Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles

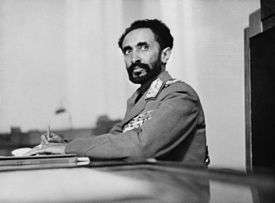

Until the end of the Ethiopian monarchy in 1974, there were two categories of nobility in Ethiopia. The Mesafint (Ge'ez: መሳፍንት? masāfint, modern mesāfint, singular Ge'ez: መስፍን ? masfin, modern mesfin, "prince"), the hereditary nobility, formed the upper echelon of the ruling class. The Mekwanint (Ge'ez: መኳንንት?mäkʷanin, modern mäkʷenin singular Ge'ez: መኳንንት? mäkʷanin, modern mäkʷenin or Amharic: መኮንን? mekonnen, "governor") were the appointed nobles, often of humble birth, who formed the bulk of the aristocracy. Until the 20th century, the most powerful people at court were generally members of the Mekwanint appointed by the monarch, while regionally, the Mesafint enjoyed greater influence and power. Emperor Haile Selassie greatly curtailed the power of the Mesafint to the benefit of the Mekwanint, who by then were essentially coterminous with the Ethiopian government.

The Mekwanint were officials who had been granted specific offices in the Abyssinian government or court. Higher ranks from the title of Ras through to Balambaras were also bestowed upon members of the Mekwanint. A member of the Mesafint, however, would traditionally be given precedence over a member of the Mekwanint of the same rank. For example, Ras Mengesha Yohannes, son of Emperor Yohannes IV and thus a member of the Mesafint, would have outranked Ras Alula Engida, who was of humble birth and therefore a member of the Mekwanint, even though their ranks were equal.

There were also parallel rules of precedence, primarily seniority based on age, on offices held, and on when they each obtained their titles, which made the rules for precedence rather complex. Combined with the ambiguous position of titled heirs of members of the Mekwanint, Emperor Haile Selassie, as part of his program of modernising reforms, and in line with his aims of centralising power away from the Mesafint replaced the traditional system of precedence with a simplified, Western-inspired system that gave precedence by rank, and then by seniority based when the title had been assumed – irrespective of how the title was acquired.[1]

Imperial and royal titles

Negusa Nagast

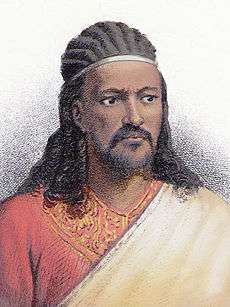

The Negusa Nagast (Ge'ez: ንጉሠ ነገሥት? nəgusä nägäst, "King of Kings") was the Emperor of Ethiopia. Although several kings of Aksum used this style, until the restoration of the Solomonic dynasty under Yekuno Amlak, rulers of Ethiopia generally used the style of Negus, although "King of Kings" was used as far back as Ezana.

The full title of the Emperor of Ethiopia was Negusa Nagast and Seyoume Igziabeher ("Elect of God"). The title Moa Anbessa Ze Imnegede Yehuda ("Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah") always preceded the titles of the Emperor. It was not a personal title but rather referred to the title of Jesus and placed the office of Christ ahead of the Emperor's name in an act of Imperial submission. Until the reign of Yohannes IV, the Emperor was also Neguse Tsion (Ge'ez: ንጉሠ ጽዮን?, nəgusä tsiyon), "King of Zion"), whose seat was at Axum, and which conferred hegemony over much of the north of the Empire.

The Emperor was referred to by the dignities of the formal Girmawi (Ge'ez: ግርማዊ?, gärimawi, "His Imperial Majesty"), in common speech as Janhoy (Ge'ez: ጃንሆይ? janihoy, "Your [Imperial] Majesty, or lit. "sire" ), in his own household and family as Getochu (our Master in the plural), and when referred to by name in the third person with the suffix of Atse (effectively "Emperor", i.e. Atse Menelik).

All formal speech concerning the Emperor was in the plural, as was his own speech; Haile Selassie, for instance, referred to himself in the first-person plural at all times, even in casual conversation and when speaking in French (however this was not the case when he spoke in English, in which he was not fully fluent).[2]

Negus

A Negus (Ge'ez: ንጉሥ? nəgus, "king") was a hereditary ruler of one of Ethiopia's larger provinces, over whom collectively the monarch ruled, thus justifying his imperial title. The title of Negus was awarded at the discretion of the Emperor to those who ruled important provinces, although it was often used hereditarily during and after the Zemene Mesafint. The rulers of Begemder, Shewa, Gojjam, Wollo, all held the title of Negus at some point, as the "Negus of Shewa", "Negus of Gojjam", and so forth.

