Forest Theater

| Forest Theater | |

|---|---|

|

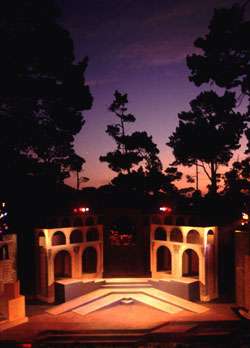

Sunset over the Forest Theatre during 1997 Carmel Shakespeare Festival production of Julius Caesar | |

Location in Carmel-by-the-Sea | |

| General information | |

| Type | Amphitheatre |

| Location | Santa Rita St, Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 36°33′13″N 121°55′00″W / 36.5535°N 121.9168°WCoordinates: 36°33′13″N 121°55′00″W / 36.5535°N 121.9168°W |

| Current tenants | year-round:Pacific Repertory Theatre seasonal: Forest Theater Guild |

| Opened | July 10, 1910 |

| Owner | City of Carmel-by-the-Sea |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | WPA |

| Website | |

| ForestTheaterGuild.org; ForestTheaterCarmel.org | |

The Forest Theater is an historic amphitheater in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. Founded in 1910, it is one of the oldest outdoor theaters west of the Rockies.[1] Actor/director Herbert Heron is generally cited as the founder and driving force, and poet/novelist Mary Austin is often credited with suggesting the idea.[2] As first envisioned, original works by California authors, children's theatre, and the plays of Shakespeare were the primary focus.[3] Since its inception, a variety of artists and theatre groups have presented plays, pageants, musical offerings and other performances on the outdoor stage, and the facility's smaller indoor theatre and school.

In 1937, the property was deeded to the City of Carmel-by-the-Sea in order to qualify for federal funding and, in 1939, the site became a WPA project. The WPA rebuilt the outdoor theatre and created an indoor facility beneath the outdoor stage,[4] the site re-opened as The Carmel Shakespeare Festival, with Herbert Heron as its Director, and, with the exception of the World War II years of 1943-44, the festival continued through the late-1940s. In 1949, Heron and twenty villagers started the first Forest Theatre Guild. In 1958, the City Council instituted an Arts Commission, charged with operation and maintenance of the Forest Theater.[5] The guild remained active until it disbanded in 1961, after which the outdoor theatre lay unused and neglected for over a decade.[6]

From 1968 to 2010, Marcia Hovick's Children's Experimental Theater leased the indoor theatre, which is now operated by Pacific Repertory Theatre's School of Dramatic Arts (SoDA).[6] In 1971, a second Forest Theater Guild was established by Cole Weston, and the group began producing summer musicals and community plays on the outdoor stage.[7]

In 1984, Pacific Repertory Theatre (PacRep) began producing classics, children's theater and musicals on the outdoor stage, reactivating Herbert Heron's Carmel Shakespeare Festival in 1990.[8] In 1997, The Forest Theater Guild added the Films in the Forest movie series, featuring cinema favorites from classics such as It's a Wonderful Life to feature films like Frozen. In 2005, PacRep presented the theater's highest-attended production, Disney's Beauty and the Beast, to a combined audience of over 10,000 ticket holders.[9]

On April 23, 2014, the facility was shuttered due to health and safety issues caused by years of deferred maintenance. In a special workshop on May 5, the community and city council declared a "cultural community emergency"[10] developing a quick consensus that the historic facility should be reopened as soon as possible. As of February 2016, however, the theater remained closed.

Herbert Heron

Herbert Heron came to Carmel in 1908. He had worked extensively on the stage in Los Angeles and came from a background of writers and dramatists. On a visit from Los Angeles, Heron fell in love with the village by the sea. He soon settled in Carmel, bringing with him his young bride Opal Heron, the daughter of a Polish Count.

In 1910, the Herons found a concave hillside looking out, surrounded by oaks and pines, and thought it would be an ideal space for an outdoor theater. Heron’s idea was to stage plays by Carmel authors starring local residents – a true community theater. He approached Frank Devendorf, co-founder of the Carmel Development Company, and asked about purchasing the plot for such a purpose. Devendorf, wanting to attract artistic spirits and "brain workers" to the nascent village, i.e. teachers, librarians, etc., agreed and let Heron have the space rent-free.

