Feminism in the United Kingdom

As in other countries, feminism in the United Kingdom seeks to establish political, social, and economic equality for women. The history of feminism in Britain dates to the very beginnings of feminism itself, as many of the earliest feminist writers and activists—such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Barbara Bodichon, and Lydia Becker—were British.

19th century

The advent of the reformist age during the 19th century meant that those invisible minorities or marginalised majorities were to find a catalyst and a microcosm in such new tendencies of reform. Robert Owen, while asking for "social reorganisation", was laying down the basis of a new reformational background. One of those movements that took advantage of such new spirit was the feminist movement. The stereotype of the Victorian gentle lady became unacceptable and even intolerable. The first organised movement for British women's suffrage was the Langham Place Circle of the 1850s, led by Barbara Bodichon (née Leigh-Smith) and Bessie Rayner Parkes. They also campaigned for improved female rights in the law, employment, education, and marriage.

Property owning women and widows had been allowed to vote in some local elections, but that ended in 1835. The Chartist Movement was a large-scale demand for suffrage—but it meant manhood suffrage. Upper-class women could exert a little backstage political influence in high society. However, in divorce cases, rich women lost control of their children.

Child custody

Before 1839 after divorce rich women lost control of their children as those children would continue in the family unit with the father, as head of the household, and who continued to be responsible for them. Caroline Norton was one such woman; her personal tragedy where she was denied access to her three sons after a divorce led her to a life of intense campaigning which successfully led to the passing of the Custody of Infants Act 1839 and introduced the Tender years doctrine for child custody arrangement.[1][2][3][4] The Act gave women, for the first time, a right to their children and gave some discretion to the judge in a child custody cases. Under the doctrine the Act also established a presumption of maternal custody for children under the age of seven years maintaining the responsibility for financial support to the father.[1] In 1873 due to additional pressure from women, the Parliament extended the presumption of maternal custody until a child reached sixteen.[5][6] The doctrine spread in many states of the world because of the British Empire.[3]

Divorce

Traditionally, poor people used desertion, and (for poor men) even the practice of selling wives in the market, as a substitute for divorce.[7] In Britain before 1857 wives were under the economic and legal control of their husbands, and divorce was almost impossible. It required a very expensive private act of Parliament costing perhaps £200, of the sort only the richest could possibly afford. It was very difficult to secure divorce on the grounds of adultery, desertion, or cruelty. The first key legislative victory came with the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857. It passed over the strenuous opposition of the highly traditional Church of England. The new law made divorce a civil affair of the courts, rather than a Church matter, with a new civil court in London handling all cases. The process was still quite expensive, at about £40, but now became feasible for the middle class. A woman who obtained a judicial separation took the status of a feme sole, with full control of her own civil rights. Additional amendments came in 1878, which allowed for separations handled by local justices of the peace. The Church of England blocked further reforms until the final breakthrough came with the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973.[8][9]

Protection for rich and poor women

A series of four laws called the Married Women's Property Act passed Parliament from 1870 to 1882 that effectively removed the restrictions that kept wealthy married women from controlling their own property. They now had practically equal status with their husbands, and a status superior to women anywhere else in Europe.[10][11][12] Working class women were protected by a series of laws passed on the assumption that they (like children) did not have full bargaining power and needed protection by the government.[13]

Prostitution

Bullough argues that prostitution in 18th-century Britain was a convenience to men of all social statuses, and economic necessity for many poor women, and was tolerated by society. The evangelical movement of the nineteenth century denounced the prostitutes and their clients as sinners, and denounced society for tolerating it.[14] Prostitution, according to the values of the Victorian middle-class, was a horrible evil, for the young women, for the men, and for all of society. Parliament in the 1860s in the Contagious Diseases Acts ("CD") adopted the French system of licensed prostitution. The "regulationist policy" was to isolate, segregate, and control prostitution. The main goal was to protect working men, soldiers and sailors near ports and army bases from catching venereal disease. Young women officially became prostitutes and were trapped for life in the system. After a nationwide crusade led by Josephine Butler and the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, Parliament repealed the acts and ended legalised prostitution. Butler became a sort of saviour to the girls she helped free. The age of consent for young women was raised from 12 to 16, undercutting the supply of young prostitutes who were in highest demand. The new moral code meant that respectable men dared not be caught.[15][16][17][18]

Careers

Ambitious middle-class women faced enormous challenges and the goals of entering suitable careers, such as nursing, teaching, law and medicine. The loftier their ambition, the greater the challenge. Physicians kept tightly shut the door to medicine; there were a few places for woman as lawyers, but none as clerics.[19] White collar business opportunities outside family-owned shops were few until clerical positions opened in the 20th century. Florence Nightingale demonstrated the necessity of professional nursing and warfare, and set up an educational system that tracked women into that field in the second half of the nineteenth century. Teaching was not quite as easy to break into, but the low salaries were less of the barrier to the single woman then to the married man. By the late 1860s a number of schools were preparing women for careers as governesses or teachers. The census reported in 1851 that 70,000 women in England and Wales were teachers, compared to the 170,000 who comprised three-fourths of all teachers in 1901.[20][21] The great majority came from lower middle class origins.[22] The National Union of Women Teachers (NUWT) originated in the early 20th century inside the male-controlled National Union of Teachers (NUT). It demanded equal pay with male teachers, and eventually broke away.[23] Oxford and Cambridge minimized the role of women, allowing small all-female colleges operate. However the new redbrick universities and the other major cities were open to women.[24]

