Ford FE engine

| Ford FE V8 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Ford Motor Company |

| Also called | Ford FT V8 |

| Combustion chamber | |

| Configuration | OHV V8 |

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | Ford Y-block V8 |

| Successor |

Ford 335-series engine Ford 385-series engine |

The Ford FE engine is a Ford V8 engine used in vehicles sold in the North American market between 1958 and 1976. The FE was introduced to replace the short-lived Ford Y-block engine, which American cars and trucks were outgrowing. It was designed with room to be significantly expanded, and manufactured both as a top-oiler and side-oiler, and in displacements between 330 cu in (5.4 L) and 428 cu in (7.0 L).

"FE" derives from 'Ford-Edsel.'[1] Versions of the FE line designed for use in medium and heavy trucks and school buses from 1964 through 1978 were known as "FT," for 'Ford-Truck,'[2] and differed primarily by having steel (instead of nodular iron) crankshafts, larger crank snouts, different distributor shafts, different water pumps and a greater use of iron for its parts.

Use

The FE series engines were used in cars, trucks, buses, and boats, as well as for industrial pumps and other equipment. Ford produced the engine from 1958 and ceased production in 1976. Aftermarket support has continued, with replacement parts as well as many newly engineered and improved components.

In Ford vehicles, the FE primarily powered full and midsize cars and trucks. Some of the models in which the FE was installed:

Ford Galaxie, Ford Custom 500, Ford Mustang, Ford Thunderbird - 3rd generation, Ford Thunderbird - 4th generation, Ford LTD, Ford Torino, Ford Ranchero, Ford Talladega, Ford Fairlane, Ford Fairlane Thunderbolt, and F-Series trucks though typically only those 1 ton and lesser in capacity.

In addition to its use in Ford and Mercury branded vehicles, the FE was also sold to third parties for use in their own products such as buses, and boats. In addition, the FE was used to power irrigation pumps, generators and other machinery where long-running, low-rpm, reliable service was required.

Ford regularly made updates to the design of the FE which appear as engineering codes or variations in casting numbers of parts. In addition to production casting codes, Ford also made use of "SK" and "XE" numbers if the parts were one-offs or developmental designs not approved for production. Many parts attached to Ford's racing engines carried SK and XE numbers.

Marine

The FE block was manufactured using a thinwall casting technique, where Ford engineers determined the required amount of metal and re-engineered the casting process to allow for consistent dimensional results. A Ford FE from the factory weighed 650 lb (295 kg) with all iron components, while similar seven-liter offerings from GM and Chrysler weighed over 700 lb (318 kg). With an aluminum intake and aluminum water pump the FE could be reduced to under 600 lb (272 kg). This weight saving was significant to boaters and racers. The FE was popular in V-drive marine applications, available as a factory option in Chris Craft boats.

Beginning in 1968, the U.S. Navy SEALS used twin 427 FEs to power their light SEAL support craft (LSSC).[3]

Racing

.jpg)

Specific models that used FE engines include the AC Cobra MKIII, GT40s, the AC Frua, as well as various factory racing versions of Ford Mustangs, Ford Galaxies, Ford Fairlanes, and Ford Thunderbirds.

In the 1960s, most organized racing events required either stock components or components that were readily available to the general public. For NASCAR racing, rules required that at least 500 vehicles be sold to the general public equipped as raced. Many drag racing and road racing organizations had similar rules, which contributed to a wide range of performance parts being made available through Ford dealership parts counters. In addition, aftermarket suppliers produced performance parts and accessories.

The use of the FE by Ford itself as the powerplant in many of its racing programs and performance vehicles resulted in constant improvements and engineering changes over the course of its life. Racing-inspired changes to the FE which later made it to production engines included the side-oiler block, which directed oil first to the lower portions of the block.

Road and track racing

In 1963, the 427 Galaxies dominated NASCAR. Tiny Lund won the biggest race of the year, the Daytona 500, with 427s finishing first through fifth. Ford won 23 races to Plymouth's 19. The Plymouths earned all their victories on the short tracks while Ford dominated the super speedways, Chevrolet finished with eight wins and Pontiac had four.

In 1964, Ford had their best season ever, with 30 wins. Dodge was second with 14, while Plymouth had 12. Adding the five wins that Mercury had, the 427 had a total of 35 NASCAR Grand National wins for the 1964 season. Fred Lorenzen won the Atlanta 500 and proceeded to beat Dodges and Plymouths, which were using 426 Hemi engines, in six of the next seven races. Ford was using the high-riser intake and matching heads, which were allowed by NASCAR for one season (1964).

In 1965, NASCAR banned Ford's high-riser engines [4] claiming they did not fit under "stock" hoods, allowing Chrysler to continue racing its 426 Hemi, which had never been installed in a production vehicle until that year.[5] Also in 1965, Ford developed its own version of a hemi-chambered engine. The 427 "Cammer" used a pair of overhead cams to operate the valves in its hemi. NASCAR banned the engine. Then Ford developed the medium-riser intake and head, which fit under stock hoods and was accepted by NASCAR. Ned Jarrett, driving for Ford, was the 1965 Grand National champion and Ford won the NASCAR crown.

Also in 1965, Ford and Carroll Shelby began production of a new and improved Cobra using a 427 cubic inch (7.0 L) FE side-oiler in place of the original's 289 cubic inch Windsor small-block. A new chassis was built enlarging 3" main tubing to 4", with coil springs all around. The new car also had wide fenders and a larger radiator opening. The S/C (for semi-competition) "street" engine was rated at 425 bhp (317 kW), which provided a top speed of 164 mph (262 km/h), and the competition version 485 bhp (362 kW) with a top speed of 185 mph (298 km/h). Cobra Mark III production began on 1 January 1965, and was used for racing into the 1970s. An original S/C sold in 2011 for 1.5 million USD, making it one of the most valuable Cobra variants.[6]

In 1966, the 427 cubic inch Ford GT40 Mk II dominated the 24 Hours of Le Mans race, with a one-two-three result.

In 1967, Parnelli Jones, in a Holman-Moody prepped Fairlane, won the season-opening Riverside 500 road race. Then, Mario Andretti captured the Daytona 500 in a Fairlane, with Fred Lorenzen a close second in his Holman-Moody Ford. The FE again powered the 24 Hours of Le Mans winner. In 1968, the rules of the race were changed, limiting displacement to 302 cubic inches under certain circumstances. Ford won the following two years using its Ford Windsor smallblock in the GT40.

Ford's racing partner, privately owned Holman-Moody, also developed a version of the FE for the Can-Am racing series. It used factory supplied tunnel port heads, a mechanical fuel injection system mounted on a crossram intake manifold, and a revised dry sump oiling system, but met with only limited success.

Drag racing

Organized drag racing (NHRA, AHRA and even NASCAR dabbled in drag racing in the mid-1960s) was a major venue for the FE in its various forms. Many of the most innovative products were developed and used for 1/4 mile drag racing as aftermarket suppliers eagerly supported the engine design with products such as special intakes, camshafts, superchargers, manifolds, cylinder heads, water and fuel pumps, and exhaust headers. But it was the Ford company itself which developed the most potent products and platforms for the drag-racer. Beginning in 1962 and continuing through 1964, Ford made lightweight versions of its popular Galaxie model using aluminum, fiberglass and specially chosen components emphasizing light weight over comfort or style. Many parts were simply not put on the vehicle, such as a passenger side windshield wiper, sound deadening, armrests, heater, and radio.