By February 1910, construction began on the theater. It was a simple plan: a wooden proscenium stage with a scrim of pines and plain wooden benches. Meanwhile, Heron was busying organizing the first production with the help of the newly minted Forest Theater Society.

The first theatrical production, David and Saul, a biblical drama by Constance Lindsay Skinner under the direction of Garnet Holme of Berkeley, inaugurated the Forest Theater on July 9, 1910.[11] Reviewed in both Los Angeles and San Francisco it was reported that over 1,000 theatergoers attended the production.[12][13][14]

There was no electricity at the theater – calcium floodlights were brought by covered wagon from Monterey to light the stage.[15] Two bonfires were also lit on opposite ends of the proscenium, a tradition which continues today.

Forest Theater Society, Western Drama Society & Carmel Arts & Crafts Club

The Forest Theater Society produced several plays in the next few years. Of note was the 1912 production of The Toad, a play written by Bertha Newberry, the wife of Perry Newberry, an early Carmel leader. Also produced that year was the first children's play staged at the Forest Theater, Alice in Wonderland, adapted by Newberry and Arthur Vachell. There was so much enthusiasm for live theater, and varying ideas on how the Forest Theater should be run, that two additional theater groups began participating – The Western Drama Society (including Heron and other members of the Forest Theater Society), whose goal was to focus on California authors, and the already-established Arts and Crafts Club, which had been active in the town since 1905.

In 1913 theatergoers witnessed four new productions: the Robin Hood drama entitled Runnymede, Newberry’s play for children Aladdin, Mary Hunter Austin’s Fire starring George Sterling and directed by Austin herself, and Takeshi Kanno’s poem-play Creation-Dawn.[16] A troublesome split in the ranks of the theater literati caused Sterling and Heron to found an alternative theater society, the California (or Western) Drama Society; the factions were eventually reconciled and returned to the Forest Theater.[11] In 1915 – a season that boasted 11 separate productions – audiences saw the premiere of Newberry’s Junipero Serra, a historical pageant focusing on the life of Father Junípero Serra. In 1916 two of the celebrated productions were Yolanda of Cyprus and The Piper, in which four Carmel artists acted and painted scenery: Arthur Vachell, Mary DeNeale Morgan, William Frederic Ritschel, and Laura Maxwell.[17][18][19] Other Carmel artists who volunteered their time as actors and set designers include: Cornelius Botke, Ferdinand Burgdorff, Theodore Criley (remembered today for his “duel” outside the theater with Harry Leon Wilson), Josephine Culbertson, Homer Emens, William Kegg, Xavier Martinez, Paul Mays, Jo Mora, Ira Remsen, Herman Rosse, George Seideneck, William Silva, and Hamilton Wolf.[11] The ensuing decade saw the Forest Theater reach the height of production, with 50 plays and musicals staged between 1915 and 1924, including a 1922 production of Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra, when director Edward G. Kuster was almost run out of town for erecting a giant backdrop that hid Carmel’s beloved canopy of trees. Kuster defended himself admirably, noting that the play was, after all, set in a desert!

Unfortunately, this overabundance of plays became a serious strain on resources, such as players, donations and attendees, which were, understandably, spread thin. Inevitably, factional strife erupted between the groups and the quality of theater in Carmel began to decline. In 1923, in order to solve this dilemma and rebuild a healthy theater scene, the competing producing organizations disbanded, and under the auspices of the Arts and Crafts Club, the Forest Theater Corporation was created as a unifying entity to produce and manage the plays staged at the Forest Theater.[20][21]

Once again, the picturesque outdoor theater became extremely popular in the small village and everyone, it seemed, added to the creative process. The town’s many carpenters and woodworkers built highly intricate sets; those handy with a thread and needle created costumes. And just about everyone found their way on stage. Productions at the Forest Theater were truly a village affair. The resulting success enabled the Forest Theater Corporation to buy the land from the Carmel Development Company in 1925.[22] The Forest Theater Corporation continued to produce plays throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. While the state of theater in Carmel was in a precarious position due to a glut of indoor theaters and theatrical companies, the Forest Theater continued to flourish. In 1934, the Forest Theater saw its 100th major production, The Man Who Married a Dumb Wife, by Anatole France. Heron directed the comedy, which featured set and costumes designs by Helena Heron.

