Fado

| Fado | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Portuguese music |

| Cultural origins | Early 19th-century Lisbon, Portugal |

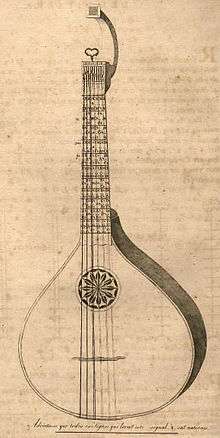

| Typical instruments |

Guitarra Portuguesa: Portuguese guitar |

| Derivative forms | Coimbra Fado |

Fado (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈfaðu]; "destiny, fate") is a music genre that can be traced to the 1820s in Lisbon, Portugal, but probably has much earlier origins. Fado historian and scholar Rui Vieira Nery states that "the only reliable information on the history of Fado was orally transmitted and goes back to the 1820s and 1830s at best. But even that information was frequently modified within the generational transmission process that made it reach us today."[1]

Although the origins are difficult to trace, today fado is commonly regarded as simply a form of song which can be about anything, but must follow a certain traditional structure. In popular belief, fado is a form of music characterized by mournful tunes and lyrics, often about the sea or the life of the poor, and infused with a sentiment of resignation, fatefulness and melancholia. This is loosely captured by the Portuguese word saudade, or "longing", symbolizing a feeling of loss (a permanent, irreparable loss and its consequent lifelong damage). This is similar to the character of the music genre Morna from Cape Verde, which may be historically linked to fado in its earlier form but has retained its rhythmic heritage. This connection to the music of a historic Portuguese urban and maritime proletariat (sailors, dock workers, port traders, etc.) can also be found in Brazilian Modinha and Indonesian Kroncong, although all these music genres subsequently developed their own independent traditions.

Famous singers of fado include Amália Rodrigues, Dulce Pontes, Carlos do Carmo, Mariza, Mafalda Arnauth, António Zambujo, Ana Moura, Camané, Helder Moutinho, Carminho, Mísia, Cristina Branco, Nathalie Pires, and Gisela João, Maja Milinkovic.

On 27 November 2011, fado was added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[2] It is one of two Portuguese music traditions part of the lists, the other being Cante Alentejano.[3]

Etymology

The word "fado" comes from the Latin word fatum,[4] from which the English word "fate" also originates.[5] The word is linked to the music genre itself and, although both meanings are approximately the same in the two languages, Portuguese speakers seldom utilize the word fado referring to destiny or fate. Nevertheless, many songs play on the double meaning, such as the Amália Rodrigues song "Com que voz", which includes the lyric "Com que voz chorarei meu triste fado" ("With what voice should I lament my sad fate/sing my sad fado?").[6]

The English-Latin term vates, the Scandinavian fata ("to compose music") and the French name fatiste (also meaning "poet") have been associated with the term fadista.[7][8]

History

Fado appeared during the early 19th century in Lisbon, and is believed to have its origins in the port districts such as Alfama, Mouraria and Bairro Alto.

There are many theories about the origin of fado. Some trace its origins or influences to "cantigas de amigo" (friends songs) and possibly ancient Moorish influence, but none conclusive.

Fado performers in the middle of the 19th century were mainly from urban working class and sailors, who not only sang, but also danced and beat the fado. During the second half of the 19th century, the African rhythms would become less important, and the performers became merely singers (fadistas).

The 19th century's most renowned fadista was Maria Severa.

More recently Amália Rodrigues, known as the "Rainha do Fado" ("Queen of Fado") was most influential in popularizing fado worldwide.[9] Fado performances today may be accompanied by a string quartet or a full orchestra.

Musicological aspects

Fado typically employs the Dorian mode, Ionian mode (natural major), sometimes switching between the two during a melody or verse change, more recently the Phrygian mode (common in Middle Eastern and Flamenco music), which is not considered a traditional feature of this genre.

A particular stylistic trait of fado is the use of rubato, where the music pauses at the end of a phrase and the singer holds the note for dramatic effect. The music uses double time rhythm and triple time (waltz style).

Varieties of fado

There are two main varieties of fado, namely those of the cities of Lisbon and Coimbra. The Lisbon style is more well known - alongside the status of Amália Rodrigues, while that of Coimbra is traditionally linked to the city's University and its style is linked to the medieval serenading troubadours. Modern fado is popular in Portugal, and has produced many renowned musicians. According to tradition, to applaud fado in Lisbon you clap your hands, while in Coimbra one coughs as if clearing one's throat.

