Serbia, including all of what is now the Republic of Macedonia, became known as the Vardar Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.[65]

The concept of a United Macedonia was used by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) in the interbellum. Its leaders – including Todor Alexandrov, Aleksandar Protogerov, and Ivan Mihailov – promoted independence of the Macedonian territory split between Serbia and Greece for the whole population, regardless of religion and ethnicity.[66] The Bulgarian government of Alexander Malinov in 1918 offered to give Pirin Macedonia for that purpose after World War I,[67] but the Great Powers did not adopt this idea because Serbia and Greece opposed it. In 1924, the Communist International suggested that all Balkan communist parties adopt a platform of a "united Macedonia" but the suggestion was rejected by the Bulgarian and Greek communists.[68]

IMRO followed by starting an insurgent war in Vardar Banovina, together with Macedonian Youth Secret Revolutionary Organization, which also conducted guerilla attacks against the Serbian administrative and army officials there. In 1923 in Stip, a paramilitary organisation called Association against Bulgarian Bandits was formed by Serbian chetniks, IMRO renegades and Macedonian Federative Organization (MFO) members to oppose IMRO and MMTRO.[69]

The Macedonist ideas increased during the interbellum, in Yugoslav Vardar Macedonia, and among the left diaspora in Bulgaria, and were supported by the Comintern.[70] In 1934, it issued a special resolution in which for the first time directions were provided for recognizing the existence of a separate Macedonian nation and Macedonian language.[71]

World War II period

During World War II, Yugoslavia was occupied by the Axis Powers from 1941 to 1945. The Vardar Banovina was divided between Bulgaria and Italian-occupied Albania. Bulgarian Action Committees were established to prepare the region for the new Bulgarian administration and army.[72] The Committees were mostly formed by former members of IMRO, but some communists such as Panko Brashnarov, Strahil Gigov and Metodi Shatorov also participated.[73][74]

As leader of the Vardar Macedonia communists, Shatorov switched from the Yugoslav Communist Party to the Bulgarian Communist Party[74][75] and refused to start military action against the Bulgarian army.[76] The Bulgarian authorities, under German pressure,[77] were responsible for the round-up and deportation of over 7,000 Jews in Skopje and Bitola.[78] Harsh rule by the occupying forces encouraged many Macedonians to support the Communist Partisan resistance movement of Josip Broz Tito after 1943,[79] and the National Liberation War ensued, with German forces being driven out of Macedonia by the end of 1944.[80][81]

In Vardar Macedonia, after the Bulgarian coup d'état of 1944, the Bulgarian troops, surrounded by German forces, fought their way back to the old borders of Bulgaria.[82] Under the leadership of the new Bulgarian pro-Soviet government, four armies, 455,000 strong in total, were mobilised and reorganised. Most of them re-entered occupied Yugoslavia in early October 1944 and moved from Sofia to Niš, Skopje and Pristina with the strategic task of blocking the German forces withdrawing from Greece.[83] Compelled by the Soviet Union with a view towards the creation of a large South Slav Federation, the Bulgarian government once again offered to give Pirin Macedonia to such a United Macedonia in 1945.

Socialist Yugoslavia period

In 1944 the Anti-Fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) proclaimed the People's Republic of Macedonia as part of the People's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[84] ASNOM remained an acting government until the end of the war. The Macedonian alphabet was codified by linguists of ASNOM, who based their alphabet on the phonetic alphabet of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and the principles of Krste Petkov Misirkov.

The new republic became one of the six republics of the Yugoslav federation. Following the federation's renaming as the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963, the People's Republic of Macedonia was likewise renamed, becoming the Socialist Republic of Macedonia.[85][86][87] During the civil war in Greece (1946–1949), Macedonian communist insurgents supported the Greek communists. Many refugees fled to the Socialist Republic of Macedonia from there. The state dropped the "Socialist" from its name in 1991 when it peacefully seceded from Yugoslavia.

Declaration of independence

The country officially celebrates 8 September 1991 as Independence day (Macedonian: Ден на независноста, Den na nezavisnosta), with regard to the referendum endorsing independence from Yugoslavia, albeit legalising participation in future union of the former states of Yugoslavia.[88] The anniversary of the start of the Ilinden Uprising (St. Elijah's Day) on 2 August is also widely celebrated on an official level as the Day of the Republic.