Great Depression

The Great Depression struck and it affected all aspects of local life. When repairs were needed and no money could be found from local donors, the idea of applying for Works Progress Administration money was proffered. Funds were only available to government entities and the private non-profit Forest Theater was not eligible. In 1937, it was decided to deed the Forest Theater to the City of Carmel-by-the-Sea in order to obtain WPA funds for major renovations. Improvements to the facility included building new benches, laying a concrete foundation for the stage, and replacing the surrounding barbed-wired fences with a traditional grape-stake fence. The Forest Theatre was unused during the three years of renovations.[5]

Carmel Shakespeare Festival

With a rejuvenated space, the Forest Theater was ready to get back into the theater business. The works of Shakespeare had proven highly popular beginning with Heron’s 1911 production of Twelfth Night, and upon completion of the WPA project, Heron formally resumed productions with the inauguration of the Carmel Shakespeare Festival in 1940. The festival offered Shakespeare, including Macbeth, Hamlet, Julius Caesar and As You Like It, as well as the works of Carmel authors, including the first local production of Robinson Jeffers' The Tower Beyond Tragedy. With the advent of World War II, however, mandatory blackouts were ordered for coastal towns and cities. The residents of Carmel participated and halted all Forest Theater activity, essentially closing the facility in 1943-44, and again in 1946.[22] From 1947-1949, the facility resumed annual productions of Shakespeare and local authors. The Carmel Shakespeare Festival was reactivated in 1990 Pacific Repertory Theatre (see below).

Forest Theater Guild

Throughout this time, Herbert Heron maintained his intense involvement with the Forest Theater, continuing to write, produce, direct and star in productions. Growing tired of the constant activity, Heron retired from active involvement. Theater was in Heron's blood, though, and he could not completely leave the theater behind. As part of deeding the Forest Theater to the City of Carmel-by-the-Sea, the City took over responsibility for the physical plant. Realizing that a supporting organization was needed for the City-owned facility, Heron organized and co-founded the Forest Theatre Guild in 1949.[23] Guided by Cole Weston and Philip Oberg, the Forest Theater Guild began to produce plays by local authors, Shakespeare, and classic drama. In 1961, the original Forest Theater Guild ceased operations.[6]

End of Heron era

In 1960, Herbert Heron finished his 50th year with the Forest Theater with his own play, Pharaoh. By 1963 the theater had shown over 140 plays, including 64 premieres and dramatizations by California authors. Numbered among these productions were those by Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw, Greek tragedies, local history, children's plays, light operas and musical comedies. Following a brief illness Herbert Heron died on January 8, 1968, at the age of 84.

Unfortunately, despite some continued play production, parts of the theater were left in disrepair. Upkeep was not maintained by the City and, during the mid-1960s, the wood in the stage and seating rotted and the grounds became rundown. By this time, the Forest Theater Guild had closed and abandoned the facility, and, with a few minor exceptions, no plays were being shown on the main stage. The City began to use the site for other purposes, such as a Boy Scout camp, and a corporate yard. The Cultural Commission recommended to the City that either repairs should be made to the aging Forest Theater, or it should be unloaded from the City's holdings. At that time, no action was taken. In 1966 the usefulness of the Forest Theater was discussed at City Council during the 1966-1967 budget meetings.[24] Discussions included whether it was cost effective to keep the theater, resulting in an uproar by Carmelites determined to save the historic site. In 1968, to keep the Forest Theater in use, Cole Weston, who had then become the city’s first Cultural Director, leased the Theater-in-the-Ground to the then-homeless Children's Experimental Theatre.

