Feline infectious peritonitis

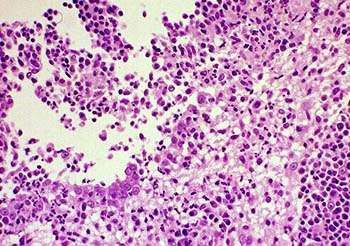

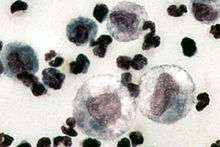

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a fatal, incurable disease that affects cats. It is caused by feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), which is a mutation of feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) – (Feline coronavirus FCoV). Experts do not agree on the specifics of genetic changes that produce the FIPV. The mutated virus has the ability to invade and grow in certain white blood cells, namely macrophages. The immune system's response causes an intense inflammatory reaction in the containing tissues. This disease is generally fatal.[1] However, its incidence rate is roughly 1 in 5,000 for households with one or two cats. A nasally administered vaccine for FIP is available but controversial, and it is not proven to be highly effective.[2] An experimental polyprenyl immunostimulant is being manufactured by Sass and Sass and tested by Dr. Al Legendre, who described survival over 1 year in three cats diagnosed with FIP and treated with the medicine.[3] In one case study, a female cat diagnosed with dry FIP has survived 26 months from the date of definitive diagnosis.

Transmission and infection

FECV is very common, especially in places where large groups of cats are kept together (animal shelters, catteries, etc.). Cats become infected by inhaling or ingesting the virus. The most commonly cited transmission source is feces, although contaminated surfaces such as food dishes and clothing can transmit the virus as well.

Despite the prevalence of FECV, most infected cats do not develop FIP. Often, exposure to FECV produces no clinical signs, but may cause a mild diarrhea. Therefore, a cat without clinical signs may still be an FECV carrier and may pass the virus to another cat. In any cat infected with FECV there is a chance that the virus may mutate into the FIP-causing form. This chance is increased for cats that are immune compromised, including very young and very old cats. There is also thought to be a genetic component to susceptibility to viral mutation.

Signs

There are two main forms of FIP: effusive (wet) and non-effusive (dry). While both types are fatal, the effusive form is more common (60-70% of all cases are wet) and progresses more rapidly than the non-effusive form.

Effusive (wet)

The hallmark clinical sign of effusive FIP is the accumulation of fluid within the abdomen or chest, which can cause breathing difficulties. Other symptoms include lack of appetite, fever, weight loss, jaundice, and diarrhea.

Non-effusive (dry)

Dry FIP will also present with lack of appetite, fever, jaundice, diarrhea, and weight loss, but there will not be an accumulation of fluid. Typically a cat with dry FIP will show ocular or neurological signs. For example, the cat may develop difficulty in standing up or walking, becoming functionally paralyzed over time. Loss of vision is another possible outcome of the disease.

Diagnosis

The signs associated with FIP are often non-specific, which can cause diagnosis to be very difficult. There is as yet no definitive diagnostic test for FIP. Diagnosis may include a combination strong clinical suspicion, physical examination findings, presence of abdominal fluid with characteristic chemistry changes and examination of affected tissues for the FIP virus (this is usually performed post-mortem, but can be performed via tissue biopsy). Histopathological examination of tissue samples is usually the cheapest available diagnostic test, but its sensitivity and specificity for FIP is questionable. A polymerase chain reaction test is also available for use with fluid or certain tissue samples; however, its efficacy is currently being reviewed.

More commonly, a presumptive diagnosis is made based on clinical signs and evaluation of abdominal or chest fluid, if available. Fluid caused by FIP tends to be yellow in color and have elevated protein levels. Blood tests can also be performed to bolster a presumptive diagnosis by looking for coronavirus antibodies and elevated protein. Coronavirus titres are NOT considered diagnostic in and of themselves due to the ubiquity of FeCoV, but may be used in conjunction with clinical symptoms to make an FIP diagnosis. It is important to note that cats with higher titres of FCoV are no more likely to develop FIP than those with lower titres.

In the presence of abdominal or chest fluid, a simple test called Rivalta test can be used to differentiate fluid resulting from FIP from fluids resulting from some other disease with very good accuracy.[4]

Treatment

Accepted wisdom is that there is no cure for FIP; treatment is symptomatic and palliative only, i.e. typically the owner is advised to make the cat as comfortable as possible. Prednisolone or other immunosuppressive drugs prescribed by a veterinarian may help to prolong the cat's life for a few weeks or months, but may be contraindicated in certain cases due to concomitant infection(s), although this risk can be mitigated somewhat by also treating with antibiotics. Newer approaches using immune modulators are being developed by several companies. In the paper by Legendre and Bartges (2009) cited above, three cats who received polyprenyl immunostimulant survived for over a year, and one of those cats whose treatment started in 2006 was still alive 8 years later as published by Cat Fancy.[5]

Effusive FIP usually progresses too rapidly for any meaningful therapy to be attempted.

Quarantine is often advised but may not be necessary in the light of new findings about the disease cycle. Feline Enteric Coronavirus is shed in the feces and can be passed on to other cats; however, it must undergo a mutation in order to lead to FIP.[6] Mutation may occur due to a number of factors (such as genetic susceptibility, viral strain, or impaired immunity due to stress or extremes of age) or it may never occur at all. This multifactorial nature is what accounts, in part, for the disparity between viral prevalence and disease incidence. This form is only found in macrophages and is therefore not shed and not contagious.

As FIP signs can be easily overlooked, it is highly advised to have the cat examined by a veterinarian at any signs of abdominal distention, changes in the eyes, chronic diarrhea, unusual lethargy or respiratory infection. While treatment will only be symptomatic, it may prolong the life of the cat as well as soften the blow to the owner. FIP patients can benefit from cytotoxic drugs such as methotrexate and cytoxan, and from corticosteroids such as methylprednisone or prednisolone; although it is not a cure, it often improves appetite and weight and can make the cat less lethargic. In some cases, cytotoxic drugs can induce a brief remission, and even corticosteroids alone can give the cat 3-5 more months of good-quality life. In spite of these treatments, however, prognosis remains extremely poor.

See also

References

- ↑ "Feline infectious peritonitis". Cornell University. 2012-08-21. Retrieved 2013-12-30.

- ↑ "Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP)". Vetinfo.com. Retrieved 2013-12-30.

- ↑ Legendre, Alfred M.; Bartges, Joseph W. (2009). "Effect of Polyprenyl Immunostimulant on the survival times of three cats with the dry form of feline infectious peritonitis". Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery. 11 (8): 624–6. PMID 19482534. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2008.12.002.

- ↑ Pedersen, Niels C. "An update on feline infectious peritonitis: Diagnostics and therapeutics". The Veterinary Journal. 201 (2): 133–141. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.04.016.

- ↑ "Hope for Nearly Fatal Cat Disease". Cat Channell. Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- ↑ http://www.askthecatdoctor.com/feline-fip.html

External links

- Feline Infectious Peritonitis and Coronavirus Website

- Feline Infectious Peritonitis from vetinfo.com

- Research on Feline Infectious Peritonitis from University of Tennessee, College of Veterinary Medicine

- FIP: A 2012 Update

- FIP Informational Brochure from the Cornell Feline Health Center

- UC Davis Center for Companion Animal Health

- Animal Health Channel

- Feline Advisory Bureau

- FIP (Felipedia.org)