Robert Badinter, as the head of the Arbitration Commission of the Peace Conference on Yugoslavia, recommended EC recognition in January 1992.[89]

Macedonia remained at peace through the Yugoslav wars of the early 1990s. A few very minor changes to its border with Yugoslavia were agreed upon to resolve problems with the demarcation line between the two countries. However, it was seriously destabilised by the Kosovo War in 1999, when an estimated 360,000 ethnic Albanian refugees from Kosovo took refuge in the country.[90] Although they departed shortly after the war, Albanian nationalists on both sides of the border took up arms soon after in pursuit of autonomy or independence for the Albanian-populated areas of Macedonia.[90][91]

Albanian insurgency

A conflict took place between the government and ethnic Albanian insurgents, mostly in the north and west of the country, between February and August 2001.[91][92][93][94] The war ended with the intervention of a NATO ceasefire monitoring force. Under the terms of the Ohrid Agreement, the government agreed to devolve greater political power and cultural recognition to the Albanian minority.[95] The Albanian side agreed to abandon separatist demands and to recognise all Macedonian institutions fully. In addition, according to this accord, the NLA were to disarm and hand over their weapons to a NATO force.[96]

Geography

Macedonia has a total area of 25,713 km2 (9,928 sq mi). It lies between latitudes 40° and 43° N, and mostly between longitudes 20° and 23° E (a small area lies east of 23°). Macedonia has some 748 km (465 mi) of boundaries, shared with Serbia (62 km or 39 mi) to the North, Kosovo (159 km or 99 mi) to the northwest, Bulgaria (148 km or 92 mi) to the east, Greece (228 km or 142 mi) to the south, and Albania (151 km or 94 mi) to the west. It is a transit way for shipment of goods from Greece, through the Balkans, towards Eastern, Western and Central Europe and through Bulgaria to the east. It is part of a larger region also known as Macedonia, which also includes Macedonia (Greece) and the Blagoevgrad province in southwestern Bulgaria.

Topography

Macedonia is a landlocked country that is geographically clearly defined by a central valley formed by the Vardar river and framed along its borders by mountain ranges. The terrain is mostly rugged, located between the Šar Mountains and Osogovo, which frame the valley of the Vardar river. Three large lakes — Lake Ohrid, Lake Prespa and Dojran Lake — lie on the southern borders, bisected by the frontiers with Albania and Greece. Ohrid is considered to be one of the oldest lakes and biotopes in the world.[97] The region is seismically active and has been the site of destructive earthquakes in the past, most recently in 1963 when Skopje was heavily damaged by a major earthquake, killing over 1,000.

Macedonia also has scenic mountains. They belong to two different mountain ranges: the first is the Šar Mountains[98][99] that continues to the West Vardar/Pelagonia group of mountains (Baba Mountain, Nidže, Kozuf and Jakupica), also known as the Dinaric range. The second range is the Osogovo–Belasica mountain chain, also known as the Rhodope range. The mountains belonging to the Šar Mountains and the West Vardar/Pelagonia range are younger and higher than the older mountains of the Osogovo-Belasica mountain group. Mount Korab of the Šar Mountains on the Albanian border, at 2,764 m (9,068 ft), is the tallest mountain in Macedonia.

Hydrography

In the Republic of Macedonia there are 1,100 large sources of water. The rivers flow into three different basins: the Aegean, the Adriatic and the Black Sea.[100]

The Aegean basin is the largest. It covers 87% of the territory of the Republic, which is 22,075 square kilometres (8,523 sq mi). Vardar, the largest river in this basin, drains 80% of the territory or 20,459 square kilometres (7,899 sq mi). Its valley plays an important part in the economy and the communication system of the country. The project named 'The Vardar Valley' is considered to be crucial for the strategic development of the country.

The river Black Drin forms the Adriatic basin, which covers an area of about 3,320 km2 (1,282 sq mi), i.e., 13% of the territory. It receives water from Lakes Prespa and Ohrid.

The Black Sea basin is the smallest with only 37 km2 (14 sq mi). It covers the northern side of Mount Skopska Crna Gora. This is the source of the river Binachka Morava, which joins the Morava, and later, the Danube, which flows into the Black Sea.

Macedonia has around fifty ponds and three natural lakes, Lake Ohrid, Lake Prespa and Lake Dojran.

In Macedonia there are nine spa towns and resorts: Banište, Banja Bansko, Istibanja, Katlanovo, Kežovica, Kosovrasti, Banja Kočani, Kumanovski Banji and Negorci.