During and after the reign of Menelik II virtually all of the titles either lapsed into the Imperial crown or were dissolved. In 1914, after having been appointed "Negus of Zion" by his son Lij Iyasu (Iyasu V), Mikael of Wollo, in consideration of the hostile feelings this provoked in of much of the nobility in northern Ethiopia (particularly Le'ul Ras Seyoum Mengesha, whose family had resented being denied the title by Menelik), who were now technically made subordinate to him, instead elected to use the title of Negus of Wollo. Tafari Makonnen, who later became Emperor Haile Selassie, was bestowed the title of Negus in 1928; he would be the last person to bear the title.[3]

Despite this, European sources referred to the Ethiopian monarch as the Negus well into the 20th century, switching to Emperor only after the Second World War- around the same time the name Abyssinia fell out of use in favour of Ethiopia in the west.

Le'ul

Le'ul (Ge'ez: ልዑል? lə‘ul, "Prince") was a princely style used by sons and grandson of the Emperor. It conferred upon its holder the title of Imperial Highness. The style first came into use in 1916, following the enthronement of Empress Zewditu.

Abeto

Abetohun (Ge'ez: አቤቶሁን? abētōhun) or Abeto (Ge'ez: አቤቶ? abētō) -- Prince. Title reserved for males of Imperial ancestry in the male line. Title fell into disuse by the late 19th century. Lij Iyasu attempted to revive the title as Abeto-hoy ("Great Prince"), and this form is still used by the current Iyasuist claimant Girma Yohannes Iyasu.

Ras

- Ras (Ge'ez: ? ራስ ras, lit. "head", compare with Arabic Rais) -- One of the powerful non-imperial; historian Harold G. Marcus equates this to a duke. The combined title of Leul Ras was given to the heads of the cadet branches of the Imperial dynasty, such as the Princes of Gojjam, Tigray and the Selalle sub-branch of the last reigning Shewan Branch.

Bitwoded

- Bitwoded (Ge'ez: ? ቢትወደድ bitwädäd, lit. "beloved") -- An office thought to have been created by Zara Yaqob who appointed two of these, one of the Left and one of the Right. These were later merged into one office, which became the supreme grade of Ras, "Ras Betwadad". Marcus equates the style to an earl.

Lij

- Lij (Ge'ez: ? ልጅ ləj, lit. "child") -- Title issued at birth to sons of members of the Mesafint, the hereditary nobility.

Men's military titles

- Dejazmach (ደጃዝማች däjazmač, "Commander or General of the Gate") -- a military title meaning commander of the central body of a traditional Ethiopian armed force composed of a vanguard, main body, left and right wings and a rear body.[4] Marcus equates this to a count. The heirs of the "Leul Rases" were titled Leul Dejazmach to elevate them above the non-Imperial blood Dejazmaches.

- Fit'awrari (ፊትአውራሪ fit’awrari, Commander of the Vanguard) -- a military title meaning commander of the vanguard of a traditional Ethiopian armed force. Marcus equates this to a baron.

- Grazmach (ግራዝማች grazmač, Commander of the Left wing) -- a military title meaning commander of the left wing of a traditional Ethiopian armed force.[4]

- Qenyazmach (ቀኛዝማች qəñazmač, Commander of the Right wing) -- a military title meaning commander of the right wing of a traditional Ethiopian armed force.[4]

- Azmach (አዝማች azmač, Commander of the Rearguard) -- a military title meaning commander of the rearguard of a traditional Ethiopian armed force. This was usually a trustworthy counselor and the leader's chief minister.[4]

- Balambaras (ባላምባራስ balambaras, Commander of an Amba or fortress) -- these could also be commanders of the guards, artillery or cavalry of a traditional Ethiopian armed force, basically a man entrusted with important commands.[4]

Women's honorifics

- Nigiste Negestatt - "Empress Regnant" (ንግሥተ ነገሥታት nígəstä nəgəstât) (in her own right) Literally "Queen of Kings," or "Queen of Queens," or "female ruler of an empire." Zewditu (reigned 1917–1930) was the only woman to be crowned in Ethiopia in her own right since ancient times. Rather than take the title Itege, which was reserved for empress consorts, Zewditu was given the feminized version of Nigusa Nigist to indicate that she reigned in her own right. She was accorded the dignity of Girmawit ("Imperial Majesty") and the title of Siyimta Igzi'abher (ሥይምተ እግዚአብሔር səyəmtä ’əgziabhēr, "Elect of God"). She was commonly referred to as Nigist "Queen". The 1955 Constitution of Ethiopia excluded women from the succession to the throne so this title was effectively abolished.

