Falun Mine

The Copper Mine in Falun, the Great Pit | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| Location |

Falun Municipality, Sweden |

| Coordinates | 60°36′17″N 15°37′51″E / 60.6047°N 15.6308°E |

| Includes |

Falun copper mine Gamla Herrgården Linnés bröllopsstuga Stora Kopparberg church Elsborg Kristine church Östanfors |

| Criteria |

Cultural: (ii), (iii), (v) |

| Reference | 1027 |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th Session) |

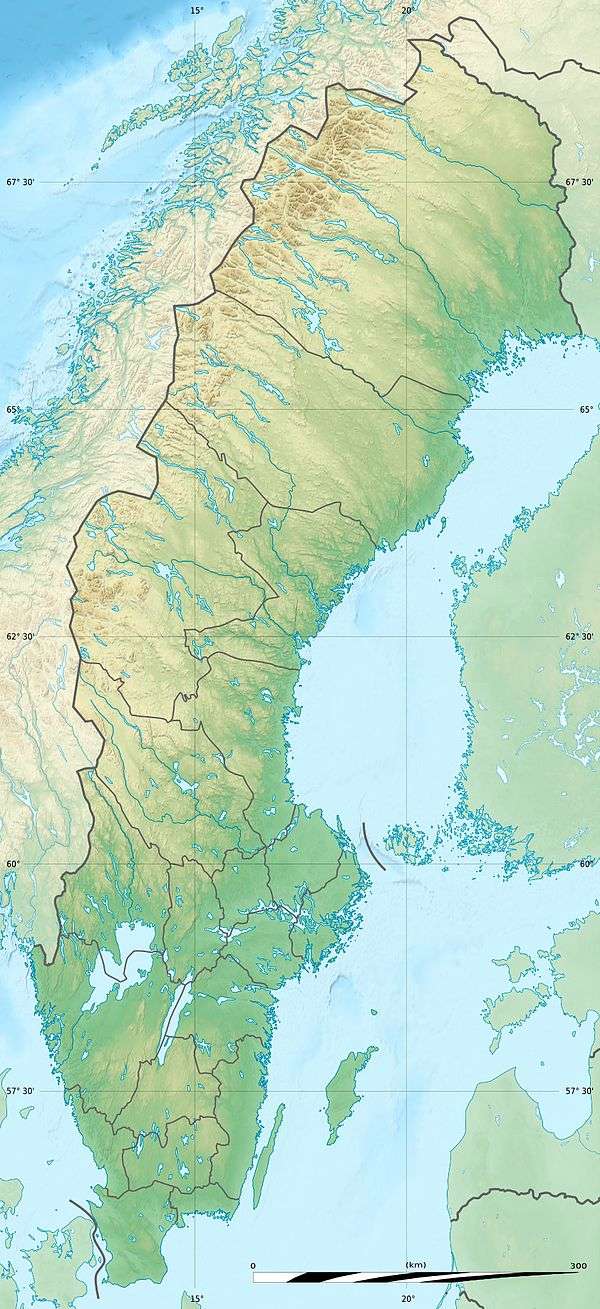

Location of Falun Mine | |

Falun Mine (Swedish: Falu Gruva) was a mine in Falun, Sweden, that operated for a millennium from the 10th century to 1992. It produced as much as two thirds of Europe's copper needs[2] and helped fund many of Sweden's wars in the 17th century. Technological developments at the mine had a profound influence on mining globally for two centuries.[3] The mine is now a museum and in 2001 was designated a UNESCO world heritage site.

History

There are no written accounts establishing exactly when mining operations at Falun Mine began. Archaeological and geological studies indicate, with considerable uncertainty, that mining operations started sometime around the year 1000. No significant activities had begun before 850, but the mine was definitely operating by 1080. Objects from the 10th century have been found containing copper from the mine. In the beginning, operations were of a small scale, with local farmers gathering ore, smelting it, and using the metal for household needs.[4]

Around the time of Magnus III, king of Sweden from 1275 to 1290, a more professional operation began to take place. Nobles and foreign merchants from Lübeck had taken over from farmers. The merchants transported and sold the copper in Europe but also influenced the operations and developed the methods and technology used for mining. The first written document about the mine is from 1288; it records that, in exchange for an estate, the Bishop of Västerås acquired a 12.5% interest in the mine.[5]

By the mid 14th century, the mine had grown into a vital national resource, and a large part of the revenues for the Swedish state in the coming centuries would be from the mine. The then king, Magnus IV, visited the area personally and drafted a charter for mining operations, ensuring the financial interest of the sovereign.[6]

Methods

The principal method for extracting copper was heating the rock via large fires, known as fire-setting. When the rock cooled down, it would become brittle and crack, allowing manual tools such as wedges and sledge hammers to be brought to bear. After the ore had been transported out of the mine it was roasted to reduce sulfur content in open hearths. The thick, poisonous smoke produced would be a distinguishing feature of the Falun area for centuries. After the roasting, the ore was smelted; the output of which was a copper rich material. The cycle of roasting and smelting was repeated several times until crude copper was produced. This was the final output from the mine; further refinement took place at copper refineries elsewhere. This process was used without any major change for seven centuries, until the end of the 19th century.[7] It is likely that the methods and technology for fire-setting and drainage were imported from German mines, such as in the Harz Mountains.[8]

Free miners

The organizational structure of Falun Mine created under the 1347 charter was advanced for its time. Free miners owned shares of the operation, proportional to their ownership of copper smelters. The structure was precursor to modern joint stock companies, and Stora Enso, the modern successor to the old mining company, is often referred to as the oldest joint stock company still operational in the world.[3]