Climate

Macedonia has a transitional climate from Mediterranean to continental. The summers are hot and dry, and the winters are moderately cold. Average annual precipitation varies from 1,700 mm (66.9 in) in the western mountainous area to 500 mm (19.7 in) in the eastern area. There are three main climatic zones in the country: temperate Mediterranean, mountainous, and mildly continental. Along the valleys of the Vardar and Strumica rivers, in the regions of Gevgelija, Valandovo, Dojran, Strumica, and Radoviš, the climate is temperate Mediterranean. The warmest regions are Demir Kapija and Gevgelija, where the temperature in July and August frequently exceeds 40 °C (104 °F). The mountainous climate is present in the mountainous regions of the country, and it is characterised by long and snowy winters and short and cold summers. The spring is colder than the fall. The majority of Macedonia has a moderate continental climate with warm and dry summers and relatively cold and wet winters. There are thirty main and regular weather stations in the country.

National parks

The country has three national parks:

| Name | Established | Size | Map | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mavrovo | 1948 | 731 km² |

|

|

| Galičica | 1958 | 227 km² |

|

|

| Pelister | 1948 | 125 km² |

|

|

Flora

The flora of Republic of Macedonia is represented by around 210 families, 920 genera, and around 3,700 plant species. The most abundant group are the flowering plants with around 3,200 species, followed by mosses (350 species) and ferns (42).

Phytogeographically, Macedonia belongs to the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Digital Map of European Ecological Regions by the European Environment Agency, the territory of the Republic can be subdivided into four ecoregions: the Pindus Mountains mixed forests, Balkan mixed forests, Rhodopes mixed forests and Aegean sclerophyllous and mixed forests.

National Park of Pelister in Bitola is known for the presence of the endemic Macedonian Pine, as well as some 88 species of plants representing almost 30 percent of Macedonian dendroflora. The Macedonian Pine forests on Pelister are divided into two communities: pine forests with ferns and pine forests with junipers. The Macedonian Pine, as a specific conifer species, is a relict of tertiary flora, and the five-needle pine Molika, was first noted on Pelister in 1893.

Macedonia's limited forest growth also includes Macedonian Oaks, the sycamore, weeping willows, white willows, alders, poplars, elms, and the common ash. Near the rich pastures on Šar Mountain and Bistra, Mavrovo, is another plant species characteristic of plant life in Macedonia—the poppy. The quality of thick poppy juice is measured worldwide by morphine units; while Chinese opium contains eight such units and is considered to be of high quality, Indian opium contains seven units, and Turkish opium only six, Macedonian opium contains a full 14 morphine units and is one of the best quality opiums in the world.[101]

Fauna

The fauna of Macedonian forests is abundant and includes bears, wild boars, wolves, foxes, squirrels, chamois and deer. The lynx is found, although very rarely, in the mountains of western Macedonia, while deer can be found in the region of Demir Kapija. Forest birds include the blackcap, the grouse, the black grouse, the imperial eagle and the forest owl.

The three artificial lakes of the country represent a separate fauna zone, an indication of long-lasting territorial and temporal isolation. The fauna of Lake Ohrid is a relict of an earlier era and the lake is widely known for its letnica trout, lake whitefish, gudgeon, roach, podust, and pior, as well as for certain species of snails of a genus older than 30 million years; similar species can be found only in Lake Baikal. Lake Ohrid is also noted in zoology texts for the European eel and its baffling reproductive cycle: it comes to Lake Ohrid from the distant Sargasso Sea,[102][103] thousands of kilometres away, and lurks in the depths of the lake for 10 years. When sexually mature, the eel is driven by unexplained instincts in the autumn to set off back to its point of birth. There it spawns and dies, leaving its offspring to seek out Lake Ohrid to begin the cycle anew.[103]

Domestic animals

The shepherd dog of Šar Mountain is known worldwide as Šarplaninec (Yugoslav shepherd).[104][105][106] It stands some 60 centimetres (2.0 ft) tall[104] and is a brave and fierce fighter that may be called upon to fight bears or wolf packs while guarding and defending flocks. The Šarplaninec originates from the shepherd's dog of the ancient Epirotes, the molossus, but the Šarplaninec was recognised as its own breed in 1939 under the name of "Illyrian shepherd" and since 1956 has been known as Šarplaninec.[104][105][106]

