Fantastic (magazine)

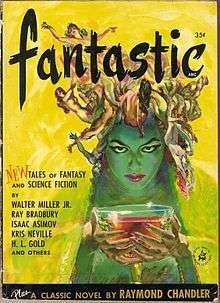

Cover of the October 1961 issue, by Alex Schomburg | |

| Editor | Howard Browne |

|---|---|

| Categories | Fantasy fiction, science fiction |

| Format | Digest size |

| Publisher | Ziff Davis |

| Year founded | 1952 |

| Final issue | 1980 |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Fantastic was an American digest size fantasy and science fiction magazine, published from 1952 to 1980. It was founded by Ziff Davis as a fantasy companion to Amazing Stories. Early sales were good, and Ziff Davis quickly decided to switch Amazing from pulp format to digest, and to cease publication of their other science fiction pulp, Fantastic Adventures. Within a few years sales fell, and Howard Browne, the editor, was forced to switch the focus to science fiction rather than fantasy. Browne lost interest in the magazine as a result and the magazine generally ran poor quality fiction in the mid-1950s, under Browne and his successor, Paul W. Fairman.

At the end of the 1950s Cele Goldsmith took over as editor of both Fantastic and Amazing, and quickly invigorated the magazines, bringing in many new writers and making them, in the words of one science fiction historian, the "best-looking and brightest" magazines in the field.[1] She helped to nurture the early careers of writers such as Roger Zelazny and Ursula K. Le Guin, but was unable to increase circulation, and in 1965 the magazines were sold to Sol Cohen, who hired Joseph Wrzos as editor and switched to a reprint-only policy. This was financially successful, but brought Cohen into conflict with the newly formed Science Fiction Writers of America. After a turbulent period at the end of the 1960s, Ted White became editor and the reprints were phased out.

White worked hard to make the magazine successful, introducing artwork from artists who had made their names in comics, and working with new authors such as Gordon Eklund. His budget for fiction was low, but he was occasionally able to find good stories from well-known writers which had been rejected by the other markets. Circulation continued to decline and in 1978 Cohen sold out his half of the business to his partner, Arthur Bernhard. White resigned shortly afterwards, and was replaced by Elinor Mavor, but within two years Bernhard decided to close down Fantastic, merging it with Amazing, which had always had slightly higher circulation.

Publishing history

In 1938, Ziff-Davis, a Chicago-based publisher looking to expand into the pulp magazine market, acquired Amazing Stories.[2] The number of science fiction magazines grew quickly; several new titles appeared over the next few years, including Fantastic Adventures, which was launched by Ziff-Davis in 1939 as a companion to Amazing.[3] Under the editorship of Raymond Palmer the magazines were reasonably successful but published poor quality work, and when Howard Browne took over as editor of Amazing in January 1950 he decided to try to move the magazine upmarket.[4][5] Ziff-Davis agreed to back the new magazine, and Browne put together a sample copy, but when the Korean War broke out Ziff-Davis cut their budgets and the project was abandoned.[6] Browne did not give up, and in 1952 received the go-ahead to try a new magazine instead, focused on high-quality fantasy,[7] a genre which had recently become more popular.[8] The first issue of Fantastic, dated Summer 1952, appeared on March 21 of that year.[7]

Early years

| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1952 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | |||||||||

| 1953 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | 2/5 | 2/6 | ||||||

| 1954 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/4 | 3/5 | 3/6 | ||||||

| 1955 | 4/1 | 4/2 | 4/3 | 4/4 | 4/5 | 4/6 | ||||||

| 1956 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 5/4 | 5/5 | 5/6 | ||||||

| 1957 | 6/1 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 6/4 | 6/5 | 6/6 | 6/7 | 6/8 | 6/9 | 6/10 | 6/11 | |

| 1958 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 7/4 | 7/5 | 7/6 | 7/7 | 7/8 | 7/9 | 7/10 | 7/11 | 7/12 |

| 1959 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | 8/4 | 8/5 | 8/6 | 8/7 | 8/8 | 8/9 | 8/10 | 8/11 | 8/12 |

| 1960 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 9/4 | 9/5 | 9/6 | 9/7 | 9/8 | 9/9 | 9/10 | 9/11 | 9/12 |

| Issues of Fantastic through 1960, identifying volume and issue numbers, and indicating editors: in sequence, Howard Browne, Paul Fairman, and Cele Goldsmith. Underlining indicates that an issue was titled as a quarterly (e.g. "Fall 1952") rather than as a monthly. | ||||||||||||

