Fiat CR.32

| CR.32 | |

|---|---|

| |

| CR.32 of Regia Aeronautica in 1939 | |

| Role | Fighter |

| Manufacturer | Fiat |

| Designer | Celestino Rosatelli |

| First flight | 28 April 1933 |

| Introduction | 1933 |

| Retired | 1953 Spanish Air Force[1] |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | Regia Aeronautica Hungarian Air Force Spanish Air Force Chinese Nationalist Air Force |

| Produced | c. March 1934 – February 1936 |

| Number built | 1052 [2] |

| Variants | Fiat CR.42 |

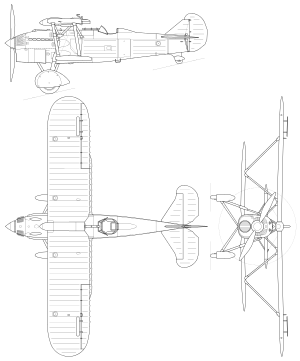

The Fiat CR.32 was an Italian biplane fighter used in the Spanish Civil War and World War II. It was compact, robust and highly manoeuvrable and gave impressive displays all over Europe in the hands of the Italian Pattuglie Acrobatiche.[3] The CR.32 fought in North and East Africa, in Albania, and in the Mediterranean theatre. It saw service in the air forces of China, Austria, Hungary, Paraguay and Venezuela. Used extensively in the Spanish Civil War, it gained a reputation as one of the most outstanding fighter biplanes of all time.[4] It was overtaken subsequently by more advanced monoplane designs and was obsolete by 1939.[5]

Development

The Fiat CR.32 was designed by Celestino Rosatelli. Derived from earlier Fiat CR.30 designs, the CR.32 was a more streamlined and smaller biplane fighter. The prototype MM.201 first flew from the Fiat company airstrip at Turin on 28 April, 1933.[4]

Design

The fuselage had the same structure as the CR.30, utilizing aluminium and steel tubes covered by duraluminium on the nose up to the cockpit, on the back, in the lower section under the tail, and with fabric on the sides and belly. The wings and tail also had a mixed structure, with an aluminium frame covered by fabric. A notable feature was that the lower wing was shorter than the upper wing making it a sesquiplane. Ailerons were only on the upper wings. Armament initially included two 7.7 mm (.030 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns (later two 12.7 mm (.5 in) Breda-SAFAT), located on top of the engine cowling, with 350 rounds each.

The engine was the water-cooled Fiat A.30 R.A.. Designed in 1930, it was a 60° V 12, producing 447 kW (600 hp) at 2,600 rpm, inspired by the American Curtiss D-12. It drove a 2.82 meter (9 ft 4 in) two-blade metal propeller with pitch only adjustable on the ground, not in flight. The engine did not use the usual avio-petrol but a mixture of petrol (55%), alcohol (23%) and benzole (22%). The main fuel tank, located between the engine and cockpit, carried 325 litres (85.9 US gal). There was another small 25 liter (6.6 US gal) tank in the "torpedo" fairing in the center of the upper wing.

Although fully instrumented, the RA.80-1 radio was optional.[6]

Operational history

The new biplane was an instant success. After a period of testing, the first production orders were received in March 1934, and the type soon equipped the 1°, 3° and 4° Stormi of the Regia Aeronautica.[4] The CR.32 was well liked by its crews, being very maneuverable and having a strong fuselage structure.

The Fiat biplanes were used for many aerobatic shows, in Italy and abroad. When foreign statesmen visited the Holy City, the 4° Stormo, Regia Aeronautica élite unit, based in Rome, put on impressive displays with formations of five or ten aircraft. In 1936, air shows were organized in other European capitals and major cities, and, during the following year, in South America. When the team returned, a brilliant display was put on in Berlin.[7]

Spain

In 1938 Spain acquired a license to build the CR.32. Hispano Aviación built 100 examples under the designation HA-132-L Chirri, some of these remaining in service as C.1 aerobatic trainers up to 1953.[7]