Golden era

In the 17th century, production capacity peaked. During this time, the output from the mine was used to fund various wars of Sweden during its great power era. The Privy Council of Sweden referred to the mine as the nation's treasury and stronghold. The point of maximum production occurred in 1650, with over 3,000 tonnes of copper produced.[2]

The mountain had been mined for nearly half a millennium towards the end of its golden era. Production had intensified in the preceding decades, and by 1687 the rock was crisscrossed by numerous shafts and cave-ins were not unusual. Great effort went into producing maps of the mine for navigation, but there was no overall organization nor any estimation of the strength of the mountain. In the summer of 1687, great rumblings could be heard regularly from the mountain. On Midsummer's Eve of that year, the dividing wall between the main pits and the foundations gave way, and a significant portion of the mine collapsed. This could easily have become a great catastrophe, killing and trapping the hundreds of men working in the mine, had it not occurred on Midsummer's Eve, one of the two days of the year on which the miners were not working, the other being Christmas.[9]

Life in the mine

Fires were lit at the end of the day to heat the ore and allowed to burn through the night. The next morning the fires would be put out and the ore broken loose. In this manner, the miners could advance about 1 m (3 ft) per month. The miners working the fires and breaking the rock were the best paid and most skilled. Hand barrows were used to transport the broken ore, in relays of about 20 m (70 ft) with multiple teams working long distances. This was usually the work newcomers were assigned to prove themselves. The work was hard and the mines very hot from the constant fires so it was not surprising that the miners were good customers of local drinking establishments. Drunkenness was considered quite normal for miners.[10]

Carl Linnaeus visited the mine and produced a vivid description of the life of the miners. He described that the miners climbed rickety ladders with sweat pouring from their bodies like "water from a bath". He continued: "The Falun Mine is one of the great wonders of Sweden but as horrible as hell itself". Linnaeus' description of the environment the miners worked in is as follows: "Soot and darkness surrounded them on all sides. Stones, gravel, corrosive vitriol, drips, smoke, fumes, heat, dust, were everywhere".[11]

Economic impact

Sweden had a virtual monopoly on copper which it retained throughout the 17th century. The only other country with a comparable copper output was Japan, but European imports from Japan were insignificant. In 1690, Erik Odhelius, a prominent metallurgist, was dispatched by the King to survey the European metal market. Although copper production had already begun to decline by the time he made his report, something Odhelius made no secret of, he stated, "For the production of copper Sweden has always been like a mother, and although in many places within and without Europe some copper is extracted it counts for nothing next to the abundance of Swedish copper".[12]

By modern standards, however, the output was not large. Peak production barely reached 3,000 tonnes of copper per year, falling to less than 2,000 tonnes by 1665; from 1710–1720 it was barely 1,000 tonnes per year. Present worldwide copper production is 18.3 million tons per year.[13]

Modern history

Copper production declined during the 18th century, and the mining company began diversifying. It supplemented copper extraction with iron and timber production. Production of the iconic falu red paint began in earnest. In the 19th century, iron and forest products continued to grow in their importance. In 1881 gold was discovered in Falun Mine, resulting in a short-lived gold rush. A total of 5 tonnes of gold would eventually be produced.

By the late 20th century, the mine was no longer economically viable. On December 8, 1992, the last shot was fired in the mine, and all commercial mining ceased. Today the mine is owned by the Stora Kopparberget foundation which operates the museum and tours.[14]

World heritage

In 2001 Falun Mine was selected as a UNESCO World Heritage site, one of 15 in Sweden. In addition to the mine itself, the world heritage area covers the town of Falun, including 17th century miners’ cottages, residential areas,[15] and Bergsmansbygden, a wider area that the free miners settled and in which they often built estates mirroring their wealth.[16]

Museum

The museum has around 100,000 visitors per year.[17] It displays the history of mining at Falun Mine through the centuries; including the production of minerals, models of machinery, tools, and the people at the mine. It also has a large collection of portraits, starting from the 17th century, of significant people at the mine.[18]

Notes

- ↑ "Mining Area of the Great Copper Mountain in Falun". Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- 1 2 "1600s - The period of greatness". Falu Gruva. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- 1 2 ICOMOS, p. 5

- ↑ Rydberg, pp. 9–11

- ↑ Rydberg, p. 12

- ↑ Rydberg, p. 13

- ↑ Rydberg, p. 14

- ↑ ICOMOS, p. 1

- ↑ Rydberg, p. 44

- ↑ Rydberg, pp. 43–44

- ↑ Kjellin, p. 124

- ↑ Heckscher, p. 87

- ↑ "Copper" (PDF). Mineral Commodity Summaries 2015. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ↑ "1900s and the end of the mining operation". Falu Gruva. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ↑ "The town of Falun". Falun World Heritage Site. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ "Homesteader estates". Falun World Heritage Site. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ Kjellin, p.126.

- ↑ "Mining Museum". Falu Gruva. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

References

- Forss, Tommy (1990). The Falun Mine. Falun: Copper Mine Museum.

- Rydberg, Sven (1979). Stora Kopparberg - 1000 years of an industrial activity. Gullers International AB. ISBN 91-85228-52-4.

- Kjellin, Margareta; Ericson, Nina (1999). Genuine Falun Red. Stockholm: Prisma. ISBN 91-518-4371-4.

- Heckscher, Eli Filip (1954). An economic history of Sweden, Volume 95. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-22800-6.

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) (2000), Mining Area of the Great Copper Mountain in Falun - Advisory Body Evaluation (PDF), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Coordinates: 60°35′56″N 15°36′44″E / 60.59889°N 15.61222°E