Sales were very good, and Ziff-Davis was sufficiently impressed to move the magazine from a quarterly to a bimonthly schedule after only two issues, and to switch Amazing from pulp format to digest-size to match Fantastic. Shortly afterwards the decision was taken to eliminate Fantastic Adventures: the March 1953 issue was the last, and the May–June 1953 issue of Fantastic added a mention of Fantastic Adventures to the masthead, though this disappeared with the following issue.[7] Payment started at two cents per word for all rights, but could go up to ten cents at the editor's discretion; this put Fantastic in the second echelon of magazines, behind markets such as Astounding and Galaxy.[9][10] The experiment with quality fiction did not last; circulation dropped, which led to budget cuts, and in turn the quality of the fiction fell. Browne had wanted to separate Fantastic from Amazing's pulp roots, but now found he had to print more science fiction (sf) and less fantasy in order to attract Amazing's readers to its sister magazine.[7] Fantastic's poor results were probably a consequence of the overloaded sf magazine market; far more magazines appeared in the early 1950s than the market was able to support. Ziff-Davis sales staff were able to help sell Fantastic and Amazing along with the technical magazines that it published, and the availability of a national sales network, even though it was not focused solely on Fantastic, undoubtedly helped the magazine to survive.[11]

In May 1956 Browne left Ziff-Davis to become a screenwriter. Paul W. Fairman took over as editor of both Fantastic and Amazing. In 1957 Bernard Davis left Ziff-Davis; it had been Davis who had suggested the acquisition of Amazing in 1939, and he had stayed involved with the sf magazines throughout the time he spent there. With his departure Amazing and Fantastic stagnated; they remained monthly but drew no attention from Ziff-Davis's management.[12]

Mid-1950s to late 1960s

In November 1955, Ziff-Davis hired an assistant, Cele Goldsmith, who began by helping with two new magazines under development, Dream World and Pen Pals. She also read the slush piles for all the magazines, and was quickly given more responsibility. In 1957 she was made managing editor of both Amazing and Fantastic, doing the administrative chores and reading unsolicited manuscripts; and at the end of 1958 she became editor, replacing Fairman, who left to edit Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine.[1][12] Goldsmith (who became Cele Lalli when she married in 1964) stayed as editor for six and a half years.[1]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | 10/1 | 10/2 | 10/3 | 10/4 | 10/5 | 10/6 | 10/7 | 10/8 | 10/9 | 10/10 | 10/11 | 10/12 |

| 1962 | 11/1 | 11/2 | 11/3 | 11/4 | 11/5 | 11/6 | 11/7 | 11/8 | 11/9 | 11/10 | 11/11 | 11/12 |

| 1963 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | 12/4 | 12/5 | 12/6 | 12/7 | 12/8 | 12/9 | 12/10 | 12/11 | 12/12 |

| 1964 | 13/1 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 13/4 | 13/5 | 13/6 | 13/7 | 13/8 | 13/9 | 13/10 | 13/11 | 13/12 |

| 1965 | 14/1 | 14/2 | 14/3 | 14/4 | 14/5 | 14/6 | 15/1 | 15/2 | ||||

| 1966 | 15/3 | 15/4 | 15/5 | 15/6 | 16/1 | 16/2 | ||||||

| 1967 | 16/3 | 16/4 | 16/5 | 16/6 | 17/1 | 17/2 | ||||||

| 1968 | 17/3 | 17/4 | 17/5 | 17/6 | 18/1 | 18/2 | ||||||

| 1969 | 18/3 | 18/4 | 18/5 | 18/6 | 19/1 | 19/2 | ||||||

| 1970 | 19/3 | 19/4 | 19/5 | 19/6 | 20/1 | 20/2 | ||||||

| Issues of Fantastic from 1961 to 1970, identifying volume and issue numbers, and indicating editors: in sequence, Cele Goldsmith (Lalli), Joseph Ross, Harry Harrison, Barry Malzberg, and Ted White | ||||||||||||

Circulation dropped for both Amazing and Fantastic; in 1964 Fantastic had a paid circulation of only 27,000.[13] In 1965 Sol Cohen, who at that time was Galaxy's publisher, set up his own publishing company, Ultimate Publishing, and bought both Amazing and Fantastic from Ziff-Davis.[1][notes 1] Cohen had decided to make the magazines as profitable as possible by filling them only with reprints. This was possible because Ziff-Davis had acquired second serial rights for all stories they had published, and since Cohen had bought the backfile of stories he was able to reprint them using these rights.[1][15] Using reprints in this way saved Cohen about $8,000 a year between the two magazines.[15] Lalli decided that she did not want to work for Cohen, and stayed with Ziff-Davis. Her last issue was June 1965. Cohen replaced Lalli with Joseph Wrzos, who used the name "Joseph Ross" on the magazines.[1][13] Cohen had met Wrzos at the Galaxy offices not long before; Wrzos was teaching English full-time, but had worked for Gnome Press as an assistant editor in 1953–1954.[13]

Cohen also launched a series of reprint magazines, drawing from the backfile of both Amazing and Fantastic, again using the second serial rights he had acquired from Ziff-Davis. The first reprint magazine was Great Science Fiction; the first issue, titled Great Science Fiction from Amazing, appeared in August 1965. By early 1967 this had been joined by The Most Thrilling Science Fiction Ever Told and Science Fiction Classics. These increased the workload on Wrzos, though Cohen made the selection of stories, and Wrzos found himself able to work on Fantastic and Amazing only part-time. Cohen hired Herb Lehrman to help with the other magazines.[13]