The Fiat CR.32 was used extensively in the Spanish Civil War on the side of the Nationalist military rebellion against the Spanish Republic. At least 380 took part in the air battles fought over Spain, proving formidable adversaries to the Soviet Polikarpov I-15 and I-16 monoplanes that formed the backbone of the Spanish Republican Air Force.[8] It had its baptism of fire in 1936. On 18 August the first 12 CR.32 Freccias arrived in Spain and formed the Squadriglia Gamba di Ferro, Cucaracha, and Asso di Bastoni of 3° Stormo; three days later Tenente Vittorino Ceccherelli, a Gold Medal of Military Valor winner, shot down the first enemy aircraft, a Nieuport 52, over Cordoba.[6] In total, the Italian government sent 365–405 C.R.32s to Spain while 127–131 were delivered directly to Nationalist aviation units. Six aircraft were captured by Republican forces, with one sent to the USSR for evaluation.[9]

Thanks to the agile CR.32, the Italians managed to gain air superiority over their Fuerzas Aéreas de la República Española opponents, who flew a motley collection of very different, often obsolete aircraft. The Fiat biplane proved to be effective, with the Aviazione Legionaria claiming 60 (48 confirmed) modern Russian Tupolev SB bombers, once believed impossible to intercept, 242 Polikarpov I-15 biplane fighters, and 240 Polikarpov I-16 monoplane fighters, plus another hundred not confirmed. C.R.32 losses were only 73.[6] According to other sources, of the 376 Fiat shipped to Spain, 175 (43 Spanish operated and 132 Italian) were lost, including 99 (26 Spanish and 73 Italian) shot down, while, by January 1939, the number of I-15s shot down was just 88.[10]

Spanish aces

The top scoring CR.32 ace was Spaniard Joaquín García Morato y Castaño, who was the leading Nationalist fighter pilot of the Spanish Civil War. He achieved 36 of his 40 victories flying the Fiat biplane. He used the same aircraft, which carried the number 3-51 on the fuselage, until his death. In April 1939, with the war over, Morato fatally crashed his faithful 3-51 while performing low aerobatics.[11]

Another Nationalist CR.32 ace was Capitán Manuel Vázquez Sagastizábal, who claimed 21 1⁄3 victories with Grupo 2-G-3, before he was shot down and killed on 23 January 1939. Comandante Angel Salas Larrazabal, after one kill flying a Nieuport-Delage 52, flew CR.32s, shooting down, on 29 October 1936, the first of the fast Soviet monoplane Tupolev SB-2 bombers to fall to Nationalist fighters. He shot down four more aircraft with the CR.32 before moving to a Heinkel He 51 unit. After two more victories, he joined the new Grupo 2-G-3. With this unit, again flying CR.32s, he raised his score to 16, including three SB-2s and an I-16 in a single sortie on 2 September 1938. Capitán Miguel Guerrero Garcia achieved nine of his 13 victories flying the Fiat biplane: four I-15s, three “Papagayos” (R-5s and Polikarpov-RZs assault bombers), and two I-16s.[12]

World War II

The aerobatic characteristics of the CR.32 and its success in Spain misled the Italian air ministry, which was convinced that a biplane fighter still had potential as a weapon of war.[4] Consequently, in May 1939, prior to Italy entering World War II, CR.32 fighters in bis, ter, and quater versions represented two thirds of all fighters in the Regia Aeronautica. A total of 288 were based in Italy and North Africa, while 24 were stationed in East Africa. When Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10 June 1940, 36 "Freccias" together with 51 Fiat CR.42s formed the operational fighter force of the Regia Aeronautica in Libya.[13] The first combat between CR.32s and British aircraft came the following day. Six CR.32s intercepted a formation of Bristol Blenheim bombers attacking the airfield at El Adem, claiming two Blenheims shot down and the remaining four damaged (compared with actual British losses of two Blenheims lost and two damaged), for no losses.[14]

The greatest wartime successes achieved by CR.32s were in Italian East Africa.[7] Here, 410a and 411a Squadriglia CR.32s (which represented half of all the fighters operational in the Italian colony) destroyed a number of British and South African aircraft.[7] 410a Squadriglia managed to shoot down 14 enemy aircraft, including Bristol Blenheims and Hawker Hurricanes, before being disbanded.