In late 1964, Ford contracted Holman & Moody to prepare ten 427-powered Mustangs to contest the National Hot Rod Association's (NHRA) A/Factory Experimental Class in the 1965 drag racing season. Five of these special Mustangs made their competition debut at the 1965 NHRA Winternationals, where they qualified in the Factory Stock Eliminator Class. The car driven by Bill Lawton won the class.[7]

For the 1964 model year, Ford introduced the two-door Fairlane 500 sedan-based Thunderbolt. Modified to accept a 427 high-riser engine, it featured a teardrop-shaped bubble hood to clear the induction system and drivetrain components from the larger Galaxie model. The two inner headlights were eliminated and replaced with air inlets ducted directly to the two four-barrel carbs. It was an industry first, the only time that a turn key drag car was made available to the general public.[8] However, the extensive modifications to the car did not meet Ford appearance quality standards.[9][10][nb 1]

The 1964 NHRA Super Stock title was captured with a Thunderbolt.[11] Nearly half a century later, in 2013, a Thunderbolt set a new SS/A record of 8.55 seconds in the quarter mile, with a closing speed of 154 mph,[12]

In 1963, Dick Brannan set the NHRA Super/Stock National record at 12.42 on a hot July day. In the biggest race of the year, the INDY Nationals, Ed Martin's lightweight Galaxie lost the Super Stock trophy run to John Barker's Dodge but at the teardown, the Dodge was found to have an illegal cam. In drag racing, the 427 Ford Galaxie was a winner in three consecutive National Events: the '64 Indy Nationals, the 1965 WinterNationals and the 1965 Indy Nationals. It was Mike Schmitt driving the Desert Motors Galaxie to the AA/SA Class win at the 1964 Indy Nationals. At the 1965 Winternationals it was a clean sweep as Doug Butler's four-speed took the win in AA/S with a 12.77 @ 114.21 and Bill Hanyon won on the automatic side with a 12.24 @ 117.95. Additionally, Bud Schellenberger's "Double A Stock" 1964 Galaxie was the 1965 Indy Nationals Top Stock Eliminator with a 12.16 @ 114.21. The Shelby Super Snake top fuel dragster, powered by a 427 supercharged SOHC, became the first car in NHRA competition to break the six-second quarter-mile time barrier. It was the winner of the 1966 NHRA Spring Nationals. In every decade since, the FE has held drag-racing records. In 2011, the new decade opens with the NHRA SS/F (class rules include stock compression ratio, stock valve sizes, stock carb sizing and other OEM-type equipment limitations) national record: the quartermile in 9.29 seconds, with a closing speed of 143.63 mph.

Other closed course racing

In 1970, an FE-powered vehicle set the land speed record for the U.K. Tony Densham set the new British land speed record of just over 207.6 mph (334.1 km/h) over the flying kilometer (the average of two runs in opposite directions within an hour) and then held onto the record for over 30 years. The FE-powered vehicle beat the official British wheel-driven record over the flying 500 and kilometer distances, until then held by Sir Malcolm Campbell, of 174.883 mph[13]

Custom automobiles

The FE engine is used extensively in custom installations. The extensive availability of multi-carburetor and other exotic intakes, as well as many other "dress-up parts", has contributed to its use where the engine would be shown off. FEs powered the original Batmobiles built by George Barris for the 1966 TV series. It fit under the hood along with the Bat-ray, Bat-ram, a nose-mounted aluminum chain slicer and all the associated support hardware of the 5,500 pound vehicle. One dragstrip version was equipped with a Holman-Moody prepped 427 FE with dual quads, which would be launched in second gear and spin its tires the entire quarter-mile length of the track.[14] In 1968 Carroll Shelby created a custom Mustang using a California Special model and an experimental Ford 428 FE (known as a CJX, precursor to the 428 Cobra Jet). This "Green Hornet"[15] had a custom independent rear suspension, four-wheel disc brakes and a Conelec electronically controlled port fuel injection system. It had a 5.7 sec 0-60 time and 157 mph top speed, versus a factory 428 cu in FE Shelby GT500's 6.5 second 0-60 and 128 mph top speed.[16][17]

Pair of FEs used in an Ed Roth custom

Pair of FEs used in an Ed Roth custom

2011 Ridler Award winner - 1956 Ford Sunliner with an FE SOHC (Cammer)[18]

2011 Ridler Award winner - 1956 Ford Sunliner with an FE SOHC (Cammer)[18]

Description

The FE and FT engines are Y-block designs— so-called because the cylinder block casting extends below the crankshaft centerline, giving great rigidity and support to the crankshaft's bearings. In these engines, the casting extends 3.625 in (92.1 mm) below the crankshaft centerline, which is more than an inch below the bottom of the crank journals.

Blocks were cast in two major groups: top-oiler and side-oiler. The top-oiler block sent oil to the top center first, the side-oiler block sent oil along a passage located on the lower side of the block first.

All FE and FT engines have a bore spacing (distance between cylinder centers) of 4.630 in (117.6 mm), and a deck height (distance from crank center to top of block) of 10.170 in (258.3 mm). The main journal (crankshaft bearing) diameter is 2.749 in (69.8 mm). Within the family of Ford engines of the time, the FE was neither the largest nor smallest block.

| Displacement | Type | Bore+0.0036/-0.0000 | Stroke+/-0.004 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 330 cu in (5.4 L) | FT | 3.8750 in (98.43 mm) | 3.500 in (88.9 mm) |

| 332 cu in (5.4 L) | FE | 4.0000 in (101.60 mm) | 3.300 in (83.8 mm) |

| 352 cu in (5.8 L) | FE | 4.0000 in (101.60 mm) | 3.500 in (88.9 mm) |

| 359 cu in (5.9 L) | FT | 4.0500 in (102.87 mm) | 3.500 in (88.9 mm) |

| 360 cu in (5.9 L) | FE | 4.0500 in (102.87 mm) | 3.500 in (88.9 mm) |

| 361 cu in (5.9 L) | FE | 4.0500 in (102.87 mm) | 3.500 in (88.9 mm) |

| 361 cu in (5.9 L) | FT | 4.0500 in (102.87 mm) | 3.500 in (88.9 mm) |

| 389 cu in (6.4 L) | FT | 4.0500 in (102.87 mm) | 3.784 in (96.1 mm) |

| 390 cu in (6.4 L) | FE | 4.0500 in (102.87 mm) | 3.784 in (96.1 mm) |

| 391 cu in (6.4 L) | FT | 4.0500 in (102.87 mm) | 3.786 in (96.2 mm) |

| 396 cu in (6.5 L) | FE | 4.2328 in (107.51 mm) | 3.514 in (89.3 mm) |

| 406 cu in (6.7 L) | FE | 4.1300 in (104.90 mm) | 3.784 in (96.1 mm) |

| 410 cu in (6.7 L) | FE | 4.0500 in (102.87 mm) | 3.984 in (101.2 mm) |

| 427 cu in (7.0 L) | FE | 4.2328 in (107.51 mm) | 3.784 in (96.1 mm) |

| 428 cu in (7.0 L) | FE | 4.1300 in (104.90 mm) | 3.984 in (101.2 mm) |

| Small block | Medium block | Big block | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spacing | Displacement | AKA | Spacing | Displacement | AKA | Spacing | Displacement | AKA | |||