Although Cohen felt that his deal with Ziff-Davis gave him the reprint rights he needed, the newly formed Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) received complaints about Cohen's refusal to pay anything for the reprints. He was also reportedly not responding to requests for reassignment of copyright. SFWA organized a boycott of Cohen's magazines; after a year Cohen agreed to pay a flat fee for the reprints, and in August 1967 he agreed to a graduated scale of payments, and the boycott was withdrawn.[13]

Harry Harrison had been involved in the negotiations between SFWA and Cohen, and when the agreement was reached in 1967 Cohen asked Harrison if he would take over as editor of both magazines. Harrison was available because SF Impulse, which he had been editing, had ceased publication in early 1967. Cohen agreed to phase out the reprints by the end of the year, and Harrison took the job. Cohen added Harrison's name to the masthead of two issues of Great Science Fiction, although Harrison had had nothing to do with that magazine, but the reprints in Fantastic and Amazing continued and Harrison decided to quit in February 1968. He recommended Barry Malzberg as his replacement. Cohen had worked with Malzberg at the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, and felt Malzberg would be more cooperative than Harrison. Malzberg, however, turned out to be just as unwilling as Harrison to work with Cohen if the reprints continued, and soon regretted taking the job. In October 1968 Cohen refused to pay for a cover that Malzberg had commissioned; Malzberg insisted, threatening to resign if Cohen did not agree. Cohen contacted Robert Silverberg, then the president of SFWA, and told him (falsely) that Malzberg had actually resigned. Silverberg recommended Ted White as a replacement. Cohen secured White's agreement and then fired Malzberg; White took over in October 1968, but because there was a backlog of stories Malzberg had acquired, the first issue on which he was credited as editor was the June 1969 issue.[13][15]

1970s to Present

Like his immediate predecessors, White took the job on condition that the reprints would be phased out. It was some time before this was achieved: there was at least one reprinted story in every issue until the end of 1971. The February 1972 issue contained some artwork reprinted from 1939, and after that the reprints ceased.[15][16]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 20/3 | 20/4 | 20/5 | 20/6 | 21/1 | 21/2 | ||||||

| 1972 | 21/3 | 21/4 | 21/5 | 21/6 | 22/1 | 22/2 | ||||||

| 1973 | 22/3 | 22/4 | 22/5 | 22/6 | 23/1 | |||||||

| 1974 | 23/2 | 23/3 | 23/4 | 23/56 | 23/6 | 24/1 | ||||||

| 1975 | 24/2 | 24/3 | 24/4 | 24/5 | 24/6 | 25/1 | ||||||

| 1976 | 25/2 | 25/3 | 25/4 | 25/5 | ||||||||

| 1977 | 26/1 | 26/2 | 26/3 | 6/4 | ||||||||

| 1978 | 27/1 | 27/2 | 27/3 | |||||||||

| 1979 | 27/4 | 27/5 | 27/6 | 27/7 | ||||||||

| 1980 | 27/8 | 27/9 | 27/10 | 27/11 | ||||||||

| Issues of Fantastic from 1971 to 1980, identifying volume and issue numbers, and indicating editors: Ted White through most of the decade, and then Elinor Mavor. Note that the apparent error in volume numbering at the end of 1977 is in fact correct. | ||||||||||||

Fantastic's circulation was about 37,000 when White took over; only about 4 percent of this was subscription sales. Cohen's wife filled the subscriptions from their garage, and according to White, Cohen regarded this as a burden, and never tried to increase the subscription base.[15] Despite White's efforts, Fantastic's circulation fell, from almost 37,000 when he took over as editor to less than 24,000 in the summer of 1975. Cohen was rumored to be interested in selling both Fantastic and Amazing; among other possibilities, both Roger Elwood, at that time an active science fiction anthology editor, and Edward Ferman, the editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, approached Cohen with a view to acquiring the titles. Nothing came of it, however, and White was not aware of the possible sales. He was working at a low salary, with unpaid help from friends to read unsolicited submissions—at one point he introduced a 25-cent reading fee for manuscripts from unpublished writers; the fee would be refunded if White bought the story. White sometimes found himself at odds with Cohen's business partner, Arthur Bernhard, due to their different political views.[17] White's unhappiness with his working conditions culminated in his resignation after Cohen refused his proposal to publish Fantastic as a slick magazine, with larger pages and higher quality paper.[17] White commented in an article in Science Fiction Review that he had brought to the magazines "a lot of energy and enthusiasm and a great many ideas for their improvement ...Well, I have put into effect nearly every idea which I was allowed to follow through on ... and have spent most of my energy and enthusiasm."[18] Cohen was able to persuade him to stay for another year; in the event White stayed for another three.[17]