The Fiats had their baptism of fire on 17 June, when CR. 32s of 411a Squadriglia flown by Tenente Aldo Meoli and Maresciallo Bossi attacked three South African Air Force Junkers Ju 86 bombers bound for Wavello, escorted by two Hurricanes of 1 SAAF Squadron. The Fiats shot down one of the Ju 86s and then pounced on the Hurricanes, shooting down the one flown by 2/Lt B.L. Griffiths, who was killed in the crash.[15] In the hands of a skillful pilot the CR.32 could still defeat faster, more powerful, better-armed monoplanes. On 23 February 1941, while he was attacking Makale airfield, flying a Hurricane, Maj Laurie Wilmot was bounced by ace Alberto Veronese in a Fiat biplane. Wilmot was forced to crash-land (and became a PoW). Soon after, Capt Andrew Duncan hit Veronese, who bailed out wounded.[16]

Fourteen CR.32s of 160° Gruppo and nine of 2° Gruppo from 6° Stormo saw action against Greece in the first weeks after the attack of 28 October 1940. Eight more from 163aa Squadriglia, based at Gadurrà airport on Rhodes, took part in the invasion of Crete. CR.32s of 3° Gruppo operated in Sardinia, but in the period of July–December 1940 their number fell from 28 to seven serviceable aircraft. The last front line CR.32 survived until mid-April 1941 when the "Freccias" were sent to the Scuola Caccia (Schools for fighter pilots). By 1942, the type was relegated to only night missions as newer fighters were put into service.

International use

China

The first international operator of the CR.32 was Chiang Kai-shek's for China, which ordered 16 (according to other sources 24) CR.32s of the first series in 1933. The aircraft mounted Vickers 7.7 mm machine guns instead of the Breda-SAFAT, electric headlights, and the cooling fins on the oil tank in the nose were removed. Additionally, some were equipped with radios. They were based at Nangahang airport, near Shanghai. Some officers of the Chinese high command disliked the Fiat, but Chinese pilots appreciated that the Italian biplanes in comparative tests proved superior to the American Curtiss Hawk and Boeing P-26. The Chinese Government did not order more CR.32s as it was difficult to import alcohol and benzole to mix with petrol for the engines. In May 1936, only six "Freccias" were still operational. In August 1937, the remaining CR.32s were used with some initial success in Shanghai against the invading Japanese.[9] By late 1937, when the Chinese capital at Nanjing fell, all CR.32s had been lost.[6]

Austria

In spring 1936, 45 CR.32s were ordered by Austria to equip Jagdgeschwader II at Wiener Neustadt. In March 1938, the Austrian units were absorbed into the Luftwaffe,[17] and, after a brief period, the 36 remaining aircraft were handed over to Hungary.[4]

Hungary

The Magyar Királyi Honvéd Légierő, the Royal Hungarian Air Force (MKHL), acquired a total of 76 CR.32's in 1935 and 1936. MKHL Fiat biplanes had their baptism of fire in 1939, during the short conflict with the new state of Slovakia. The CR.32s, with the red/white/green chevrons insignia, easily gained air superiority over the new Slovak Air Force which lost a few Avia B.534s and Letov S-328s.[18] During the short conflict against Yugoslavia, in April 1941, the MKHL lost three CR.32s [19] and, on 6 May 1941, the Hungarian Air Force still had 69 Fiat CR.32s on line.[20] In June 1941, when the kingdom of Hungary declared war on the Soviet Union, the CR.32 fighter equipped two of the units that supported the Hungarian Army on the Eastern Front: 1./I Group of 1st Fighter Wing, based in Szolnok, and 2./I Group, of 2nd Fighter Wing, based at Nyíregyháza.[21] On 29 June, the first aerial combat over Hungary took place, when seven Tupolev SB-2 bombers attacked the railway station at Csap and were intercepted by the Fiat CR.32s from 2/3 Fighter squadron. The Fiat biplanes shot down three of the raiders, for no loss to themselves.[22]

South America

In 1938, Venezuela acquired nine CR.32quaters (according to other sources, 10 aircraft.)[4] Modifications included a larger radiator to assist engine cooling in tropical climate conditions. The aircraft were delivered to Maracay in the second half of 1938 and equipped the 1° Regimiento de Aviación Militar del Venezuela. With five CR.32s still servicable, the aircraft were struck off charge in 1943.[6]

