Folco de Baroncelli-Javon

| Folco de Baroncelli-Javon | |

|---|---|

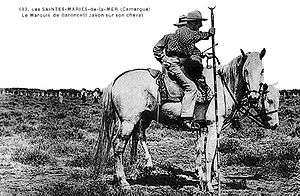

|

Baroncelli in full gardian attire | |

| Born |

1 November 1869 Aix-en-Provence |

| Died |

15 December 1943 (aged 74) Avignon |

| Occupation | writer, cattle breeder, cultural activist |

| Nationality | French |

| Period | early 20th century |

| Literary movement | Félibrige |

| Relatives | Jacques de Baroncelli (brother); Georges Dufrénoy (brother-in-law) |

Folco de Baroncelli-Javon (1 November 1869 – 15 December 1943), was a French writer and cattle farmer. As an influential gardian (a kind of Provençal cowboy), he is an important figure in the traditional lifestyle and culture of the Camargue region of southern France.

Family and childhood

Though born in Aix-en-Provence, Falco de Baroncelli-Javon was baptised in Avignon, where his parents lived. He came from a Florentine family who had settled in Provence in the 15th century, occupying a building in the centre of Avignon then called the Baroncelli Palace (now the Palais du Roure). His father's side of the family were of Tuscan origin and part of the Ghibelline tradition, and they were hereditary Marquises of Javon. Though somewhat aristocratic, the family spoke Provençal, which was rather controversial at a time when it was considered to be a language of the common people.

His brother was Jacques de Baroncelli, later a famous film director, and his sister, Marguerite de Baroncelli-Javon, later became ‘queen’ of the Occitan cultural movement known as the Félibrige, and married the post-impressionist painter Georges Dufrénoy.

Life in the Camargue

In 1895, lou Marquès (‘the Marquis’), as he was then known, moved to the Camargue and raised a herd of cattle called the Manado sentanco (the ‘holy herd’) in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer. He married the daughter of a Châteauneuf-du-Pape landowner, and had three daughters, but his wife did not take to the climate of the Camargue and their life together was patchy. Nevertheless, he settled in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer and became a tenant of a mas, or traditional ranch, called the Mas de l'Amarée.

In 1905, when an American rodeo show visited Nîmes, he met Joe Hammam and then Buffalo Bill. Becoming friendly, he offered the services of his gardians, who took part in Buffalo Bill's cowboys-and-Indians displays.

In May 1908, he met Jeanne de Flandreysy and fell in love. Their affair was short, but their friendship would remain an important part of Baroncelli's life. After the war, it was she who encouraged him to start writing, and he became an important part of the resurgent Occitan literary movement associated with Frédéric Mistral. Baroncelli was deeply affected by the carnage of the First World War, and became a fervent anti-militarist, later supporting a local Communist mayor.

Most importantly, perhaps, he played an active role in maintaining and fostering a native Camarguais culture. He was involved in codifying the nascent ‘course camarguaise’, or local style of bullfighting, in which the object was to snatch a rose from the bull's head. He put a lot of effort into raising purebred Camargue bulls, and his bull Prouvenço was a particularly fiercesome and well-known example.

In 1909 he founded the Nacioun Gardiano (‘gardian nation’) to preserve the traditions of the Camargue.[1]

In 1931, out of money, Baroncelli had to leave the Mas de l’Amarée. Locals offered him a patch of land nearby where he constructed a replica of his old ranch, calling it the Mas du Simbèu (‘sign, emblem’; also the name given to the chief bull of a herd). Among other things, he became an important supporter of the Romany people in this area, and counted many gypsies among his close friends.

The late 1930s were marked by a series of illnesses, and the outbreak of the Second World War would prove too disruptive for him. His ranch was requisitioned by German troops in 1943, and the Marquis was evicted to Saintes-Maries. Sick and disoriented, he finally died at Avignon in December 1943.

Legacy

The image which many in France have of the Camargue is essentially of the traditions and customs which Baroncelli worked for his whole life. As a working gardian, he was intimately involved with the Camargue horses and Camargue bulls which are emblematic of the region. And he also left an important body of writing describing the area, including Camarguais folktales published in the local dialect of Occitan. His writing and his work helped to give the area a sense of individual importance which it has maintained to this day.

Further reading

- Sully-André Peyre (1955). Folco de Baroncelli, poète provençal. Aigues-Vives: Marsyas. OCLC 743062902.

- Henriette Dibon (1982). Folco de Baroncelli. Nimes: Bene. OCLC 13014257.

- Folco de Baroncelli-Javon; Jeanne de Flandreysy (2013). Le crépuscule du marquis, 1942-1943 : Folco de Baroncelli et Jeanne de Flandreysy, une année de correspondance. Avignon: Palais du Roure. ISBN 9782954692111. OCLC 887508462.

References

- ↑ Roche, Alphonse V. (Spring 1954). "Modern Provençal Literature". Books Abroad. 28 (2): 171–174. JSTOR 40092939. doi:10.2307/40092939. (Registration required (help)).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Folco de Baroncelli-Javon. |