White was unable to completely halt the slide in circulation, though it rose a little in 1977. That year Cohen lost $15,000 dollars on the magazines, and decided to sell.[17] He spent some time looking for a new publisher—editor Roy Torgeson was one of those interested—but on September 15, 1978, he sold his half of the business to Arthur Bernhard, his partner.[19] White renewed his suggestions for improving the format of the magazine: he wanted to make Fantastic the same size as Time, and believed he could avoid the mistakes that had been made by other sf magazines that had tried that approach. White also proposed an increase in the budget and asked for a raise. Bernhard not only turned down White's ideas, but also stopped paying him: White responded by resigning. His last official day as editor was November 9; the last issue of Fantastic under his control was the January 1979 issue. He returned all submissions to their authors, saying that he had been told to do so by Bernhard; Bernhard denied this.[19]

Bernhard brought in Elinor Mavor to edit both Amazing and Fantastic. Mavor had previously edited Bill of Fare, a restaurant trade journal, and was a long-time science fiction reader, but she had little knowledge of the history of the magazines. She was unaware, for example, that she was not the first woman to edit them, and so adopted a male pseudonym—"Omar Gohagen"—for a while.[19] She suggested a campaign to increase circulation, and went so far as to gather information about costs while on a trip to New York in 1979. Bernhard decided instead to merge the two magazines. Circulation was continuing to drop; the figures for the last two years are not available, but sf historian Mike Ashley estimates that Fantastic paid circulation may have been as low as 13,000.[notes 2] Bernhard felt that since Fantastic had never been profitable, whereas Amazing had made money, it was best to keep Amazing.[19] Until the March 1985 issue, Amazing included a mention of Fantastic on the spine and on the contents page.[16] In 1999, the fiction magazine formerly known as Pirate Writings revived the Fantastic title and Cele Goldsmith-era logotype for several issues, ultimately unsuccessfully, though this was not intended as a continuation of the original magazine.[20]

In August 2014, Warren Lapine, former editor of Absolute Magnitude, Realms of Fantasy, and Weird Tales, revived the Fantastic logotype of Fantastic Stories of the Imagination as a free webzine.[21]

Contents and reception

Browne and Fairman

The first issue of Fantastic was impressive, with a cover that sf historian Mike Ashley has described as "one of the most captivating of all first issues"; the painting, by Barye Phillips and Leo Summers, illustrated Kris Neville's "The Opal Necklace". The fiction included some stories by well known names; in particular, Raymond Chandler's "Professor Bingo's Snuff" would have caught readers' eyes—the story had appeared the year before in Park East magazine, but would have been new to most readers. It was a short mystery in which the fantasy element was invisibility, achieved by magical snuff. Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury also contributed stories, and the issue led with "Six and Ten Are Johnny", by Walter M. Miller. The rear cover reprinted Pierre Roy's painting "Danger on the Stairs", which depicted a snake on a staircase; it was an odd choice, but subsequent back covers were more natural fits for a fantasy magazine. The quality of the fiction continued to be high for the first year; sf historian Mike Ashley comments that almost every story in the first seven issues was of high quality,[7] and historian David Kyle regards it as an "outstandingly successful experiment".[22] Science fiction bibliographer Donald Tuck dissents, however, regarding the first few years as containing "little of note",[23] and James Blish wrote a contemporary review of the second issue which found it lacking: Blish dismissed three of the seven stories in the Fall 1952 issue as being essentially crime stories written for the sf market, and commented that of the remaining four, only two were "reasonably competent and craftsmanlike".[24]

Other well-known writers appeared in the early issues, including Shirley Jackson, B. Traven, Truman Capote and Evelyn Waugh.[8] Mickey Spillane had written a story called "The Woman With Green Skin", but had been unable to sell it; Browne offered to buy it on condition that he had permission to rewrite it as he wished. This was agreed and Browne scrapped Spillane's text completely, writing a new story called "The Veiled Woman" and publishing it as by Spillane in the November–December 1952 issue. The issue sold so well it was reprinted, with over 300,000 copies sold.[7]

The emphasis was on fantasy, and much of it was "slick" fantasy—the sort of genre fiction that the upmarket slick magazines, such as The Saturday Evening Post, were willing to buy.[8] Some science fiction appeared as well in the first couple of years, including Isaac Asimov's "Sally", which portrays a world in which cars have been given robotic brains and are intelligent.[7] In 1955 it was decided to move the focus from fantasy to sf: in Browne's words, "Stories of straight fantasy were largely eliminated and straight science-fiction substituted, cover subject matter became of a scientific nature, the words "science fiction" appeared under the title, interior artwork was tightened up to replace the loose, 'arty' kind of drawing we had been using." Sales rose 17% within two issues.[7][25] Browne was uninterested in science fiction, however, and the quality of the fiction soon dropped, with a small stable of writers producing much of Fantastic's fiction under house names over the next couple of years.[7] By the start of 1956 the fiction in Fantastic was, in the opinion of sf historian Mike Ashley, "[in] a trough of hack predictability",[26] but there was some inventiveness evident from newer writers such as Robert Silverberg, Harlan Ellison and Randall Garrett.[8]