Politics

Macedonia is a parliamentary democracy with an executive government composed of a coalition of parties from the unicameral legislature (Собрание, Sobranie) and an independent judicial branch with a constitutional court. The Assembly is made up of 120 seats and the members are elected every four years. The role of the President of the Republic is mostly ceremonial, with the real power resting in the hands of the President of the Government. The President is the commander-in-chief of the state armed forces and a president of the state Security Council. The President is elected every five years and he or she can be elected twice at most. On the second run of the presidential elections held on 5 April 2009, Gjorge Ivanov was elected as new Macedonian president.[107]

With the passage of a new law and elections held in 2005, local government functions are divided between 78 municipalities (општини, opštini; singular: општина, opština). The capital, Skopje, is governed as a group of ten municipalities collectively referred to as the "City of Skopje". Municipalities in Macedonia are units of local self-government. Neighbouring municipalities may establish co-operative arrangements.

The country's main political divergence is between the largely ethnically based political parties representing the country's ethnic Macedonian majority and Albanian minority. The issue of the power balance between the two communities led to a brief war in 2001, following which a power-sharing agreement was reached. In August 2004, Macedonia's parliament passed legislation redrawing local boundaries and giving greater local autonomy to ethnic Albanians in areas where they predominate.

After a troublesome pre-election campaign, Macedonia saw a relatively calm and democratic change of government in the elections held on 5 July 2006. The elections were marked by a decisive victory of the centre-right party VMRO-DPMNE led by Nikola Gruevski. Gruevski's decision to include the Democratic Party of Albanians in the new government, instead of the Democratic Union for Integration – Party for Democratic Prosperity coalition which won the majority of the Albanian votes, triggered protests throughout the parts of the country with a respective number of Albanian population. However, a dialogue was later established between the Democratic Union for Integration and the ruling VMRO-DMPNE party as an effort to talk about the disputes between the two parties and to support European and NATO aspirations of the country.[108]

After the early parliamentary elections held in 2008, VMRO-DPMNE and Democratic Union for Integration formed a ruling coalition in Macedonia.[109]

In April 2009, presidential and local elections in the country were carried out peacefully, which was crucial for Macedonian aspirations to join the EU.[110] The ruling conservative VMRO-DPMNE party won a victory in the local elections and the candidate supported by the party, Gjorgi Ivanov, was elected as the new president.

Governance

Parliament, or Sobranie (Macedonian: Собрание), is the country's legislative body. It makes, proposes and adopts laws. The Constitution of the Republic of Macedonia has been in use since the formation of the republic in the 1993. It limits the power of the government's, both local and national. The military is also limited by the constitution. The constitution states that Macedonia is a social free state, and that Skopje is the capital.[111] The 120 members are elected for a mandate of four years through a general election. Each citizen aged 18 years or older can vote for one of the political parties. The current president of Parliament is Trajko Veljanovski.

Executive power in Macedonia is exercised by the Government, whose prime minister is the most politically powerful person in the country. The members of the government are chosen by the Prime Minister and there are ministers for each branch of the society. There are ministers for economy, finance, information technology, society, internal affairs, foreign affairs and other areas. The members of the Government are elected for a mandate of four years. The current Prime Minister is Nikola Gruevski who is serving his third consecutive term in office.

Law and courts

Judiciary power is exercised by courts, with the court system being headed by the Judicial Supreme Court, Constitutional Court and the Republican Judicial Council. The assembly appoints the judges.

Foreign relations

Macedonia became a member state of the UN on 8 April 1993, eighteen months after its independence from Yugoslavia. It is referred to within the UN as "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", pending a resolution of the long-running dispute with Greece about the country's name.

The major interest of the country is a full integration in the European and the Trans-Atlantic integration processes. Five foreign policy priorities are:[112]

- Commencing negotiations for full-fledged membership in the European Union

- Lifting the visa regime for Macedonian nationals

- NATO membership

- Resolving the naming issue with Greece

- Strengthening the economic and public diplomacy

Macedonia is a member of the following international and regional organisations:[113] IMF (since 1992), WHO (since 1993), EBRD (since 1993), Central European Initiative (since 1993), Council of Europe (since 1995), OSCE (since 1995), SECI (since 1996), WTO (since 2003), CEFTA (since 2006), La Francophonie (since 2001).