Medicine was greatest challenge, with the most systematic resistance by the physicians, and the fewest women breaking through. One route to entry was to go to the United States where there were suitable schools for women as early as 1850. Britain was the last major country to train women physicians, so 80 to 90% of the British women came to America for their medical degrees. Edinburgh University admitted a few women in 1869, then reversed itself in 1873, leaving a strong negative reaction among British medical educators. The first separate school for women physicians opened in London in 1874 to a handful of students. Scotland was more open. Coeducation had to wait until the World War.[25]

By the end of the nineteenth century women had secured equality of status in most spheres – except of course for the vote and the holding of office.

20th century

The early 20th century, the Edwardian era, saw a loosening of Victorian rigidity and complacency: women had more employment opportunities and were more active. Many served worldwide in the British Empire or in Protestant missionary societies.

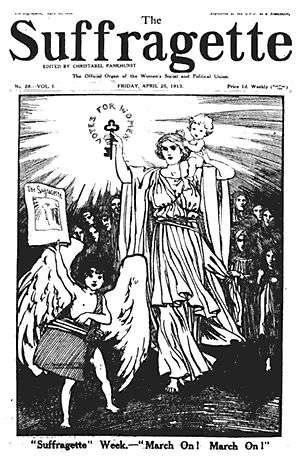

The charismatic and dictatorial Pankhursts formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903. As Emmline Pankhurst put it, they viewed votes for women no longer as "a right, but as a desperate necessity".[26] Women had the vote in Australia, New Zealand and some of the American states. While WSPU was the most visible suffrage group, it was only one of many, such as the Women's Freedom League and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett.

In 1906, the Daily Mail first coined the term "suffragettes" as a form of ridicule, but the term was quickly embraced in Britain to describe militant tactics. The term became visible in distinctive green, purple, and white emblems, and the Artists' Suffrage League's dramatic graphics. Feminists learned to exploit photography and the media, and left a vivid visual record including images such as the 1914 photograph of Emmeline.[27] Violence separated the moderates from the radicals led by the Pankhursts. The radicals themselves split; Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst expelled Sylvia Pankhurst for insubordination and she formed her own group that was left-wing and oriented to broader issues affecting working class women.[28]

The radical protests slowly became more violent, and included heckling, banging on doors, smashing shop windows, and arson. Emily Davison, a WSPU member, unexpectedly ran onto the track during the 1913 Epsom Derby and died under the King's horse. These tactics produced mixed results of sympathy and alienation. As many protesters were imprisoned and went on hunger-strike, the Liberal government was left with an embarrassing situation. From these political actions, the suffragists successfully created publicity around their institutional discrimination and sexism. Historians generally argue that the first stage of the militant suffragette movement under the Pankhursts in 1906 had a dramatic mobilizing effect on the suffrage movement. Women were thrilled and supportive of an actual revolt in the streets; the membership of the militant WSPU and the older NUWSS overlapped and was mutually supportive. However a system of publicity, Ensor argues, had to continue to escalate to maintain its high visibility in the media. The hunger strikes and force-feeding did that. However the Pankhursts refused any advice and escalated their tactics. They turned to systematic disruption of Liberal Party meetings as well as physical violence in terms of damaging public buildings and arson. This went too far, as the overwhelming majority of suffragists pulled back and refused to follow because they could no longer defend the tactics. Shey increasingly repudiated the suffragettes as an obstacle to achieving suffrage, saying the militant suffragettes were now aiding the antis, and many historians agree. Searle says the methods of the suffragettes did succeed in damaging the Liberal party but failed to advance the cause of woman suffrage. When the Pankhursts decided to stop the militancy at the start of the war, and enthusiastically support the war effort, the movement split and their leadership role ended. Suffrage did come four years later, but the feminist movement in Britain permanently abandoned the militant tactics that had made the suffragettes famous.[29][30]

The First World War advanced the feminist cause, as women's sacrifices and paid employment were much appreciated. Prime Minister David Lloyd George was clear about how important the women were:

It would have been utterly impossible for us to have waged a successful war had it not been for the skill and ardour, enthusiasm and industry which the women of this country have thrown into the war.[31]

The militant suffragette movement was suspended during the war and never resumed. British society credited the new patriotic roles women played as earning them the vote in 1918.[32] However, British historians no longer emphasize the granting of woman suffrage as a reward for women's participation in war work. Pugh (1974) argues that enfranchising soldiers primarily and women secondarily was decided by senior politicians in 1916. In the absence of major women's groups demanding for equal suffrage, the government's conference recommended limited, age-restricted women's suffrage. The suffragettes had been weakened, Pugh argues, by repeated failures before 1914 and by the disorganising effects of war mobilization; therefore they quietly accepted these restrictions, which were approved in 1918 by a majority of the War Ministry and each political party in Parliament.[33] More generally, Searle (2004) argues that the British debate was essentially over by the 1890s, and that granting the suffrage in 1918 was mostly a byproduct of giving the vote to male soldiers. Women in Britain finally achieved suffrage on the same terms as men in 1928.[34]