A small number, estimated at four,[4] went to Paraguay in 1938. Five CR.32quater fighters (registered 1-1, 1-3, 1-5, 1-7 and 1-9) were assigned to 1.a Escuadrilla de Caza of the Fuerzas Aéreas del Ejército Nacional del Paraguay. They did not arrive in time for military operations against Bolivia, but were in service for several years.[9]

Variants

The Regia Aeronautica ordered 1,080 CR.32s (including the two prototypes and 23 aircraft rebuilt by SCA factory in Guidonia, near Rome, plus 52 without military registry numbers for Hungary). With 100 more CR.32quaters licence-built in Spain (as the Hispano Ha. 132L Chirri), the total CR.32 production numbers range from 1,306 to 1,332 examples.

- CR.32

- Armed with twin 7.7 mm (.303 in) or 12.7 mm (.5 in) machine guns and powered by 447 kW (600 hp) Fiat A.30 R.A.bis engine. Delivered to the Regia Aeronautica between March 1934 and February 1936.

- CR.32bis

- Close-support fighter version armed with twin Breda-SAFAT Mod.1928Av. 7.7 mm (.303 in) (a common field modification was to discard the 7.7 mm armament to reduce weight) and twin 12.7 mm (.5 in) machine guns. Bomb racks with ability to carry 100 kg (220 lb) bombload possible: 1 × 100 kg (220 lb) or 2 × 50 kg (110 lb).

- CR.32ter

- Revised CR.32bis with many improved features.

- CR.32quater[23]

- Revised CR.32ter with reduced weight, added radio and max speed 356 km/h (221 mph) at 3,000 m (9,843 ft); 337 built for the Regia Aeronautica.

- CR.33

- 520 kW (700 hp) Fiat AC.33RC engine. Maximum speed 412 km/h (256 mph; 222 kn) at 3,500 m (11,500 ft).[24] Only three prototypes were built.

- CR.40

- One prototype powered by a Bristol Mercury IV radial engine.

- CR.40bis

- One prototype only.

- CR.41

- One prototype only.

- HA-132L Chirri

- Spanish version; 100 were built and 49 more of those used during the war were rebuilt. A total of 40 were transformed into two-seaters and kept in service as an aerobatic trainer till 1953.[25]

Operators

- Austrian Air Force received 45 CR.32bis aircraft[26]

- Luftwaffe operated former Austrian aircraft

- Paraguayan Air Arm ordered five aircraft in 1938.

- Venezuelan Air Force ordered nine aircraft in 1938.

Survivors

There are only two remaining CR.32: one is preserved at the Italian Air Force Museum, Vigna di Valle, and the other at the Museo del Aire de Cuatro Vientos, Madrid.

Specifications (CR.32)

General characteristics

- Crew: one

- Length: 7.47 m (24 ft 6 in)

- Wingspan: 9.5 m (31 ft 2.25 in)

- Height: 2.36 m (7 ft 9 in)

- Wing area: 22.1 m2 (237.88 ft2)

- Empty weight: 1,455 kg (3,210 lb)

- Loaded weight: 1,975 kg (4,350 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Fiat A30 RA-bis V12, 447 kW (600 hp)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 360 km/h (224 mph)

- Range: 781 km (485 mi)

- Service ceiling: 8,800 m (28,870 ft)

- Rate of climb: 9 m/s (1,822 ft/min)

Armament

- Guns: 2 × 7.7 mm (.303 in) or 12.7 mm (.5 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns

- Bombs: Up to 100 kg (220 lb)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fiat_C.R.32. |

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

- List of Interwar military aircraft

- List of aircraft of Italy in World War II

- List of aircraft of World War II

References

- Notes

- ↑ Mondey, D.: Axis Aircraft of WW II, 2002, p. 56

- ↑ Fiat CR.32

- ↑ Gunston 1988, p. 246.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mondey 2006, p. 55.

- ↑ Sgarlato 2005. pp. 10–14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 De Marchi, Italo and Enzo Maio (tavole). Macchi MC. 200 "Saetta: / Pietro Tonizzo Gianfranco Munerotto Fiat CR. 32. Modena: Stem Mucchi Editore, 1994.

- 1 2 3 4 Mondey 2006, p. 56.