Lisbon Fado

Early history

Born in the popular contexts of the 1800s Lisbon, fado was present in convivial and leisure moments. Happening spontaneously, its execution took place indoors or outdoors, in gardens, bullfights, retreats, streets and alley, taverns, cafés de camareiras and casas de meia-porta. Evoking urban emergence themes, singing the daily narratives, fado is profoundly related to social contexts ruled by marginality and transgression in a first phase, taking place in locations visited by prostitutes, faias, sailors, coachmen and marialvas. Often surprised in prison, its actors - the singers - are described in the faia figure, a fado singer guy, a bully of a rough and hoarse voice with tattoos and skilled with a flick knife who spoke using slang. As we will see, fado's association to society's most marginal spheres would definitely make the Portuguese intellectuals reject it profoundly.

Stating the communion of ludic spaces between the bohemian aristocracy and the most disfavoured fringes of Lisbon's population, the history of fado crystallized into myth the episode of the amorous relationship between the Count Vimioso and Maria Severa Onofriana (1820–1846), a Romani gypsy (Cigana) prostitute consecrated by her singing talents, who would soon transform into one of greatest myths of the history of fado. In successive image and sound reprises, the allusion to the involvement between a bohemian aristocrat with the fado singing prostitute would cross several sung poems and even the cinema and the theatre or the visual arts - beginning with the novel A Severa, by Júlio Dantas, published in 1901 and transported to the silver screen in 1931 - the first Portuguese sound film, directed by Leitão de Barros.

Fado would also conquer ground in festive events connected to the city's popular calendar, beneficence parties or cegadas - amateur and popular theatrical presentations generally performed by men on the street, in night feats, and popular associations. Although this sort of presentation was a famous entertaining form of Lisbon’s Carnival, enjoying popular support and often with strong intervening characters, the censorship regulation in 1927 would strongly but irreversibly contribute to the extinction of this type of show.

The Teatro de Revista, a sort of vaudeville theatre, a typical theatre genre from Lisbon born in 1851, would soon discover fado's potential. In 1870, fado began to appear in its musical scenes and from there gained a broader audience. Lisbon's social and cultural context, with its typical neighbourhoods and its own bohemian , assumed an absolute protagonism in Teatro de Revista. Having ascended the theatrical stage, fado would revitalise the Revista with the development of new themes and melodies. The music of the Teatro de Revista was orchestrated and filled with vocal refrains. Fado would be sung by famous actresses, and renowned fado singers singing their repertoires. Two different approaches to fado would become recorded in history: the danced fado stylized by Francis and the spoken fado of João Villaret. A central figure in the history of fado, Hermínia Silva gained fame in the theatre during the 1930s and 1940s, adding her gifts as singer to those of comic actress and revisteira. Fado's appropriation field broadened in the last quarter of the 19th century. About this time the form of the poetic "ten-verse stanza" stabilized: a quatrain consisting of four stanzas of ten verses each, from which fado would get its structure and later develop other variants. This is also the period when the Portuguese guitar - progressively diffused from the urban centres to the country's rural areas - became the companion instrument to a fado performance.

In the first decades of the 20th century, fado gradually diffused through Portuguese society and gained popularity with the publication of periodicals on the subject and the consolidation of a broad network of new performance venues that began incorporating fado in its agenda with a commercial perspective, fixating private casts which would often form embassies or artistic groups for tours. In parallel the relationship of fado with the theatre stages was consolidated and the performances by fado singers at Revistas musical scenes and operettas multiplied.

Estado Novo

In fact, the appearance of fado singing professional companies in the 1930s allowed promoting shows with great casts and their circulation in theatres north and south of the country, and even in international tours. That was the case of “Grupo Artístico de Fados”, with Berta Cardoso (1911–1997), Madalena de Melo (1903–1970), Armando Augusto Freire, (1891–1946) Martinho d’Assunção (1914–1992) and João da Mata, and "Grupo Artístico Propaganda do Fado", with Deonilde Gouveia (1900–1946), Júlio Proença (1901–1970) and Joaquim Campos (1899–1978), or “Troupe Guitarra de Portugal”, with Ercília Costa (1902–1985) and Alfredo Marceneiro (1891–1982) among others.