There was a relaxing of clothing restrictions; by 1920 there was negative talk about young women called "flappers" flaunting their sexuality.[35]

Electoral reform

The United Kingdom's Representation of the People Act 1918[36] gave near-universal suffrage to men, and suffrage to women over 30. The Representation of the People Act 1928 extended equal suffrage to both men and women. It also shifted the socioeconomic makeup of the electorate towards the working class, favouring the Labour Party, which was more sympathetic to women's issues.[37] The 1918 election gave Labour the most seats in the house to date. The electoral reforms also allowed women to run for Parliament. Christabel Pankhurst narrowly failed to win a seat in 1918, but in 1919 and 1920, both Lady Astor and Margaret Wintringham won seats for the Conservatives and Liberals respectively by succeeding their husband's seats. Labour swept to power in 1924. Constance Markievicz (Sinn Féin) was the first woman elected in Ireland in 1918, but as an Irish nationalist, refused to take her seat. Astor's proposal to form a women's party in 1929 was unsuccessful. Women gained considerable electoral experience over the next few years as a series of minority governments ensured almost annual elections, but there were 12 women in Parliament by 1940. Close affiliation with Labour also proved to be a problem for the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC), which had little support in the Conservative party. However, their persistence with Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin was rewarded with the passage of the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928.[38]

Social reform

The political change did not immediately change social circumstances. With the economic recession, women were the most vulnerable sector of the workforce. Some women who held jobs prior to the war were obliged to forfeit them to returning soldiers, and others were excessed. With limited franchise, the UK National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) pivoted into a new organisation, the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship (NUSEC),[39] which still advocated for equality in franchise, but extended its scope to examine equality in social and economic areas. Legislative reform was sought for discriminatory laws (e.g., family law and prostitution) and over the differences between equality and equity, the accommodations that would allow women to overcome barriers to fulfillment (known in later years as the "equality vs. difference conundrum").[40] Eleanor Rathbone, who became a MP in 1929, succeeded Millicent Garrett as president of NUSEC in 1919. She expressed the critical need for consideration of difference in gender relationships as "what women need to fulfill the potentialities of their own natures".[41] The 1924 Labour government's social reforms created a formal split, as a splinter group of strict egalitarians formed the Open Door Council in May 1926.[42] This eventually became an international movement, and continued until 1965. Other important social legislation of this period included the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 (which opened professions to women), and the Matrimonial Causes Act 1923. In 1932, NUSEC separated advocacy from education, and continued the former activities as the National Council for Equal Citizenship and the latter as the Townswomen's Guild. The council continued until the end of the Second World War.[43]

In 1921, Margaret Mackworth (Lady Rhondda) founded the Six Point Group,[44] which included Rebecca West. As a political lobby group it aimed at political, occupational, moral, social, economic and legal equality. Thus it was ideologically allied with the Open Door Council, rather than National Council. It also lobbied at an international level, such as the League of Nations, and continued its work till 1983. In retrospect both ideological groups were influential in advancing women's rights in their own way. Despite women being admitted to the House of Commons from 1918, Mackworth, a Viscountess in her own right, spent a lifetime fighting to take her seat in the House of Lords against bitter opposition, a battle which only achieved its goal in the year of her death (1958). This revealed the weaknesses of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act. Mackworth also founded Time and Tide which became the group's journal, and to which West, Virginia Woolf, Rose Macaulay and many others contributed. A number of other women's periodicals also appeared in the 1920s, including Woman and Home, and Good Housekeeping, but whose content reflect very different aspirations. In 1925 Rebecca West wrote in Time and Tide something that reflected not only the movement's need to redefine itself post suffrage, but a continual need for re-examination of goals. "When those of our army whose voices are inclined to coolly tell us that the day of sex-antagonism is over and henceforth we have only to advance hand in hand with the male, I do not believe it."[45]

Reproductive rights

Annie Besant had been tried in 1877 for publishing Charles Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy,[46] a work on family planning, under the Obscene Publications Act 1857.[47][48] Knowlton had previously been convicted in the United States. She and her colleague Charles Bradlaugh were convicted but acquitted on appeal, the subsequent publicity resulting in a decline in the birth rate.[49][50] Not discouraged in the slightest, Besant followed this with The Law of Population.[51]

1950s

1950s Britain has traditionally been regarded as a bleak period for militant feminism. In the aftermath of World War II, a new emphasis was placed on companionate marriage and the nuclear family as a foundation of the new welfare state.[52][53]

In 1951, the proportion of adult women who were (or had been) married was 75%; more specifically, 84.8% of women between the ages of 45 and 49 were married.[54] At that time: “marriage was more popular than ever before.”[55] In 1953, a popular book of advice for women states: “A happy marriage may be seen, not as a holy state or something to which a few may luckily attain, but rather as the best course, the simplest, and the easiest way of life for us all”.[56]

While at the end of the war, childcare facilities were closed and assistance for working women became limited, the social reforms implemented by the new welfare state included family allowances meant to subsidize families, that is, to support women in the “capacity as wife and mother.”[53] Sue Bruley argues that “the progressive vision of the New Britain of 1945 was flawed by a fundamentally conservative view of women”.[57]

Women's commitment to companionate marriage was echoed by the popular media: films, radio and popular women's magazines. In the 1950s, women's magazines had considerable influence on forming opinion in all walks of life, including the attitude to women’s employment.