- ↑ Mondey 2006, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Sgarlato, Nico. Fiat CR.42, CR.32 Gli ultimi biplani. Parma: Delta Editrice, 2005.

- ↑ Maslov 2010, p. 24.

- ↑ Shores 1983, p. 49.

- ↑ Shores 1983, p. 47.

- ↑ Shores, Massimello and Guest 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Shores, Massimello and Guest 2012, p. 23.

- ↑ Sutherland and Canwell 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Thomas 2003, p. 60.

- ↑ "After the Anschluss". www.ww2incolor.com. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, p. 120.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, p. 122.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, p. 125.

- ↑ Neulen 2000, p. 124.

- ↑ Green and Swanborough 1994, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ "Le monoplace de chasse Fiat "C.R.-33"". Les Ailes (777): 3. 7 May 1936.

- ↑ "One of the last "Chirris"?". www.ww2incolor.com. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ Haubner, F. Die Flugzeuge der Österreichischen Luftstreitkräfte vor 1938. Graz, Austria: H. Weishaupt Verlag, 1982.

- ↑ PRESTON, Paul. The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, Revolution & Revenge. Harper Perennial. London. 2006. p.117

- Bibliography

- Apostolo, Giorgio. Fiat CR 32 (Ali D'Italia 4). (in Italian/English). Torino, Italy: La Bancarella Aeronautica, 1996. No ISBN.

- Cattaneo, Gianni. The Fiat CR.32 (Aircraft in Profile Number 22). Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1965.

- "Connaissance de l'Histoir Hachette." Avions Militaires 1919–1939 Profils et Histoire (in French). Paris: 1979.

- De Marchi, Italo, Enzo Maio, Pietro Tonizzo and Gianfranco Munerotto. Macchi MC.200 "Saetta" – Fiat CR.32 (in Italian). Modena: Stem Mucchi, 1994.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Complete Book of Fighters. New York: Smithmark, 1994. ISBN 0-8317-3939-8.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. "The Facile Fiat... Rosatelli's Italian Fighter." Air Enthusiast Twenty-two, August–November 1983. Bromley, Kent, UK: Pilot Press Ltd., 1983.

- Gunston, Bill. The Illustrated Directory of Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Salamander Books Limited, 1988. ISBN 1-84065-092-3.

- Logoluso, Alfredo. Fiat CR.32 Aces of the Spanish Civil War. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2010. ISBN 978-1-84603-983-6.

- Maliza, Nicola. Il Fiat C.R. 32 – Poesia del Volo (in Italian). Rome: Edizioni dell'Ateneo & Bizzarri, 1981.

- Maslov, Mikhail A. Polikarpov I-15, I-16 and I-153. Oxford, Osprey Publishing, 2010. ISBN 978-1-84603-981-2.

- McCullough, Anson. "La Cucaracha." Airpower, Volume 28, No. 5, September 1998.

- Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II. London: Bounty Books, 2006. ISBN 0-7537-1460-4.

- Neulen, Hans Werner. In the Skies of Europe. Ramsbury, Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press, 2000. ISBN 1-86126-799-1.

- Punka, George. Fiat CR 32/CR 42 in Action (Aircraft Number 172). Carrollton, TX: Squadron/Signal, 2000. ISBN 0-89747-411-2.

- Sgarlato, Nico. Fiat CR.32 Freccia – CR.42 Falco (in Italian). Parma, Italy: Delta Editrice, 2005.

- Shores, Christopher. Air Aces. Greenwich, CT: Bison Books, 1983. ISBN 0-86124-104-5.

- Shores, Christopher, Giovanni Massimello and Russell Guest. A History of the Mediterranean Air War 1940–1945: Volume One: North Africa June 1940 – January 1942. London: Grub Street, 2012. ISBN 978-1-908117-07-6.

- Sutherland, Jon and Diane Canwell. Air War East Africa 1940–41. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Pen and Sword Aviation, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84415-816-4.

- Thomas, Andrew. Hurricane Aces 1941–45. Oxford, UK/New York: Osprey Publishing, 2003.ISBN 1-84176-610-0.

- Westburg, Peter. "Dogfight over Ruthenia." Airpower, Volume 13, No. 6, November 1983.