| 4.38" | 239 in³ | Y-block | 4.63" | 332 in³ | FE | 4.90" | 383 in³ | MEL | |||

| 4.38" | 272 in³ | Y-block | 4.63" | 352 in³ | FE | 4.90" | 410 in³ | MEL | |||

| 4.38" | 292 in³ | Y-block | 4.63" | 360 in³ | FE | 4.90" | 430 in³ | MEL | |||

| 4.38" | 312 in³ | Y-block | 4.63" | 390 in³ | FE | 4.90" | 462 in³ | MEL | |||

| 4.38" | 260 in³ | Windsor | 4.63" | 406 in³ | FE | 4.90" | 429 in³ | 385-series | |||

| 4.38" | 289 in³ | Windsor | 4.63" | 410 in³ | FE | 4.90" | 460 in³ | 385-series | |||

| 4.38" | 302 in³ | Windsor | 4.63" | 427 in³ | FE | ||||||

| 4.38" | 351 in³ | Windsor | 4.63" | 428 in³ | FE | ||||||

| 4.38" | 302 in³ | 335-series | 4.63" | 330 in³ | FT | ||||||

| 4.38" | 351 in³ | 335-series | 4.63" | 361 in³ | FT | ||||||

| 4.38" | 400 in³ | 335-series | 4.63" | 391 in³ | FT | ||||||

Because the FE was never a completely static design and was constantly being improved by Ford, references to a particular version of the FE can become difficult. Generally though, most FEs can be described using the following descriptors:

1) Carburetor count, i.e. single 2V (two-barrel), single 4V, dual quad (two 4V carburetors), tripower (three 2V carburetors) or Weber (four 2V Weber carburetors).

2) Top-oiler or side-oiler block (though there are known instances of side-oiler blocks drilled at the factory as top-oilers; perhaps to salvage blocks with quality control issues that prevented them from being completed as side-oilers).

3) Head type: low-riser, medium-riser, high-riser, tunnelport, or SOHC. These descriptions actually refer to the intakes used with the heads...a low-riser intake, designed to fit under a low hoodline was the earliest design. The high-riser intake required a bubble in the hood of cars it was installed in for clearance. While the low and medium riser heads could be used in combination with either low or medium riser intakes, the high riser head required a high-riser intake due to the increased height of the intake port. The medium riser's intake port is actually shorter in height, though wider, than the low-riser's port. The high-riser's ports are taller than either the low or medium-riser ports. Low-riser intakes have the carburetor placed relatively low so that the air-fuel mix must follow a more convoluted path to the chamber. A high-riser's intake places the carburetor approximately 6 in (152 mm) higher so the air-fuel mixture has a straighter path to the chamber. The tunnelport and SOHC heads both bolted onto FE blocks of either variety but required their own matching intakes. Within the major head groups, there were also differences in chamber designs, with small chambers, machined chambers and large chambers. The size and type of chamber affected the compression ratio, as well as the overall performance characteristics of the engine.

Generation 1

332

The smallest displacement FE engine was the 331.8 cu in (5.4 L) "332", with a 4.0 in (101.60 mm) bore and 3.3 in (83.82 mm) stroke. It was used in Ford-brand cars in 1958 and 1959, domestically marketed U.S.- and Canadian-built Edsel-brand cars in 1959, and in export-configured 1958 and 1959 Edsels.[19][20][21][22] The two-barrel version produced 240 bhp (179.0 kW), a Holley or Autolite four-barrel version 265 bhp (197.6 kW).

332 engine configurations and applications

1st generation FE block shouldn't be confused with 352, 383, 390, 430 Mercury MEL blocks, which had a wedge shaped combustion chamber is in their blocks, not in the head as in FE blocks.

- 4V, 9.5:1 — 265 bhp (197.6 kW) at 4600 rpm and 360 lb·ft (488 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1958 Ford

- 1958 Edsel Ranger, Pacer, Villager, Roundup and Bermuda overseas export vehicles only

- 2V, 8.9:1 — 225 bhp (167.8 kW) at 4600 rpm and 325 lb·ft (441 N·m) at 2200 rpm

- 1959 Ford

- 1959 Edsel Corsair and Villager, standard equipment, (called "Express V8")[19]

352

Introduced in 1958 as part of the Interceptor line of Ford V8 engines, the Ford 352 of 351.9 cu in (5.8 L) actual displacement was the replacement for the Lincoln Y-block. It is a stroked 332 with 3.5 inches (88.90 mm) stroke and a 4 inches (101.60 mm) bore, and was rated from 208 bhp (155.1 kW) with a 2-barrel carburetor to over 300 bhp (223.7 kW) on the 4-barrel models. When these engines were introduced, they were called Interceptor V-8 on the base models and Interceptor Special V-8 on the 4-barrel models.[20] The 1958 H vin coded 352 was designated as Interceptor V-8 Thunderbird Special according to the 1958 Ford V8 Cars & Thunderbird Service Manual pg 483. The Interceptor was the base-performance engine in 1958. For the 1959 model year, the FE engine series was renamed the Thunderbird V-8 and the Thunderbird Special V-8.[21] When installed in Mercury vehicles, these engines were named "Marauder". This series of engines usually weighed over 650 lb (295 kg).[23] In 1960 Ford created A High Performance version of the 352 rated at 360 horsepower (270 kW) it featured an aluminum 4bbl intake manifold, A Holley 4160 Carburetor, cast iron "header" style exhaust manifolds, 10.5:1 compression ratio and A solid lifter valve train.

352 engine configurations and applications

- 2V

- 8.4:1 — 208 horsepower (155 kW) at 4000 rpm and 310 lb·ft (420 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1965–1967 Ford F-Series

- 8.9:1 — 220 horsepower (160 kW) at 4400 rpm and 370 lb·ft (502 N·m) at 2400 rpm

- 1961–1963 Ford

- 1961–1963 Mercury (1961 Meteor and 1961–1963 Monterey, Commuter Wagon, Colony Park)

- 8.4:1 — 208 horsepower (155 kW) at 4000 rpm and 310 lb·ft (420 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 4V

- 10.2:1 — 300 horsepower (220 kW) at 4600 rpm and 395 lb·ft (536 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1958 Ford Interceptor

- 1958–1959 Ford

- 1958–1959 Ford Thunderbird

- 9.6:1 — 300 horsepower (220 kW) at 4600 rpm and 380 lb·ft (515 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1960 Ford

- 1960 Edsel[24]

- 1960 Ford Thunderbird

- 10.6:1 — 360 horsepower (270 kW) at 6000 rpm and 380 lb·ft (515 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 1960 Ford

- 8.9:1 — 235 horsepower (175 kW) at 4400 rpm and 350 lb·ft (475 N·m) at 2400 rpm

- 1960 Ford

- 9.3:1 — 250 horsepower (190 kW) at 4400 rpm and 352 lb·ft (477 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1964–1966 Ford

- 10.2:1 — 300 horsepower (220 kW) at 4600 rpm and 395 lb·ft (536 N·m) at 2800 rpm

361 Edsel

Edsel 361 engines were assembled in Cleveland Ohio, and Dearborn Michigan. They were standard equipment in the 1958 Edsel Ranger, Pacer, Villager, Roundup and Bermuda.[22] The Edsel 361 was the very first FE block engine to be offered for sale in any market, having been introduced to the public in the U.S. on September 4, 1957, almost two months before any 1958 Fords were sold.[25] The 361 cid 4V FE engine was also sold on 1959 Edsels in the U.S. and Canada, and 1958 and 1959 Ford and Meteor brand automobiles in Canada in place of the 352 cid, which was not available with any Ford Motor Company of Canada brand until the 1960 model year. Edsel 361 engines were available to U.S. law enforcement agencies and state and municipal emergency services purchasing fleet Fords as the 1958 Ford "Police Power Pack."[26][27][28]

