Florine Stettheimer

| Florine Stettheimer | |

|---|---|

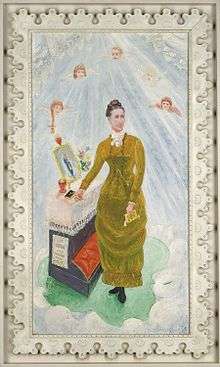

Florine Stettheimer, American artist, in her Bryant Park garden c.1917–1920. Image held in the collection of the Florine Stettheimer papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. | |

| Born |

August 29, 1871 Rochester, New York |

| Died | May 11, 1944 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | painter |

Florine Stettheimer (August 29, 1871 – May 11, 1944) was an American painter, designer, Jazz Age saloniste[1] and poet.

With her sisters, Carrie and Ettie, she hosted a salon for modernists in Manhattan, which included Marcel Duchamp, Henry McBride, Carl Van Vechten and Georgia O'Keeffe. She confined most exhibitions of her own work to these gatherings, occasionally submitting work to the Society of Independent Artists. Florine shared original poems at her salons, and a book of her work, Crystal Flowers, was published privately and posthumously by her sister Ettie Stettheimer in 1949. It was reissued to acclaim in 2010.[2]

Early life

Florine was born in Rochester, New York to Rosetta Walter and Joseph Stettheimer, a family of wealthy German-Jewish ancestry.[3] Her father, a banker, left the family before the children were grown. She was the fourth of five children: Walter, Stella, Carrie, Florine, and Ettie. After Walter and Stella married, the three youngest children were raised in a close relationship with their mother, who adopted an epicurean way of life.[4] The three sisters were known as the "Stetties" and lived a life of leisure oriented on artistic pleasure and work. From 1906 to 1914, Florine lived abroad with her fellow "Stetties" and mother while continuing to enhance her education of the arts in Berlin, Stuttgart and Munich. [5]

Career

Painter and salonière

Stettheimer studied for three years 1892 to 1895 at the Art Students League of New York,[6] but came into her own artistically upon her permanent return to New York after the start of World War I. From 1915 to 1935, she and her sisters Ettie and Carrie hosted a salon "for the contemporary literati, gay and polyglot New Yorkers and European expatriates".[7][8]

Stettheimer preferred to restrict showing her work to a more private audience as opposed to exhibiting publicly. In October 1916, the only solo exhibition of her work during her lifetime took place at Knoedler & Company in Manhattan, curated by Marie Sterner.[9] She exhibited twelve "high-keyed, decorative paintings", none of which were sold.[10]

From then on, Stettheimer preferred to show her work "in non-competitive situations", as Barbara Bloemink writes.[11] Thus year after year, over a period of two decades, Stettheimer entered her work at the Annual exhibitions of the Society of Independent Artists. She also continued to refine her style in rendering highly personal self-portraits, including a self-portrait in the nude, and group portraits that included her own family. Other works, such as her 1920 painting Asbury Park South, depict parties or gatherings held with her friends and family.[12] She also prepared a number of well known portraits of Marcel Duchamp that explore androgyny and doubling. Cushioned by family resources, Stettheimer refrained from self-promotion and considered her painting "an entirely private pursuit". She intended to have her works destroyed after her death, a wish defied by her sister Ettie, her executor.[13]

Stettheimer's privileged position pervades her work. As one critic has written,

...money she regarded as a birthright, decidedly not something to be flaunted in the shape of a dozen yachts, but rather to be used as a palliative against the more unpleasant aspects of the world outside... In this frame of mind, she felt free to depict life as a series of boating parties, picnics, summertime naps, parades and strolls down Fifth Avenue.[14]

Set designer

Stettheimer created the sets and costumes for the 1934 production of Four Saints in Three Acts, an opera by Virgil Thomson that included a libretto by Gertrude Stein. Her designs, which used cellophane in innovative ways, proved to be the project for which she was best known during her lifetime.[15]

Stettheimer also exhibited her flair for the stage and performance by composing the libretto for “Orphée of the Quat-z-arts or the Revellers of the 4 Arts Ball”, a ballet inspired by the annual ball organized by the four artists’ guilds in Paris. The ballet was never staged, but Stettheimer’s libretto was first published in its entirety in the 2010 reissue of Crystal Flowers. Irene Gammel and Suzanne Zelazo, in their introduction to that volume, describe the ballet: “[Its] central character Georgette (a modern-day Euridice) navigates social strata, merging bohemian carnivalesque with the charms of ‘a blonde Vicomte’”.[16]