- Itege (እቴጌ ’ətēgē) "empress consort". Empresses were generally crowned as consorts by the emperor at the Imperial Palace. However, Taytu Betul, consort of Menelik II, became the first Itege to be crowned by the Emperor at church rather than at the Palace. Her coronation took place on the second day of the emperor's coronation holiday. Menen Asfaw became the first Itege to be crowned by the archbishop on the same day and during the same ceremony as her husband, Haile Selassie. The Itege was entitled to the dignity of Girmawit ("Her/Your Imperial Majesty").

- Le'elt (ልዕልት lə‘əlt) "Princess". Title came into use in 1916 upon the enthronement of Zewditu. Reserved at birth for daughters of the monarch and patrilineal granddaughters. Usually bestowed on the wives of "Leul Rases" as well as the monarch's granddaughters in the female line upon their marriages. The notable exception to the rule was Leult Yeshashework Yilma, Emperor Haile Selassie's niece by his elder brother, who received the title with the dignity of "Highness" from Zewditu upon the princess' marriage to Leul Ras Gugsa Araya Selassie in 1918, and then again from her uncle upon his coronation in 1930 with the enhanced dignity of "Imperial Highness".

- Emebet Hoy (እመቤት ሆይ ’əmäbēt hōy, "Great Royal Lady") --Reserved for the wives of those bearing the title of Leul Dejazmach and other high ranking women of Royal blood.

- Emebet (እመቤት, "Royal Lady" ’əmäbēt) --Reserved for the unmarried granddaughters of the monarch in the female line (they were generally granted the title of leult upon marriage), and to the daughters of the "Leul Rases".

- Woyzero (ወይዘሮ wäyzärō, Dame) -- Originally high noble title that over time came to be the general accepted form of address for married women in general (Mrs.). It was still awarded by the Emperor on rare occasions in the 20th century to non-royal women, and sometimes with the higher grade of Woizero Hoy (Great Dame).

- Woyzerit (ወይዘሪት wäyzärit, Lady) -- Originally high ranking noble title for unmarried women, now the general accepted form of address for unmarried women in general (Miss). It was sometimes awarded with the added distinction of Woizerit Hoy (Great Lady), but only to widows.

Important regional offices

- Bahr negus (ባህር ንጉሥ bahər nəgus, "ruler of the Seas") -- King of the territories north of the Mareb River, and as a result the most powerful office in medieval Ethiopia after the Emperor himself. As a result of the revolts of the Bahr negus Yeshaq and the self-determination of Medri Bahri in modern-day Eritrea in the later 16th century, this office lost much of its power. Although men are mentioned as holding this office into the early 18th century, they were of little consequence.

- Meridazmach (መርዕድ አዝማች märəd ’azmač, "Fearsome Commander" or "supreme general") -- This title is related to "Dejazmach" or "Kenyazmach" above. Beginning in the 18th century, this came to denote the ruler of Shewa until Sahle Selassie dropped it in favor of the title of Negus. Later revived in 1930 in Wollo for Crown Prince Asfaw Wossen.

- Mesfin Harar (መስፍነ ሐረር mäsfinä ḥarar) --Duke of Harar. Hereditary title created in 1930 for Emperor Haile Selassie's second son, Prince Makonnen. (The wife of the Mesfin was properly titled Sefanit, but was more commonly referred to as the Mesfinit). Upon the death of the Prince, his son Prince Wossen Seged was elevated as Mesfin Harar and would currently be second in line in the line of succession if Ethiopia were still a monarchy after Prince Zera Yacob.