Although Browne had been unable to make Fantastic successful by specializing in fantasy, he was still interested in the fantasy genre, and experimented in the December 1955 issue with the theme of wish fulfilment. He dropped the words "Science Fiction" from the cover, and published five stories, all of which dealt with male fantasies in one form or another. The cover showed a man walking through a wall to find a woman undressing; the art was by Ed Valigursky and illustrated Paul Fairman's "All Walls Were Mist". Reader reaction, according to Browne, was almost entirely favorable, and he continued to publish occasional stories on the wish-fulfilment theme. The experiment was repeated with the October 1956 issue, which again ran without "Science Fiction" on the cover, and contained stories on the theme of "Incredible Powers". Once again the cover illustrated a male fantasy: this time it showed a man materializing in a bath house where women were showering. Browne had left Ziff-Davis by the time this issue appeared, but Browne's plans for a magazine around these themes were well advanced, and Fairman, who by this time was editing both Fantastic and Amazing, was given Dream World to edit as well. It ran for three quarterly issues, starting in February 1957, but proved too narrow a market to succeed.[27]

Fairman devoted the July 1958 issue of Fantastic to the Shaver Mystery—a lurid set of beliefs propounded by Richard Shaver in the late 1940s that told of "detrimental robots", or "deros", who were behind many of the disasters that befell humanity. Most of these stories had run in Amazing, though the editor at that time, Ray Palmer, had been forced to drop Shaver by Ziff-Davis when the stories began to attract ridicule in the press. Fantastic's readers were no kinder, complaining vigorously.[28][29]

Goldsmith

When Goldsmith took over as editor, there was some concern at Ziff-Davis that she might not be able to handle the job. A consultant, Norman Lobsenz, was brought in to help her; Lobsenz's title was "editorial director", but in fact Goldsmith made the story selections. Lobsenz provided blurbs and editorials, read the stories Goldsmith bought, and met with Goldsmith every week or so. Goldsmith was not a long-time sf reader, and knew little about the field; she simply looked for good quality fiction and bought what she liked. In Mike Ashley's words, "the result, between 1961 and 1964, was the two most exciting and original magazines in the field". New writers whose first story appeared in Fantastic during this period included Phyllis Gotlieb, Larry Eisenberg, Ursula K. Le Guin, Thomas M. Disch, and Piers Anthony.[1] The November 1959 issue was dedicated to Fritz Leiber; it included "Lean Times in Lankhmar", one of Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories. Goldsmith published another half-dozen stories in the series over the next six years, along with other similar (and sometimes imitative) fiction such as early work by Michael Moorcock, and John Jakes' early stories of Brak the Barbarian. This helped to invigorate the nascent sword and sorcery subgenre.[1][8][16] Goldsmith obtained an early story by Cordwainer Smith, "The Fife of Bodidharma", which ran in the June 1959 issue, but shortly thereafter Pohl at Galaxy reached an agreement to get first refusal on all Smith's work.[1]

During the early 1960s Goldsmith managed to make Fantastic and Amazing, in the words of Mike Ashley, "the best-looking and brightest" magazines around. This applied both to the covers, where Goldsmith used artists such as Alex Schomburg and Leo Summers, and the content.[1] Ashley also describes Fantastic as the "premier fantasy magazine" during Goldsmith's tenure—at that time the only other magazine focused specifically on fantasy fiction was the British Science Fantasy.[8]

Goldsmith's tastes were too diverse for Fantastic to be limited to genre fantasy, however, and her willingness to buy fiction she liked, regardless of genre expectations, allowed many new writers to flourish on the pages of both Amazing and Fantastic. Writers such as Ursula K. Le Guin, Roger Zelazny and Thomas M. Disch sold regularly to her at the start of their careers[8] Le Guin later commented that Goldsmith was "as enterprising and perceptive an editor as the science fiction magazines ever had".[30] Not all Goldsmith's choices were universally popular with the magazine's subscribers: she regularly published fiction by David R. Bunch, for example, to mixed reviews from the readership.[8]

Reprint era

Wrzos persuaded Cohen that both Amazing and Fantastic should carry a new story in every issue, rather than running nothing but reprints; Goldsmith had left a backlog of unpublished stories, and Wrzos was able to stretch these out for some time. One such story was Fritz Leiber's "Stardock", another Fafhrd and Gray Mouser story, which appeared in the September 1965 issue; it was subsequently nominated for a Hugo Award. The reprints were well received by the fans, because Wrzos was able to find good quality stories that were unavailable except in the original magazines, meaning that to many of Fantastic's readers they were fresh material. Wrzos also reprinted "The People of the Black Circle", a Robert E. Howard story from Weird Tales, in 1967, when Howard's Conan stories were becoming popular.[13]

In addition to the backlog of new stories from the Ziff-Davis era, Wrzos was able to acquire some new material. He was especially glad to acquire "For a Breath I Tarry", by Roger Zelazny; however, he had to wait for Cohen's approval for his acquisitions. Cohen, perhaps uncertain because of the story's originality, delayed until it appeared in the British magazine New Worlds before agreeing to publish it. Wrzos commented years later that he would "never forgive him [Cohen] his timidity at that time".[13] Wrzos bought Doris Piserchia's first story, "Rocket to Gehenna", and was the first editor to acquire a story by Dean Koontz. He had to work with Koontz to improve it, and the delay this caused, in addition to the slow publishing schedule for new material, meant that Koontz appeared in print with "Soft Come the Dragons", in the August 1967 Fantasy & Science Fiction, before "A Darkness in My Soul" appeared in the January 1968 Fantastic.[13]