Stettheimer assisted her sister Carrie in the creation of the Stettheimer Dollhouse, now in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York. The house is a whimsical depiction of an upper-class residence, filled with works by Stettheimer's artist friends, including William Zorach, Alexander Archipenko, Marcel Duchamp, and Gaston Lachaise.[17]

Poet

Stettheimer wrote her poems on little scraps of paper and, like Emily Dickinson, sent them to friends instead of publishing them. Some of her poems are written in nursery style, some offer witty social critiques, and others present brilliantly satiric portraits of fellow modernists, such as Gertrude Stein ("Gertie") and Marcel Duchamp ("Duche"). Her poems show an awareness of contemporary consumer culture and offer an acerbic indictment of marriage, as her poem dedicated to Marie Sterner, "who intended to be a musician/ but Albert married her."[18] Stettheimer’s poems were posthumously assembled in Crystal Flowers, collected and edited by her sister Ettie and published in 1949. Light and diaphanous, these poems were reissued in 2010, with the editors arguing that "[in] her hands and on her tongue, the surface for Stettheimer is depth."[19]

Modernist sensibilities and contributions

As an American modernist of German-Jewish heritage, Stettheimer was able to cultivate a distinctive camp aesthetic and personal focus that have drawn the attention of twentieth- and twenty-first-century readers and viewers. In their essay, "Wrapped in Cellophane: Florine Stettheimer’s Visual Poetics", Irene Gammel and Suzanne Zelazo review the various positions voiced by scholars and biographers regarding Stettheimer’s unique modernist sensibility, whose whimsy seems very different from mainstream modernists. They write:

Unapologetically domestic and über-feminine, Stettheimer’s work has been variously described as ‘faux naïf,’ reveling in simplified shapes and Fauve-like colors (Tatham); as ‘rococo subversive,’ embracing a camp sensibility (Nochlin); and as ‘temporal modernism’ influenced by Bergsonian concepts of time as heterogeneous durée, aligning Stettheimer with Marcel Proust and other literary modernists (Bloemink).[20]

Representing a modernism that integrates various art forms, Stettheimer’s paintings, like her poems, were sensory and sensually charged. Thus "a close look at the poems reveals equally glittering surfaces and glossy protective veneers" that may be found in the paintings. Gammel and Zelazo locate in Stettheimer’s work a "grammar of artifice ... designed to cultivate an acute awareness of aesthetic perspective in the reader", as well as "an aesthetics of cellophane", a decidedly modern material she used to decorate her stages and her bedroom, occasionally mixing it with old-fashioned laces.[21] Drawing deliberate attention to the transparent surface, her work has a depth that belies a first glance.

Death

Stettheimer died of cancer in 1944 at the age of seventy-two.

Legacy

After the deaths of her sisters, 45 works were given to 37 institutions, with another 50 going to Columbia University in 1967 in anticipation of a new arts center which was never built.[22]

Stettheimer has been the subject of posthumous retrospectives at institutions including the Museum of Modern Art (in 1946) and the Whitney Museum of American Art (in 1995). Up until the point in which her art was shown in the Whitney Museum of American Art, her works were relatively un-known. Her death came right after WWII where the popular perspective seemed to be industrial and quite serious art. Stettheimer's pieces have been deemed to fit into the "Rococo Subversive" genre due to their subtle satire.[23] In 1980, as a successor to her 1946 retrospective at MOMA, the ICA Boston mounted the exhibition Florine Stettheimer: Still Lifes, Portraits, and Pageants, 1910–1943.[24]

Four of Stettheimer's paintings from the Cathedral series—the Cathedrals of Wall Street, Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and Art—all painted between 1929 and 1942 and structured around a central arch form are part of the permanent collection of the American Painting and Sculpture wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[25]

Florine Stettheimer's work is now being shown in New York City at The Jewish Museum in Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry, an exhibition that will continue until September 24, 2017.[26]

Further reading

Works

- Stettheimer, Florine, Crystal Flowers, edited by Irene Gammel and Suzanne Zelazo, BookThug, 2010.

Print biographies and monographs

- Florine Stettheimer /edited by Matthias Mühling, Karin Althaus, and Susanne Böller; translations: Gerrit Jackson. Munich: Lenbachhaus; Munich: Hirmer. 2014. ISBN 9783777422640.

