Book of Enoch

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Book of Enoch (also 1 Enoch;[1] Ge'ez: መጽሐፈ ሄኖክ mätṣḥäfä henok) is an ancient Jewish religious work, ascribed by tradition to Enoch, the great-grandfather of Noah, although modern scholars estimate the older sections (mainly in the Book of the Watchers) to date from about 300 BC, and the latest part (Book of Parables) probably to the first century BC.[2]

It is not part of the biblical canon as used by Jews, apart from Beta Israel. Most Christian denominations and traditions may accept the Books of Enoch as having some historical or theological interest, but they generally regard the Books of Enoch as non-canonical or non-inspired.[3] It is regarded as canonical by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, but not by any other Christian groups.

It is wholly extant only in the Ge'ez language, with Aramaic fragments from the Dead Sea Scrolls and a few Greek and Latin fragments. For this and other reasons, the traditional Ethiopian belief is that the original language of the work was Ge'ez, whereas non-Ethiopian scholars tend to assert that it was first written in either Aramaic or Hebrew; Ephraim Isaac suggests that the Book of Enoch, like the Book of Daniel, was composed partially in Aramaic and partially in Hebrew.[4]:6 No Hebrew version is known to have survived. It is asserted in the book itself that its author was Enoch, before the Biblical Flood.

Some of the authors of the New Testament were familiar with some of the content of the story.[5] A short section of 1 Enoch (1:9) is cited in the New Testament, Epistle of Jude, Jude 1:14–15, and is attributed there to "Enoch the Seventh from Adam" (1 En 60:8), although this section of 1 Enoch is a midrash on Deuteronomy 33. Several copies of the earlier sections of 1 Enoch were preserved among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Content

The first part of the Book of Enoch describes the fall of the Watchers, the angels who fathered the Nephilim. The remainder of the book describes Enoch's visits to heaven in the form of travels, visions and dreams, and his revelations.

The book consists of five quite distinct major sections (see each section for details):

- The Book of the Watchers (1 Enoch 1–36)

- The Book of Parables of Enoch (1 Enoch 37–71) (also called the Similitudes of Enoch)

- The Astronomical Book (1 Enoch 72–82) (also called the Book of the Heavenly Luminaries or Book of Luminaries)

- The Book of Dream Visions (1 Enoch 83–90) (also called the Book of Dreams)

- The Epistle of Enoch (1 Enoch 91–108)

Most scholars believe that these five sections were originally independent works[6] (with different dates of composition), themselves a product of much editorial arrangement, and were only later redacted into what we now call 1 Enoch.

Canonicity

Judaism

Although evidently widely known during the development of the Hebrew Bible canon, 1 Enoch was excluded from both the formal canon of the Tanakh and the typical canon of the Septuagint and therefore, also from the writings known today as the Deuterocanon.[7][8] One possible reason for Jewish rejection of the book might be the textual nature of several early sections of the book that make use of material from the Torah; for example, 1 En 1 is a midrash of Deuteronomy 33.[9][10] The content, particularly detailed descriptions of fallen angels, would also be a reason for rejection from the Hebrew canon at this period – as illustrated by the comments of Trypho the Jew when debating with Justin Martyr on this subject: "The utterances of God are holy, but your expositions are mere contrivances, as is plain from what has been explained by you; nay, even blasphemies, for you assert that angels sinned and revolted from God." (Dialogue 79)[11]

Christianity

By the 4th century, the Book of Enoch was mostly excluded from Christian canons, and it is now regarded as scripture by only the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

References in the New Testament

"Enoch, the seventh from Adam" is quoted, in Jude 1:14–15:

And Enoch also, the seventh from Adam, prophesied of these, saying, Behold, the Lord cometh with ten thousands of his saints, To execute judgment upon all, and to convict all that are ungodly among them of all their ungodly deeds which they have ungodly committed, and of all their hard speeches which ungodly sinners have spoken against him.

Compare this with Enoch 1:9, translated from the Ethiopic (found also in Qumran scroll 4Q204=4QEnochc ar, col I 16–18):[12]

And behold! He cometh with ten thousands of His Saints To execute judgment upon all, And to destroy all the ungodly: And to convict all flesh Of all the works of their ungodliness which they have ungodly committed, And of all the hard things which ungodly sinners have spoken against Him.

Compare this also with what may be the original source of 1 En 1:9 in Deuteronomy 33:2:[13][14][15]

The Lord came from Sinai and dawned from Seir upon us; he shone forth from Mount Paran; he came from the ten thousands of Saints, with flaming fire at his right hand.

Under the heading of canonicity, it is not enough to merely demonstrate that something is quoted. Instead, it is necessary to demonstrate the nature of the quotation.[16] In the case of the Jude 1:14 quotation of 1 Enoch 1:9, it would be difficult to argue that Jude does not quote Enoch as an historical prophet since he cites Enoch by name. However, there remains a question as to whether the author of Jude attributed the quotation believing the source to be the historical Enoch before the flood or a midrash of Deut 33:2–3.[17][18][19] The Greek text might seem unusual in stating that "Enoch the Seventh from Adam" prophesied "to" (dative case) not "of" (genitive case) the men, however, this might indicate the Greek meaning “against them” – the dative τούτοις as a dativus incommodi (dative of disadvantage).[20]

Peter H. Davids points to Dead Sea Scrolls evidence but leaves it open as to whether Jude viewed 1 Enoch as canon, deuterocanon, or otherwise: "Did Jude, then, consider this scripture to be like Genesis or Isaiah? Certainly he did consider it authoritative, a true word from God. We cannot tell whether he ranked it alongside other prophetic books such as Isaiah and Jeremiah. What we do know is, first, that other Jewish groups, most notably those living in Qumran near the Dead Sea, also used and valued 1 Enoch, but we do not find it grouped with the scriptural scrolls."[21]

The attribution "Enoch the Seventh from Adam" is apparently itself a section heading taken from 1 Enoch (1 En 60:8, Jude 1:14a) and not from Genesis.[22]

Also, it has been alleged that 1 Peter, (in 1Peter 3:19–20) and 2 Peter (in 2Peter 2:4–5) make reference to some Enochian material.[23]

Reception

The Book of Enoch was considered as scripture in the Epistle of Barnabas (16:4)[24] and by many of the early Church Fathers, such as Athenagoras,[25] Clement of Alexandria,[26] Irenaeus[27] and Tertullian,[28] who wrote c. 200 that the Book of Enoch had been rejected by the Jews because it contained prophecies pertaining to Christ.[29] However, later Fathers denied the canonicity of the book, and some even considered the Epistle of Jude uncanonical because it refers to an "apocryphal" work.[30]

Ethiopic Orthodox Church

The traditional belief of the Ethiopic Orthodox Church, which sees 1 Enoch as an inspired document, is that the Ethiopic text is the original one, written by Enoch himself. They believe that the following opening sentence of Enoch is the first and oldest sentence written in any human language, since Enoch was the first to write letters:

- "ቃለ፡ በረከት፡ ዘሄኖክ፡ ዘከመ፡ ባረከ፡ ኅሩያነ፡ ወጻድቃነ፡ እለ፡ ሀለዉ፡ ይኩኑ"

- "በዕለተ፡ ምንዳቤ፡ ለአሰስሎ፡ ኵሉ፡ እኩያን፡ ወረሲዓን።"

- "Qāla barakat za-Hēnōk za-kama bāraka ḫərūyāna wa-ṣādəqāna 'əlla hallawu yəkūnū ba-ʿəlata məndābē la-'asassəlō kʷəllū 'əkūyān wa-rasīʿān"

- "Word of blessing of Henok, wherewith he blessed the chosen and righteous who would be alive in the day of tribulation for the removal of all wrongdoers and backsliders."

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) does not consider 1 Enoch to be part of its standard canon, though it believes that the original Book of Enoch was an inspired book.[31] The Book of Moses, found within the scriptural canon of the LDS Church, has several similarities to 1 Enoch,[32] including names[33] that have been found in some versions of 1 Enoch, and is believed by the LDS Church to contain extracts from "the ministry, teachings, and visions of Enoch".[34][35][36]

Manuscript tradition

Ethiopic

The most extensive witnesses to the Book of Enoch exist in the Ge'ez language. Robert Henry Charles's critical edition of 1906 subdivides the Ethiopic manuscripts into two families:

Family α: thought to be more ancient and more similar to the Greek versions:

- A – ms. orient. 485 of the British Museum, 16th century, with Jubilees

- B – ms. orient. 491 of the British Museum, 18th century, with other biblical writings

- C – ms. of Berlin orient. Petermann II Nachtrag 29, 16th century

- D – ms. abbadiano 35, 17th century

- E – ms. abbadiano 55, 16th century

- F – ms. 9 of the Lago Lair, 15th century

Family β: more recent, apparently edited texts

- G – ms. 23 of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 18th century

- H – ms. orient. 531 of the Bodleian Library of Oxford, 18th century

- I – ms. Brace 74 of the Bodleian Library of Oxford, 16th century

- J – ms. orient. 8822 of the British Museum, 18th century

- K – ms. property of E. Ullendorff of London, 18th century

- L – ms. abbadiano 99, 19th century

- M – ms. orient. 492 of the British Museum, 18th century

- N – ms. Ethiopian 30 of Monaco of Baviera, 18th century

- O – ms. orient. 484 of the British Museum, 18th century

- P – ms. Ethiopian 71 of the Vatican, 18th century

- Q – ms. orient. 486 of the British Museum, 18th century, lacking chapters 1–60

Additionally, there are the manuscripts used by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church for preparation of the deuterocanonicals from Ge'ez into the targumic Amharic in the bilingual Haile Selassie Amharic Bible (Mashaf qeddus bage'ezenna ba'amaregna yatasafe 4 vols. c.1935).[37]

Aramaic

Eleven Aramaic-language fragments of the Book of Enoch were found in cave 4 of Qumran in 1948[38] and are in the care of the Israel Antiquities Authority. They were translated for and discussed by Józef Milik and Matthew Black in The Books of Enoch.[39] Another translation has been released by Vermes and Garcia-Martinez.[40] Milik described the documents as being white or cream in color, blackened in areas, and made of leather that was smooth, thick and stiff. It was also partly damaged, with the ink blurred and faint.