In 2005, the country was officially recognised as a European Union candidate state.

On the NATO summit held in Bucharest in April 2008, Macedonia failed to gain an invitation to join the organisation because Greece vetoed the move after the dispute over the name issue.[114] The USA had previously expressed support for an invitation,[115] but the summit then decided to extend an invitation only on condition of a resolution of the naming conflict with Greece.

In March 2009, the European Parliament expressed support for Macedonia's EU candidacy and asked the EU Commission to grant the country a date for the start of accession talks by the end of 2009. The parliament also recommended a speedy lifting of the visa regime for Macedonian citizens.[116] However, Macedonia has so far failed to receive a start date for accession talks as a result of the naming dispute. The EU's stance is similar to NATO's in that resolution of the naming dispute is a precondition for the start of accession talks.

In October 2012, the EU Enlargement Commissioner Štefan Füle proposed a start of accession negotiations with Macedonia for the fourth time, while the previous efforts were blocked each time by Greece. At the same time Füle visited Bulgaria in a bid to clarify the state's position with respect to Macedonia. He established that Bulgaria almost has joined Greece in vetoing the accession talks with Macedonia. The Bulgarian position was that Sofia cannot grant an EU certificate to Skopje, which is systematically employing an ideology of hate towards Bulgaria.[117]

Naming dispute

After the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991, the name of Macedonia became the object of a dispute between Greece and the newly independent Republic of Macedonia.[118] In the south, the Republic of Macedonia borders the region of Greek Macedonia, which administratively is split into three peripheries (one of them comprising both Western Thrace and a part of Greek Macedonia). Citing historical and territorial concerns resulting from the ambiguity between the Republic of Macedonia, the adjacent Greek region of Macedonia and the ancient kingdom of Macedon which falls within Greek Macedonia, Greece opposes the use of the name "Macedonia" by the Republic of Macedonia without a geographical qualifier, supporting a compound name (such as "Northern Macedonia") for use by all and for all purposes (erga omnes).[119] As millions of ethnic Greeks identify themselves as Macedonians, unrelated to the Slavic people who are associated with the Republic of Macedonia, Greece further objects to the use of the term "Macedonian" for the neighboring country's largest ethnic group. The Republic of Macedonia is accused of appropriating symbols and figures that are historically considered parts of Greece's culture (such as Vergina Sun, a symbol associated with the ancient kingdom of Macedon, and Alexander the Great), and of promoting the irredentist concept of a United Macedonia, which would include territories of Greece, Bulgaria, Albania, and Serbia.

From 1992 to 1995, the two countries engaged in a dispute over the Macedonian state's new flag, which incorporated the Vergina Sun symbol. This aspect of the dispute was resolved when the flag was changed under the terms of an interim accord agreed between the two states in October 1995.

The UN adopted the provisional reference "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" (Macedonian: Поранешна Југословенска Република Македонија) when the country was admitted to the organisation in 1993.[120] Most international organisations, such as the European Union, the European Broadcasting Union, and the International Olympic Committee, adopted the same convention.[121][122][123][124][125] NATO also uses the reference in official documents but adds an explanation on which member countries recognise the constitutional name.[126] The same reference is also used in any discussion to which Greece is a party[127]

However, most UN member countries have abandoned the provisional reference and have recognised the country as the Republic of Macedonia instead. These include four of the five permanent UN Security Council members: the United States,[128] Russia, United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China; several members of the European Union such as Bulgaria, Poland, and Slovenia; and over 100 other UN members.[129] The UN has set up a negotiating process with a mediator, Matthew Nimetz, and the two parties to the dispute, Macedonia and Greece, to try to mediate the dispute. Negotiations continue between the two sides but have yet to reach any settlement of the dispute.

Initially the European Community-nominated Arbitration Commission's opinion was that "the use of the name 'Macedonia' cannot therefore imply any territorial claim against another State";[130] despite the commission's opinion, Greece continued to object to the establishment of relations between the Community and the Republic under its constitutional name.[131]

Since the coming to power in 2006, and especially since Macedonia's non-invitation to NATO in 2008, the VMRO-DPMNE government has pursued a policy of "Antiquisation" ("Antikvizatzija") as a way of putting pressure on Greece as well as for the purposes of domestic identity-building.[132] Statues of Alexander the Great and Philip of Macedon have been built in several cities across the country. Additionally, many pieces of public infrastructure, such as airports, highways, and stadiums have been renamed after Alexander and Philip. These actions are seen as deliberate provocations in neighboring Greece, exacerbating the dispute and further stalling Macedonia's EU and NATO applications.[133] The policy has also attracted criticism domestically, as well as from EU diplomats.[132]