After Wrzos's departure, Harrison and Malzberg had little opportunity to reshape the magazine as between them they only took responsibility for a handful of issues before Ted White took over. However, Harrison did print James Tiptree's first sale, "Fault", in the August 1968 issue; again the slow schedule meant that this was not Tiptree's first appearance in print. Harrison added a science column by Leon Stover, but was unable to change Cohen's position on the reprints, and so could not print much new fiction. When Malzberg took over from Harrison he published John Sladek, Thomas M. Disch, and James Sallis, all of whom were associated with New Wave science fiction, but his tenure was too short for him to have a significant impact on the magazine.[13]

White and Mavor

White was only able to offer his writers one cent per word, which was substantially lower than the leading magazines in the field—Analog Science Fiction and Fact paid five cents, and Galaxy and Fantasy & Science Fiction paid three. Most stories would only be submitted to White once the higher-paying markets had rejected them, but among the rejects White was sometimes able to find experimental material that he liked. For example, Piers Anthony had been unable to sell an early fantasy novel, Hasan; White saw a review of the manuscript and promptly acquired it for Fantastic, where it was serialized starting in the December 1969 issue.[15] White also took care to establish relationships with newer writers. White bought Gordon Eklund's first story, "Dear Aunt Annie", it appeared in the April 1970 issue and was nominated for a Nebula award. Eklund was unwilling to become a full-time writer, despite this success, because of the financial risks, so White agreed to buy anything Eklund wrote, on condition that Eklund himself believed it was a good story. The result was that much of Eklund's fiction appeared in Amazing and Fantastic over the next few years.[31] In addition to experimental work, White was able to obtain material by some of the leading sf writers of the day, including Brian Aldiss and John Brunner.[15] White also acquired some early work by writers who became better known in other fields: Roger Ebert sold two stories in the early 1970s to Fantastic; the first, "After the Last Mass", appeared in the February 1972 issue; and in 1975 White bought Ian McEwan's second story, "Solid Geometry". It was included in First Love, Last Rites, McEwan's first short story collection, which won the Somerset Maugham Award in 1976.[15]

White had been an active science fiction fan before he became professionally involved in the field, and although he estimated that only 1 in 30 readers were active sf fans, he tried to use this fan base to help by urging the readership to give him feedback and to help with distribution by checking local newsstands for the magazines. White wanted to introduce established artists from outside the sf field, such as Jeff Jones, Vaughn Bodé, and Steve Hickman; however, the company was saddled with cheap artwork acquired from European magazines to be used for the cover and he was instructed to make use of them.[15] He commissioned a comic strip from Vaughn Bodé, but was outbid by Judy-Lynn Benjamin at Galaxy; he subsequently told his readers that he'd signed up Bodé again for interior artwork, but this never materialized.[32][33][34] Instead a four-page comic strip by Jay Kinney appeared in December 1970; a second strip, by Art Spiegelman, was planned, but never published.[15] Eventually White was allowed to commission original cover art; he published early work by Mike Hinge, and Mike Kaluta made his first professional sale to Fantastic. He tried to hire Hinge as art director, but this fell through and White filled the role himself, sometimes using the pseudonym "J. Edwards".[15]

Because of poor distribution, Fantastic was never able to benefit from the increasing popularity of the fantasy genre, though White was able to publish several stories by well-known writers in the field, including a sword and sorcery novella by Dean R. Koontz, which appeared in the October 1970 issue, and an Elric story by Michael Moorcock in February 1972.[8][15] A revival of Robert E. Howard's character Conan, in stories by L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter, was successful at increasing sales; the first of these stories appeared in August 1972, and White reported that sales of that issue were higher than for any other issue of Amazing or Fantastic that year. Each Conan story, according to White, increased sales of that issue by 10,000 copies. White also published several of Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories, and added "Sword and Sorcery" to the cover in 1975.[15] In the same year a companion magazine, Sword & Sorcery Annual, was launched, but the first issue was the only one to appear.[8]

The quality of the magazine remained high even as the financial stress was mounting in the late 1970s. White acquired cover artwork by Stephen Fabian and Douglas Beekman, and stories by some of the new generation of sf writers, such as George R. R. Martin and Charles Sheffield.[15] White departed in November 1978, but the first issue of Fantastic under Elinor Mavor's editorial control was April 1979. Because White had returned unsold stories she had very little to work with and was forced to fill the magazine with reprints. This led to renewed conflict with the sf community, which she did her best to defuse. At a convention in 1979 she met Harlan Ellison, who complained about the reprint policy; she explained that it was temporary and was able to get him to agree to contribute stories, publishing two pieces by him in Amazing over the next three years. The January 1980 issue of Fantastic (Mavor's fourth issue) was the last to contain reprinted stories.[19] Once the reprints had been phased out, Mavor was able to find new writers to work with, including Brad Linaweaver and John E. Stith, both of whom sold their first stories to Fantastic.[19] The last year of Fantastic showed "a steady improvement in content", according to Mike Ashley, who cites in particular Daemon, a serialized graphic story, illustrated by Stephen Fabian. However, at the end of 1980 Fantastic's independent existence ceased, and it was merged with Amazing.[19]

Publication details

Editors

The list below gives the person who was acting as editor. In some cases, such as at the start of Cele Goldsmith's stint, the official editor was not the same person; details are given above.[35]

- Howard Browne (Summer 1952 – August 1956).