Nevertheless, 1950s Britain saw several strides towards the parity of women, such as equal pay for teachers (1952) and for men and women in the civil service (1954), thanks to activists like Edith Summerskill, who fought for women’s causes both in parliament and in the traditional non-party pressure groups throughout the 1950s.[58] Barbara Caine argues: “Ironically here, as with the vote, success was sometimes the worst enemy of organised feminism, as the achievement of each goal brought to an end the campaign which had been organised around it, leaving nothing in its place.”[59]

Feminist writers of that period, such as Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein, started to allow for the possibility that women should be able to combine home with outside employment. 1950s’ form of feminism is often derogatorily termed “welfare feminism.”[60] Indeed, many activists went to great length to stress that their position was that of ‘reasonable modern feminism,’ which accepted sexual diversity, and sought to establish what women’s social contribution was rather than emphasizing equality or the similarity of the sexes. Feminism in 1950s England was strongly connected to social responsibility and involved the well-being of society as a whole. This often came at the cost of the liberation and personal fulfillment of self-declared feminists. Even those women who regarded themselves as feminists strongly endorsed prevailing ideas about the primacy of children’s needs, as advocated, for example, by John Bowlby the head of the Children's Department at the Tavistock Clinic, who published extensively throughout the 1950s and by Donald Winnicott who promoted through radio broadcasts and in the press the idea of the home as a private emotional world in which mother and child are bound to each other and in which the mother has control and finds freedom to fulfill herself.[61]

When Margaret Thatcher died the then Leader of the Opposition, Ed Miliband paid tribute to her as "the first woman Prime Minister".[62] However Thatcher received scant credit from feminists for breaking the ultimate glass ceiling, because she herself avoided feminism, and expressed an intensely masculine style.[63][64]

21st century

Since 2007, Harriet Harman has been Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, the UK's current opposition party. Traditionally, being Deputy Leader has ensured the cabinet role of Deputy Prime Minister. However, Gordon Brown announced that he would not have a Deputy Prime Minister, much to the consternation of feminists,[65] particularly with suggestions that privately Brown considered Jack Straw to be de facto deputy prime minister[66] and thus bypassing Harman. With Harman's cabinet post of Leader of the House of Commons, Brown allowed her to chair Prime Minister's Questions when he was out of the country. Harman also held the post Minister for Women and Equality. In April 2012 after being sexually harassed on London public transport English journalist Laura Bates founded the Everyday Sexism Project, a website which documents everyday examples of sexism experienced by contributors from around the world. The site quickly became successful and a book compilation of submissions from the project was published in 2014. In 2013, the first oral history archive of the United Kingdom women’s liberation movement (titled Sisterhood and After) was launched by the British Library.[67]

Timeline

- 1818: Jeremy Bentham advocates female suffrage in his book A Plan for Parliamentary Reform

- 1832: Great Reform Act – confirmed the exclusion of women from the electorate.

- 1839: Custody of Infants Act gives separated mothers the right to apply for custody of small children.[68]

- 1851: The Sheffield Female Political Association is founded and submits a petition calling for women's suffrage to the House of Lords.

- 1864: The first Contagious Disease Act is passed in England, to control venereal disease by having women believed to be prostitutes be locked away in hospitals for examination and treatment. When information broke to the general public about the shocking stories of brutality and vice in these hospitals, Josephine Butler launched a campaign to get them repealed. Many have since argued that Butler's campaign destroyed the conspiracy of silence around sexuality and forced women to act in protection of others of their gender.[69]

- 1857: Matrimonial Causes Act allows for easier divorce through a Divorce Court based in London. Divorce remains too expensive for the working class.[68]

- 1865: John Stuart Mill elected as an MP showing direct support for women's suffrage.

- 1867: Second Reform Act – Male franchise extended to 2.5 million; no mention of women

- 1870: Married Women's Property Act the first in a series of laws 1870-1882 that allow married women to control their own property.[70]

- 1878: Magistrates courts given the authority to grant separation and maintenance orders to wives of abusive husbands; much cheaper than divorce.[68]

- 1883: Conservative Primrose League formed.

- 1884: Third Reform Act – Male electorate doubled to 5 million

- 1889: Women's Franchise League established.

- 1894: Local Government Act; women who owned property can vote in local elections, become Poor Law Guardians, serve on School Boards

- 1894: The publication of C.C. Stopes's British Freewomen, staple reading for the suffrage movement for decades.[71]

- 1897: National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies NUWSS formed (led by Millicent Fawcett).[72]

- 1903: Women's Social and Political Union WSPU is formed (under tight control of Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters)[28]

- 1904: WPSU Militancy begins.

- February 1907: NUWSS "Mud March" – largest open air demonstration ever held (at that point) – over 3000 women took part. In this year, women were admitted to the register to vote in and stand for election to principal local authorities.

- 1907: The Artists' Suffrage League founded

- 1907: The Women's Freedom League founded

- 1908: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, a member of the small municipal borough of Aldeburgh, Suffolk, was selected as mayor of that town, the first woman to so serve.