361 Edsel engine configurations and applications

- 4V

- 10.5:1 Compression Ratio

- 303 bhp (225.9 kW) @4600 rpm

- 400 lb·ft (542 N·m) Torque @2800 rpm

- 4.0469 inches (102.79 mm) x 3.5 inches (88.90 mm) Bore/Stroke

- 4-bbl Holley or Ford (Autolite) carburetor

- Pushrod overhead valve

- Angle-wedge machined combustion chamber

- Firing order: 1-5-4-2-6-3-7-8

- Cylinder numbering (front-to-rear): Right 1-2-3-4 Left 5-6-7-8

- 18 mm spark plugs, 0.034 in. gap

- 1958 Edsel Ranger, Pacer, Villager, Roundup and Bermuda, standard equipment (called "E400")

- 4V

- 9.6:1[19][29] or 10.0:1 Compression Ratio depending on source of information.[30][31]

- 303 bhp (225.9 kW) @4600 rpm

- 390 lb·ft (529 N·m) Torque @2800 rpm

- 4.0469 inches (102.79 mm) x 3.5 inches (88.90 mm) Bore/Stroke

- 4-bbl Ford (Autolite) carburetor

- Pushrod overhead valve

- Angle-wedge cast combustion chamber

- Firing order: 1-5-4-2-6-3-7-8

- Cylinder numbering (front-to-rear): Right 1-2-3-4 Left 5-6-7-8

- 18 mm spark plugs, 0.034 in. gap

- 1959 Edsel Corsair, Villager and Ranger, optional equipment (called "Super Express V8")

360 Truck

The 360, of 360.7 cu in (5.9 L) actual displacement, was introduced in 1968 and phased out at the end of the 1976-year run; it was used in the Ford F Series trucks and pickups. It has a bore of a 390 (4.05 inches (102.87 mm)) and used the 352's 3.5 inches (88.90 mm) rotating assembly. 360s were also constructed with heavy duty internal components for truck use. Use of a standard 352/390 cam for use in passenger cars along with carburetor and distributor adjustment allowed the 360 to give performance similar to that of the 352 and 390 car engines. Rated at 215 bhp (160.3 kW) at 4100 rpm and 375 lb·ft (508 N·m) of torque @2600 rpm (2-barrel carb, 1968). The 360 used the same block, heads and other parts as a 390, this makes them indistinguishable from each other unless the stroke is measured.

360 Truck engine configurations and applications

- 2V, 8.4:1

- 215 bhp (160.3 kW) at 4100 rpm and 375 lb·ft (508 N·m) at 2600 rpm

- 1968–1971 Trucks[32]

- 196 horsepower (146 kW) net at 4000 rpm and 327 lb·ft (443 N·m) at 2400 rpm

- 1972–1976 Trucks

- 215 bhp (160.3 kW) at 4100 rpm and 375 lb·ft (508 N·m) at 2600 rpm

390

The 390, with 390.06 cu in (6.4 L) true displacement, had a bore of 4.05 inches (102.87 mm) and stroke of 3.785 inches (96.14 mm). It was the most common FE engine in later applications, used in many Ford cars as the standard engine as well as in many trucks. It was a popular high-performance engine;[33] although not as powerful as the 427 and 428 models, it provided good performance, particularly in lighter-weight vehicles. The 390 cu in (6.4 L) 2v is rated at 265 bhp (197.6 kW) @ 4,100 rpm, while the 4v version was rated at 320 bhp (238.6 kW) @ 4,100 rpm in certain applications. Certain 1967 & 68 Mustangs had 390 4v engines rated at 335 horsepower (250 kW), as did some Fairlane GTs and S code Mercury Cougars. When the 390 was first offered for 1961 model there was a 375 horsepower (280 kW) High Performance version that featured an aluminum 4bbl intake manifold, cast iron "header" style exhaust manifolds, 10.5:1 compression ratio and a solid lifter valve train. Many of these cars came with an aluminum 3x2bbl intake manifold in the trunk that was meant to be installed by the dealer and raised the engine's output to 401 horsepower (299 kW).

390 engine configurations and applications

- 2V

- 8.9:1 — 250 horsepower (190 kW) at 4400 rpm and 378 lb·ft (512 N·m) at 2400 rpm

- 1963–1965 Mercury

- 9.4:1 — 266 horsepower (198 kW) at 4600 rpm and 378 lb·ft (512 N·m) at 2400 rpm

- 1964–1965 Mercury

- 9.5:1 — 275 horsepower (205 kW) at 4400 rpm and 401 lb·ft (544 N·m) at 2600 rpm

- 1966 Ford

- 1966 Ford Fairlane

- 1966 Mercury

- 1966 Mercury Comet

- 9.5:1 — 270 horsepower (200 kW) at 4400 rpm and 401 lb·ft (544 N·m) at 2600 rpm

- 1967 Ford

- 1967–1968 Ford Fairlane

- 1967 Mercury

- 1967 Mercury Comet

- 1968 Ford Mustang

- 1968 Mercury Cyclone GT

- 1968 Mercury Cougar GT

- 10.5:1 — 280 horsepower (210 kW) at 4600 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1968 Ford

- 1969 Mercury

- 9.5:1 — 265 horsepower (198 kW) at 4400 rpm and 401 lb·ft (544 N·m) at 2600 rpm

- 1968 Ford Fairlane

- 1968 Ford Torino

- 1968–1970 Ford

- 1968–1970 Mercury

- 8.6:1 — 255 horsepower (190 kW) at 4400 rpm and 376 lb·ft (510 N·m) at 2600 rpm

- 1968–1971 Trucks[34]

- 9:1 — 255 horsepower (190 kW) at 4400 rpm and 376 lb·ft (510 N·m) at 2600 rpm

- 1971 Ford, Mercury

- 8.2:1 — 201 horsepower (150 kW) net at 4000 rpm and376 lb·ft (510 N·m) at 2600 rpm

- 1972–1975 Trucks

- 8.9:1 — 250 horsepower (190 kW) at 4400 rpm and 378 lb·ft (512 N·m) at 2400 rpm

- 4V

- 10.6:1 — 375 horsepower (280 kW) at 6000 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 1961–1962 Ford

- 9.6:1 — 300 horsepower (220 kW) at 4600 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1961–1963 Ford

- 1961–1963 Ford Thunderbird

- 1963 Mercury

- 9.6:1 — 330 horsepower (250 kW) at 5000 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1961–1963 Ford Police Interceptor

- 1963 Mercury Police Interceptor

- 10.1:1 — 330 horsepower (250 kW) at 5000 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1964 Ford Police Interceptor

- 1964 Mercury Police Interceptor

- 11:1 — 300 horsepower (220 kW) at 4600 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1964–1965 Ford

- 1964–1965 Mercury

- 1964–1965 Ford Thunderbird

- 10.5:1 — 315 horsepower (235 kW) at 4600 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1966–1967 Ford

- 1966–1968 Ford Thunderbird

- 1968 Mercury

- 10.5:1 — 335 horsepower (250 kW) at 4600 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1967, 1969 Ford Mustang

- 1967, 1969 Ford Fairlane

- 1967, 1969 Mercury Cyclone GT

- 1967, 1969 Mercury Cougar GT

- 1969 Ford Torino

- 1969 Mercury Montego

- 10.5:1 — 325 horsepower (242 kW) at 4800 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 10.6:1 — 375 horsepower (280 kW) at 6000 rpm and 427 lb·ft (579 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 3x2V, 10.6:1

- 401 horsepower (299 kW) at 6000 rpm and 430 lb·ft (580 N·m) at 3500 rpm

- 1961–1962 Ford

- 340 horsepower (250 kW) at 6000 rpm and 430 lb·ft (580 N·m) at 3500 rpm

- 1962 Ford

- 1962–1963 Ford Thunderbird

- 401 horsepower (299 kW) at 6000 rpm and 430 lb·ft (580 N·m) at 3500 rpm

Generation 2

406

The 406 engine used a new 4.13-inch (104.90 mm) bore with the 390's 3.785-inch (96.14 mm) stroke, giving a displacement of 405.7 cu in (6.6 L), rounded up to "406" for the official designation. The larger bore required a new block casting design allowing for thicker walls, but otherwise was very similar to the 390 block.[35]

It was available for less than two years before it was replaced by the 427.