- Paul Fairman (October 1956 – November 1958).

- Cele Goldsmith (December 1958 – June 1965). Goldsmith used her married name, Cele G. Lalli, from July 1964.

- Joseph Ross (September 1965 – November 1967).

- Harry Harrison (January 1968 – October 1968).

- Barry N. Malzberg (December 1968 – April 1969).

- Ted White (June 1969 – January 1979)

- Elinor Mavor (April 1979 – October 1980)

Other bibliographic details

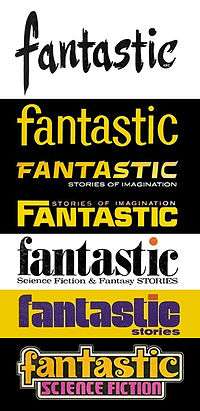

The title changed multiple times, and was frequently inconsistently given between the cover, spine, indicia, and masthead.[16][36]

| Start month | End month | Cover | Spine | Indicia | Masthead | Number of issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer-52 | Feb-55 | Fantastic | Fantastic | Fantastic | Fantastic | 16 |

| Apr–55 | Oct–55 | Fantastic Science-Fiction | 4 | |||

| Dec–55 | Dec–55 | Fantastic | 1 | |||

| Feb–56 | Aug–56 | Fantastic Science-Fiction | 4 | |||

| Oct–56 | Oct–56 | Fantastic | 1 | |||

| Dec–56 | Sep–57 | Fantastic Science-Fiction | 9 | |||

| Oct–57 | Feb–58 | Fantastic Science Fiction | 5 | |||

| Mar–58 | Aug–59 | Fantastic | 18 | |||

| Sep–59 | Dec–59 | Fantastic Science Fiction Stories | Fantastic Science Fiction Stories | Fantastic Science Fiction Stories | 4 | |

| Jan-60 | Sep-60 | Fantastic Science Fiction Stories | 9 | |||

| Oct-60 | Jun-65 | Fantastic Stories of Imagination | Fantastic Stories of Imagination | Fantastic | Fantastic Stories of Imagination | 57 |

| Sep-65 | Dec-69 | Fantastic Science Fiction – Fantasy | Fantastic Stories | Fantastic Science Fiction – Fantasy | 26 | |

| Feb-70 | Apr-71 | Fantastic Stories Science Fiction – Fantasy | 8 | |||

| Jun-71 | Apr-72 | Fantastic Stories Science Fiction & Fantasy | Fantastic Stories Science Fiction & Fantasy | 6 | ||

| Jun-72 | Jun-72 | Fantastic Stories Science Fiction & Fantasy | 1 | |||

| Aug-72 | Aug-72 | Fantastic Stories | 1 | |||

| Oct-72 | Feb-75 | Fantastic Stories Science Fiction & Fantasy | 14 | |||

| Apr-75 | Jun-77 | Fantastic Stories Sword & Sorcery and Fantasy | Fantastic Stories Swords & Sorcery and Fantasy | 11 | ||

| Sep-77 | Oct-78 | Fantastic Stories | Fantastic Stories | Fantastic Stories Sword & Sorcery and Fantasy | 5 | |

| Jan-79 | Jan-79 | Fantastic Stories Science Fiction & Fantasy | Fantastic Stories Science Fiction & Fantasy | Fantastic Stories Science Fiction & Fantasy | 1 | |

| Apr-79 | Oct-80 | Fantastic Science Fiction | Fantastic Stories | Fantastic Science Fiction | 7 |

The following table shows which issues appeared from which publisher.[16][35]

| Dates | Publisher |

|---|---|

| Summer 1952 – June 1965 | Ziff-Davis, New York |

| September 1965 – January 1979 | Ultimate Publishing, Flushing, New York |

| April 1979 – October 1980 | Ultimate Publishing, Purchase, New York |

A British edition published by Thorpe & Porter ran for eight bimonthly issues from December 1953 to February 1955; the issues were not dated on the cover. These correspond to the US issues from September/October 1953 to December 1954, and were numbered volume 1, numbers 1 through 8.[23][35]