- 1905, 1908, 1913: Three phases of WSPU militancy (Civil Disobedience; Destruction of Public Property; Arson/Bombings);

- 1909 The Women's Tax Resistance League founded

- September 1909: Force feeding introduced to WSPU hunger strikers in English prisons

- February 1910: Cross-Party Conciliation Committee (54 MPs). Conciliation Bill (that would enfranchise women) passed its 2nd reading by a majority of 109 but Prime Minister Asquith refused to give it more parliamentary time

- November 1910: Asquith changes Bill to enfranchise more men instead of women

- October 1912: George Lansbury, Labour MP, resigned his seat in support of women's suffrage

- February 1913: David Lloyd George's house burned down by WSPU[73] (despite his support for women's suffrage).

- April 1913: Cat and Mouse Act passed, allowing hunger-striking prisoners to be released when their health was threatened and then re-arrested when they had recovered

- 4 June 1913: Emily Davison of WSPU jumped in front of, and was subsequently trampled and killed by, the King’s Horse at the Epsom Derby.

- 13 March 1914: Mary Richardson of WSPU slashed the Rokeby Venus painted by Diego Velázquez in the National Gallery with an axe, protesting that she was maiming a beautiful woman just as the government was maiming Emmeline Pankhurst with force feeding

- 4 August 1914: First World War declared in Britain. WSPU activity immediately ceased. NUWSS activity continued peacefully – the Birmingham branch of the organisation continued to lobby Parliament and write letters to MPs.

- 1918: The Representation of the People Act of 1918 enfranchised women over the age of 30 who were either a member or married to a member of the Local Government Register. About 8.4 million women gained the vote.

- November 1918: the Eligibility of Women Act was passed, allowing women to be elected into Parliament.[74]

- 1928: Women received the vote on the same terms as men (over the age of 21) as a result of the Representation of the People Act 1928.

See also

- First-wave feminism

- History of feminism

- History of women in the United Kingdom

- New Left

- New social movements

- Post-war Britain

- Pro-life feminism

- Second-wave feminism

- Sex-positive feminism

- The left and feminism

- The Women's Library (London)

- Third-wave feminism

- Timeline of women's rights (other than voting)

- Mary Wollstonecraft

Further reading

- Bartley, Paula (2000). Prostitution: prevention and reform in England, 1860-1914. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415214575.

- Brittain, Vera (1960). The women at Oxford. London: George G. Harrap. OCLC 252829150.

- Bruley, Sue, ed. (1999). Women in Britain since 1900. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780333618394.

- Bullough, Vern L. (1985). "Prostitution and reform in eighteenth-century England". Eighteenth-Century Life. 9 (3): 61–74.

- Also available as: Bullough, Vera L. (1987), "Prostitution and reform in eighteenth-century England", in Maccubbin, Robert P., ed. (1987). Tis nature's fault: unauthorized sexuality during the Enlightenment. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–74. ISBN 9780521347686.

- Caine, Barbara, ed. (1997). English feminism, 1780-1980. Oxford, England New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9786610767090.

- Caine, Barbara (1992). Victorian feminists. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198204336.

- Ferguson, Marjorie (1983). Forever feminine: women's magazines and the cult of femininity. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9780435823023.

- Feurer, Rosemary (Winter 1988). "The meaning of "sisterhood": the British Women's Movement and protective labor legislation, 1870-1900". Victorian Studies. Indiana University Press. 31 (2): 233–260. JSTOR 3827971.

- Finch, Janet; Summerfield, Penny (1991), "Social reconstruction and the emergence of companionate marriage, 1945–59", in Clark, David, Marriage, domestic life, and social change: writings for Jacqueline Burgoyne, 1944-88, London New York, New York: Routledge, pp. 7–32, ISBN 9780415032469.

- Harrison, Brian (1978). Separate spheres: the opposition to women's suffrage in Britain. New York: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 9780841903852.

- Lewis, Jane (1983). Women's welfare: women's rights. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 9780709941002.

- Lewis, Jane (1990), "Myrdal, Klein, Women’s Two Roles and Postwar Feminism 1945–1960", in Smith, Harold L., British feminism in the Twentieth Century, Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, pp. 167–188, ISBN 9780870237058.

- Lewis, Jane, ed. (1984). Women in England, 1870-1950: sexual divisions and social change. Brighton, Sussex Bloomington: Wheatsheaf Books Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780710801869.

- Myrdal, Alva; Klein, Viola (2001). Women's two roles: home and work. London: Routledge & Kegan. ISBN 9780415176576.

- Phillips, Melanie (2004). The ascent of woman: a history of the suffragette movement. London: Abacus. ISBN 9780349116600.

- Pierce, Rachel M. (July 1963). "Marriage in the Fifties". The Sociological Review. Cambridge Journals. 11 (2): 215–240. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.1963.tb01232.x.

- Pugh, Martin (1990), "Domesticity and the decline of feminism 1930–1950", in Smith, Harold L., British feminism in the Twentieth Century, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, pp. 144–162, ISBN 9780870237058.

- Pugh, Martin (2000). Women and the women's movement in Britain, 1914-1959. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312234911.

- Pugh, Martin D. (October 1974). "Politicians and the woman's vote 1914–1918". History. Wiley. 59 (197): 358–374. JSTOR 24409414. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1974.tb02222.x.

- Raz, Orna (2007). Social dimensions in the novels of Barbara Pym, 1949-1963 : the Writer as Hidden Observer. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 9780773453876.