Children's Experimental Theater

In 1968, the Children's Experimental Theatre (CET), began leasing the indoor theater. Formed in 1960 by Marcia Hovick to develop "creative confidence" through theatre training, CET had been using space at the Golden Bough Playhouse and Sunset Center, and needed a permanent place for their activities.[25] In 1969, Hovick formed a new production entity called the Staff Players Repertory Company, staging classic drama on the small Indoor Forest Theater stage. In 2010, after 50 years of continuous business, CET ceased operations. The lease on the school was then given to Pacific Repertory Theatre for its ten year old School of Dramatic Arts.[6]

Threat of Closure and revival of Forest Theater Guild

In spite of this new use of the Forest Theater, the main stage remained dark and, once again, reservations about the usefulness of the theater were voiced. In 1971, the Cultural Commission considered closing the theater for good.[26] Again, the residents of Carmel rose up and voiced their opposition. A second Forest Theater Guild was created, this time as a nonprofit organization, with former president Cole Weston as the new Guild President.[27] In order to raise needed funds, as well as draw attention to the possible closure, the new group produced a staged reading of Robinson Jeffers’ Medea and The Tower Beyond Tragedy, which featured a noted performance by actress Dame Judith Anderson.[6]

In 1972, the Guild officially incorporated,[28] and staged their first full production, producing Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. The success of this production showed the City that there was still public interest and support for the Forest Theater. The City Council commissioned a study to evaluate the efficacy of the theater.[29] The public was invited to comment and, after several months of often heated discussions, several recommendations were made: The City Council decided to continue city operation of the facility, and the outdoor theater would be leased to the Forest Theater Guild on a two-year trial basis. The trial was a success, and the lease with the Forest Theater Guild was renewed. Over the next several decades, the Guild produced over 20 major plays, including Moon for the Misbegotten and A Long Day’s Journey into Night. In 1997, the guild began Films in the Forest, a series of first-run movies, classic feature films, and documentary film screenings. These cinema favorites included classics such as Band Wagon and family favorites such as Finding Nemo.[30]

Pacific Repertory Theatre

In 1984, a new organization joined the Forest Theater community, GroveMont Theatre. GroveMont was founded in 1982 by Stephen Moorer, who had participated in the Children's Experimental Theatre program, and had also acted in Forest Theater Guild productions. In 1984, at the request of the Carmel Cultural Commission, GroveMont began producing shows at the Forest Theater, staging Jeffers’ Medea, starring local actress Rosamond Goodrich Zanides.[31]

In 1990, Moorer reactivated the old Carmel Shake-speare Festival of the 1940s, adding the hyphen in "Shake-speare" to denote interest and support research into the Shakespeare Authorship Question. In 1993, the company changed its name to Pacific Repertory Theatre (PacRep), becoming the only professional theater company in residence at the Forest Theater,[32] continuing to stage productions at the Forest Theater every September and October, expanding into August in 2000. In 2011, following the closure of the 50-year-old CET, the City of Carmel awarded the year-round lease of the indoor Forest Theater to PacRep for its educational SoDA program.[33]

Pacific Repertory Theatre’s annual family musicals have included “high-flying” technology for productions of Peter Pan and The Wizard of Oz. Among the many successful productions at the Forest Theater over the years, 2006’s Disney’s Beauty and the Beast proved to be a benchmark for attendance records. Directed by Walt DeFaria and produced by Moorer, the musical sold over 10,000 tickets.[9]

2014 closure

On April 23, 2014, the facility was shuttered due to health and safety issues caused by years of deferred maintenance.[34] In a special workshop on May 5, 2014, after declaring a "cultural community emergency", the city decided that the historic facility should be reopened as soon as possible.

In January 2015, however, anticipating delays in the renovation schedule, the city announced that the reopening of the theatre would be postponed until 2016, and that an agreement was reached with the theater companies that cancelled the 2015 season in the interest of getting the work "done right". After a contentious design period, which raised "concerns about the architect's ADA compliance plan", the 2-phase project was approved in a rare split-vote of the city council.[35] Phase 1 of the renovation will address the "red tag issues" and ADA compliance requirements, while phase 2 is slotted to upgrade concessions and restroom facilities, and to make other improvements.[36]

See also

References

- ↑ Carmel at Work and Play, Bostick, 1977

- ↑ Carmel's Forest Theater, by Michael Williams, Pacific Monthly, 1912

- ↑ Carmel Today and Yesterday, Bostick, 1945

- ↑ William R. Lawson. "Achievements, Federal Works Agency. Work Projects Administration, Northern California." 1940: 89.

