Federal architecture

Federal-style architecture is the name for the classicizing architecture built in the newly founded United States between c. 1780 and 1830, and particularly from 1785 to 1815. This style shares its name with its era, the Federal Period. The name Federal style is also used in association with furniture design in the United States of the same time period. The style broadly corresponds to the classicism of Biedermeier style in the German-speaking lands, Regency architecture in Britain and to the French Empire style.

.jpg)

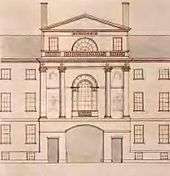

In the early American republic, the founding generation consciously chose to associate the nation with the ancient democracies of Greece and the republican values of Rome. Grecian aspirations informed the Greek Revival, lasting into the 1850s. Using Roman architectural vocabulary,[2] the Federal style applied to the balanced and symmetrical version of Georgian architecture that had been practiced in the American colonies' new motifs of neoclassical architecture as it was epitomized in Britain by Robert Adam, who published his designs in 1792.

Characteristics

American Federal architecture typically uses plain surfaces with attenuated detail, usually isolated in panels, tablets, and friezes. It also had a flatter, smoother façade and rarely used pilasters. It was most influenced by the interpretation of ancient Roman architecture, fashionable after the unearthing of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The bald eagle was a common symbol used in this style, with the ellipse a frequent architectural motif.

The classicizing manner of constructions and town planning undertaken by the federal government was expressed in federal projects of lighthouses and harbor buildings; hospitals; in the rationalizing, urbanistic layout of L'Enfant's city of Washington; and in New York the Commissioners' Plan of 1811.[3]

In two generations during which a gentleman's education included the ability to draw up an idiomatic classical elevation[4] for craftsmen who were themselves trained in the classical vocabulary, and where masons and house carpenters on their own produced a refined vernacular architecture, this American neoclassical high style was the idiom of America's first professional architects, in the generation of c. 1800, men such as Charles Bulfinch, architect of the Massachusetts State House, Boston, and Minard Lafever.

The two brothers, Robert Adam and James Adam, were Scottish architects who never visited America, but through their books were leading influences.[5]

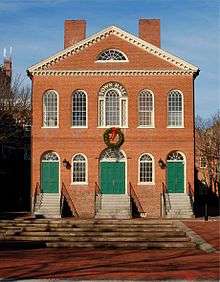

Legacy of Federal architecture in Salem, Massachusetts

In Salem, Massachusetts, there are numerous examples of American colonial architecture and Federal architecture in two historic districts: Chestnut Street District, which is part of the Samuel McIntire Historic District containing 407 buildings, and the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, consisting of 12 historic structures and about 9 acres (4 ha) of land along the waterfront.

Architects of the Federal period

- Asher Benjamin

- Charles Bulfinch

- John Holden Greene

- James Hoban

- Thomas Jefferson

- Minard Lafever

- Benjamin Latrobe

- Pierre L'Enfant

- Samuel Lewis

- John McComb, Jr.

- Samuel McIntire

- Robert Mills

- Alexander Parris

- William Strickland

- Martin E. Thompson

- William Thornton

- Ithiel Town

- Ammi B. Young

Modern reassessment of the American architecture of the Federal period began with Fiske Kimball, Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and the Early Republic, 1922.[6]

See also

- Adam style

- Boscobel (Garrison, New York)

- Federal furniture

- Hamilton Grange National Memorial

- Lyre arm

- Morris–Jumel Mansion

Footnotes

- ↑ Historical marker on Elfreth's Alley

- ↑ The design vocabulary of Federal architecture is accessibly illustrated and contrasted with Greek Revival in Rachel Carley, The Visual Dictionary of American Domestic Architecture 1994, ch. 5 "Neoclassical Styles", p. 90ff.

- ↑ For the federal government's role in Federal architectural style and its symbolism, see Lois Craig, ed. The Federal Presence: Architecture, Politics and Symbols in United States Government Building (Federal Architecture Project, Cambridge: MIT Press) 1978, chs. 1–3, with brief text and extended captions to multiple illustrations.

- ↑ Not, of course, designs as ambitious as those of Thomas Jefferson, an amateur who, in other circumstances, could have made a profession as architect.

- ↑ Creating Your Architectural Style. Pelican Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4556-0309-1.

- ↑ It "established a generation ago a scholarly basis for subsequent study of early American architecture", observes Hugh Morrison, in the Acknowledgments prefacing Early American Architecture From the First Colonial Settlements to the National Period (1951, repr. 1987), p. xiii.

Further reading

- Craig, Lois A., The Federal Presence: Architecture, Politics and National Design. The MIT Press: 1984. ISBN 0-262-53059-7.

External links

- Definition of Federal-style architecture

- Introduction to Federal-style architecture

- Federal Style, 1780-1820 - Coleman-Hollister House

- Federal Style Patterns 1780-1820 Bibliography for federal style research, photographs of federal houses, federal style pattern book.