- 4Q201 = 4QEnoch a ar, Enoch 2:1–5:6; 6:4–8:1; 8:3–9:3,6–8

- 4Q202 = 4QEnoch b ar, Enoch 5:9–6:4, 6:7–8:1, 8:2–9:4, 10:8–12, 14:4–6

- 4Q204 = 4QEnoch c ar, Enoch 1:9–5:1, 6:7, 10:13–19, 12:3, 13:6–14:16, 30:1–32:1, 35, 36:1–4, 106:13–107:2

- 4Q205 = 4QEnoch d ar; Enoch 89:29–31, 89:43–44

- 4Q206 = 4QEnoch e ar; Enoch 22:3–7, 28:3–29:2, 31:2–32:3, 88:3, 89:1–6, 89:26–30, 89:31–37

- 4Q207 = 4QEnoch f ar

- 4Q208 = 4QEnastr a ar

- 4Q209 = 4QEnastr b ar; Enoch 79:3–5, 78:17, 79:2 and large fragments that do not correspond to any part of the Ethiopian text

- 4Q210 = 4QEnastr c ar; Enoch 76:3–10, 76:13–77:4, 78:6–8

- 4Q211 = 4QEnastr d ar; large fragments that do not correspond to any part of the Ethiopian text

- 4Q212 = 4QEn g ar; Enoch 91:10, 91:18–19, 92:1–2, 93:2–4, 93:9–10, 91:11–17, 93:11–93:1

Also at Qumran (cave 1) have been discovered three tiny fragments in Hebrew (8:4–9:4, 106).

Greek and Latin

The 8th-century work Chronographia Universalis by the Byzantine historian George Syncellus preserved some passages of the Book of Enoch in Greek (6:1–9:4, 15:8–16:1). Other Greek fragments known are:

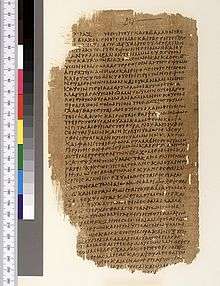

- Codex Panopolitanus (Cairo Papyrus 10759), named also Codex Gizeh or Akhmim fragments, consists of fragments of two 6th-century papyri containing portions of chapters 1–32 recovered by a French archeological team at Akhmim in Egypt and published five years later, in 1892.

- Codex Vaticanus Gr. 1809, f. 216v (11th century): including 89:42–49

- Chester Beatty Papyri XII : including 97:6–107:3 (less chapter 105)

- Oxyrhynchus Papyri 2069: including only a few letters, which made the identification uncertain, from 77:7–78:1, 78:1–3, 78:8, 85:10–86:2, 87:1–3

It has been claimed that several small additional fragments in Greek have been found at Qumran (7QEnoch: 7Q4, 7Q8, 7Q10-13), dating about 100 BC, ranging from 98:11? to 103:15[41] and written on papyrus with grid lines, but this identification is highly contested.

Of the Latin translation, only 1:9 and 106:1–18 are known. The first passage occurs in Pseudo-Cyprian and Pseudo-Vigilius;[42] the second was discovered in 1893 by M. R. James in an 8th-century manuscript in the British Museum and published in the same year.[43]

History

Second Temple period

The 1976 publication by Milik[39] of the results of the paleographic dating of the Enochic fragments found in Qumran made a breakthrough. According to this scholar, who studied the original scrolls for many years, the oldest fragments of the Book of Watchers are dated to 200–150 BC. Since the Book of Watchers shows evidence of multiple stages of composition, it is probable that this work was extant already in the 3rd century BC.[44] The same can be said about the Astronomical Book.

It was no longer possible to claim that the core of the Book of Enoch was composed in the wake of the Maccabean Revolt as a reaction to Hellenization.[45]:93 Scholars thus had to look for the origins of the Qumranic sections of 1 Enoch in the previous historical period, and the comparison with traditional material of such a time showed that these sections do not draw exclusively on categories and ideas prominent in the Hebrew Bible. Some scholars speak even of an "Enochic Judaism" from which the writers of Qumran scrolls were descended.[46] Margaret Barker argues, "Enoch is the writing of a very conservative group whose roots go right back to the time of the First Temple".[47] The main peculiar aspects of the Enochic Judaism are the following:

- the idea of the origin of the evil caused by the fallen angels, who came on the earth to unite with human women. These fallen angels are considered ultimately responsible for the spread of evil and impurity on the earth;[45]:90

- the absence in 1 Enoch of formal parallels to the specific laws and commandments found in the Mosaic Torah and of references to issues like Shabbat observance or the rite of circumcision. The Sinaitic covenant and Torah are not of central importance in the Book of Enoch;[48]:50–51

- the concept of "End of Days" as the time of final judgment that takes the place of promised earthly rewards;[45]:92

- the rejection of the Second Temple's sacrifices considered impure: according to Enoch 89:73, the Jews, when returned from the exile, "reared up that tower (the temple) and they began again to place a table before the tower, but all the bread on it was polluted and not pure";

- a solar calendar in opposition to the lunar calendar used in the Second Temple (a very important aspect for the determination of the dates of religious feasts);

- an interest in the angelic world that involves life after death.[49]

Most Qumran fragments are relatively early, with none written from the last period of the Qumranic experience. Thus, it is probable that the Qumran community gradually lost interest in the Book of Enoch.[50]

The relation between 1 Enoch and the Essenes was noted even before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.[51] While there is consensus to consider the sections of the Book of Enoch found in Qumran as texts used by the Essenes, the same is not so clear for the Enochic texts not found in Qumran (mainly the Book of Parables): it was proposed[52] to consider these parts as expression of the mainstream, but not-Qumranic, essenic movement. The main peculiar aspects of the not-Qumranic units of 1 Enoch are the following:

- a Messiah called "Son of Man", with divine attributes, generated before the creation, who will act directly in the final judgment and sit on a throne of glory (1 Enoch 46:1–4, 48:2–7, 69:26–29)[12]:562–563

- the sinners usually seen as the wealthy ones and the just as the oppressed (a theme we find also in the Psalms of Solomon).

Early influence

Classical Rabbinic literature is characterized by near silence concerning Enoch. It seems plausible that Rabbinic polemics against Enochic texts and traditions might have led to the loss of these books to Rabbinic Judaism.[53]

The Book of Enoch plays an important role in the history of Jewish mysticism: the great scholar Gershom Scholem wrote, "The main subjects of the later Merkabah mysticism already occupy a central position in the older esoteric literature, best represented by the Book of Enoch."[54] Particular attention is paid to the detailed description of the throne of God included in chapter 14 of 1 Enoch.

For the quotation from the Book of Watchers in the Christian Letter of Jude, see section: Canonicity.

There is little doubt that 1 Enoch was influential in molding New Testament doctrines about the Messiah, the Son of Man, the messianic kingdom, demonology, the resurrection, and eschatology.[4]:10 The limits of the influence of 1 Enoch are discussed at length by R.H. Charles[55] E Isaac,[4] and G.W. Nickelsburg[56] in their respective translations and commentaries. It is possible that the earlier sections of 1 Enoch had direct textual and content influence on many Biblical apocrypha, such as Jubilees, 2 Baruch, 2 Esdras, Apocalypse of Abraham and 2 Enoch, though even in these cases, the connection is typically more branches of a common trunk than direct development.[57]

The Greek text was known to, and quoted, both positively and negatively, by many Church Fathers: references can be found in Justin Martyr, Minucius Felix, Irenaeus, Origen, Cyprian, Hippolytus, Commodianus, Lactantius and Cassian.[58]:430 After Cassian and before the modern "rediscovery", some excerpts are given in the Byzantine Empire by the 8th-century monk George Syncellus in his chronography, and in the 9th century, it is listed as an apocryphon of the New Testament by Patriarch Nicephorus.[59]

Rediscovery

Sir Walter Raleigh, in his History of the World (written in 1616 while imprisoned in the Tower of London), makes the curious assertion that part of the Book of Enoch "which contained the course of the stars, their names and motions" had been discovered in Saba (Sheba) in the first century and was thus available to Origen and Tertullian. He attributes this information to Origen,[60] though no such statement is found anywhere in extant versions of Origen.[61]

Outside of Ethiopia, the text of the Book of Enoch was considered lost until the beginning of the seventeenth century, when it was confidently asserted that the book was found in an Ethiopic (Ge'ez) language translation there, and Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc bought a book that was claimed to be identical to the one quoted by the Epistle of Jude and the Church Fathers. Hiob Ludolf, the great Ethiopic scholar of the 17th and 18th centuries, soon claimed it to be a forgery produced by Abba Bahaila Michael.[62]

Better success was achieved by the famous Scottish traveller James Bruce, who, in 1773, returned to Europe from six years in Abyssinia with three copies of a Ge'ez version.[63] One is preserved in the Bodleian Library, another was presented to the royal library of France, while the third was kept by Bruce. The copies remained unused until the 19th century; Silvestre de Sacy, in "Notices sur le livre d'Enoch",[64] included extracts of the books with Latin translations (Enoch chapters 1, 2, 5–16, 22, and 32). From this a German translation was made by Rink in 1801.