Fantastic was digest-sized throughout its life. The page count began at 160 but dropped to 144 with the September/October 1953 issue, and then again to 128 pages with the very next issue, November/December 1953. The July 1960 issue had 144 pages, but apart from that one issue the page count stayed at 128 until September 1965, when it increased to 160. In January 1968 it went back down to 144 pages, and it dropped to 128 pages from February 1971 through the end of its run. The first issue was priced at 35 cents; thereafter the price went up as follows: 50 cents in May 1963, 60 cents in December 1969, 75 cents in July 1974, $1.00 in October 1975, $1.25 in April 1978, and finally $1.50 from April 1979 until the last issue.[35]

Derivative anthologies

Three anthologies of stories from Fantastic have been published. Note that Time Untamed contains stories that were published in Fantastic during its reprint years, but which did not necessarily first appear there.[8][35]

| Year | Editor | Title | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | Ivan Howard | Time Untamed | Belmont: New York |

| 1973 | Ted White | The Best From Fantastic | Manor Books: New York |

| 1987 | Martin H. Greenberg & Patrick Lucien Price | Fantastic Stories: Tales of the Weird and Wondrous | TSR: Lake Geneva, Wisconsin |

Notes

- ↑ Cohen was Galaxy's publisher, but not the owner; the owner was Robert Guinn, who is also often referred to as the publisher.[14]

- ↑ The circulation figures were published from 1962 through 1979, but not for 1980 as Fantastic did not exist in 1981 to publish the data. In addition the 1979 data is almost certainly incorrect as it is an exact duplicate of the 1978 data, so there is no available circulation data for 1979 either.[19]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ashley, Transformations, pp. 222–228.

- ↑ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 115.

- ↑ Mike Ashley, "Fantastic Adventures", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines, p. 232.

- ↑ Mike Ashley, "Fantastic Adventures", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines, pp. 237–238.

- ↑ Mike Ashley, "Amazing Stories", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines, p. 34.

- ↑ Ashley, Transformations, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ashley, Transformations, pp. 48–51.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Mike Ashley, "Fantastic", in Clute & Grant, Encyclopedia of Fantasy (1997), pp. 335–336.

- ↑ de Camp, Science-Fiction Handbook, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ de Camp, Science-Fiction Handbook, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ del Rey, The World of SF, pp. 194–195.

- 1 2 Ashley, Transformations, pp. 172–175.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ashley, Transformations, pp. 263–268.

- ↑ Pohl, The Way the Future Was, pp. 201–202.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Ashley, Gateways, pp. 69–86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 See the individual issues. For convenience, an online index is available at "Magazine:Fantastic – ISFDB". Al von Ruff. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Ashley, Gateways to Forever, pp. 84–86.

- ↑ Ted White, "Uffish Thots", Science Fiction Review #12 (February 1975), quoted in Ashley, Gateways to Forever, p. 85; ellipses in quote are as given by Ashley.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ashley, Gateways to Forever, pp. 347–353.

- ↑ "Pirate Writings". Gollancz/SFE Ltd. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ↑ "Fantastic Stories of the Imagination Returns". Wilder Publications. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ↑ Kyle, Pictorial History, p. 116.

- 1 2 "Fantastic", in Tuck, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Vol. 3, pp. 557–558.

- ↑ Atheling, The Issue at Hand, pp. 23–25.

- ↑ Howard Browne, "Low Man on the Asteroid", in Fantastic vol. 4, no 5 (October 1965), p. 4.

- ↑ Ashley, Transformations, p. 162.

- ↑ Ashley, Transformations, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Ashley, Transformations, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ Ashley, Transformations, pp. 179–183.

- ↑ Quoted in Malcolm Edwards, "Cele Goldsmith", in Clute & Nicholls, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (1993), p. 508.

- ↑ Ashley, Gateways, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Ashley, Gateways, p. 39.

- ↑ "According to You". Fantastic. 20 (2): 135. December 1970.

- ↑ "Editorial". Fantastic. 20 (2): 143. December 1970.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mike Ashley, "Fantastic", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines, pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Mike Ashley, "Fantastic", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Weird Fiction Magazines, p. 231.

References

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines:The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Ashley, Mike (2005). Transformations: The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-779-4.

- Ashley, Mike (2007). Gateways to Forever:The Story of the Science-Fiction Magazines from 1970 to 1980. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-003-4.

- Atheling, Jr., William (1967). The Issue at Hand. Chicago: Advent: Publishers, Inc.

- Clute, John; Grant, John (1997). The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc. ISBN 0-312-15897-1.

- Clute, John; Peter Nicholls (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- de Camp, L. Sprague (1953). Science-Fiction Handbook: The Writing of Imaginative Fiction. New York: Hermitage House.

- del Rey, Lester (1979). The World of Science Fiction: 1926–1976: The History of a Subculture. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25452-X.

- Kyle, David (1977). The Pictorial History of Science Fiction. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-38193-5.

- Pohl, Frederik (1979). The Way the Future Was. London: Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-02672-3.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1982). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3. Chicago: Advent. ISBN 0-911682-26-0.

- Tymn, Marshall B.; Mike Ashley (1985). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. West: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

External links

Media related to Fantastic (magazine) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fantastic (magazine) at Wikimedia Commons