Testing of the 406, with its higher power levels, led to cross-bolted mains – that is, main bearing caps that were secured not only by bolts at each end coming up from beneath, but also by bolts coming in from the sides through the block. A custom fit spacer was used between the cap and the block face. This design prevented the main bearing caps from "walking" under extreme racing conditions, and can be found today in many of the most powerful and modern engines from many manufacturers.

406 engine configurations and applications

- 4V, 11.4:1 — 385 horsepower (287 kW) at 5800 rpm and 444 lb·ft (602 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 1962–1963 Ford

- 1963 Mercury

- 3x2V, 11.4:1 — 405 horsepower (302 kW) at 5800 rpm and 448 lb·ft (607 N·m) at 3500 rpm

- 1962 Ford

- 3x2V, 12.1:1 — 405 horsepower (302 kW) at 5800 rpm and 448 lb·ft (607 N·m) at 3500 rpm

- 1963 Ford, Mercury

410

The 410 engine, used in 1966 and 1967 Mercurys (see Ford MEL engine regarding 1958 senior series Edsels), used the same 4.05 inches (102.87 mm) bore as the 390 engine, but with the 428's 3.98 inches (101.09 mm) stroke, giving a 410.1 cu in (6.7 L) real displacement. The standard 428 crankshaft was used, which meant that the 410, like the 428, used external balancing. A compression ratio of 10.5:1 was standard.

410 engine configurations and applications

- 4V, 10.5:1 — 330 horsepower (250 kW) at 4600 rpm and 444 lb·ft (602 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1966–1967 Mercury

427

The 427 V8 was a race-only engine produced as both a top-oiler and side-oiler. Introduced in 1963, its true displacement was 425.98 cubic inches, but Ford called it the 427 because 7 liters (427 cu in) was the maximum displacement allowed by several racing organizations at the time. The stroke was the same as the 390 at 3.784 inches (96.11 mm), but the bore was increased to 4.2328 inches (107.51 mm). The block was made of cast iron with an especially thickened deck to withstand higher compression. The cylinders were cast using cloverleaf molds—the corners were thicker all down the wall of each cylinder. Many 427s used a steel crankshaft and all were balanced internally. Most 427s used solid valve lifters with the exception of the 1968 block which was drilled for use with hydraulic lifters. Space-saving tunnel-port heads with matching intakes were available, which routed pushrods through the intake's ports in brass tunnels. As an engine designed for racing it had many performance parts available both from the factory and the aftermarket.

Two different 427 blocks were produced, the top oiler and side oiler. The top oiler version was the earlier, and delivered oil to the cam and valvetrain first and the crank second. The side oiler, introduced in 1965, sent oil to the crank first and the cam and valvetrain second. This was similar to the oiling design from the earlier Y-block. The engine was available with low-riser, medium-riser, or high-riser heads, and either single or double four-barrel carburetors on an aluminum manifold matched to each head design. Ford never released an official power rating.

The 427 remains a popular engine among Ford enthusiasts.

FE 427 exhausts. Left to right: Factory Ford cast iron header, aftermarket header with crossover tubes, aftermarket Tri-Y design, Factory Ford design "bundle-of-snakes" for use in the GT40

FE 427 exhausts. Left to right: Factory Ford cast iron header, aftermarket header with crossover tubes, aftermarket Tri-Y design, Factory Ford design "bundle-of-snakes" for use in the GT40 FE 427 injection manifolds. Left to right: Algon (1 of 2 versions), Tecalmit-Jackson, Hilborn (converted to efi), Factory Ford design tunnelport crossram for use in the GT40

FE 427 injection manifolds. Left to right: Algon (1 of 2 versions), Tecalmit-Jackson, Hilborn (converted to efi), Factory Ford design tunnelport crossram for use in the GT40 Tunnelport intake showing the brass tubes for the pushrods to pass through

Tunnelport intake showing the brass tubes for the pushrods to pass through

427 SOHC "Cammer"

The Ford single overhead cam (SOHC) 427 V8 engine, familiarly known as the "Cammer",[36] was released in 1964 in an effort to maintain NASCAR dominance by seeking to counter the enormously large block Chrysler 426 Hemi "elephant" engine. The Ford 427 block was closer dimensionally to the smaller 392 cu. in. first generation Chrysler FirePower Hemi; the Ford FE's bore spacing was 4.63 in (117.6 mm) compared to the Chrysler 392's 4.5625 in (115.9 mm). The Ford FE's deck height of 10.17 in (258.3 mm) was lower than that of the Chrysler 392 at 10.87 in (276.1 mm). For comparison, the 426 Hemi has a deck height of 10.72 in (272.3 mm) and bore spacing of 4.8 in (121.9 mm); both Chrysler Hemis have decks more than 0.5 in (12.7 mm) taller than the FE.

The engine was based on the high performance 427 side-oiler block, providing race-proven durability. The block and associated parts were largely unchanged, but an idler shaft replaced the camshaft in the block, which necessitated plugging the remaining camshaft bearing oiling holes.

The cast-iron heads were designed with hemispherical combustion chambers and a single overhead camshaft over each head, operating shaft-mounted roller rocker arms. The valvetrain consisted of valves larger than those on Ford wedge head engines, made out of stainless steel and with sodium-filled exhaust valves to prevent the valve heads from burning, and dual valve springs. This design allowed for high volumetric efficiency at high engine speed.

The idler shaft in the block in place of the camshaft was driven by the timing chain and drove the distributor and oil pump in conventional fashion. An additional sprocket on this shaft drove a second "serpentine" timing chain, 6 ft (1.8 m) long, which drove both overhead camshafts. The length of this chain made precision timing of the camshafts an issue at high rpms.

The engine also had a dual-point distributor with a transistorized ignition amplifier system, running 12 amps of current through a high-output ignition coil.

The engines were essentially hand-built for racing, with combustion chambers fully machined to reduce variability. Nevertheless, Ford recommended blueprinting before use in racing applications. With a single four-barrel carburetor they weighed 680 lb (308 kg)[37] and were rated at 616 horsepower (459 kW) at 7,000 rpm & 515 lb·ft (698 N·m) of torque @ 3,800 rpm, with dual four-barrel carburetors 657 horsepower (490 kW) at 7,500 rpm & 575 lb·ft (780 N·m) of torque @ 4,200 rpm. Ford sold them via the parts counter, the single four-barrel model as part C6AE-6007-363S, the dual carburetor model as part C6AE-6007-359J for $2350.00 (as of October, 1968).