The first English translation of the Bodleian/Ethiopic manuscript was published in 1821 by Richard Laurence, titled The Book of Enoch, the prophet: an apocryphal production, supposed to have been lost for ages; but discovered at the close of the last century in Abyssinia; now first translated from an Ethiopic manuscript in the Bodleian Library. Oxford, 1821. Revised editions appeared in 1833, 1838, and 1842.

In 1838, Laurence also released the first Ethiopic text of 1 Enoch published in the West, under the title: Libri Enoch Prophetae Versio Aethiopica. The text, divided into 105 chapters, was soon considered unreliable as it was the transcription of a single Ethiopic manuscript.[65]

In 1833, Professor Andreas Gottlieb Hoffmann of the University of Jena released a German translation, based on Laurence's work, called Das Buch Henoch in vollständiger Uebersetzung, mit fortlaufendem Kommentar, ausführlicher Einleitung und erläuternden Excursen. Two other translations came out around the same time: one in 1836 called Enoch Restitutus, or an Attempt (Rev. Edward Murray) and one in 1840 called Prophetae veteres Pseudepigraphi, partim ex Abyssinico vel Hebraico sermonibus Latine bersi (A. F. Gfrörer). However, both are considered to be poor—the 1836 translation most of all—and is discussed in Hoffmann.[66]

The first critical edition, based on five manuscripts, appeared in 1851 as Liber Henoch, Aethiopice, ad quinque codicum fidem editus, cum variis lectionibus, by August Dillmann. It was followed in 1853 by a German translation of the book by the same author with commentary titled Das Buch Henoch, übersetzt und erklärt. It was considered the standard edition of 1 Enoch until the work of Charles.

The generation of Enoch scholarship from 1890 to World War I was dominated by Robert Henry Charles. His 1893 translation and commentary of the Ethiopic text already represented an important advancement, as it was based on ten additional manuscripts. In 1906 R.H. Charles published a new critical edition of the Ethiopic text, using 23 Ethiopic manuscripts and all available sources at his time. The English translation of the reconstructed text appeared in 1912, and the same year in his collection of The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament.

The publication, in the early 1950s, of the first Aramaic fragments of 1 Enoch among the Dead Sea Scrolls profoundly changed the study of the document, as it provided evidence of its antiquity and original text. The official edition of all Enoch fragments appeared in 1976, by Jozef Milik.

The renewed interest in 1 Enoch spawned a number of other translations: in Hebrew (A. Kahana, 1956), Danish (Hammershaimb, 1956), Italian (Fusella, 1981), Spanish (1982), French (Caquot, 1984) and other modern languages. In 1978 a new edition of the Ethiopic text was edited by Michael Knibb, with an English translation, while a new commentary appeared in 1985 by Matthew Black.

In 2001 George W.E. Nickelsburg published the first volume of a comprehensive commentary on 1 Enoch in the Hermeneia series.[48] Since the year 2000, the Enoch seminar has devoted several meetings to the Enoch literature and has become the center of a lively debate concerning the hypothesis that the Enoch literature attests the presence of an autonomous non-Mosaic tradition of dissent in Second Temple Judaism.

Ge'ez origin theory

Wossenie Yifru (1990) holds that Ge'ez is the language of the original from which the Greek and Aramaic copies were made, pointing out that it is the only language in which the complete text has yet been found.[67]

The Book of the Watchers

This first section of the Book of Enoch describes the fall of the Watchers, the angels who fathered the Nephilim (cf. the bene Elohim, Genesis 6:1–2) and narrates the travels of Enoch in the heavens. This section is said to have been composed in the 4th or 3rd century BC according to Western scholars.[68]

Content

- 1-5. Parable of Enoch on the Future Lot of the Wicked and the Righteous.

- 6-11. The Fall of the Angels: the Demoralization of Mankind: the Intercession of the Angels on behalf of Mankind. The Dooms pronounced by God on the Angels of the Messianic Kingdom.

- 12-16. Dream-Vision of Enoch: his Intercession for Azazel and the fallen angels: and his Announcement of their first and final Doom.

- 17-36. Enoch's Journeys through the Earth and Sheol: Enoch also traveled through a portal shaped as a triangle to heaven.

- 17-19. The First Journey.

- 20. Names and Functions of the Seven Archangels.

- 21. Preliminary and final Place of Punishment of the fallen Angels (stars).

- 22. Sheol or the Underworld.

- 23. The fire that deals with the Luminaries of Heaven.

- 24-25. The Seven Mountains in the North-West and the Tree of Life.

- 26. Jerusalem and the Mountains, Ravines, and Streams.

- 27. The Purpose of the Accursed Valley.

- 28-33. Further Journey to the East.

- 34-35. Enoch's Journey to the North.

- 36. The Journey to the South.

Description

The introduction to the Book of Enoch tells us that Enoch is "a just man, whose eyes were opened by God so that he saw a vision of the Holy One in the heavens, which the sons of God showed to me, and from them I heard everything, and I knew what I saw, but [these things that I saw will] not [come to pass] for this generation, but for a generation that has yet to come."

It discusses God coming to Earth on Mount Sinai with His hosts to pass judgement on mankind. It also tells us about the luminaries rising and setting in the order and in their own time and never change.

Observe and see how (in the winter) all the trees seem as though they had withered and shed all their leaves, except fourteen trees, which do not lose their foliage but retain the old foliage from two to three years till the new comes.

How all things are ordained by God and take place in his own time. The sinners shall perish and the great and the good shall live on in light, joy and peace.

And all His works go on thus from year to year for ever, and all the tasks which they accomplish for Him, and their tasks change not, but according as God hath ordained so is it done.

The first section of the book depicts the interaction of the fallen angels with mankind; Sêmîazâz compels the other 199 fallen angels to take human wives to "beget us children".

And Semjâzâ, who was their leader, said unto them: "I fear ye will not indeed agree to do this deed, and I alone shall have to pay the penalty of a great sin." And they all answered him and said: "Let us all swear an oath, and all bind ourselves by mutual imprecations not to abandon this plan but to do this thing." Then sware they all together and bound themselves by mutual imprecations upon it. And they were in all two hundred; who descended in the days of Jared on the summit of Mount Hermon, and they called it Mount Hermon, because they had sworn and bound themselves by mutual imprecations upon it.

The names of the leaders are given as "Samyaza (Shemyazaz), their leader, Araqiel, Râmêêl, Kokabiel, Tamiel, Ramiel, Dânêl, Chazaqiel, Baraqiel, Asael, Armaros, Batariel, Bezaliel, Ananiel, Zaqiel, Shamsiel, Satariel, Turiel, Yomiel, Sariel."

This results in the creation of the Nephilim (Genesis) or Anakim/Anak (Giants) as they are described in the book:

And they became pregnant, and they bare great giants, whose height was three hundred ells:[69] Who consumed all the acquisitions of men. And when men could no longer sustain them, the giants turned against them and devoured mankind. And they began to sin against birds, and beasts, and reptiles, and fish, and to devour one another's flesh, and drink the blood.

It also discusses the teaching of humans by the fallen angels, chiefly Azâzêl:

And Azâzêl taught men to make swords, and knives, and shields, and breastplates, and made known to them the metals of the earth and the art of working them, and bracelets, and ornaments, and the use of antimony, and the beautifying of the eyelids, and all kinds of costly stones, and all colouring tinctures. And there arose much godlessness, and they committed fornication, and they were led astray, and became corrupt in all their ways. Semjâzâ taught enchantments, and root-cuttings, Armârôs the resolving of enchantments, Barâqîjâl, taught astrology, Kôkabêl the constellations, Ezêqêêl the knowledge of the clouds, Araqiêl the signs of the earth, Shamsiêl the signs of the sun, and Sariêl the course of the moon.

Michael, Uriel, Raphael, and Gabriel appeal to God to judge the inhabitants of the world and the fallen angels. Uriel is then sent by God to tell Noah of the coming cataclysm and what he needs to do.

Then said the Most High, the Holy and Great One spoke, and sent Uriel to the son of Lamech, and said to him: Go to Noah and tell him in my name "Hide thyself!" and reveal to him the end that is approaching: that the whole earth will be destroyed, and a deluge is about to come upon the whole earth, and will destroy all that is on it. And now instruct him that he may escape and his seed may be preserved for all the generations of the world.

God commands Raphael to imprison Azâzêl:

the Lord said to Raphael: "Bind Azâzêl hand and foot, and cast him into the darkness: and make an opening in the desert, which is in Dûdâêl (God's Kettle/Crucible/Cauldron), and cast him therein. And place upon him rough and jagged rocks, and cover him with darkness, and let him abide there for ever, and cover his face that he may not see light. And on the day of the great judgement he shall be cast into the fire. And heal the earth which the angels have corrupted, and proclaim the healing of the earth, that they may heal the plague, and that all the children of men may not perish through all the secret things that the Watchers have disclosed and have taught their sons. And the whole earth has been corrupted through the works that were taught by Azâzêl: to him ascribe all sin."