- 1 2 http://ci.carmel.ca.us/carmel/index.cfm/linkservid/A836D277-3048-7B3D-C52E40C677DF9680/showMeta/0/

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Forest Theater a 'bohemian grove' for Shakespeare fans – Page 2 of 2". The San Francisco Chronicle. August 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Cole Weston Elected President; Forest Theater Guild Maps Ambitious Program." Monterey Peninsula Herald, July 29, 1971

- ↑ Shakespeare Companies and Festivals: An International Guide By Ron Engle, Felicia Hardison Londré, Daniel J. Watermeier. Entry on Carmel Shakespeare Festival by Philip Clarkson

- 1 2 http://www.montereybayadventures.com/carmelbythesea/ci_12890610

- ↑ http://www.ksbw.com/news/plans-underway-to-reopen-carmels-forest-theatre/25843110

- 1 2 3 Edwards, Robert W. (2012). Jennie V. Cannon: The Untold History of the Carmel and Berkeley Art Colonies, Vol. 1. Oakland, Calif.: East Bay Heritage Project. pp. 49, 124, 144, 179, 191, 197, 201, 326, 346, 360–61, 364, 381, 414, 465, 495, 500, 502, 523, 528 547, 587, 595, 609, 617–18, 621, 627, 653–54, 671. ISBN 9781467545679. An online facsimile of the entire text of Vol. 1 is posted on the Traditional Fine Arts Organization website (http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/10aa/10aa557.htm).

- ↑ Monterey Daily Cypress: 29 May 1910, p.1; 19 June 1910, p.1; 19 July 1910, p. 1.

- ↑ San Francisco Call: 3 July 1910, p. 37-38; 10 July 1910, p.39.

- ↑ Barman, Jean. Constance Lindsay Skinner. University of Toronto Press, 2002.

- ↑ Letter to Richard N. Palmer from Herbert Heron, June 12, 1963. Harrison Memorial Library, Herbert Heron Collected Papers.

- ↑ San Francisco Examiner: 27 April 1913, p.45; 25 May 1913, p.46; 29 June 1913, p.44; 27 July 1913, p.71; 17 August 1913, p.35.

- ↑ Christian Science Monitor, 25 July 1916, p. 6.

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle, 25 June 1916, p.21.

- ↑ The Wasp (San Francisco, CA), 8 July 1916, p. 11.

- ↑ Carmel Pine Cone, 15 September 1923, p. 1.

- ↑ Bostick, Daisy and Castelhun, Dorthea. Carmel at Work and Play, The Seven Arts, 1925.

- 1 2 Cf. Letter to Palmer, June 1963.

- ↑ “David Prince to head newly organized Forest Theater Guild.” May 9, 1949. Harrison Memorial Library, Nixon File Forest Theater #11.

- ↑ "Forest Theater given support." Monterey Peninsula Herald, August 4, 1966.

- ↑ Nichols, Kathryn M. “40… and still going strong.” Monterey County Herald, September 7, 1999.

- ↑ Nickerson, Roy. "Is Forest Theater’s usefulness outlived?" Monterey Peninsula Herald, June 2, 1971.

- ↑ "Forest Theater Guild Celebrates Elected President." Monterey Peninsula Herald, Aug. 3, 1971

- ↑ http://www2.guidestar.org/organizations/23-7227328/forest-theatre-guild.aspx#

- ↑ Forest Theater Committee of the Cultural Commission, City of Carmel-by-the-Sea. “Report on the Forest Theater.” December 4, 1971.

- ↑ "Films in the Forest at Outdoor Forest Theater". The Monterey County Weekly.

- ↑ Blum, Terry (January 2002). "Spotlight On Carmel Stephen Moorer". Mctaweb.org, Monterey County Theatre Alliance. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ↑ "Pacific Repertory Theatre", Theatre Bay Area website, accessed July 23, 2009

- ↑ http://www.pineconearchive.com/110204PCA.pdf, page 2A

- ↑ Ryce, Walter. "Inspectors shut down Forest Theater as an 'unsafe structure.'" Arts & Culture Blog, Monterey County Weekly, April 24, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.montereyherald.com/article/NF/20150804/NEWS/150809932

- ↑ Ryce, Walter. "The city of Carmel announces the Forest Theater will not reopen this summer, but in 2016." Arts & Culture Blog, Monterey County Weekly, January 29, 2015.