October Crisis

| October Crisis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War Quebec sovereignty movement | |||||||

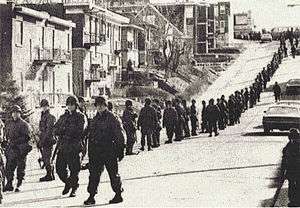

Troop movements during the surrender of the Chenier Cell | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 British diplomat kidnapped (later released) & 1 Canadian minister kidnapped & killed | ~30 arrested | ||||||

The October Crisis (French: La crise d'Octobre) occurred in October 1970 in the province of Quebec in Canada, mainly in the Montreal metropolitan area. Members of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) kidnapped the provincial cabinet minister Pierre Laporte and the British diplomat James Cross. In response, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the only peacetime use of the War Measures Act. The kidnappers murdered Laporte, and negotiations led to Cross's release and the kidnappers' exile to Cuba.

The Premier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa, and the Mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau, supported Trudeau's invocation of the War Measures Act, which limited civil liberties. The police were enabled with far-reaching powers, and they arrested and detained, without bail, 497 individuals, all but 62 of whom were later released without charges. The Quebec government also requested military aid to the civil power, and Canadian Forces deployed throughout Quebec; they acted in a support role to the civil authorities of Quebec.[1]

At the time, opinion polls throughout Canada, including in Quebec, showed widespread support for the use of the War Measures Act.[2] The response, however, was criticized at the time by prominent politicians such as René Lévesque and Tommy Douglas.[3]

The events of October 1970 galvanized support against the use of violence in efforts to gain Quebec sovereignty and accelerated the movement towards electoral means of attaining greater autonomy and independence,[4] including support for the sovereigntist Parti Québécois, which formed the provincial government in 1976.

Background

From 1963 to 1970 the Quebec nationalist group Front de libération du Québec detonated over 95 bombs.[5] While mailboxes—particularly in the affluent and predominantly Anglophone city of Westmount—were common targets, the largest single bombing was of the Montreal Stock Exchange on February 13, 1969, which caused extensive damage and injured 27 people. Other targets included Montreal City Hall, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, armed forces recruiting offices, railway tracks, and army installations. FLQ members, in a strategic move, had stolen several tons of dynamite from military and industrial sites, and, financed by bank robberies, they threatened through their official communication organ, known as La Cognée, that more attacks were to come.

By 1970, 23 members of the FLQ were in prison, including four convicted of murder. On February 26, 1970, two men in a panel truck – including Jacques Lanctôt – were arrested in Montreal when they were discovered with a sawed-off shotgun and a communique announcing the kidnapping of the Israeli consul. In June, police raided a home in the small community of Prévost, north of Montreal in the Laurentian Mountains, and found firearms, ammunition, 300 pounds (140 kg) of dynamite, detonators, and the draft of a ransom note to be used in the kidnapping of the United States consul.[6]

Timeline

- October 5: Montreal, Quebec: Two members of the "Liberation Cell" of the FLQ kidnap British Trade Commissioner James Cross from his home. The kidnappers are disguised as delivery men bringing a package for his recent birthday. Once the maid lets them in, they pull out a rifle and a revolver and kidnap Cross. This is followed by a communique to the authorities containing the kidnappers' demands, which include the exchange of Cross for "political prisoners", a number of convicted or detained FLQ members, and the CBC broadcast of the FLQ Manifesto. The terms of the ransom note are the same as those found in June for the planned kidnapping of the U.S. consul. At this time, the police do not connect the two.

- October 8: Broadcast of the FLQ Manifesto in all French- and English-speaking media outlets in Quebec.

- October 10: Montreal, Quebec: Members of the Chenier Cell approach the home of the Minister of Labour of the province of Quebec, Pierre Laporte, while he is playing football with his nephew on his front lawn. Members of the "Chenier cell" of the FLQ kidnap Laporte.

- October 11: The CBC broadcasts a letter from captivity from Pierre Laporte to the Premier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa.[7]

- October 12: General Gilles Turcot sends troops to patrol the Montreal region, by request of the federal government.[8] Lawyer Robert Lemieux is appointed by the FLQ to negotiate the release of James Cross and Pierre Laporte. The Quebec Government appoints Robert Demers.[9]

- October 13: Prime Minister Trudeau is interviewed by the CBC with respect to the military presence.[10] In a combative interview, Trudeau asks the reporter, Tim Ralfe, what he would do in his place. When Ralfe asks Trudeau how far he would go Trudeau replies, "Just watch me".