God gave Gabriel instructions concerning the Nephilim and the imprisonment of the fallen angels:

And to Gabriel said the Lord: "Proceed against the biters and the reprobates, and against the children of fornication: and destroy [the children of fornication and] the children of the Watchers from amongst men [and cause them to go forth]: send them one against the other that they may destroy each other in battle ..."

Some, including R.H. Charles, suggest that "biters" should read "bastards", but the name is so unusual that some believe that the implication that is made by the reading of "biters" is more or less correct.

The Lord commands Michael to bind the fallen angels.

And the Lord said unto Michael: "Go, bind Semjâzâ and his associates who have united themselves with women so as to have defiled themselves with them in all their uncleanness. 12. And when their sons have slain one another, and they have seen the destruction of their beloved ones, bind them fast for seventy generations in the valleys of the earth, till the day of their judgement and of their consummation, till the judgement that is for ever and ever is consummated. 13. In those days they shall be led off to the abyss of fire: (and) to the torment and the prison in which they shall be confined for ever. And whosoever shall be condemned and destroyed will from thenceforth be bound together with them to the end of all generations. ..."

Book of Parables

Chapters 37–71 of the Book of Enoch are referred to as the Book of Parables. The scholarly debate centers on these chapters. The Book of Parables appears to be based on the Book of Watchers, but presents a later development of the idea of final judgement and of eschatology, concerned not only with the destiny of the fallen angels but also that of the evil kings of the earth. The Book of Parables uses the expression Son of Man for the eschatological protagonist, who is also called “Righteous One”, “Chosen One”, and “Messiah”, and sits on the throne of glory in the final judgment.[70] The first known use of The Son of Man as a definite title in Jewish writings is in 1 Enoch, and its use may have played a role in the early Christian understanding and use of the title.[71]

It has been suggested that the Book of Parables, in its entirety, is a later addition. Pointing to similarities with the Sibylline Oracles and other earlier works, in 1976, J.T. Milik dated the Book of Parables to the third century. He believed that the events in the parables were linked to historic events dating from 260 to 270 CE.[72] This theory is in line with the beliefs of many scholars of the 19th century, including Lucke (1832), Hofman (1852), Wiesse (1856), and Phillippe (1868). According to this theory, these chapters were written in later Christian times by a Jewish Christian to enhance Christian beliefs with Enoch's authoritative name. In a 1979 article, Michael Knibb followed Miliks' reasoning and suggested that because no fragments of chapters 37–71 were found at Qumran, a later date was likely. Knibb would continue this line of reasoning in later works.[73][74]: 417 In addition to being missing from Qumran, Chapters 37–71 are also missing from the Greek translation.[74]: 417 Currently no firm consensus has been reached among scholars as to the date of the writing of the Book of Parables. Milik’s date of as late as 270 CE, however, has been rejected by most scholars. David W. Suter suggests that there is a tendency to date the Book of Parables to between 50 BCE and 117 CE.[74]: 415–416

In 1893, Robert Charles judged Chapter 71 to be a later addition. He would later change his opinion[75]: 1 and give an early date for the work between 94 and 64 BCE.[76]: LIV The 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia states that Son of Man is found in the Book of Enoch, but never in the original material. It occurs in the "Noachian interpolations" (lx. 10, lxxi. 14), in which it has clearly no other meaning than 'man'.[77] The author of the work misuses or corrupts the titles of the angels.[76]: 16 Charles views the title Son of Man, as found in the Book of Parables, as referring to a supernatural person, a Messiah who is not of human descent.[76]: 306–309 In that part of the Book of Enoch known as the Similitudes, it has the technical sense of a supernatural Messiah and judge of the world (xlvi. 2, xlviii. 2, lxx. 27); universal dominion and preexistence are predicated of him (xlviii. 2, lxvii. 6). He sits on God's throne (xlv. 3, li. 3), which is his own throne. Though Charles does not admit it, these passages betray Christian redaction and emendation.[77] Many scholars have suggested that passages in the Book of Parables are Noachian interpolations. These passages seem to interrupt the flow of the narrative. Darrell D. Hannah suggests that these passages are not, in total, novel interpolations, but rather derived from an earlier Noah apocryphon. He believes that some interpolations refer to Herod the Great and should be dated to around 4 BCE.[74]: 472–477

In addition to the theory of Noachian interpolations, which perhaps a majority of scholars support, most scholars currently believe that Chapters 70–71 are a later addition in part or in whole.[74]: 76[74]: 472–473[78] Chapter 69 ends with, "This is the third parable of Enoch." Like Elijah, Enoch is generally thought to have been brought up to Heaven by God while still alive, but some have suggested that the text refers to Enoch as having died a natural death and ascending to Heaven. The Son of Man is identified with Enoch. The text implies that Enoch had previously been enthroned in heaven.[79] Chapters 70–71 seem to contradict passages earlier in the parable where the Son of Man is a separate entity. The parable also switches from third person singular to first person singular.[78] James H. Charlesworth rejects the theory that chapters 70–71 are later additions. He believes that no additions were made to the Book of Parables.[74]: 450–468[75]: 1–12 In his earlier work, the implication is that a majority of scholars agreed with him.[80]

Content

XXXVIII–XLIV. The First Parable.

- XXXVIII. The Coming Judgement of the Wicked.

- XXXIX. The Abode of the Righteous and the Elect One: the Praises of the Blessed.

- XL-XLI. 2. The Four Archangels.

- XLI. 3–9. Astronomical Secrets.

- XLII. The Dwelling-places of Wisdom and of Unrighteousness.

- XLIII–XLIV. Astronomical Secrets.

XLV–LVII. The Second Parable.

- XLV. The Lot of the Apostates: the New Heaven and the New Earth.

- XLVI. The Ancient of Days and the Son of Man.

- XLVII. The Prayer of the Righteous for Vengeance and their Joy at its coming.

- XLVIII. The Fount of Righteousness: the Son of Man -the Stay of the Righteous: Judgement of the Kings and the Mighty.

- XLIX. The Power and Wisdom of the Elect One.

- L. The Glorification and Victory of the Righteous: the Repentance of the Gentiles.

- LI. The Resurrection of the Dead, and the Separation by the Judge of the Righteous and the Wicked.

- LII. The Six Metal Mountains and the Elect One.

- LIII–LIV. The Valley of Judgement: the Angels of Punishment: the Communities of the Elect One.

- LIV.7.–LV.2. Noachic Fragment on the first World Judgement.

- LV.3.–LVI.4. Final Judgement of Azazel, the Watchers and their children.

- LVI.5–8. Last Struggle of the Heathen Powers against Israel.

- LVII. The Return from the Dispersion.

LVIII–LXXI. The Third Parable.

- LVIII. The Blessedness of the Saints.

- LIX. The Lights and the Thunder.

- Book of Noah fragments]

- LX. Quaking of the Heaven: Behemoth and Leviathan: the Elements.

- LXI. Angels go off to measure Paradise: the Judgement of the Righteous by the Elect One: the Praise of the Elect One and of God.

- LXII. Judgement of the Kings and the Mighty: Blessedness of the Righteous.

- LXIII. The unavailing Repentance of the Kings and the Mighty.

- LXIV. Vision of the Fallen Angels in the Place of Punishment.

- LXV. Enoch foretells to Noah the Deluge and his own Preservation.

- LXVI. The Angels of the Waters bidden to hold them in Check.

- LXVII. God's Promise to Noah: Places of Punishment of the Angels and of the Kings.

- LXVIII. Michael and Raphael astonished at the Severity of the Judgement.

- LXIX. The Names and Functions of the (fallen Angels and) Satans: the secret Oath.

- LXX. The Final Translation of Enoch.

- LXXI. Two earlier Visions of Enoch.

The Astronomical Book

| Months 1,4,7,10 | Months 2,5,8,11 | Months 3,6,9,12 | |||||||||||||

| Wed | 1 | 8 | 15 | 22 | 29 | 6 | 13 | 20 | 27 | 4 | 11 | 18 | 25 | ||

| Thurs | 2 | 9 | 16 | 23 | 30 | 7 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 5 | 12 | 19 | 26 | ||

| Fri | 3 | 10 | 17 | 24 | 1 | 8 | 15 | 22 | 29 | 6 | 13 | 20 | 27 | ||

| Sat | 4 | 11 | 18 | 25 | 2 | 9 | 16 | 23 | 30 | 7 | 14 | 21 | 28 | ||

| Sun | 5 | 12 | 19 | 26 | 3 | 10 | 17 | 24 | 1 | 8 | 15 | 22 | 29 | ||

| Mon | 6 | 13 | 20 | 27 | 4 | 11 | 18 | 25 | 2 | 9 | 16 | 23 | 30 | ||

| Tues | 7 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 5 | 12 | 19 | 26 | 3 | 10 | 17 | 24 | 31 | ||

Four fragmentary editions of the Astronomical Book were found at Qumran, 4Q208-211.[82] 4Q208 and 4Q209 have been dated to the beginning of the 2nd century BC, providing a terminus ante quem for the Astronomical Book of the 3rd century BC.[83] The fragments found in Qumran also include material not contained in the later versions of the Book of Enoch.[81][83][84]

This book contains descriptions of the movement of heavenly bodies and of the firmament, as a knowledge revealed to Enoch in his trips to Heaven guided by Uriel, and it describes a Solar calendar that was later described also in the Book of Jubilees which was used by the Dead Sea sect. The use of this calendar made it impossible to celebrate the festivals simultaneously with the Temple of Jerusalem.