Ford's hopes to counter Chrysler were, however, cut short. Although enough 427 SOHCs were sold to have the design homologated, Chrysler protests succeeded in getting NASCAR to effectively legislate the engine out of competition.[38] It was the only engine ever banned from NASCAR,[38] scuttling the awaited 1965 SOHC versus Hemi competition at the Daytona 500 season opener. Nevertheless, the SOHC 427 found its niche in drag racing, powering many altered-wheelbase A/FX Mustangs,[36] and becoming the basis for a handful of supercharged Top Fuel dragsters, including those of Connie Kalitta, Pete Robinson, and Lou Baney (driven by Don "the Snake" Prudhomme). In 1967 Connie Kalitta's SOHC-powered "Bounty Hunter" slingshot dragster won Top Fuel honors at AHRA, NHRA and NASCAR winter meets, becoming the only "triple crown" winner in drag racing history.[39] It was also used in numerous nitro funny cars including those of Jack Chrisman, "Dyno" Don Nicholson, Eddie Schartman, Kenz & Leslie, and in numerous injected gasoline drag racing vehicles.

427 engine configurations and applications

- Low-riser intake, 4V

- 10.9:1 — 390 horsepower (290 kW) at 5600 rpm and 460 lb·ft (620 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1968 Mercury Cougar GT-E only (it was to be offered in the Ford Mustang, according to early press releases, but there are no records or verification of any factory 427 Mustangs). In the spring of 1968, the 428 Cobra Jet officially replaced the 427; however, leftover 427s were installed until late June of that year, when stocks were depleted.

- 11.6:1 — 410 horsepower (310 kW) at 5600 rpm and 476 lb·ft (645 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 1963–1964 Ford

- 1963–1964 Mercury

- 10.9:1 — 390 horsepower (290 kW) at 5600 rpm and 460 lb·ft (620 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- Low-riser intake, 2x4V

- 12:1 — 425 horsepower (317 kW) at 6000 rpm and 480 lb·ft (650 N·m) at 3700 rpm

- 1963 Ford, Mercury

- 11.6:1 — 425 horsepower (317 kW) at 6000 rpm and 480 lb·ft (650 N·m) at 3700 rpm

- 1964 Ford, Fairlane, Mercury

- 12:1 — 425 horsepower (317 kW) at 6000 rpm and 480 lb·ft (650 N·m) at 3700 rpm

- Mid-riser intake, 4V

- 11.6:1 — 410 horsepower (310 kW) at 5600 rpm and 476 lb·ft (645 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 1965–1967 Ford

- 1965–1967 Mercury

- 11.6:1 — 410 horsepower (310 kW) at 5600 rpm and 476 lb·ft (645 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- Mid-riser intake, 2x4V

- 11.6:1 — 425 horsepower (317 kW) at 6000 rpm and 480 lb·ft (650 N·m) at 3700 rpm

- 1965–1967 Ford

- 1965–1967 Mercury

- 11.6:1 — 425 horsepower (317 kW) at 6000 rpm and 480 lb·ft (650 N·m) at 3700 rpm

428

With its 4.235" bore size, the 427 block was expensive to manufacture as the slightest shifting of the casting cores could make a block casting unusable. Therefore, Ford combined attributes that had worked well in previous incarnations of the FE – a 3.985 inches (101.22 mm) stroke and a 4.135 inches (105.03 mm) bore – to create an easier-to-make engine with nearly identical displacement. The 428 cu in (7.0 L) engine used a cast nodular iron crankshaft and external balancer.

428 FE engines were fitted to Galaxies (badged simply as '7 Litre') and Thunderbirds in the 1966 and 1967 model years. It was also found in Mustangs, Mercury Cougars, some AC (Shelby) Cobras and various other Fords. This engine was also available as standard equipment in 1966 and 1967 in the Mercury S-55.[40]

428 engine configurations and applications

- 4V, 10.5:1

- 345 horsepower (257 kW) at 4600 rpm and 462 lb·ft (626 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1966–1967 Ford

- 1966–1967 Ford Thunderbird

- 1966–1967 Mercury

- 1967 S-55

- 360 horsepower (270 kW) at 5400 rpm and 459 lb·ft (622 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1966–1970 Ford Police Interceptor

- 1966–1970 Mercury Police Interceptor

- 340 horsepower (250 kW) at 4600 rpm and 462 lb·ft (626 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1968 Ford

- 1968 Mercury

- 360 horsepower (270 kW) at 5400 rpm and 420 lb·ft (570 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1968 Shelby Cobra GT500

- 345 horsepower (257 kW) at 4600 rpm and 462 lb·ft (626 N·m) at 2800 rpm

428 Cobra Jet

The 428 Cobra Jet was a performance version of the 428 FE. Launched in April 1968, it was built on a regular production line utilizing a variety of cylinder heads [41] combined with a 735 cfm Holley four-barrel carburetor. The Cobra Jet used heavier connecting rods with a 13/32 rod bolt and a nodular iron crankshaft casting #1UB. As was the case for all pre-1972 American engines, this engine's HP and Torque ratings were SAE Gross, and therefore don't reflect the "as installed" (SAE NET) outputs. While some sources suggest actual engine outputs of "410 HP," there is no detailed documentation attributing that output to and actual production line stock engine.

An abundance of historical road test data on actual production 428 CJ cars suggest peak output in the neighborhood of 275 SAE Net ("as installed") HP, using published trap speed and "as tested" weights, and Hale's trap speed formula. Period road tests revealed quarter mile performance in the very high high thirteen to lower 14 second range, with trap speeds in the 101 to 103 MPH range: [42]

Chassis dynamometer information from well documented stock examples reinforces that estimate.[43] Similarly, this level of acceleration performance is on par with that of a production line stock, 2013+ V6/ speed manual transmission Accord (278 SAE Net HP), which shares a similar curb weight. It should be noted that a Holman and Moody specially prepared "stripper", which carried no sound deadener, undercoating, or any optional factory equipment, was used as the introductory press car in 1968.[44]

The 428 Cobra Jet engine (modified to the NHRA "stock" and "super stock" technical specs) made its drag racing debut at the eighth annual National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) Winternationals held from February 2–4, 1968, at the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds in Pomona, California. Ford Motor Company sponsored five drivers (Gas Ronda, Jerry Harvey, Hubert Platt, Don Nicholson, and Al Joniec) to race six 428 CJ-equipped Mustangs. The Mustangs raced in the C Stock Automatic (C/SA, 9.00 - 9.49 lbs. per advertised horsepower), Super Stock E, and Super Stock E Automatic (SS/E manual transmission, SS/EA automatic transmission, 8.70 - 9.47 lbs per factored horsepower) classes. The engine lived up to expectations as four of the cars made it to their respective class finals. Al Joniec won both his class (defeating Hubert Platt in an all-CJ final) and the overall Super Stock Eliminator (defeating Dave Wren) title.[45]

428 Cobra-Jet engine configurations and applications

- 4V, 10.5:1

- 345 horsepower (257 kW) at 4600 rpm and 462 lb·ft (626 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1966–1967 Ford

- 1966–1967 Ford Thunderbird

- 1966–1967 Mercury

- 1967 S-55

- 360 horsepower (270 kW) at 5400 rpm and 459 lb·ft (622 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1966–1970 Ford Police Interceptor

- 1966–1970 Mercury Police Interceptor

- 340 horsepower (250 kW) at 4600 rpm and 462 lb·ft (626 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- 1968 Ford