- October 14: Sixteen prominent Quebec personalities, including René Lévesque and Claude Ryan, call for negotiating "exchange of the two hostages for the political prisoners". FLQ's lawyer Robert Lemieux urges Université de Montréal (University of Montreal) students to boycott classes in support of FLQ.

- October 15: Quebec City: The negotiations between lawyers Lemieux and Demers are put to an end.[11] The Government of Quebec formally requests the intervention of the Canadian army in "aid of the civil power" pursuant to the National Defence Act. All three opposition parties, including the Parti Québécois, rise in the National Assembly and agree with the decision. On the same day, separatist groups are permitted to speak at the Université de Montréal. Robert Lemieux organizes a 3,000 student rally in Paul Sauvé Arena to show support for the FLQ; labour leader Michel Chartrand announces that popular support for FLQ is rising[7] and states "We are going to win because there are more boys ready to shoot members of Parliament than there are policemen."[12] The rally frightens many Canadians, who view it as a possible prelude to outright insurrection in Quebec.

- October 16: Premier Bourassa formally requests that the government of Canada grant the government of Quebec "emergency powers" that allow them to "apprehend and keep in custody" individuals. This results in the implementation of the War Measures Act, allowing the suspension of habeas corpus, giving wide-reaching powers of arrest to police. The City of Montreal had already made such a request the day before. These measures come into effect at 4:00 a.m. Prime Minister Trudeau makes a broadcast announcing the imposition of the War Measures Act.

- October 17: Montreal, Quebec: The Chenier cell of the FLQ announces that hostage Pierre Laporte has been executed. He was strangled, his body stuffed in the trunk of a car and abandoned in the bush near Saint-Hubert Airport, a few miles from Montreal. A communique to police advising that Pierre Laporte has been executed refers to him derisively as the "minister of unemployment and assimilation". In another communique issued by the "Liberation cell" holding James Cross, his kidnappers declare that they are suspending indefinitely the death sentence against him, that they will not release him until their demands are met, and that he will be executed if the "fascist police" discover them and attempt to intervene. The demands they make are: 1) The Publication of the FLQ manifesto. 2) The release of 23 political prisoners. 3) An airplane to take them to either Cuba or Algeria (both countries that they feel a strong connection to because of their struggle against colonialism and imperialism). 4) The re-hiring of the "gars de Lapalme". 5) A "voluntary tax" of 500,000 dollars to be loaded aboard the plane prior to departure. 6) The name of the informer who had sold out the FLQ activists earlier in the year.[13] Controversially, police reports not released to the public until 2010 state that Pierre Laporte was accidentally killed during a struggle. The FLQ subsequently wanted to use his death to its advantage by convincing the government that they should be taken seriously.[14]

- October 18: While denouncing the acts of "subversion and terrorism – both of which are so tragically contrary to the best interests of our people", columnist, politician, and future Premier of Quebec René Lévesque criticizes the War Measures Act: "Until we receive proof (of the size the revolutionary army) to the contrary, we will believe that such a minute, numerically unimportant fraction is involved, that rushing into the enactment of the War Measures Act was a panicky and altogether excessive reaction, especially when you think of the inordinate length of time they want to maintain this regime."[15]

- November 6: Police raid the hiding place of the FLQ's Chenier cell. Although three members escape the raid, Bernard Lortie is arrested and charged with the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte.

- December 4: Montreal, Quebec: After being held hostage for 62 days, kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross is released by the FLQ Liberation Cell after negotiations between lawyers Bernard Mergler and Robert Demers.[11][16] Simultaneously, the five known kidnappers, Marc Carbonneau, Yves Langlois, Jacques Lanctôt, Jacques Cossette-Trudel and his wife, Louise Lanctôt, are granted safe passage to Cuba by the government of Canada after approval by Fidel Castro. They are flown to Cuba by a Canadian Forces aircraft. Jacques Lanctôt is the same man who, earlier that year, had been arrested and then released on bail for the attempted kidnapping of the Israeli consul.

