Fermi energy

The Fermi energy is a concept in quantum mechanics usually referring to the energy difference between the highest and lowest occupied single-particle states in a quantum system of non-interacting fermions at absolute zero temperature. In a Fermi gas, the lowest occupied state is taken to have zero kinetic energy, whereas in a metal, the lowest occupied state is typically taken to mean the bottom of the conduction band.

Confusingly, the term "Fermi energy" is often being used for referring to a different yet closely related concept, the Fermi level (also called electrochemical potential).[1] There are a few key differences between the Fermi level and Fermi energy, at least as they are used in this article:

- The Fermi energy is only defined at absolute zero, while the Fermi level is defined for any temperature.

- The Fermi energy is an energy difference (usually corresponding to a kinetic energy), whereas the Fermi level is a total energy level including kinetic energy and potential energy.

- The Fermi energy can only be defined for non-interacting fermions (where the potential energy or band edge is a static, well defined quantity), whereas the Fermi level (the electrochemical potential of an electron) remains well defined even in complex interacting systems, at thermodynamic equilibrium.

Since the Fermi level in a metal at absolute zero is the energy of the highest occupied single particle state, then the Fermi energy in a metal is the energy difference between the Fermi level and lowest occupied single-particle state, at zero-temperature.

Introduction

Context

In quantum mechanics, a group of particles known as fermions (for example, electrons, protons and neutrons) obey the Pauli exclusion principle. This states that two fermions cannot occupy the same quantum state. Since an idealized non-interacting Fermi gas can be analyzed in terms of single-particle stationary states, we can thus say that two fermions cannot occupy the same stationary state. These stationary states will typically be distinct in energy. To find the ground state of the whole system, we start with an empty system, and add particles one at a time, consecutively filling up the unoccupied stationary states with the lowest energy. When all the particles have been put in, the Fermi energy is the kinetic energy of the highest occupied state.

What this means is that even if we have extracted all possible energy from a Fermi gas by cooling it to near absolute zero temperature, the fermions are still moving around at a high speed. The fastest ones are moving at a velocity corresponding to a kinetic energy equal to the Fermi energy. This is the Fermi velocity. Only when the temperature exceeds the Fermi temperature do the electrons begin to move significantly faster than at absolute zero.

The Fermi energy is an important concept in the solid state physics of metals and superconductors. It is also a very important quantity in the physics of quantum liquids like low temperature helium (both normal and superfluid 3He), and it is quite important to nuclear physics and to understanding the stability of white dwarf stars against gravitational collapse.

Illustration of the concept for a one-dimensional square well

The one-dimensional infinite square well of length L is a model for a one-dimensional box. It is a standard model-system in quantum mechanics for which the solution for a single particle is well known. The levels are labeled by a single quantum number n and the energies are given by

where is the potential energy level inside the box.

Suppose now that instead of one particle in this box we have N particles in the box and that these particles are fermions with spin 1/2. Then not more than two particles can have the same energy, i.e., two particles can have the energy of , two other particles can have energy and so forth. The reason that two particles can have the same energy is that a particle can have a spin of 1/2 (spin up) or a spin of −1/2 (spin down), leading to two states for each energy level. In the configuration for which the total energy is lowest (the ground state), all the energy levels up to n = N/2 are occupied and all the higher levels are empty.

Defining the reference for the Fermi energy to be , the Fermi energy is therefore given by

for an odd number of electrons (N − 1), for an even number of electrons (N).

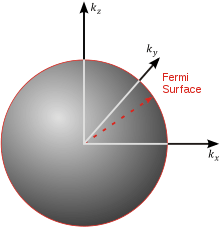

Three-dimensional case

The three-dimensional isotropic case is known as the Fermi sphere.