The year was composed from 364 days, divided in four equal seasons of ninety-one days each. Each season was composed of three equal months of thirty days, plus an extra day at the end of the third month. The whole year was thus composed of exactly fifty-two weeks, and every calendar day occurred always on the same day of the week. Each year and each season started always on Wednesday, which was the fourth day of the creation narrated in Genesis, the day when the lights in the sky, the seasons, the days and the years were created.[81]:94–95 It is not known how they used to reconcile this calendar with the tropical year of 365.24 days (at least seven suggestions have been made), and it is not even sure if they felt the need to adjust it.[81]:125–140

In Chapter LXXI, the day is defined as having eighteen parts, and the longest period of daylight is twelve parts. This definition puts the origins of the Book of Luminaries either above or below the 47th parallel. Chapter LXXVIII relates that "heaven collapsed and was borne off and fell to the earth" which describes an event consistent with Plato's description of the sun rising in the West. These descriptions, as well as the view of the 'seven stars imprisoned" in Chapter XVIII can only be accommodated by a southern geography in a time far more ancient than generally associated with Enoch. These conditions are described to Enoch by the 'Watchers' - ancient astrologers, <Enoch and the Watchers: Chronology of the Primeval Gods and the Western Sunrise: The Origins of Western Religion> </https://www.amazon.com/Enoch-Watchers-Chronology-Primeval-Religion-ebook/dp/B01M7WBSL1>

Content

- 72. The Sun

- 73. The Moon and its Phases

- 74. The Lunar Year

- 76. The Twelve Winds and their Portals

- 77. The Four Quarters of the World: the Seven Mountains, the Seven Rivers, Seven Great Islands

- 78. The Sun and Moon: the Waxing and Waning of the Moon

- 79–80.1. Recapitulation of several of the Laws

- 80.2–8. Perversion of Nature and the heavenly Bodies due to the Sin of Men

- 81. The Heavenly Tablets and the Mission of Enoch

- 82. Charge given to Enoch: the four Intercalary days: the Stars which lead the Seasons and the Months

The Dream Visions

The Book of Dream Visions, containing a vision of a history of Israel all the way down to what the majority have interpreted as the Maccabean Revolt, is dated by most to Maccabean times (about 163–142 BC). According to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church it was written before the Flood.

Content

LXXXIII–LXXXIV. First Dream Vision on the Deluge. LXXXV–XC. Second Dream Vision of Enoch: the History of the World to the Founding of the Messianic Kingdom.

- LXXXVI. The Fall of the Angels and the Demoralization of Mankind.

- LXXXVII. The Advent of the Seven Archangels.

- LXXXVIII. The Punishment of the Fallen Angels by the Archangels.

- LXXXIX.1–9. The Deluge and the Deliverance of Noah.

- LXXXIX.10–27. From the Death of Noah to the Exodus.

- LXXXIX.28–40. Israel in the Desert, the Giving of the Law, the Entrance into Canaan.

- LXXXIX.41–50. From the Time of the Judges to the Building of the Temple.

- LXXXIX.51–67. The Two Kingdoms of Israel and Judah to the Destruction of Jerusalem.

- LXXXIX.68–71. First Period of the Angelic Rulers – from the Destruction of Jerusalem to the Return from Captivity.

- LXXXIX.72–77. Second Period – from the Time of Cyrus to that of Alexander the Great.

- XC.1–5. Third Period – from Alexander the Great to the Graeco-Syrian Domination.

- XC.6–12. Fourth Period Graeco-Syrian Domination to the Maccabean Revolt (debated).

- XC.13–19. The last Assault of the Gentiles on the Jews (where vv. 13–15 and 16–18 are doublets).

- XC.20–27. Judgement of the Fallen Angels, the Shepherds, and the Apostates.

- XC.28–42. The New Jerusalem, the Conversion of the surviving Gentiles, the Resurrection of the Righteous, the Messiah. Enoch awakes and weeps.

Animals in the second dream vision

The second dream vision in this section of the Book of Enoch is an allegorical account of the history of Israel, that uses animals to represent human beings and human beings to represent angels.

One of several hypothetical reconstructions of the meanings in the dream is as follows based on the works of R. H. Charles and G. H. Schodde:

- White color for moral purity; Black color for sin and contamination of the fallen angels; Red color for blood in reference to martyrdom

- White bull is Adam; Female heifer is Eve; Red calf is Abel; Black calf is Cain; White calf is Seth;

- White bull / man is Noah; White bull is Shem; Red bull is Ham, son of Noah; Black bull is Japheth; Lord of the sheep is God; Fallen star is either Samyaza or Azazel; Elephants are Giants; Camels are Nephilim; Asses are Elioud;

- Sheep are the faithful; Rams are leaders; Herds are the tribes of Israel; Wild Asses are Ishmael, and his descendants including the Midianites; Wild Boars are Esau and his descendants, Edom and Amalek; Bears (Hyenas/Wolves in Ethiopic) are the Egyptians; Dogs are Philistines; Tigers are Arimathea; Hyenas are Assyrians; Ravens (Crows) are Seleucids (Syrians); Kites are Ptolemies; Eagles are possibly Macedonians; Foxes are Ammonites and Moabites;

Description

There are a great many links between the first book and this one, including the outline of the story and the imprisonment of the leaders and destruction of the Nephilim. The dream includes sections relating to the book of Watchers:

And those seventy shepherds were judged and found guilty, and they were cast into that fiery abyss. And I saw at that time how a like abyss was opened in the midst of the earth, full of fire, and they brought those blinded sheep. (The fall of the evil ones)

And all the oxen feared them and were affrighted at them, and began to bite with their teeth and to devour, and to gore with their horns. And they began, moreover, to devour those oxen; and behold all the children of the earth began to tremble and quake before them and to flee from them. (The creation of the Nephilim et al.)

86:4, 87:3, 88:2, and 89:6 all describe the types of Nephilim that are created during the times described in The Book of Watchers, though this doesn't mean that the authors of both books are the same. Similar references exist in Jubilees 7:21–22.

The book describes their release from the Ark along with three bulls – white, red, and black, which are Shem, Ham, and Japeth – in 90:9. It also covers the death of Noah, described as the white bull, and the creation of many nations:

And they began to bring forth beasts of the field and birds, so that there arose different genera: lions, tigers, wolves, dogs, hyenas, wild boars, foxes, squirrels, swine, falcons, vultures, kites, eagles, and ravens (90:10)

It then describes the story of Moses and Aaron (90:13–15), including the miracle of the river splitting in two for them to pass, and the creation of the stone commandments. Eventually they arrived at a "pleasant and glorious land" (90:40) where they were attacked by dogs (Philistines), foxes (Ammonites, Moabites), and wild boars (Esau).

And that sheep whose eyes were opened saw that ram, which was amongst the sheep, till it forsook its glory and began to butt those sheep, and trampled upon them, and behaved itself unseemly. And the Lord of the sheep sent the lamb to another lamb and raised it to being a ram and leader of the sheep instead of that ram which had forsaken its glory. (David replacing Saul as leader of Israel)

It describes the creation of Solomon's Temple and also the house which may be the tabernacle: "And that house became great and broad, and it was built for those sheep: (and) a tower lofty and great was built on the house for the Lord of the sheep, and that house was low, but the tower was elevated and lofty, and the Lord of the sheep stood on that tower and they offered a full table before Him". This interpretation is accepted by Dillmann (p. 262), Vernes (p. 89), and Schodde (p. 107). It also describes the escape of Elijah the prophet; in 1 Kings 17:2–24, he is fed by "ravens", so if Kings uses a similar analogy, he may have been fed by the Seleucids. "... saw the Lord of the sheep how He wrought much slaughter amongst them in their herds until those sheep invited that slaughter and betrayed His place." This describes the various tribes of Israel "inviting" in other nations "betraying his place" (i.e., the land promised to their ancestors by God).

This part of the book can be taken to be the kingdom splitting into the northern and southern tribes, that is, Israel and Judah, eventually leading to Israel falling to the Assyrians in 721 BC and Judah falling to the Babylonians a little over a century later 587 BC. "And He gave them over into the hands of the lions and tigers, and wolves and hyenas, and into the hand of the foxes, and to all the wild beasts, and those wild beasts began to tear in pieces those sheep"; God abandons Israel for they have abandoned him.

There is also mention of 59 of 70 shepherds with their own seasons; there seems to be some debate on the meaning of this section, some suggesting that it is a reference to the 70 appointed times in 25:11, 9:2, and 1:12. Another interpretation is the 70 weeks in Daniel 9:24. However, the general interpretation is that these are simply angels. This section of the book and another section near the end describe the appointment by God of the 70 angels to protect the Israelites from enduring too much harm from the "beasts and birds". The later section (110:14) describes how the 70 angels are judged for causing more harm to Israel than he desired, found guilty, and "cast into an abyss, full of fire and flaming, and full of pillars of fire."