- December 23: Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau announces that all troops stationed in Quebec will be withdrawn by January 5th 1971.[17]

- December 28: Saint-Luc, Quebec: The three members of the Chenier Cell still at large, Paul Rose, Jacques Rose, and Francis Simard, are arrested after being found hiding in a 6 m tunnel in a rural farming community. They would later be charged with the kidnapping and murder of Pierre Laporte.

War Measures Act and military involvement

When CBC reporter Tim Ralfe asked how far he was willing to go to stop the FLQ, Trudeau replied: "Just watch me." Three days later, on October 16, the Cabinet under his chairmanship advised the Governor General to invoke the War Measures Act at the request of the Premier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa, and the Mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau. The War Measures Act gave sweeping powers of arrest and internment to the police. The provisions took effect at 4 a.m., and, shortly thereafter, hundreds of suspected FLQ members and sympathizers were rounded-up. In total 497 people were arrested, including singer Pauline Julien and her partner, future Quebec Minister Gérald Godin, poet Gaston Miron, union activist Michel Chartrand and journalist Nick Auf der Maur.

This act was imposed only after the negotiations with the FLQ had broken off and the Premier of Quebec was facing the next stage in the FLQ's agenda.[18]

At the time, opinion polls in Quebec and the rest of Canada showed overwhelming support for the War Measures Act;[19][20] in a December 1970 Gallup Poll, it was noted that 89% of English-speaking Canadians supported the introduction of the War Measures Act, and 86% of French-speaking Canadians supported its introduction. They respectively had 6% and 9% disapproving, the difference being undecided.[21] Since then, however, the government's use of the War Measures Act in peacetime has been a subject of debate in Canada as it gave police sweeping powers of arrest and detention.

Simultaneously, under provisions quite separate from the War Measures Act and much more commonly used, the Solicitor-General of Quebec requisitioned the deployment of the military from the Chief of the Defence Staff in accordance with the National Defence Act. Troops from Quebec bases and elsewhere in the country were dispatched, under the direction of the Sûreté du Québec (Quebec's provincial police force), to guard vulnerable points as well as prominent individuals at risk. This freed the police to pursue more proactive tasks in dealing with the crisis. The two named Canadian Forces operations were Operation Ginger to mount guards on government of Canada buildings and important residences outside of Quebec, and Operation Essay to provide aid to the civil power in Quebec.[22]

Outside Quebec, mainly in the Ottawa area, the federal government deployed troops under its own authority to guard federal offices and employees. The combination of the increased powers of arrest granted by the War Measures Act, and the military deployment requisitioned and controlled by the government of Quebec, gave every appearance that martial law had been imposed. A significant difference, however, is that the military remained in a support role to the civil authorities (in this case, Quebec authorities) and never had a judicial role. It still allowed for the criticism of the government and the Parti Québécois was able to go about its everyday business free of any restrictions, including the criticism of the government and the War Measures Act.[18] Nevertheless, the sight of tanks on the lawns of the federal parliament was disconcerting to many Canadians. Moreover, police officials sometimes abused their powers and detained without cause prominent artists and intellectuals associated with the sovereignty movement.[23]

The October Crisis was the only occasion in which the War Measures Act was invoked in peacetime. The FLQ was declared an unlawful association; this meant that under the War Measures Act the police had full power to arrest, interrogate and hold anyone they believed was associated with the FLQ. This meant that "A person who was a member to this group, acted or supported it in some fashion became liable to a jail term not to exceed five years. A person arrested for such a purpose could be held without bail for up to ninety days".[24] It is estimated that within the first 24 hours of the War Measures Act being put in place, police mobilized to arrest suspects of the unlawful organization. The police conducted 3000 searches and 497 people were detained.[25]

Along with this, the War Measures Act violated and limited many human rights of people being incarcerated; for example "Everyone arrested under the War Measures Act was denied due process. Habeas corpus (an individual's right to have a judge confirm that they have been lawfully detained) was suspended. The Crown could detain a suspect for seven days before charging him or her with a crime. In addition, the attorney general could order, before the seven days expired, that the accused be held for up to 21 days. The prisoners were not permitted to consult legal counsel, and many were held incommunicado."[26]

There were cases, however few, of people having cause to be upset by the method of their interrogation; however, the majority of those interviewed after had little cause to complain and several even commented on the courteous nature of the interrogations and searches.[18] In addition, the Quebec Ombudsman, Louis Marceau, was instructed to hear complaints of detainees, and the Quebec government agreed to pay damages to any person unjustly arrested. On February 3, 1971, John Turner, Minister of Justice of Canada, reported that 497 persons had been arrested under the War Measures Act, of whom 435 had already been released. The other 62 were charged, of which 32 were accused of crimes of such seriousness that a Quebec Superior Court judge refused them bail.