- Shanley, Mary Lyndon (Autumn 1986). "Suffrage, protective labor legislation, and Married Women's Property Laws in England". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. Chicago Journals. 12 (1): 62–77. JSTOR 3174357. doi:10.1086/494297.

- Smith, Harold L., ed. (1990). British feminism in the Twentieth Century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 9780870237058.

- Spencer, Stephanie (2005). Gender, work and education in Britain in the 1950s. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403938169.

- Strachey, Ray; Strachey, Barbara (1978). The cause: a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain. London: Virago. ISBN 9780860680420.

- Tamboukou, Maria (2000). "Of Other Spaces: Women's colleges at the turn of the nineteenth century in the UK". Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography. Taylor and Francis. 7 (3): 247–263. doi:10.1080/713668873.

- Whiteman, Phyllis, ed. (1953). Speaking as a woman. London: Chapman & Hall. OCLC 712429455.</ref>

References

- 1 2 Wroath, John (2006). Until they are seven: the origins of women's legal rights. Winchester England: Waterside Press. ISBN 9781872870571.

- ↑ Mitchell, L. G. (1997). Lord Melbourne, 1779-1848. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198205920.

- 1 2 Perkins, Jane Gray (2013) [1909]. Life of the honourable Mrs. Norton. London: Theclassics Us. ISBN 9781230408378.

- ↑ Hilton, Boyd (2006), "Ruling ideologies: the status of women and ideas about gender", in Hilton, Boyd, A mad, bad, and dangerous people?: England, 1783-1846, Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 353–355, ISBN 9780198228301.

- ↑ "Tender Years Doctrine". legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com. The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ Katz, Sanford N. (1992). ""That they may thrive" goal of child custody: reflections on the apparent erosion of the tender years presumption and the emergence of the primary caretaker presumptions". Journal of Contemporary Health Law and Policy. Columbus School of Law, The Catholic University of America. 8 (1).

- ↑ Stone, Lawrence (1990), "Desertion, elopement, and wife-sale", in Stone, Lawrence, Road to divorce: England 1530-1987, Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 143–148, ISBN 9780198226512. Available online.

- ↑ Stone, Lawrence, ed. (1990). Road to divorce: England 1530-1987. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198226512.

- ↑ Halévy, Élie (1934), A history of the English people, London: Ernest Benn, OCLC 504342781

- ↑ Halévy, Élie (1934). A history of the English people. London: Ernest Benn. pp. 495–496. OCLC 504342781.

- ↑ Griffin, Ben (March 2003). "Class, gender, and liberalism in Parliament, 1868–1882: the case of the Married Women's Property Acts". The Historical Journal. Cambridge Journals. 46 (1): 59–87. doi:10.1017/S0018246X02002844.

- ↑ Lyndon Shanley, Mary (Autumn 1986). "Suffrage, protective labor legislation, and Married Women's Property Laws in England". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. Chicago Journals. 12 (1): 62–77. JSTOR 3174357. doi:10.1086/494297.

- ↑ Feurer, Rosemary (Winter 1988). "The meaning of "sisterhood": the British Women's Movement and protective labor legislation, 1870-1900". Victorian Studies. Indiana University Press. 31 (2): 233–260. JSTOR 3827971.

- ↑ Bullough, Vern L. (1985). "Prostitution and reform in eighteenth-century England". Eighteenth-Century Life. 9 (3): 61–74.

- Also available as: Bullough, Vera L. (1987), "Prostitution and reform in eighteenth-century England", in Maccubbin, Robert P., ed. (1987). Tis nature's fault: unauthorized sexuality during the Enlightenment. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–74. ISBN 9780521347686.

- ↑ Halévy, Élie (1934). A history of the English people. London: Ernest Benn. pp. 498–500. OCLC 504342781.

- ↑ Strachey, Ray; Strachey, Barbara (1978). The cause: a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain. London: Virago. pp. 187–222. ISBN 9780860680420.

- ↑ Bartley, Paula (2000). Prostitution: prevention and reform in England, 1860-1914. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415214575.

- ↑ Smith, F.B. (August 1990). "The Contagious Diseases Acts reconsidered". Social History of Medicine. Oxford Journals. 3 (2): 197–215. PMID 11622578. doi:10.1093/shm/3.2.197.

- ↑ Halévy, Élie (1934). A history of the English people. London: Ernest Benn. pp. 500–506. OCLC 504342781.

- ↑ Halévy, Élie (1934). A history of the English people. London: Ernest Benn. p. 500. OCLC 504342781.

- ↑ Copelman, Dina (2014). London's women teachers: gender, class and feminism, 1870-1930. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415867528.

- ↑ Coppock, David A. (1997). "Respectability as a prerequisite of moral character: the social and occupational mobility of pupil teachers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries". History of Education. Taylor and Francis. 26 (2): 165–186. doi:10.1080/0046760970260203.

- ↑ Owen, Patricia (1988). "'Who would be free, herself must strike the blow'". History of Education. Taylor and Francis. 17 (1): 83–99. doi:10.1080/0046760880170106.

- ↑ Tamboukou, Maria (2000). "Of Other Spaces: Women's colleges at the turn of the nineteenth century in the UK". Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography. Taylor and Francis. 7 (3): 247–263. doi:10.1080/713668873.