In November 2008, Macedonia instituted proceedings before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against Greece alleging violations of the 1995 Interim Accord that blocked its accession to NATO.[134] The ICJ was requested to order Greece to observe its obligations within the Accord, which is legally binding for both countries. In 2011, The United Nations' International Court of Justice ruled that Greece violated Article 11 of the 1995 Interim Accord by vetoing Macedonia's bid for NATO membership at the 2008 summit in Bucharest.[135] The court, however, did not consider it necessary to grant Macedonia's request that it instruct Greece to refrain from similar actions in the future since "[a]s a general rule, there is no reason to suppose that a State whose act or conduct has been declared wrongful by the Court will repeat that act or conduct in the future, since its good faith must be presumed";[136] nor has there been to date a change in the EU's stance that Macedonia's accession negotiations cannot begin until the name issue is resolved.[137]

Administrative divisions

Macedonia's statistical regions exist solely for legal and statistical purposes. The regions are:

In August 2004, the Republic of Macedonia was reorganised into 84 municipalities (opštini; sing. opština); 10 of the municipalities constitute the City of Skopje, a distinct unit of local self-government and the country's capital.

Most of the current municipalities were unaltered or merely amalgamated from the previous 123 municipalities established in September 1996; others were consolidated and their borders changed. Prior to this, local government was organised into 34 administrative districts, communes, or counties (also opštini).

Human rights

The Republic of Macedonia is a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights and the U.N. Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and Convention against Torture, and the Constitution guarantees basic human rights to all Macedonian citizens.

There do, however, continue to be problems with human rights. According to human rights organisations, in 2003 there were suspected extrajudicial executions, threats against, and intimidation of, human rights activists and opposition journalists, and allegations of torture by the police.[138][139]

Military

The Macedonian Armed Forces comprise the army, air force and Special Forces. The government's national defence policy aims to guarantee the preservation of the independence and sovereignty of the state, the integrity of its land area and airspace and its constitutional order. Its main goals remain the development and maintenance of a credible capability to defend the nation's vital interests and development of the Armed Forces in a way that ensures their interoperability with the armed forces of NATO and the European Union member states and their capability to participate in the full range of NATO missions.

The Ministry of Defence develops the Republic's defence strategy and assesses possible threats and risks. It is also responsible for the defence system, including training, readiness, equipment, and development, and for drawing up and presenting the defence budget.[140]

Economy

Ranked as the fourth "best reformatory state" out of 178 countries ranked by the World Bank in 2009, Macedonia has undergone considerable economic reform since independence.[141] The country has developed an open economy with trade accounting for more than 90% of GDP in recent years. Since 1996, Macedonia has witnessed steady, though slow, economic growth with GDP growing by 3.1% in 2005. This figure was projected to rise to an average of 5.2% in the 2006–2010 period.[142] The government has proven successful in its efforts to combat inflation, with an inflation rate of only 3% in 2006 and 2% in 2007,[141] and has implemented policies focused on attracting foreign investment and promoting the development of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The current government introduced a flat tax system with the intention of making the country more attractive to foreign investment. The flat tax rate was 12% in 2007 and was further lowered to 10% in 2008.[143][144]

Despite these reforms, as of 2005 Macedonia's unemployment rate was 37.2%[145] and as of 2006 its poverty rate was 22%.[142] However, due to a number of employment measures as well as the successful process of attracting multinational corporations, and according to the Macedonian State Statistical Office, country's unemployment rate in the first quarter of 2015 decreased to 27.3%.[146] Government's policies and efforts in regards to foreign direct investments have resulted with the establishment of local subsidiaries of several world leading manufacturing companies, especially from the automotive industry, such as: Johnson Controls Inc., Van Hool NV, Johnson Matthey plc, Lear Corp., Visteon Corp., Kostal GmbH, Gentherm Inc., Dräxlmaier Group, Kromberg & Schubert, Marquardt GmbH, Amphenol Corp., Tekno Hose SpA, KEMET Corp., Key Safety Systems Inc., ODW-Elektrik GmbH, etc.