- Nebura ed (ንቡረ እድ nəburä ’əd, one put in office through the laying of hands") -- civil governor of Axum reserved for the clergy. Also called Liqat Aksum. Because of the historical and symbolic importance of this city, the rules of precedence promulgated in 1689 ranked the Nebura ed ahead of all of the provincial governors. Indeed, when the title was granted with Ras Warq (the right to wear a coronet), it was higher than even the title of Ras. Although a civil title granted by the Emperor, it was usually bestowed on a clergyman due to Axum's status as the holiest site of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church within the country.[5] The title of Nebure ed was also granted to the administrator of the Church of St. Mary at Addis Alem, founded by Menelik II west of Addis Ababa. However the Nebura ed of Addis Alem was much further down the hierarchy than the Nebura ed of Axum, and was not accorded the Ras Warq.

- Tigray Mekonnen (ትግራይ መኮንን təgray mäkōnən) -- governor of the province of Tigray. Under the rule of Emperor Yohannes IV in the late 19th century, the Tigray Mekonnen briefly became responsible for the territories once controlled by the Bahrnegus, and became the most powerful governor of Eritrea.

- Wagshum (ዋግሹም wagšum) -- governor (or shum) of the province of Wag. The Wagshum was a hereditary title, and these rulers traced their ancestry back to the imperial family of the Zagwe dynasty.

- Shum Agame -- Governor of Agame district of Tigray, and hereditary in the family of Dejazmach Sebagadis, a major figure of the Zemene Mesafint (Era of the Princes) period. Ras Sebhat Aregawi, a longtime rival of the family of Emperor Yohannis IV was one of the more famous of the Shum Agame.

- Shum Tembien (ሹም ታምብየን šum tambyän) -- Governor of Tembien district of Tigray. Emperor Yohannes IV was the son of Shum Mercha of Tembien.

- Jantirar - Title reserved for the males of the family who ruled over the mountain fortress of Ambassel in Wollo (now Debub Wollo Zone). The title of Jantirar is among the oldest in the Ethiopian Empire. Empress Menen, consort of Emperor Haile Selassie, was the daughter of Jantirar Asfaw.

Important offices of the Imperial Court

Enderase

The Enderase (እንደራሴ ’əndärasē, lit. "as myself") acted as the Regent of the Empire in times of the Emperor's youth, infirmity, or other limited capacity. Empress Zauditu, who reigned from 1917 to 1930, was obliged to share power with an Enderase, Ras Tafari Makonnen, who was also her designated heir, and thus assumed the throne as Emperor Haile Selassie in 1930.

The title used by the monarch's representatives to fiefs and vassals (in this sense, a Viceroy). In the 20th century, the title was used by some provincial governors, chiefly that of the autonomous province of Eritrea, which had been restored to Ethiopia in 1952. The title was still used after the dissolution of the federal arrangement, and was uniformly adopted by the rulers of the other provinces as well.[6]

Emperor-in-exile Amha Selassie appointed Prince Bekere Fikre-Selassie "Enderase" in right of the Crown Council of Ethiopia in 1993, as his representative, and who still holds the office, as Crown Prince Zera Yacob Amha Selassie has not declared himself Emperor.[7]

Reise Mekwanint

Reise Mekwanint (ርዕሰ መኳንንት rə‘əsä mäkʷanənt, "head of the nobles") was a title granted during the Zemene Mesafint, which raised its holder over all appointed nobles. It was bestowed upon the Enderase, who during that period held most of the (considerably diminished) imperial power. It was last granted to Yohannes IV by his brother-in-law Tekle Giyorgis II (Wagshum Gobeze) before the former deposed the later and seized the throne for himself.

Tsehafi Taezaz

The Tsehafi Taezaz (ጸሐፌ ትእዛዝ ts'äḥafē tə’əzaz, lit. "scribe by command", translated as "Minister of the Pen") was the most powerful post at the Imperial court. According to John Spencer, he was "the one who traditionally walked two steps behind the Emperor to listen to and write down all orders that the latter gave out in the course of an audience or an inspection tour." Spencer adds that under Haile Selassie the Tsehafe Tezaz safeguarded the Great Seal, kept the records of all important appointments, and was responsible for publishing all laws and treaties; "his signature, rather than that of the Emperor, appeared on those [official] publications although the heading in each case referred to His Imperial Majesty."[8] The office was combined with that of Prime Minister during the tenure of Aklilu Habte-Wold (1961–1974).