- ↑ Bonner, Thomas Neville (1995), "The fight for coeducation in Britain", in Bonner, Thomas Neville, To the ends of the earth: women's search for education in medicine, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, pp. 120–137, ISBN 9780674893047.

- ↑ Purvis, Jane (2003), "Socialist and public representative", in Purvis, June, ed. (2003). Emmeline Pankhurst: a biography. London: Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 9781280051128.

- ↑ Broom, Christina (1989). Atkinson, Diane, ed. Mrs Broom's suffragette photographs: photographs by Christina Bloom, 1908 to 1913. London: Dirk Nishen Publishing. ISBN 9781853781100.

- 1 2 Mitchell, David J. (1967). The fighting Pankhursts: a study in tenacity. London: J. Cape. OCLC 947754857.

- ↑ Ensor, Robert C.K. England: 1870-1914. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 389–399. OCLC 24731395.

- ↑ Searle, G. R. (2004), "The years of 'crisis', 1908-1914: The woman's revolt", in Searle, G. R., A new England?: Peace and war, 1886-1918, Oxford New York: Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, pp. 456–470, ISBN 9780198207146. Quote pp. 468.

- ↑ Whitfield, Bob (2001), "How did the First World War affect the campaign for women's sufferage?", in Whitfield, Bob, ed. (2001). The extension of the franchise, 1832-1931. Oxford: Heinemann Educational. p. 167. ISBN 9780435327170.

- ↑ Taylor, A.J.P. (1965). English History, 1914-1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 29, 94. OCLC 185566309.

- ↑ Pugh, Martin D. (October 1974). "Politicians and the woman's vote 1914–1918". History. Wiley. 59 (197): 358–374. JSTOR 24409414. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1974.tb02222.x.

- ↑ Searle, G. R. (2004), "War and the reshaping of identities: gender and generation", in Searle, G. R., A new England?: Peace and war, 1886-1918, Oxford New York: Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, p. 791, ISBN 9780198207146.

- ↑ Langhamer, Claire (2000), "'Stepping out with the young set': youthful freedom and independence", in Langhamer, Claire, ed. (2000). Women's leisure in England, 1920-60. Manchester New York: Manchester University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780719057373.

- ↑ "Representation of the People Act 1918". parliament.uk. Parliament of the United Kingdom.

- ↑ Smyth, James J. (2000). Labour in Glasgow, 1896-1936: socialism, suffrage, sectarianism. East Linton, East Lothian, Scotland: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 9781862321373.

- ↑ Close, David H. (December 1977). "The collapse of resistance to democracy: conservatives, adult suffrage, and Second Chamber reform, 1911–1928". The Historical Journal. Cambridge Journals. 20 (4): 893–918. JSTOR 2638413. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00011456.

- ↑ "Strand 2: Women's Suffrage Societies (2NSE Records of the National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship)". twl-calm.library.lse.ac.uk. The Women's Library @ London School of Economics.

- ↑ Offen, Karen (Summer 1995). "Women in the western world". Journal of Women's Studies. Johns Hopkins University Press. 7 (2): 145–151. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0359.

- ↑ Wayne, Tiffany K. (2011), ""The Old and the New Feminism" (1925) by Eleanor Rathbone", in Wayne, Tiffany K., ed. (2011). Feminist writings from ancient times to the modern world: a global sourcebook and history. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. pp. 484–485. ISBN 9780313345814.

- ↑ "Strand 5: (5ODC Campaigning Organisations Records of the Open Door Council)". twl-calm.library.lse.ac.uk. The Women's Library @ London School of Economics.

- ↑ Pedersen, Susan (2004). Eleanor Rathbone and the politics of conscience. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300102451.

- ↑ "Strand 5: (5SPG Records of the Six Point Group (including the Papers of Hazel Hunkins-Hallinan))". twl-calm.library.lse.ac.uk. The Women's Library @ London School of Economics.

- ↑ Walters, Margaret (2005). "Early 20th-century feminism". In Walters, Margaret, ed. (2005). Feminism: a very short introduction. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9780192805102.

- ↑ Knowlton, Charles (October 1891) [1840]. Besant, Annie; Bradlaugh, Charles, eds. Fruits of philosophy: a treatise on the population question. San Francisco: Reader's Library. OCLC 626706770. View original copy.

- See also: Langer, William L. (Spring 1975). "The origins of the birth control movement in England in the early nineteenth century". Journal of Interdisciplinary History, special issue: The History of the Family, II. MIT Press. 5 (4): 669–686. JSTOR 202864. doi:10.2307/202864.

- ↑ Chandrasekhar, Sripati (1981). "A dirty filthy book": The writings of Charles Knowlton and Annie Besant on reproductive physiology and birth control, and an account of the Bradlaugh-Besant trial. Berkeley: University of California Press. OCLC 812924875.

- ↑ Manvell, Roger (1976). The trial of Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh. London: Elek Pemberton. ISBN 9780236400058.

- ↑ Banks, J.A.; Banks, Olive (July 1954). "The Bradlaugh-Besant trial and the english newspapers". Population Studies: A Journal of Demography. Taylor and Francis. 8 (1): 22–34. JSTOR 2172561. doi:10.1080/00324728.1954.10415306.