Although the first discographic records produced in Portugal date from the beginning of the 20th century, at this stage the national market was still very incipient since it was quite expensive to buy gramophones and records. Effectively, the fundamental conditions for recording sound appeared after the invention of the electric microphone in 1925. At the same time, gramophones started being made at more competitive prices. This created more favorable conditions for the market among the middle class.

In the context of the mediatization instruments of fado, TSF - wireless telegraphy - had a central importance in the first decades of the 20th century. Among the intense activity of radio broadcasting stations between 1925 and 1935, CT1AA, Rádio Clube Português, Rádio Graça and Rádio Luso - this last one quickly becoming popular for favouring fado. The broadcasts of the first Portuguese radio station, CT1AA, began in 1925. Investing in technical and logistic infrastructures which guaranteed it the expansion of its broadcast range and the broadcasts regularity, CT1AA of Abílio Nunes incorporated fado in its broadcasts, conquering a large group of listeners, including in the Portuguese emigration diaspora. With live feeds from the theaters and musical live presentations at the studios, CT1AA also promoted the broadcast of an experimental fado show directed by the Spanish guitar player Amadeu Ramin.

With the military coup of the 28 May 1926 and the implementation of previous censorship on public shows, the press and other publications, the urban song would suffer profound changes. In fact, in the following year the Decree Law Number 13 564 of 6 May 1927 globally regulated the show activities through extensive clauses; defending a “superior supervision of all the houses and show venues or public entertaining (...) by the General Inspection of Theatres and its delegates in behalf of the Public Instruction Ministry” on its 200 articles. Fado suffered unavoidable changes. The legal instrument regulated on the attribution of licenses to the companies which promoted shows at the most diversified venues, authorship rights, mandatory previous viewing of shows and sung repertoires, specific regulation for attributing the professional card, contracts, and tour traveling, among many other subjects. Significant mutations were so imposed on the performing venues, on the way interpreters presented themselves, and on the sung repertoires - stripped of any improvised character - cementing a professionalization process of several interpreters, instrument players, songwriters and composers, who were then performing at several venues before an increasing audience.

The hearing of fados would gradually become ritualized at fado houses, places which concentrated in the city’s historic neighbourhoods, mainly in Bairro Alto, especially since the 1930s. These transformations in the fado production would necessarily drift it apart from improvisation, losing some of its original performing contexts diversity and imposing the specialization of interpreters, authors and musicians. In parallel, the discographic and radio recordings proposed a triage of voices and performing practices that were imposed as models, thus limiting improvisation.

The next decade, the revivalism trends of the so-called typical features would definitely prevail, leading to a replication of the most genuine and picturesque in fado's performing venues.

Fado was present in the theater and the radio since their first moments and the same would happen in cinema. In fact, the appearance of sound films was marked by the presence of fado music, with the Portuguese cinema giving it special attention. The theme of the first Portuguese sound film, A Severa, directed by Leitão de Barros in 1931, was the misfortunes of the legendary Maria Severa Onofriana. As a central theme or a mere side note, fado accompanied cinema production until the 1970s. In fact, the Portuguese cinema showed particular interest in the fado universe in 1947 with O Fado, História de uma Cantadeira, starring Amália Rodrigues or in 1963, with O Miúdo da Bica, starring Fernando Farinha. Despite the starring role of Amália Rodrigues, the participation of artists like Fernando Farinha, Hermínia Silva, Berta Cardoso, Deolinda Rodrigues, Raul Nery and Jaime Santos in the Seventh Art are also noteworthy.[10]

While radio broadcasts brought fado to thousands of people, the inauguration of Rádio Televisão Portuguesa in 1957 – and after coverage became national in the mid-1970s - introduced the faces of performance artists to the general public. Stage sets representing fado themes were erected in the studios between 1959 and 1974, with live broadcasts of fado shows. Enjoying widespread diffusion on the Teatro de Revista stages since the last quarter of the 19th century, being promoted in the specialized entertainment press since the first decades of the 20th century, fado had increasingly broad exposure in radio, cinema, and television from the 1940s to 1960, often called the golden years of fado. The annual contest 'Grande Noite do Fado' began in 1953, lasting until the present. Gathering hundreds of candidates from several organizations and associations in the city, this contest is held at Coliseu dos Recreios, and is still an important event for Lisbon's fado tradition and the promotion of young amateurs hoping to acquire professional status.