Afe Negus

Afe Negus (አፈ ንጉሥ ’afä nəgus, "mouth of the King") was originally the title given to the two chief heralds who acted as official spokesmen for the Emperor. As the Emperor never spoke in public, these officials always spoke in public for him, speaking as if they were the Emperor. By 1942, this title was granted only to Justices of the Imperial Supreme Court.[9]

Lique Mekwas

The Lique Mekwas (ሊቀ መኳስ liqä mäkʷas) was the impersonator or double of the Emperor, who accompanied him in battle. Two trusted and highly favored officials were given this title. They always walked or rode on either side of the monarch in battle, or in public processions, dressing as magnificently, or more magnificently then he, in order to distract assassins.[10]

Aqabe Se'at

The Aqabe Se'at (አቃቤ ሰዓት ’aqabē sä‘at, "keeper of time") was a high official, often a clergyman, who was responsible for keeping the Emperor's schedule and had authority over the clergy assigned to the Imperial Court. The position was one of immense power in medieval times, but became largely titular under the Gondarine Emperors and eventually went out of existence.

Blattengeta

The Blattengeta (ብላቴን ጌታ blatēn gēta, "lord of the pages") was a high court official that served as administrator of the Palaces. The title was later used as an honorific.

Blatta

Blatta (ብላታ blata, "page") was the rank of high court officials in charge of maintaining palace protocol and meeting the personal needs of the Imperial family.

Basha

Basha (ባሻ baša) was a rank originally derived from the Turkish (Ottoman)/Egyptian title of Pasha, but considered a lower rank in Ethiopia, whereas Pasha was a high rank at the Turkish and Egyptian courts.

Important offices of the civil government

Negadras

A Negadras (ነጋድራስ nägadras, "head of the merchants") was the appointed leader of a larger town's merchants, who supervised the operations of the markets, the administration of customs, and the collection of taxes.[1] By the end of the 19th century a negadras was often the single most important official in a town, essentially acting as its mayor.

By 1900 the various negadrasoch had been subordinated to the negadras of Addis Ababa, Haile Giyorgis Woldemikael, who by 1906 supervised foreign businesses and diplomatic missions in the capital, the organisation of hand was responsible for granting concessions and contracts to foreign enterprises, making the post the de facto Mayor of Addis Ababa, Chief of police, Minister of Commerce and Minister of Foreign Affairs. These functions were separated by the formation of the first cabinet in 1907, with Haile Giyorgis appointed to those posts. With Haile Giyorgis' removal from office by then-Regent Ras Tafari Makonnen in 1917, the post of negadras of Addis Ababa lost most of its powers to the office of Kantiba, the head of the municipal government, which had been created in 1910, with other towns later following suit.[1]

Kantiba

Kantiba (ከንቲባ käntiba, "mayor" or "Lord Mayor") is a mayor of a large town or city in modern. In ancient times a kantiba was a chief, almost like a governor of a province or more. He has the task to administrate the given areas. He had soldiers. In certain cases the title of kantiba could have passed from father to son, and in some others the title was given to elected individuals for a few years. End of the mandate another person was elected.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Garretson, Peter (November 2000). "Intrigue and Power: Hayle Giyorgis, Addis Ababa's First Mayor". Seleda. II (V). Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Vadala, Alexander Atillio (2011). "Elite Distinction and Regime Change: The Ethiopian Case". Comparative Sociology. 10 (4): 641. doi:10.1163/156913311X590664.

- ↑ "Ethiopia - Tigray 1". Royal Ark. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ethiopia Military Tradition in National Life Library of Congress

- ↑ Edward Ullendorff notes that the title of "Nebura ed" is also used by the head of Basilica Church of St Maryam at Addis Alem, "built by Menelik as the southern Aksum". (The Ethiopians, 2nd ed. [London: Oxford, 1960], p. 109)

- ↑ Zewde, Bahru; Pausewang, Siegfried (2002). Ethiopia: The Challenge of Democracy from Below. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute. p. 10. ISBN 9171065016.

- ↑ Copley, Gregory. "The Structure and Role of the Crown Council of Ethiopia". Imperial Ethiopia Online. The Crown Council of Ethiopia. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Spencer, John (1984). Ethiopia at Bay: A personal account of the Haile Selassie years. Algonac, Michigan: Reference Publications. p. 118. ISBN 0917256255. ISBN 9780917256257.

- ↑ Margary Perham, The Government of Ethiopia, second edition (London: Faber and Faber, 1969), p. 154

- ↑ Perham, The Government of Ethiopia, p. 86

Sources

- Ethiopia: a country study. Edited by Thomas P. Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O., 1993. Online at http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/ettoc.html#et0163