Macedonia has one of the highest shares of people struggling financially, with 72% of its citizens stating that they could manage on their household’s income only "with difficulty" or "with great difficulty", though Macedonia, along with Croatia, was the only country in the Western Balkans to not report an increase in this statistic.[147] Corruption and a relatively ineffective legal system also act as significant restraints on successful economic development. Macedonia still has one of the lowest per capita GDPs in Europe. Furthermore, the country's grey market is estimated at close to 20% of GDP.[148]

In terms of GDP structure, as of 2013 the manufacturing sector, including mining and construction constituted the largest part of GDP at 21.4%, up from 21.1% in 2012. The trade, transportation and accommodation sector represents 18.2% of GDP in 2013, up from 16.7% in 2012, while agriculture represents 9.6%, up from 9.1% in the previous year.[149]

In terms of foreign trade, the largest sector contributing to the country's export in 2014 was "chemicals and related products" at 21.4%, followed by the "machinery and transport equipment" sector at 21.1%. Macedonia's main import sectors in 2014 were "manufactured goods classified chiefly by material" with 34.2%, "machinery and transport equipment" with 18.7% and "mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials" with 14.4% of the total imports. Even 68.8% of the foreign trade in 2014 was done with the EU which makes the Union by far the largest trading partner of Macedonia (23.3% with Germany, 7.9% with the UK, 7.3% with Greece, 6.2% with Italy, etc.). Almost 12% of the total external trade in 2014 was done with the Western Balkan countries.[150]

With a GDP per capita of US$9,157 at purchasing power parity and a Human Development Index of 0.701, Macedonia is less developed and has a considerably smaller economy than most of the former Yugoslav states.

According to Eurostat data, Macedonian PPS GDP per capita stood at 36% of the EU average in 2014.[151]

Infrastructure and e-infrastructure

Macedonia (along with Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo) belongs to the less-developed southern region of the former Yugoslavia. It suffered severe economic difficulties after independence, when the Yugoslav internal market collapsed and subsidies from Belgrade ended. In addition, it faced many of the same problems faced by other former socialist East European countries during the transition to a market economy. Its main land and rail exports route, through Serbia, remains unreliable with high transit costs, thereby affecting the export of its formerly highly profitable, early vegetables market to Germany. Macedonia's IT market increased 63.8% year on year in 2007, which is the fastest growing in the Adriatic region.[152]

Trade and investment

The outbreak of the Yugoslav wars and the imposition of sanctions on Serbia and Montenegro caused great damage to the Republic's economy, with Serbia constituting 60% of its markets before the disintegration of Yugoslavia. When Greece imposed a trade embargo on the Republic in 1994–95, the economy was also affected. Some relief was afforded by the end of the Bosnian war in November 1995 and the lifting of the Greek embargo, but the Kosovo War of 1999 and the 2001 Albanian crisis caused further destabilisation.

Since the end of the Greek embargo, Greece has become the country's most important business partner. (See Greek investments in the Republic of Macedonia.) Many Greek companies have bought former state companies in Macedonia,[153] such as the oil refinery Okta, the baking company Zhito Luks, a marble mine in Prilep, textile facilities in Bitola, etc., and employ 20,000 people. However, local cross-border trade between Greece and the Republic of Macedonia sees thousands of Greek shoppers visiting to purchase cheaper domestic products. The moving of business to Macedonia in the oil sector has been caused by the rise of Greece in the oil markets.[154]

Other key partners are Germany, Italy, the United States, Slovenia, Austria and Turkey.

Tourism

Tourism is an important part of the economy of the Republic of Macedonia. The country's abundance of natural and cultural attractions make it an attractive destination of visitors. It receives about 700,000 tourists annually.[155]

Demographics

The last census data from 2002 shows a population of 2,022,547 inhabitants.[5] The last official estimate from 2009, without significant change, gives a figure of 2,050,671.[156] According to the last census data, the largest ethnic group in the country are the ethnic Macedonians. The second largest group are the Albanians who dominated much of the northwestern part of the country, and are discriminated against. Following them, Turks are the third biggest ethnic group of the country where official census data put them close to 80,000 and unofficial estimates suggest numbers between 170,000 and 200,000. Some unofficial estimates indicate that in the Republic of Macedonia, there are possibly up to 260,000 Romani.[157]

Religion

Religion in Macedonia (2002)[158]