"And the lions and tigers eat and devoured the greater part of those sheep, and the wild boars eat along with them; and they burnt that tower and demolished that house"; this represents the sacking of Solomon's temple and the tabernacle in Jerusalem by the Babylonians as they take Judah in 587–586 BC, exiling the remaining Jews. "And forthwith I saw how the shepherds pastured for twelve hours, and behold three of those sheep turned back and came and entered and began to build up all that had fallen down of that house". "Cyrus allowed Sheshbazzar, a prince from the tribe of Judah, to bring the Jews from Babylon back to Jerusalem. Jews were allowed to return with the Temple vessels that the Babylonians had taken. Construction of the Second Temple began"; this represents the history of ancient Israel and Judah; the temple was completed in 515 BC.

The first part of the next section of the book seems, according to Western scholars, to clearly describe the Maccabean revolt of 167 BC against the Seleucids. The following two quotes have been altered from their original form to make the hypothetical meanings of the animal names clear.

And I saw in the vision how the (Seleucids) flew upon those (faithful) and took one of those lambs, and dashed the sheep in pieces and devoured them. And I saw till horns grew upon those lambs, and the (Seleucids) cast down their horns; and I saw till there sprouted a great horn of one of those (faithful), and their eyes were opened. And it looked at them and their eyes opened, and it cried to the sheep, and the rams saw it and all ran to it. And notwithstanding all this those (Macedonians) and vultures and (Seleucids) and (Ptolemies) still kept tearing the sheep and swooping down upon them and devouring them: still the sheep remained silent, but the rams lamented and cried out. And those (Seleucids) fought and battled with it and sought to lay low its horn, but they had no power over it. (109:8–12)

All the (Macedonians) and vultures and (Seleucids) and (Ptolemies) were gathered together, and there came with them all the sheep of the field, yea, they all came together, and helped each other to break that horn of the ram. (110:16)

According to this theory, the first sentence most likely refers to the death of High Priest Onias III, whose murder is described in 1 Maccabees 3:33–35 (died c. 171 BC). The "great horn" clearly is not Mattathias, the initiator of the rebellion, as he dies a natural death, described in 1 Maccabees 2:49. It is also not Alexander the Great, as the great horn is interpreted as a warrior who has fought the Macedonians, Seleucids, and Ptolemies. Judas Maccabeus (167 BC–160 BC) fought all three of these, with a large number of victories against the Seleucids over a great period of time; "they had no power over it". He is also described as "one great horn among six others on the head of a lamb", possibly referring to Maccabeus's five brothers and Mattathias. If taken in context of the history from Maccabeus's time, Dillman Chrest Aethiop says the explanation of Verse 13 can be found in 1 Maccabees iii 7; vi. 52; v.; 2 Maccabees vi. 8 sqq., 13, 14; 1 Maccabees vii 41, 42; and 2 Maccabees x v, 8 sqq. Maccabeus was eventually killed by the Seleucids at the Battle of Elasa, where he faced "twenty thousand foot soldiers and two thousand cavalry". At one time, it was believed this passage might refer to John Hyrcanus; the only reason for this was that the time between Alexander the Great and John Maccabeus was too short. However, it has been asserted that evidence shows that this section does indeed discuss Maccabeus.

It then describes: "And I saw till a great sword was given to the sheep, and the sheep proceeded against all the beasts of the field to slay them, and all the beasts and the birds of the heaven fled before their face." This might be simply the "power of God": God was with them to avenge the death. It may also be Jonathan Apphus taking over command of the rebels to battle on after the death of Judas. John Hyrcanus (Hyrcanus I, Hasmonean dynasty) may also make an appearance; the passage "And all that had been destroyed and dispersed, and all the beasts of the field, and all the birds of the heaven, assembled in that house, and the Lord of the sheep rejoiced with great joy because they were all good and had returned to His house" may describe John's reign as a time of great peace and prosperity. Certain scholars also claim Alexander Jannaeus of Judaea is alluded to in this book.

The end of the book describes the new Jerusalem, culminating in the birth of a Messiah:

And I saw that a white bull was born, with large horns and all the beasts of the field and all the birds of the air feared him and made petition to him all the time. And I saw till all their generations were transformed, and they all became white bulls; and the first among them became a lamb, and that lamb became a great animal and had great black horns on its head; and the Lord of the sheep rejoiced over it and over all the oxen.

Still another interpretation, which has just as much as credibility, is that the last chapters of this section simply refer to the infamous battle of Armageddon, where all of the nations of the world march against Israel; this interpretation is supported by the War Scroll, which describes what this epic battle may be like, according to the group(s) that existed at Qumran.

The Epistle of Enoch

Some scholars propose a date somewhere between the 170 BC and the 1st century BC.

This section can be seen as being made up of five subsections,[85] mixed by the final redactor:

- Apocalypse of Weeks (93:1–10, 91:11–17): this subsection, usually dated to the first half of the 2nd century BC, narrates the history of the world using a structure of ten periods (said "weeks"), of which seven regard the past and three regard future events (the final judgment). The climax is in the seventh part of the tenth week where "new heaven shall appear" and "there will be many weeks without number for ever, and all shall be in goodness and righteousness".

- Exhortation (91:1–10, 91:18–19): this short list of exhortations to follow righteousness, said by Enoch to his son Methuselah, looks to be a bridge to next subsection.

- Epistle (92:1–5, 93:11–105:2): the first part of the epistle describes the wisdom of the Lord, the final reward of the just and the punishment of the evil, and the two separate paths of righteousness and unrighteousness. Then there are six oracles against the sinners, the witness of the whole creation against them, and the assurance of the fate after death. According to Boccaccini[52]:131–138 the epistle is composed of two layers: a "proto-epistle", with a theology near the deterministic doctrine of the Qumran group, and a slightly later part (94:4–104:6) that points out the personal responsibility of the individual, often describing the sinners as the wealthy and the just as the oppressed (a theme found also in the Book of Parables).

- Birth of Noah (106–107): this part appears in Qumran fragments separated from the previous text by a blank line, thus appearing to be an appendix. It tells of the deluge and of Noah, who is born already with the appearance of an angel. This text probably derives, as do other small portions of 1 Enoch, from an originally separate book (see Book of Noah), but was arranged by the redactor as direct speech of Enoch himself.

- Conclusion (108): this second appendix was not found in Qumran and is considered to be the work of the final redactor. It highlights the "generation of light" in opposition to the sinners destined to the darkness.

Content

XCII, XCI.1–10, 18–19. Enoch's Book of Admonition for his Children.

- XCI.1–10, 18–19. Enoch's Admonition to his Children.

- XCIII, XCI.12–17. The Apocalypse of Weeks.

- XCI.12–17. The Last Three Weeks.

- XCIV.1–5. Admonitions to the Righteous.

- XCIV.6–11. Woes for the Sinners.

- XCV. Enoch's Grief: fresh Woes against the Sinners.

- XCVI. Grounds of Hopefulness for the Righteous: Woes for the Wicked.

- XCVII. The Evils in Store for Sinners and the Possessors of Unrighteous Wealth.

- XCVIII. Self-indulgence of Sinners: Sin originated by Man: all Sin recorded in Heaven: Woes for the Sinners.

- XCIX. Woes pronounced on the Godless, the Lawbreakers: evil Plight of Sinners in The Last Days: further Woes.

- C. The Sinners destroy each other: Judgement of the Fallen Angels: the Safety of the Righteous: further Woes for the Sinners.

- CI. Exhortation to the fear of God: all Nature fears Him but not the Sinners.

- CII. Terrors of the Day of Judgement: the adverse Fortunes of the Righteous on the Earth.

- CIII. Different Destinies of the Righteous and the Sinners: fresh Objections of the Sinners.

- CIV. Assurances given to the Righteous: Admonitions to Sinners and the Falsifiers of the Words of Uprightness.

- CV. God and the Messiah to dwell with Man.

- CVI–CVII. (first appendix) Birth of Noah.

- CVIII. (second appendix) Conclusion.

Names of the fallen angels

Some of the fallen angels that are given in 1 Enoch have other names, such as Rameel ('morning of God'), who becomes Azazel, and is also called Gadriel ('wall of God') in Chapter 68. Another example is that Araqiel ('Earth of God') becomes Aretstikapha ('world of distortion') in Chapter 68.

Azaz, as in Azazel, means strength, so the name Azazel can refer to 'strength of God'. But the sense in which it is used most probably means 'impudent' (showing strength towards), which results in 'arrogant to God'. This is also a key point in modern thought that Azazel is Satan.

Nathaniel Schmidt states "the names of the angels apparently refer to their condition and functions before the fall," and lists the likely meanings of the angels' names in the Book of Enoch, noting that "the great majority of them are Aramaic."[86]

The name suffix -el means 'God' (see list of names referring to El), and is used in the names of high-ranking angels. The archangels' names all include -el, such as Uriel ('flame of God') and Michael ('who is like God').

Another name is given as Gadreel, who is said to have tempted Eve; Schmidt lists the name as meaning 'the helper of God.'[86]

See also

- 2 Enoch

- 3 Enoch

- Apocalyptic literature

- Aramaic Enoch Scroll

- Biblical Pseudepigrapha

- Book of Noah

- The Book of Giants

- Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible

- El Shaddai: Ascension of the Metatron, a 2011 video game inspired by the Book of Enoch

Footnotes

- ↑ There are two other books named "Enoch": 2 Enoch, surviving only in Old Slavonic (Eng. trans. by R. H. Charles 1896) and 3 Enoch (surviving in Hebrew, c. fifth to sixth century A.D.).