- 1968 Mercury

- 360 horsepower (270 kW) at 5400 rpm and 420 lb·ft (570 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1968 Shelby Cobra GT500

- 345 horsepower (257 kW) at 4600 rpm and 462 lb·ft (626 N·m) at 2800 rpm

- Cobra-Jet 4V, 10.8:1 — 335 horsepower (250 kW) at 5200 rpm and 440 lb·ft (600 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 1968 Ford Mustang

- 1968 Mercury Cougar

- 1968 Shelby GT500KR

- Cobra-Jet and Super Cobra-Jet 4V, 10.6:1 — 335 horsepower (250 kW) at 5200 rpm and 440 lb·ft (600 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 1969–1970 Ford Mustang

- 1969–1970 Mercury Cougar

- 1969 Ford Fairlane

- 1969 Ford Torino

- 1969 Mercury Cyclone

- 2x4V, 10.5:1 — 355 horsepower (265 kW) at 5400 rpm and 420 lb·ft (570 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1967 Shelby GT500

428 Super Cobra Jet

The 428 Super Cobra Jet (also known as the 428SCJ) used the same top end, pistons, cylinder heads, camshaft, valve train, induction system, exhaust manifolds, and engine block as the 428 Cobra Jet. However, the crankshaft and connecting rods were strengthened and associated balancing altered for drag racing. A nodular iron crankshaft casting #1UA was used as well as heavier 427 "Le Mans" connecting rods with capscrews instead of bolts for greater durability. The heavier connecting rods and the removal of the centre counterweight on the stock 428 Cobra Jet crankshaft (1UA), required an external weight on the snout of the crankshaft for balancing. A 428 Super Cobra Jet engine with oil cooler was standard equipment when the "Drag Pack" option (which came when selecting either a 3.91 or 4.30 rear end gear ratio) was ordered with cars manufactured from 13 November 1968. In addition, while the CJ and SCJ engines used the same autothermic piston casting, the piston-to-bore clearance specification between the CJ and SCJ 428 engines is slightly different, with the SCJ engines gaining a slightly looser fit to permit higher operating temperature.[46] Horsepower measurements at a street rpm level remained the same.[47] The 428 Super Cobra Jet engine was never offered with factory air conditioning due to the location of its engine oil cooler.

428 Cobra-Jet and Super Cobra-Jet engine configurations and applications

- Cobra-Jet and Super Cobra-Jet 4V, 10.6:1 — 335 horsepower (250 kW) at 5200 rpm and 440 lb·ft (600 N·m) at 3400 rpm

- 1969–1970 Ford Mustang

- 1969–1970 Mercury Cougar

- 1969 Ford Fairlane

- 1969 Ford Torino

- 1969 Mercury Cyclone

- 2x4V, 10.5:1 — 355 horsepower (265 kW) at 5400 rpm and 420 lb·ft (570 N·m) at 3200 rpm

- 1967 Shelby GT500

Vehicles

Selection of vehicles in which the FE was installed as original equipment:

1965 Ford Galaxie

1965 Ford Galaxie 1960 Ford Galaxie Starliner

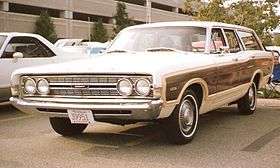

1960 Ford Galaxie Starliner 1968 Ford Torino Squire

1968 Ford Torino Squire 1965 Ford F100 Pick Up

1965 Ford F100 Pick Up 1967 Ford Fairlane Ranchero

1967 Ford Fairlane Ranchero- 1968 GTCS

1965 Thunderbird

1965 Thunderbird.jpg) 1963 Ford Galaxie 500 Convertible

1963 Ford Galaxie 500 Convertible.jpg) 1959 Ford Galaxie (Auto classique Laval '10)

1959 Ford Galaxie (Auto classique Laval '10)

Replacement

By the mid-1970s the FE had been used in Ford vehicles extensively across three decades. To replace it, Ford had developed the 335-series engines, commonly referred to as "Cleveland" engines, and the 385-series engines. These were produced in displacements ranging from 351 cu in (5.8 L) up to 460 cu in (7.5 L), including 429 cu in (7.0 L), giving Ford V8s of 427 cu in (7.0 L), 428 cu in (7.0 L), and 429 cu in (7.0 L). The last FE was installed in a production vehicle in 1976, and in the late 1970s the Dearborn Engine Plant that produced the FE engines was completely retooled to produce the 1.6 L engine introduced in the Ford Escort in 1981.

The FE's thinwall casting production method was innovative and forward-looking in the mid-1950, resulting in lower weight and dramatically reduced production costs. Ford's competitors at the time required thicker castings to mask the flaws and defects that resulted from their processes. Improving quality and allowing thinner walls was accomplished through many engineering improvements, including reducing the number of cores required to cast an engine block. Fewer cores made it easier to assemble the overall mold for casting and reduced the number of potential problems.[48] In the late 1980s when both Ford and GM revamped their V8 offerings, many of the FE's designs and engineering were incorporated in the new engines, including the deep skirt, cross-bolting of the mains and thinwall casting.

Ongoing enthusiast interest in the FE engine supports the continued availability of parts and engine kits needed to build or rebuild versions of the FE, notably the 427.

427-derived 2010 "Boss"

In 2010, after spending billions of dollars for engineering and tooling, Ford introduced a completely new and redesigned engine for use in its trucks. Referred to internally as the Hurricane during development, it is now being marketed as Boss. Using the same valvetrain geometry of the 427 SOHC, its cams were based on the older engine's design, modifying the ramps and creating a wasp-shaped lobe to help the rocker arms maintain contact with the cam at all engine speeds.[49]

The engine initially displaced 379 cu in (6.2 L), though the potential for larger displacements was engineered into the design. It had SOHCs actuating the valves via roller-tipped rockers mounted on rockershafts flanking the centrally located camshaft. Just like the FE Cammer, this allows splayed valves. It has a bore spacing of 4.53 inches, a stroke of 3.74 inches, a bore of 4.015 inches, and a deep-skirted thinwall casting block with cross-bolted mains.[50] The 1950s-designed 390 FE had a bore spacing of 4.63 inches, a stroke of 3.78 inches, a bore of 4.05 inches, and a deep-skirted thinwall casting block. The SOHC version of the FE with cross-bolted maincaps, developed in 1965, had single overhead cams actuating the valves via roller-tipped rockers. A 427 cu in (7.0 L) version of the new Boss engine was put together and tested. It produced 700 hp.[51]

Notes

- ↑ Disclaimer about the 1964 Thunderbolt modifications for drag racing: "This vehicle has been built specifically as a lightweight competitive car and includes certain fiberglass and aluminum components. Because of the specialized purpose for which this car has been built and in order to achieve maximum weight reduction, normal quality standards of the Ford Motor Company in terms of exterior panel fit and surface appearance are not met on this vehicle."

"This information is included on this vehicle to assure that all customers who purchase this care are aware of the deviation from the regular high appearance quality standards of the Ford Motor Company."[9][10]

References

- ↑ David W. Temple (2010). "Full-Size Fords: 1955-1970". Car Tech, Inc. p. 32.

- ↑ Christ, Steve (1983). How To Rebuild Big Block Ford Engines. HP Books, a division of Price Stern Sloan, Inc., 11150 Olympic Blvd., sixth floor, Los Angeles, CA 90064.

- ↑ Darryl Young (2011). "The Element of Surprise: Navy SEALS in Vietnam". Random House.

- ↑ "NASCAR Engines".