The exponents of fado were at the time attached to a network of typical houses with regular casts. But now they had a broader working market with many new possibilities for recording, touring, and performing on radio and television. In parallel, there were performances by fado singers at the 'Serões para Trabalhadores', cultural events broadcast by radio and promoted by FNAT since 1942. Fado programmes were also promoted by the Secretariado Nacional de Informação, Cultura e Turismo which became the responsibility of the Emissora Nacional and Inspecção Geral dos Espectáculos in 1944. In the 1950s, the international success of Amália Rodrigues attracted the regime's attention with unfortunate consequences for her after its collapse.

The simplicity of fado's melodic structure accentuates particular vocal interpretations. With its strong emotionally evocative aspect, fado's lyrical poetry appeals to a communion between the interpreter, the musicians and the listeners. In quatrains or improvised quatrains, five-verse stanzas, six-verse stanzas, decasyllables and alexandrine verses, this popular poetry evokes themes related to love, luck, individual fate, and the city’s daily narrative.

And although the first fado lyrics were mostly anonymous, successively transmitted by oral tradition, this would definitely be reversed in the mid-1920s, when several popular poets emerged, such as Henrique Rego, João da Mata, Gabriel de Oliveira, Frederico de Brito, Carlos Conde and João Linhares Barbosa, who gave special attention to fado. In the 1950s, fado would definitely cross the path of erudite poetry in the voice of Amália Rodrigues. After the decisive contribution of the composer Alain Oulman, fado began singing texts of poets with academic education and published literary works, such as David Mourão-Ferreira, Pedro Homem de Mello, José Régio, Luiz de Macedo, and later Alexandre O.Neill, Sidónio Muralha, Leonel Neves and Vasco de Lima Couto, among many others.

The international spread of fado had begun in the mid-1930s as it became popular in the Porrtuguese African colonies and in Brazil, the preferred venues of some artists such as Ercília Costa, Berta Cardoso, Madalena de Melo, Armandinho, Martinho d’Assunção and João da Mata, among others. Notwithstanding cultural and language barriers, fado became an international phenomenon in the 1950s, especially with the rising popularity of Amália Rodrigues, fado's preeminent national and international star until her death in 1999.

Second Republic

.jpg)

The April 1974 Revolution established a democratic parliamentary republic in Portugal; its government was founded on the belief that implementing the principles of public liberty, mutual respect and guaranteed individual rights would lead to a more civically, politically and socially active citizenry. New global influences would be felt in Portugal progressively over the following decades, influences that affected fado's position in the Portuguese music market, still centred on popular music but absorbing many of the musical trends arising internationally.

In the years immediately after the revolution, a two year absence of the Grande Noite do Fado contest and a diminished presence in radio or television broadcasts testified to a public hostility towards fado that even Amália Rodrigues was not immune from, because of its association with the Estado Novo. Only when the democratic regime became stable in 1976 would fado regain its former place. The following year, the album Um Homem na Cidade was released by Carlos do Carmo, a central figure of fado's internationalization, who in a career spanning 45 years has continued to articulate the legitimate fado tradition.

As the ideological debate around fado gradually came to an end in the 1980s, the centrality of fado consenso in the Portuguese musical patrimony began to be recognized as the public showed a renewed interest in fado. The record industry re-issued classic recordings, fado was integrated into the popular musical circuits on a regional scale, a new generation of progressive interpreters appeared, and even singers and musicians from other genres became involved, including such figures as José Mário Branco, Sérgio Godinho, António Variações, Paulo de Carvalho, Rão Kyao, Ovelha Negra, A Naifa, O´queStrada, M-Pex, and Deolinda.[11]

Internationally there is also a renewed interest in local musical cultures. Amália Rodrigues and Carlos do Carmo are among fado's most recognized names in the record industry, the media and in live shows.

In the 1990s, fado began to assert its position on the international World Music circuits with Mísia and Cristina Branco. Camané is another emerging performer in fado's resurgence. In the 1990s and at the turn of the century a new generation of talented interpreters appeared: Teresa Salgueiro of Madredeus, Mafalda Arnauth, Katia Guerreiro, Maria Ana Bobone, Joana Amendoeira, Ana Moura, Ana Sofia Varela, Pedro Moutinho, Helder Moutinho, Gonçalo Salgueiro, António Zambujo, Miguel Capucho, Rodrigo Costa Félix, Patrícia Rodrigues, and Raquel Tavares.[12] On the international circuit, Marizahas won successive prizes in the World Music category.