- ↑ Balaram, P. (10 August 2003). "Population". Current Science. Current Science Association (India). 85 (3): 233–234. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016.

- ↑ Besant, Annie (1877). The law of population: its consequences, and its bearing upon human conduct and morals. London: Freethought Publishing Company. OCLC 81167553.

- ↑ Ward, Paul (2004), "Gender and national identity: Gender, 'race' and home in post-war Britain", in Ward, Paul, Britishness since 1870, London New York: Routledge, p. 50, ISBN 9780415220170.

- 1 2 Pugh, Martin (1990), "Domesticity and the decline of feminism 1930–1950", in Smith, Harold L., British feminism in the Twentieth Century, Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, p. 158, ISBN 9780870237058.

- ↑ Lewis, Jane (1984), "Patterns of marriage and motherhood", in Lewis, Jane, Women in England, 1870-1950: sexual divisions and social change, Brighton, Sussex Bloomington: Wheatsheaf Books Indiana University Press, p. 3, ISBN 9780710801869.

- ↑ Bruley, Sue (1999), "From austerity to prosperity and the pill: the Post-War years, 1945–c.1968", in Bruley, Sue, Women in Britain since 1900, New York: St. Martin's Press, p. 131, ISBN 9780333618394. Also available online.

- ↑ Whiteman, Phyllis (1953), "Making the marriage bed", in Whiteman, Phyllis, Speaking as a woman, London: Chapman & Hall, p. 67, OCLC 712429455.

- ↑ Bruley, Sue (1999), "From austerity to prosperity and the pill: the Post-War years, 1945–c.1968", in Bruley, Sue, Women in Britain since 1900, New York: St. Martin's Press, p. 118, ISBN 9780333618394. Also available online.

- ↑ Pugh, Martin (1992), "The nadir of feminism and the climax of domesticity 1945-59", in Pugh, Martin, Women and the women's movement in Britain, 1914-1959, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan, p. 284, ISBN 9780333494400.

- ↑ Caine, Barbara (1997), "The postwar world", in Caine, Barbara, English feminism, 1780-1980, Oxford, England New York: Oxford University Press, p. 223, ISBN 9786610767090.

- ↑ Myrdal, Alva; Klein, Viola. Women's two roles: home and work. London: Routledge & Kegan. OCLC 896729837.

- Cited in Banks, Olive (1981). Faces of feminism: a study of feminism as a social movement. Oxford, England: Martin Robertson. p. 176. ISBN 9780855202606.

- ↑ Finch, Janet; Summerfield, Penny (1991), "Social reconstruction and the emergence of companionate marriage, 1945–59", in Clark, David, Marriage, domestic life, and social change: writings for Jacqueline Burgoyne, 1944-88, London New York, New York: Routledge, p. 11, ISBN 9780415032469.

- ↑ Ed Miliband, Leader of the Opposition (10 April 2013). "Tributes to Baroness Thatcher". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 1616–1617.

- ↑ Campbell, John (2000). Margaret Thatcher (vol. 2). London: Jonathan Cape. pp. 473–474. ISBN 9780224061568.

- ↑ Bassnett, Susan (2013), "Britain", in Bassnett, Susan, ed. (2013). Feminist experiences: the women's movement in four. London: Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 9780415636766.

- ↑ "Harman snatches an empty victory". The Sunday Times. 22 February 2009. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Harriet Harman will fill in for Brown at Prime Minister's Questions next week". London Evening Standard. 29 March 2008.

- ↑ Tavernor, Rachel (8 March 2013). "Sisterhood and after: first oral history archive of the UK Women’s Liberation Movement". REFRAME. School of Media, Film and Music, University of Sussex. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Whitfield, Bob (2001), "What was the status of women in Victorian society?", in Whitfield, Bob, ed. (2001). The extension of the franchise, 1832-1931. Oxford: Heinemann Educational. p. 122. ISBN 9780435327170.

- ↑ Kingsley Kent, Susan (2016), "Introduction", in Kingsley Kent, Susan, Sex and suffrage in britain 1860-1914, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, p. 7, ISBN 9780691635279.

- ↑ Lyndon Shanley, Mary (Autumn 1986). "Suffrage, protective labor legislation, and Married Women's Property Laws in England". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. Chicago Journals. 12 (1): 62–77. JSTOR 3174357. doi:10.1086/494297.

- ↑ Nym Mayhall, Laura E. (July 2000). "Defining militancy: radical protest, the constitutional idiom, and women's suffrage in Britain, 1908–1909". Journal of British Studies. Cambridge Journals. 39 (3): 350. JSTOR 175976. doi:10.1086/386223.

- ↑ Hume, Leslie (2016). The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies, 1897-1914. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9781138666726. Originally a Stanford University PhD thesis, (1979).

- ↑ Rowland, Peter (1978), "Conciliator-in-Chief, 1910-1914", in Rowland, Peter, ed. (1978). David Lloyd George:a biography. New York: Macmillan. p. 228. OCLC 609325280.

- ↑ Fawcett, Millicent (2011), "Appendix A: List of Acts of Parliament specially affecting the welfare, status, or liberties of women passed in the United Kingdom between 1902 and 1919", in Fawcett, Millicent, ed. (2011). The women's victory and after: personal reminiscences, 1911-1918. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 9781108026604.