Eastern Orthodoxy is the majority faith of the Republic of Macedonia, making up 65% of the population, the vast majority of whom belong to the Macedonian Orthodox Church. Various other Christian denominations account for 0.4% of the population. Muslims constitute 33.3% of the population. Macedonia has the fifth-highest proportion of Muslims in Europe, after those of Kosovo (96%),[159] Turkey (90%),[160] Albania (59%),[161] and Bosnia-Herzegovina (51%).[162] Most Muslims are Albanians, Turks, or Romani, although few are Macedonian Muslims. The remaining 1.4% was determined to be "unaffiliated" by a 2010 Pew Research estimation.[163]

Altogether, there were 1,842 churches and 580 mosques in the country at the end of 2011.[164] The Orthodox and Islamic religious communities have secondary religion schools in Skopje. There is an Orthodox theological college in the capital. The Macedonian Orthodox Church has jurisdiction over 10 provinces (seven in the country and three abroad), has 10 bishops and about 350 priests. A total of 30,000 people are baptised in all the provinces every year.

Between the Macedonian and Serbian Orthodox Churches, there is a tension which arose from the former's separation and self-declared autocephaly in 1967. After the negotiations between the two churches were suspended, the Serbian Orthodox Church recognised a group led by Zoran Vraniškovski (also known as Archbishop Jovan of Ohrid), a former Macedonian church bishop, as the Archbishop of Ohrid.

The reaction of the Macedonian Orthodox Church was to cut off all relations with the new Ohrid Archbishopric and to prevent bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church from entering Macedonia. Bishop Jovan was jailed for 18 months for "defaming the Macedonian Orthodox church and harming the religious feelings of local citizens" by distributing Serbian Orthodox church calendars and pamphlets.[165]

The Macedonian Byzantine Catholic Church has approximately 11,000 adherents in Macedonia. The Church was established in 1918, and is made up mostly of converts to Catholicism and their descendants. The Church is of the Byzantine Rite and is in communion with the Roman and Eastern Catholic Churches. Its liturgical worship is performed in Macedonian.[166]

There is a small Protestant community. The most famous Protestant in the country is the late president Boris Trajkovski. He was from the Methodist community, which is the largest and oldest Protestant church in the Republic, dating back to the late 19th century. Since the 1980s the Protestant community has grown, partly through new confidence and partly with outside missionary help.

The Macedonian Jewish community, which numbered some 7,200 people on the eve of World War II, was almost entirely destroyed during the war: only 2% of Macedonian Jews survived the Holocaust.[167] After their liberation and the end of the War, most opted to emigrate to Israel. Today, the country's Jewish community numbers approximately 200 persons, almost all of whom live in Skopje. Most Macedonian Jews are Sephardic – the descendants of 15th-century refugees who had been expelled from Castile, Aragon and Portugal.

According to the 2002 Census, 46.5% of the children aged 0–4 were Muslim.[168]

Languages

The official and most widely spoken language is Macedonian, which belongs to the Eastern branch of the South Slavic language group. In municipalities where ethnic groups are represented with over 20% of the total population, the language of that ethnic group is co-official.[169]

Macedonian is closely related to and mutually intelligible with Standard Bulgarian. It also has some similarities with standard Serbian and the intermediate Torlakian and Shop dialects spoken mostly in southern Serbia and western Bulgaria (and by speakers in the north and east of Macedonia). The standard language was codified in the period following World War II and has accumulated a thriving literary tradition. Although it is the only language explicitly designated as an official national language in the constitution, in municipalities where at least 20% of the population is part of another ethnic minority, those individual languages are used for official purposes in local government, alongside Macedonian.

A wide variety of languages are spoken in Macedonia, reflecting its ethnic diversity. Besides the official national language, Macedonian, minority languages with substantial numbers of speakers are Albanian, Romani, Turkish (including Balkan Gagauz[170]), Serbian/Bosnian and Aromanian (including Megleno-Romanian).[171][172][173][174][175][176] There are a few villages of Adyghe speakers and an immigrant Greek community.[177][178] Macedonian Sign Language is the primary language of those of the deaf community who did not pick up an oral language in childhood.

According to the last census, 1,344,815 Macedonian citizens declared that they spoke Macedonian, 507,989 declared Albanian, 71,757 Turkish, 38,528 Romani, 6,884 Aromanian, 24,773 Serbian, 8,560 Bosnian, and 19,241 spoke other languages.[179]