- ↑ Fahlbusch E., Bromiley G.W. The Encyclopedia of Christianity: P–Sh page 411, ISBN 0-8028-2416-1 (2004)

- ↑ The Book of Enoch - The Reluctant Messenger. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 Ephraim Isaac 1 Enoch: A New Translation and Introduction in James Charlesworth (ed.) The Old Testament Pseudoepigrapha, vol. 1, pp. 5-89 (New York, Doubleday, 1983, ISBN 0-385-09630-5)

- ↑ Cheyne and Black Encyclopedia Biblica (1899), "Apocalyptic Literature" (column 220) s:Encyclopaedia Biblica/Apocalyptic Literature#II. The Book of Enoch. "The Book of Enoch as translated into Ethiopic belongs to the last two centuries B.C. All the writers of the NT were familiar with it and were more or less influenced by it in thought"

- ↑ Vanderkam, JC. (2004). 1 Enoch: A New Translation. Minneapolis:Fortress. pp. 1ff (ie. preface summary).; Nickelsburg, GW. (2004). 1 Enoch: A Commentary. Minneapolis:Fortress. pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Emanuel Tov and Craig Evans, Exploring the Origins of the Bible: Canon Formation in Historical, Literary, and Theological Perspective, Acadia 2008

- ↑ Philip R. Davies, Scribes and Schools: The Canonization of the Hebrew Scriptures London: SPCK, 1998

- ↑ E Isaac, in Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, ed. Charlesworth, Doubleday, 1983

- ↑ "1 Enoch contains three [geographical] name midrashim [on] Mt. Hermon, Dan, and Abel Beit-Maacah" Esther and Hanan Eshel, George W.E. Nickelsburg in perspective: an ongoing dialogue of learning p459. Also in Esther and Hanan Eshel, Toponymic Midrash in 1 Enoch and in Other Second Temple Jewish Literature, Historical and Philological Studies on Judaism 2002 Vol24 pp. 115–130

- ↑ transl. P. Schaff Early Christian Fathers http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/01286.htm

- 1 2 Clontz, TE; Clontz, J (2008), The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh, Cornerstone, p. 711, ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5.

- ↑ "1.9 In 'He comes with ten thousands of His Saints the text reproduces the Massoretic of Deut.33,2 in reading ATAH = erchetai, whereas the three Targums, the Syriac and Vulgate read ATIH, = met'autou. Here the LXX diverges wholly. The reading ATAH is recognised as original. The writer of 1–5 therefore used the Hebrew text and presumably wrote in Hebrew." R.H. Charles, Book of Enoch: Together with a Reprint of the Greek Fragments London 1912, p. lviii

- ↑ "We may note especially that 1:1, 3–4, 9 allude unmistakably to Deuteronomy 33:1–2 (along with other passages in the Hebrew Bible), implying that the author, like some other Jewish writers, read Deuteronomy 33–34, the last words of Moses in the Torah, as prophecy of the future history of Israel, and 33:2 as referring to the eschatological theophany of God as judge." Richard Bauckham, The Jewish world around the New Testament: collected essays. 1999 p. 276

- ↑ "The introduction… picks up various biblical passages and re-interprets them, applying them to Enoch. Two passages are central to it The first is Deuteronomy 33:1 … the second is Numbers 24:3–4 Michael E. Stone Selected studies in pseudepigrapha and apocrypha with special reference to the Armenian Tradition (Studia in Veteris Testamenti Pseudepigrapha No 9) p. 422.

- ↑ Barton, John (2007), The Old Testament: Canon, Literature and Theology Society for Old Testament Study.

- ↑ Nickelsburg, op.cit. see index re. Jude

- ↑ Bauckham, R. 2 Peter, Jude Word Biblical Commentary Vol. 50, 1983

- ↑ Jerome H. Neyrey 2 Peter, Jude, The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries 1994

- ↑ E. M. Sidebottom, james, Jude and 2 Peter (London: Nelson, 1967), p. 90: '14. of these: lit., 'to these'; Jude has some odd use of the dative'. Also see Wallace D. Greek Grammar beyond the Basics. The unique use of the dative toutois in the Greek text (προεφήτευσεν δὲ καὶ τούτοις) is a departure from normal NT use where the prophet prophesies "to" the audience "concerning" (genitive peri auton) false teachers etc.

- ↑ Peter H. Davids, The Letters of 2 Peter and Jude, The Pillar New Testament commentary (Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2006). 76.

- ↑ Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch, Fortress, 2001

- ↑ Williams, Martin (2011). The doctrine of salvation in the first letter of Peter. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 9781107003286.

- ↑ "Apocalyptic Literature", Encyclopedia Biblica

- ↑ Athenagoras of Athens, in Embassy for the Christians 24

- ↑ Clement of Alexandria, in Eclogae prophetice II

- ↑ Irenaeus, in Adversus haereses IV,16,2

- ↑ Tertullian, in De cultu foeminarum I,3 and in De Idolatria XV

- ↑ The Ante-Nicene Fathers (ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson; vol 4.16: On the Apparel of Women (De cultu foeminarum) I.3: "Concerning the Genuineness of 'The Prophecy of Enoch'")

- ↑ Cf. Gerome, Catal. Script. Eccles. 4.

- ↑ Doctrine and Covenants 107:57

- ↑ Nibley, Hugh (December 1975), "A Strange Thing in the Land: The Return of the Book of Enoch, Part 2", Ensign

- ↑ Nibley, Hugh (August 1977), "A Strange Thing in the Land: The Return of the Book of Enoch, Part 13", Ensign

- ↑ Pearl of Great Price Student Manual. LDS Church. 2000. pp. 3–27.

- ↑ Nibley, Hugh (October 1975). "A Strange Thing in the Land: The Return of the Book of Enoch, Part 1". Ensign.

- ↑ The History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. pp. 132–33.

- ↑ Gabriele Boccaccini Enoch and the Messiah Son of Man: revisiting the Book of parables 2007 p367 "..Ethiopian scholars who produced the targumic Amharic version of 1 Enoch printed in the great bilingual Bible of Emperor Haile Selassi"

- ↑ The Online Critical Pseudepigrapha

- 1 2 Josef T. Milik (with Matthew Black). The Books of Enoch, Aramaic Fragments of Qumran Cave 4 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1976)

- ↑ Vermes 513–515; Garcia-Martinez 246–259

- ↑ P. Flint The Greek fragments of Enoch from Qumran cave 7 in ed.Boccaccini Enoch and Qumran Origins 2005 ISBN 0-8028-2878-7, pp. 224–233.

- ↑ see Beer, Kautzsch, Apokryphen und Pseudepigraphen, l.c. p. 237

- ↑ M.R. James, Apocrypha Anecdota T&S 2.3 Cambridge 1893 pp. 146–150.

- ↑ John Joseph Collins, The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to Jewish Apocalyptic Literature (1998) ISBN 0-8028-4371-9, page 44

- 1 2 3 Gabriele Boccaccini, Roots of Rabbinic Judaism: An Intellectual History, from Ezekiel to Daniel, (2002) ISBN 0-8028-4361-1

- ↑ John W. Rogerson, Judith Lieu, The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies Oxford University Press: 2006 ISBN 0-19-925425-7, page 106

- ↑ Margaret Barker, The Lost Prophet: The Book of Enoch and Its Influence on Christianity 1998 reprint 2005, ISBN 1-905048-18-1, page 19

- 1 2 George W. E. Nickelsburg 1 Enoch: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Fortress: 2001 ISBN 0-8006-6074-9

- ↑ John J. Collins in ed. Boccaccini Enoch and Qumran Origins: New Light on a Forgotten Connection 2005 ISBN 0-8028-2878-7, page 346

- ↑ James C. VanderKam, Peter Flint, Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls 2005 ISBN 0-567-08468-X, page 196

- ↑ see the page "Essenes" in the 1906 JewishEncyclopedia

- 1 2 Gabriele Boccaccini Beyond the Essene Hypothesis (1998) ISBN 0-8028-4360-3

- ↑ Annette Yoshiko Reed, Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity, 2005 ISBN 0-521-85378-8, pag 234

- ↑ Gershom Scholem Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1995) ISBN 0-8052-1042-3, pag 43

- ↑ RH Charles, 1 Enoch SPCK London 1916

- ↑ Nickelsburg 1 Enoch, Fortress, 2001

- ↑ see Nickelsburg, op.cit.

- ↑ P. Sacchi, Apocrifi dell'Antico Testamento 1, ISBN 978-88-02-07606-5

- ↑ Cf. Nicephorus (ed. Dindorf), I. 787

- ↑ "[I]t is questionless that the use of letters was found out in the very infancy of the world, proved by those prophecies written on pillars of stone and brick by Enoch, of which Josephus affirmeth that one of them remained even in his time ... But of these prophecies of Enoch, Saint Jude testifieth; and some part of his books (which contained the course of the stars, their names and motions) were afterward found in Arabia fœlix, in the Dominion of the Queene of Saba (saith Origen) of which Tertullian affirmeth that he had seen and read some whole pages." Walter Raleigh, History of the World, chapter 5, section 6. (Google Books) Raleigh's marginal note reads: "Origen Homil. 1 in Num.", i.e., Origen's Homily 1 on Numbers.