- ↑ Redgap, Curtis (2003). "Which came first? The Plymouth or the Petty?". allpar.com.

- ↑ "1966 Shelby Cobra 427 S/C". Supercars.net. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ Morris, Charlie. "Ford's 1965 Factory Experimental Mustangs", Car Tech Inc. website, undated article. Retrieved on August 26, 2008.

- ↑ Dennis Kolodziej. (Ford) Thunderbolt Details. Fordfe.com. 2011-04-15.Accessed: 2011-04-15. (Archived by WebCite at https://www.webcitation.org/5xyZfTxag)

- 1 2 "Reprint of January 2000 article in ''Hot Rod'' Magazine describing the disclaimer plate on a Thunderbolt used on a road tour". Hotrod.com. 2000-01-01. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- 1 2 "History of the lightweight 1964 Ford drag cars at". 1964ford.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "History of the Thunderbolt at". Musclecarclub.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ The Summit Racing Web Development Team. (2013-10-21). "FALL CLASSIC NO - Super Stock Qualifying, Sunday Final Order". Dragracecentral.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "Tony Densham & Commuter British L S R 1970". Archived from the original on February 17, 2012.

- ↑ "Bat Car Wows 'Em at Lions". Drag Digest, Volume 2 No. 18. May 19, 1967.

- ↑ Jeremy Kozniewski (2013-01-19). "1968 shelby exp 500 the green hornet". autoblog.com. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- ↑ "1970 Plymouth Hemi 'cuda Vs. 1969 Chevrolet Camaro ZL-1 Vs. 1968 Shelby "Green Hornet" Prototype - Muscle Car Comparison - Motor Trend Classic Page 4". Motortrend.com. 2006-06-12. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Hemmings.com. "EXP 500 | Hemmings Motor News". Hemmings.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Eric Geisert. Meguiars\'s 59th Annual Detroit Autorama. Street Rodder Magazine, page 53. Accessed: 2011-07-10. (Archived by WebCite at https://www.webcitation.org/604hmaQ2f)

- 1 2 3 1959 Edsel Data, Official Reference for Edsel Salesmen (A.K.A. 1959 Edsel Salesmen's Data Book). Ford Motor Company. 1958. p. D–1.

- 1 2 1958 Ford Fairlane and Fairlane 500 (sales brochure). Ford Motor Company. 1957. p. 6.

- 1 2 The 1959 Fords, the World's Most Beautifully Proportioned cars(sales brochure). Ford Motor Company. 1958. p. 16.

- 1 2 1958 Edsel Data, Official Reference Manual for Edsel Salesmen (A.K.A. 1958 Edsel Salesmen's Data Book). Ford Motor Company. 1957. p. F–3.

- ↑ New Ford Interceptor V-8 Engines. Ford. 1957.

- ↑ 1960 Edsel (A.K.A. Owner's Manual), form ED-5702-60. Ford. September 1959. p. 33.

- ↑ Warnock, C. Gayle (1980). The Edsel Affair. Pro West, Paradise Valley, Arizona 85253. p. 171.

- ↑ Christ, Steve (1983). How To Rebuild Big Block Ford Engines. HP Books, a division of Price Stern Sloan, Inc., 11150 Olympic Blvd., sixth floor, Los Angeles, CA 90064. p. 49.

- ↑ 1949–1959 Ford Car Parts and Accessories Illustrations Catalog, Form number FD 9463. Parts And Accessories Operations, Ford Division, Ford Motor Company. 1964. p. IX.

- ↑ 1949–1959 Ford Car Parts and Accessories Text Catalog, Form number FD 9462. Parts And Accessories Operations, Ford Division, Ford Motor Company. 1964. p. XI.

- ↑ Edsel for 1959, Owner's Manual, first edition, Form ED-5702-59. Ford Motor Company. September 1958. p. 57.

- ↑ Edsel for 1959, Owner's Manual, final edition, Form ED-5702-59. Ford Motor Company. December 1958. p. 49.

- ↑ Votre Edsel 1959, Owner's Manual, French Canadian edition. Ford Motor Company of Canada. December 1958. p. 60.

- ↑ Verified from 1971 Ford Truck Shop Manual First Print date November 1970 Volume 2 Engine pg 21-23-31 Sec. 9 Specifications General Specifications

- ↑ Clarke, R.M. (1992). Musclecar & Hi-Po Engines: Ford Big Block. Brooklands Books. p. 11. ISBN 1-85520-106-2.

- ↑ ~~~~, Verified from 1971 Ford Truck Shop Manual First Print date November 1970 Volume 2 Engine pg 21-23-31 Sec. 9 Specifications General Specifications

- ↑ Clarke, p. 11

- 1 2 Scale Auto, 6/06, p.15 sidebar.

- ↑ Clarke, p. 42 et seq.

- 1 2 http://autoweek.com/article/car-life/don-snake-prudhomme-brings-back-shelby-super-snake

- ↑ Steve Magnante|Inside the Swamp Rat's Nest|Street Rodder Premium Magazine|page 52|Volume 2 Number 2 Winter, 2011

- ↑ "Mercury 1966 move ahead with Mercury in the Lincoln Continental tradition" - Complete Model Line Description Brochure (1st ed.). Ford Motor Company, Dearborn MI. June 15, 1965. pp. 1–33.

- ↑ https://www.428cobrajet.org/id-heads

- ↑ http://wildaboutcarsonline.com/members/AardvarkPublisherAttachments/9990494729848/1969-02_SS_1969_Mustang_Mach_1_428_CJ_Test_1-4.pdf

- ↑ http://www.mustangandfords.com/how-to/engine/5216-8-mustang-musclecars-dynojet

- ↑ http://www.mustangandfords.com/featured-vehicles/mdmp-0707-fastest-mustang-tests

- ↑ "428 CJ Mustangs at the 1968 NHRA Winternationals | Mustang 428 Cobra Jet Registry". 428cobrajet.org. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "Pistons | Mustang 428 Cobra Jet Registry". 428cobrajet.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ "428 Cobra Jet vs. 428 Super Cobra Jet | Mustang 428 Cobra Jet Registry". 428cobrajet.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Huntington ASAE, Roger (January 1962). An Engineer Analyzes the 62s. Popular Mechanics Magazine. pp. 109–113, 238–242.

- ↑ Jay Brown. "Ford 427 Cammer Build". Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- ↑ The Ford Motor Company (2010-02-25). "Ford Motor Company. "Robust, Ford Tough: All-New 6.2-Liter Gasoline Engine Complements 2011 Ford Super Duty." Ford Media. 24 September 2009". Media.ford.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ ""Ford's Experimental Racing Engine" July". Hotrod.com. 2007-10-01. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

Further reading

- Peter C Sessler (1999). Ultimate American V8 Engine Data Book. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7603-0489-0.

- Steve Christ (1983). How to Rebuild Big-Block Ford Engines. New York: Berkeley Publishing Group. ISBN 0-89586-070-8.

External links

| Ford Motor Company engine timeline, North American market, 1950s–1970s — Next » | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 4-cylinder engines | Ford Pinto engine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I6 engines | Flathead I6 | Thriftpower I6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mileage Maker I6 | Truck I6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| V6 engines | Cologne V6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Small block V8 | Flathead V8 | 351 Cleveland V8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Windsor V8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ford Y-block V8 | 335/Modified V8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medium block V8 | FE V8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Big block V8 | Lincoln Y-block V8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MEL V8 | 385 V8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Super Duty V8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||