Coimbra fado

This fado is closely linked to the academic traditions of the University of Coimbra and is exclusively sung by men; both the singers and musicians wear the academic outfit (traje académico): dark robe, cape and leggings. Dating to the troubadour tradition of medieval times, it is sung at night, almost in the dark, in city squares or streets. The most typical venues are the stairsteps of the Santa Cruz Monastery and the Old Cathedral of Coimbra. It is also customary to organize serenades where songs are performed before the window of a woman to be courted.

As in Lisbon, Coimbra fado is accompanied by the guitarra portuguesa and viola (classical guitar). The Coimbra guitar has evolved into an instrument different from that of Lisbon, with its own tuning, sound colouring, and construction. Artur Paredes, a progressive and innovative singer, revolutionised the tuning of the guitar and its accompaniment style to Coimbra fado. Artur Paredes was the father of Carlos Paredes, who followed in his father's footsteps and expanded on his work, making the Portuguese guitar an instrument known around the world.

In the 1950s, a new movement led the singers of Coimbra to adopt the ballad and folklore. They began interpreting lines of the great poets, both classical and contemporary, as a form of resistance to the Salazar dictatorship. In this movement names such as Adriano Correia de Oliveira and José Afonso (Zeca Afonso) had a leading role in popular music during the Portuguese revolution 1974.

Some of the most famous fados of Coimbra include: Fado Hilário, Saudades de Coimbra ("Do Choupal até à Lapa"), Balada da Despedida ("Coimbra tem mais encanto, na hora da despedida" - the first phrases are often more recognizable than the song titles), O meu menino é d'oiro, and Samaritana. The "judge-singer" Fernando Machado Soares is an important figure, being the author of some of those famous fados.

Curiously, it is not a Coimbra fado but a popular song which is the most known title referring to this city: Coimbra é uma lição, which had success with titles such as April in Portugal.

See also

- Fados - a 2007 movie about fado by Spanish director Carlos Saura

- List of fado musicians

References

- ↑ http://www.fnac.pt/Para-uma-Historia-do-Fado-Rui-Vieira-Nery/a306961

- ↑ "Fado, urban popular song of Portugal". UNESCO Culture Sector. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ↑ "Cante Alentejano, polyphonic singing from Alentejo, southern Portugal". unesco.org. UNESCO. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary: fado

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary: fate

- ↑ Richard Elliott (2010). Fado and the Place of Longing: Loss, Memory and the City. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 19, note 17. ISBN 978-0-7546-6795-7.

'Fado', as well as referencing a musical genre, is also the Portuguese word for 'fate', allowing a potential double meaning in many songs that use the word.

- ↑ CURSO DE HISTORIA DA LITTERATURA PORTUGUEZA

- ↑ Teófilo Braga. Epopêas da raça mosárabe

- ↑ Rohter, Larry (March 25, 2011). "Carving Out a Bold Destiny for Fado". The New York Times.

- ↑ Gabriela Cruz, 'The Suspended Voice of Amália Rodrigues'. In: Music in Print and Beyond, pp. 180-199. ISBN 9781580464161

- ↑ Michael Davis Arnold (June 2013). "Saudade, Duende, and Feedback: The Hybrid Voices of Twenty-First-Century Neoflamenco and Neofado". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on June 28, 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ↑ For an attempt to explain the aesthetics of fado at the beginning of the 21st century see Andreas Dorschel, 'Ästhetik des Fado.' In: Merkur 69 (2015), no. 2, pp. 79–86 (article online)

External links

- Mariza.com - Mariza, acclaimed fado artist from Portugal.

- * With Amalia to Stars - http://radojcicz.bloguedemusica.com/ intangible-cultural-heritage-%E2%80%93-unesco/ FADO: World’s Intangible Cultural Heritage – UNESCO - Portuguese American Journal

- Fado: Rodrigo Costa Félix’ style deeply grounded in tradition – Interview Portuguese American Journal

- NadiaRebelo.com - Nadia Rebelo, the young exponent of fado in Goa, Portugal and beyond.

![]() Media related to Fado at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fado at Wikimedia Commons