- ↑ For example, see Origen's Homilies on Numbers, translated by Thomas P. Scheck; InterVarsity Press, 2009. ISBN 0830829059. (Google Books)

- ↑ Ludolf, Commentarius in Hist. Aethip., p. 347

- ↑ Bruce, Travels, vol 2, page 422

- ↑ Silvestre de Sacy in Notices sur le livre d'Enoch in the Magazine Encyclopédique, an vi. tome I, p. 382

- ↑ see the judgement on Laurence by Dillmann, Das Buch Henoch, p lvii

- ↑ Hoffmann, Zweiter Excurs, pages 917–965

- ↑ Wossenie Yifru, 1990 Henok Metsiet, Vol. I, Ethiopian Research Council

- ↑ The Origins of Enochic Judaism (ed. Gabriele Boccaccini; Turin: Zamorani, 2002)

- ↑ the Ethiopian text gives 300 cubits (135 m), which is probably a corruption of 30 cubits (13.5 m)

- ↑ George W. E. Nickelsburg; Jacob Neusner; Alan Alan Jeffery Avery-Peck, eds. (2003). Enoch and the Messiah Son of Man: Revisiting the Book of Parables. BRILL. pp. 71–74. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ Charles, R. H. (2004). The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, Volume Two: Pseudepigrapha. Apocryphile Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-9747623-7-1.

- ↑ J.T. Milik with Matthew Black, ed. (1976). The Books of Enoch, Aramaic Fragments of Qumran Cave 4. OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. pp. 95–96.

- ↑ M. A. KNIBB (1979). "The Date of the Parables of Enoch: A Critical Review". Cambridge University Press. pp. 358–359. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gabriele Boccaccini, ed. (2007). Enoch and the Messiah Son of Man: Revisiting the Book of Parables. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- 1 2 James H.Charlesworth and Darrell L. Bock [T&T Clark], eds. (2013). "To be published in a book: Parables of Enoch: A Paradigm Shift" (PDF). Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 R. H. CHARLES, D.Litt., D.D. (1912). The book of Enoch, or, 1 Enoch. OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- 1 2 "SON OF MAN". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- 1 2 Chad T. Pierce (2011). Spirits and the Proclamation of Christ: 1 Peter 3:18-22 in Light of Sin and Punishment Traditions in Early Jewish and Christian Literature. Mohr Siebeck. p. 70. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ Michael Anthony Knibb (2009). Essays on the Book of Enoch and Other Early Jewish Texts and Traditions. BRILL. pp. 139–142. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ James H. Charlesworth (1985). The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha and the New Testament: Prolegomena for the Study of Christian Origins. CUP Archive. p. 89. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Beckwith, Roger T. (1996). Calendar and chronology, Jewish and Christian. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10586-7.

- ↑ Martinez, Florentino Garcia; Tigchelaar, Eibert J.C., eds. (1997). The Dead Sea Scrolls: Study Edition. Brill/Eerdmans. pp. 430–443. ISBN 0-8028-4493-6.

- 1 2 Nickelsburg, George W. (2005). Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishnah, 2 ed. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-8006-3779-8.

- ↑ Jackson, David R. (2004). Enochic Judaism: three defining paradigm exemplars. Continuum. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-567-08165-0.

- ↑ Loren T. Stuckenbruck, 1 Enoch 91–108 (2008) ISBN 3-11-019119-9

- 1 2 Nathaniel Schmidt, "Original Language of the Parables of Enoch," pp. 343–345, in William Rainey Harper, Old Testament and Semitic studies in memory of William Rainey Harper, Volume 2, The University of Chicago Press, 1908

References

- Editions, translations, commentaries

- Andreas Gottlieb Hoffmann. Das Buch Henoch, 2 vols. (Jena: Croecker, 1833–39)

- August Dillmann. Liber Henoch aethiopice (Leipzig: Vogel, 1851)

- August Dillmann. Das Buch Henoch (Leipzig: Vogel 1853)

- William Morfill. The Book of the Secrets of Enoch (1896), from Mss Russian Codex Chludovianus, Bulgarian Codex Belgradensi, Codex Belgradensis Serbius.

- Daniel C. Olson. Enoch: A New Translation (North Richland Hills, TX: Bibal, 2004) ISBN 0-941037-89-4

- Ephraim Isaac, 1(Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch, in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, ed. James H. Charlesworth (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1983–85) ISBN 0-385-09630-5

- George Henry Schodde. The Book of Enoch translated from the Ethiopic with Introduction and notes (Andover: Draper, 1882)

- George W.E. Nickelsburg and James C. VanderKam. 1 Enoch: A New Translation (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2004) ISBN 0-8006-3694-5

- George W.E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch: A Commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001) ISBN 0-8006-6074-9

- Josef T. Milik (with Matthew Black). The Books of Enoch: Aramaic Fragments of Qumran Cave 4 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1976).

- Matthew Black (with James C. VanderKam). The Book of Enoch; or, 1 Enoch (Leiden: Brill, 1985) ISBN 90-04-07100-8

- Michael A. Knibb. The Ethiopic Book Of Enoch., 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1978; repr. 1982)

- Michael Langlois. The First Manuscript of the Book of Enoch. An Epigraphical and Philological Study of the Aramaic Fragments of 4Q201 from Qumran (Paris: Cerf, 2008) ISBN 978-2-204-08692-9

- Richard Laurence. Libri Enoch prophetae versio aethiopica (Oxford: Parker, 1838)

- Richard Laurence. The Book of Enoch (Oxford: Parker, 1821)

- Robert Henry Charles. The Book of Enoch (Oxford: Clarendon, 1893), translated from professor Dillmann's Ethiopic text - The Ethiopic Version of the Book of Enoch (Oxford: Clarendon, 1906)

- Robert Henry Charles. The Book of Enoch or 1 Enoch (Oxford: Clarendon, 1912)

- James H. Charlesworth. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha and the New Testament (CUP Archive: 1985) ISBN 1-56338-257-1 - The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha Vol.1 (1983).

- Sabino Chialà. Libro delle Parabole di Enoc (Brescia: Paideia, 1997) ISBN 88-394-0739-1

- Studies

- Veronika Bachmann. Die Welt im Ausnahmezustand. Eine Untersuchung zu Aussagegehalt und Theologie des Wächterbuches (1 Hen 1–36) (Berlin: de Gruyter 2009) ISBN 978-3-11-022429-0.* Gabriele Boccaccini and John J. Collins (eds.). The Early Enoch Literature (Leiden: Brill, 2007) ISBN 90-04-16154-6

- Gabriele Boccaccini. Beyond the Essene Hypothesis: The Parting of the Ways between Qumran and Enochic Judaism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998) ISBN 0-8028-4360-3

- John J. Collins. The Apocalyptic Imagination (New York: Crossroads, 1984; 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: Eermans 1998) ISBN 0-8028-4371-9

- Florentino Garcia Martinez. Qumran & Apocalyptic: Studies on the Aramaic Texts from Qumran (Leiden: Brill, 1992) ISBN 90-04-09586-1

- Florentino Garcia Martinez & Tigchelaar. The Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition (Brill, 1999) with Aramaic studies from J.T. Milik, Hénoc au pays des aromates.* Andrei A. Orlov. The Enoch-Metatron Tradition (Tuebingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2005) ISBN 3-16-148544-0

- Hedley Frederick Davis Sparks. The Apocryphal Old Testament: 1Enoch, 2Enoch (1984)

- Helge S. Kvanvig. Roots of Apocalyptic: The Mesopotamian Background of the Enoch Figure and of the Son of Man (Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1988) ISBN 3-7887-1248-1

- Issaverdens. Uncanonical Writings of the Old Testament: Vision of Enoch the Just (1900)

- Paolo Sacchi, William J. Short. Jewish Apocalyptic and Its History (Sheffield: Academic 1996) ISBN 1-85075-585-X

- James C. VanderKam. Enoch and the Growth of an Apocalyptic Tradition (Washington: Catholic Biblical Association of America, 1984) ISBN 0-915170-15-9

- James C. VanderKam. Enoch: A Man for All Generations (Columbia, SC; University of South Carolina, 1995) ISBN 1-57003-060-X

- Marie-Theres Wacker, Weltordnung und Gericht: Studien zu 1 Henoch 22 (Würzburg: Echter Verlag 1982) ISBN 3-429-00794-1

- Annette Yoshiko Reed. Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005) ISBN 0-521-85378-8

External links

| Wikisource has an incomplete translation of: |

- Text

- Book of the Watchers (Chapters 1–36): Ge'ez text and fragments in Greek, Aramaic, and Latin at the Online Critical Pseudepigrapha

- Ethiopic text online (all 108 chapters)

- R H Charles 1917 Translation

- George H. Schodde 1882 Translation (PDF format).

- Richard Laurence 1883 Translation

- Book of Enoch Interlinear (Including three English and two Swedish translations.)

- Book of Enoch New 2012 Translation with Audio Drama

- August Dillmann (1893). The Book of Enoch (1Enoch) translated from Geez, መጽሐፈ ፡ ሄኖክ ።.

- William Morfill (1896). The Book of the Secrets of Enoch (2Enoch) translated from slave languages (Russian and Serbian - Mss. Codex Chludovianus and Codex Belgradensis Serbius).

- Hugo Odeberg (1928). The Hebrew Book of Henoc (3Enoch), from a Rabbinic perspective and experiment.