- Bloemink, Barbara J. The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer. New Haven:Yale University Press, 1995.

- Brown, Stephen and Uhlyarik, Georgiana. Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry. New York, Toronto, New Haven and London: Jewish Museum, Art Gallery of Ontario, Yale University Press, 2017. With Jens Hoffmann in conversation with Cecily Brown, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Jutta Koether, Ella Kruglyanskaya, Valentina Lieurnur, Silke Otto-Knapp, Katharina Wulff.

- McBride, Henry. "Florine Stettheimer." New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1946.

- Tyler, Parker. Florine Stettheimer: A Life in Art. New York: Farrar, Straus, 1963.

- Watson, Steven. Prepare for Saints: Gertrude Stein, Virgil Thomson, and the Mainstreaming of American Modernism. New York: Random House, 1998.

Theses

- Liles, Melissa M., "Florine Stettheimer: A Re-Appraisal of the Artist in Context," Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University, 1994.

References

- ↑ A case for the greatness of Florine Stetteimer, NYTimes, May 19, 2017, Retrieved May 19, 2017

- ↑ Florine Stettheimer, Crystal Flowers: Poems and a Libretto. Ed. Irene Gammel and Suzanne Zelazo. Toronto: BookThug, 2010. See Holland Cotter, "For Art Lovers: Volumes Meant to Awe and Inspire," New York Times, November 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Florine Stettheimer: "Occasionally A Human Being Saw My Light"". Venetian Red Art Blog. 2009-07-01. Retrieved 2014-02-08.

- ↑ Tyler, Parker. "Stettheimer, Florine" Notable American Women. Vol. 3, 4th ed., The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1975

- ↑ Morgan, Barbara (2001). Women in World History : a Biographical Encyclopedia. Detroit [u.a.]: Gale Group. ISBN 0787640689.

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/565887/Florine-Stettheimer

- ↑ Gammel, Irene and Suzanne Zelazo. "Words as Painted Air: The Iridescence of Florine Stettheimer’s Poetry". Introduction to Stettheimer, Crystal Flowers, 19.

- ↑ "Extravagant Crowd | Stettheimer Sisters". brbl-archive.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ Bloemink, Barbara, The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. 76-78.

- ↑ Morgan, Lee Ann, "The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer", Art Journal, Summer 1996. Retrieved December 16, 2006

- ↑ Bloemink, 80.

- ↑ Laxton, Susan. "Florine Stettheimer". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Naves, Mario, "Florine Stettheimer: Manhattan Fantastica", The New Criterion, September 1995. Retrieved December 16, 2006

- ↑ Winkfield, Trevor, "Very Rich Hours - Artist Florine Stettheimer", Art in America, January 1996. Retrieved December 16, 2006

- ↑ Danforth, Ellen Zak, Florine and Ettie Stettheimer Papers, Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale Collection of American Literature, September 1987. Retrieved December 16, 2006

- ↑ Gammel and Zelazo, "Words as Painted Air", 25–27.

- ↑ Raynor, Vivien, "Art: A Rogues' Gallery of Artists and Esthetes, The New York Times, October 14, 1993. Requires registration; retrieved December 16, 2006

- ↑ Stettheimer, Crystal Flowers, 106.

- ↑ Gammel and Zelazo, "Words as Painted Air", 28.

- ↑ Gammel, Irene and Suzanne Zelazo. "Wrapped in Cellophane: Florine Stettheimer’s Visual Poetics". Woman’s Art Journal 32.2 (Fall/Winter 2011), 14.

- ↑ Gammel and Zelazo, "Wrapped in Cellophane", 25–27.

- ↑ Mulcahy, Susan, "Columbian Art: How a university bequest can go wrong", New York Magazine, March 14, 2005. Retrieved December 15, 2006

- ↑ Morgan.Barbara. "Women in World History: A Biographical Edition". Ed. Anne Commire. Vol. 14. Detroit: Yorkin Publications, 2002. 798–801.

- ↑ "History | icaboston.org". icaboston.org. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- ↑ Earnest, Jarrett (March 2012). "Florine Stettheimer: Hieroglyphs of Pleasure". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ↑ "Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry". The Jewish Museum. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

External links

- Florine Stettheimer Collection at Columbia University

- Works by or about Florine Stettheimer at Internet Archive

- Triple Canopy a short piece on Stettheimer's poetry

- Florine Stettheimer at The Jewish Museum