Let us now consider a three-dimensional cubical box that has a side length L (see infinite square well). This turns out to be a very good approximation for describing electrons in a metal. The states are now labeled by three quantum numbers nx, ny, and nz. The single particle energies are (where m is the mass of fermion (electron in this case))

- nx, ny, nz are positive integers. There are multiple states with the same energy, for example . Now let's put N non-interacting fermions of spin 1/2 into this box. To calculate the Fermi energy, we look at the case where N is large.

If we introduce a vector then each quantum state corresponds to a point in 'n-space' with energy

With denoting the square of the usual Euclidean length . The number of states with energy less than EF + E0 is equal to the number of states that lie within a sphere of radius in the region of n-space where nx, ny, nz are positive. In the ground state this number equals the number of fermions in the system.

the factor of two is once again because there are two spin states, the factor of 1/8 is because only 1/8 of the sphere lies in the region where all n are positive. We find

so the Fermi energy is given by

Which results in a relationship between the Fermi energy and the number of particles per volume (when we replace L2 with V2/3):

The total energy of a Fermi sphere of fermions is given by

Therefore, the average energy of an electron is given by:

Related quantities

Using this definition of Fermi Energy, various related quantities can be useful. The Fermi temperature is defined as:

where is the Boltzmann constant and the Fermi energy. The Fermi temperature can be thought of as the temperature at which thermal effects are comparable to quantum effects associated with Fermi statistics.[2] The Fermi temperature for a metal is a couple of orders of magnitude above room temperature.

Other quantities defined in this context are Fermi momentum and Fermi velocity:

where is the mass of the electron. These quantities are the momentum and group velocity, respectively, of a fermion at the Fermi surface. The Fermi momentum can also be described as , where is the radius of the Fermi sphere and is called the Fermi wave vector.[3]

These quantities are not well-defined in cases where the Fermi surface is non-spherical. In the case of the quadratic dispersion relations given above, they are given by:[4]

Arbitrary-dimensional case

Using a volume integral on dimensions, we can find the state density:

By then looking for the number of particles, we can extract the Fermi energy: To get:

where is the dimension for the internal Hilbert space. It is 2 in the case of spin

Typical Fermi energies

Metals

The number density of conduction electrons in metals ranges between approximately 1028 and 1029 electrons/m3, which is also the typical density of atoms in ordinary solid matter. This number density produces a Fermi energy of the order:

White dwarfs

Stars known as white dwarfs have mass comparable to our Sun, but have about a hundredth of its radius. The high densities mean that the electrons are no longer bound to single nuclei and instead form a degenerate electron gas. The number density of electrons in a white dwarf is of the order of 1036 electrons/m3. This means their Fermi energy is:

Nucleus

Another typical example is that of the particles in a nucleus of an atom. The radius of the nucleus is roughly:

- where A is the number of nucleons.

The number density of nucleons in a nucleus is therefore:

Now since the Fermi energy only applies to fermions of the same type, one must divide this density in two. This is because the presence of neutrons does not affect the Fermi energy of the protons in the nucleus, and vice versa.

So the Fermi energy of a nucleus is about:

The radius of the nucleus admits deviations around the value mentioned above, so a typical value for the Fermi energy is usually given as 38 MeV.

See also

- Fermi–Dirac statistics: the distribution of electrons over stationary states for a non-interacting fermions at non-zero temperature.

References

- ↑ The use of the term "Fermi energy" as synonymous with Fermi level (a.k.a. electrochemical potential) is widespread in semiconductor physics. For example: Electronics (fundamentals And Applications) by D. Chattopadhyay, Semiconductor Physics and Applications by Balkanski and Wallis.

- ↑ "Introduction to Quantum Statistical Thermodyamics" (PDF). Utah State University Physics. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ Ashcroft, Neil W.; Mermin, N. David (1976). Solid State Physics. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-083993-9.

- ↑ Fermi level and Fermi function, from HyperPhysics

- Kroemer, Herbert; Kittel, Charles (1980). Thermal Physics (2nd ed.). W. H. Freeman Company. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9.

- Table of Fermi energies, velocities, and temperatures for various elements.