Aftermath

Pierre Laporte was eventually found to have been killed by his captors while James Cross was freed after 59 days as a result of negotiations with the kidnappers who requested exile to Cuba rather than facing trial in Quebec. The cell members responsible for Laporte's death were arrested and charged with kidnapping and first-degree murder after they returned.

The response by the federal and provincial governments to the incident still sparks controversy. This is the only time that the War Measures Act had been put in place during peacetime in Canada.[27] A few critics (most notably Tommy Douglas and some members of the New Democratic Party[28]) believed that Trudeau was being excessive in advising the use of the War Measures Act to suspend civil liberties and that the precedent set by this incident was dangerous. Federal Progressive Conservative leader Robert Stanfield initially supported Trudeau's actions, but later regretted doing so.[29] The size of the FLQ organization and the number of sympathizers in the public was not known. However, in its Manifesto, the FLQ stated: "In the coming year (Quebec Premier Robert) Bourassa will have to face reality; 100,000 revolutionary workers, armed and organized."[30] Given that declaration, along with seven years of bombings and the wording of their communiques throughout that time that strove to present an image of a powerful organization spread secretly throughout all sectors of society, the authorities took significant action.

The events of October 1970 marked a significant loss of support for the violent wing of the Quebec sovereigntist movement that had gained support over nearly ten years,[4] and increased support for political means of attaining independence, including support for the sovereigntist Parti Québécois, which went on to take power at the provincial level in 1976. After the defeat of the Meech Lake Accord, which sought to amend the Constitution of Canada to resolve the passage by a previous government of the Constitution Act 1982 without Quebec's ratification, a pro-independence political party, the Bloc Québécois, was also created at the federal level.

In 1988 the War Measures Act was replaced by the Emergencies Act and the Emergency Preparedness Act.

Cinema and television

- Action: The October Crisis of 1970 and Reaction: A Portrait of a Society in Crisis, two 1973 documentary films by Robin Spry.[31]

- Orderers (Les Ordres), a historical film drama, directed in 1974 and based on the events of the October Crisis and the War Measures Act; concerning the effect it had on people in Quebec.

- Quebec director Pierre Falardeau shot in 1994 a movie titled Octobre which tells a version of the October Crisis based on a book by Francis Simard.

- Nô is partially set in Montreal during the October Crisis and features fictional FLQ members planning a bombing.

- CBC Television produced a two-hour documentary program Black October in 2000, in which the events of the crisis were discussed in great detail. The program featured interviews with former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, former Quebec justice minister Jérôme Choquette, and others.

- La Belle province, 2001 documentary film by Ad Hoc Films Montreal. Tele-Quebec, on the events leading to the death of Pierre Laporte.

- L'Otage, 2004 documentary film by Ad Hoc Films Montreal. Tele-Quebec, Richard Cross, his wife and his daughter remember how they suffered during October 1970.

- Tout le monde en parlait « La crise d'Octobre I : L'engrenage » Radio Canada 2010. Documentary relating the events of October 1970.

- Tout le monde en parlait « La crise d'Octobre II : Le denouement » Radio Canada 2010. Documentary on the October Crisis 1970.

- An eight-part miniseries about some of the incidents of the October Crisis titled October 1970 was released on October 12, 2006.

- In the Mid-Atlantic Sports Network series Orioles Classics the footage shown of the 1970 World Series is the feed from the CBC. The World Series is often interrupted for updates on the "Cross Kidnapping".

- "Just watch me: A Trudeau musical" 2015 Play at the Vancouver Fringe Festival.

References

- ↑ John English, Just Watch Me: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau: 1968–2000 (2009). pp 86–91

- ↑ "Chronology of the October Crisis, 1970, and its Aftermath – Quebec History". Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ↑ "Top Ten Greatest Canadians – Tommy Douglas". Archived from the original on 2008-04-25. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- 1 2 Fournier, Louis. FLQ: Anatomy of an Underground Movement, pg. 256

- ↑ "The Globe and Mail: Series – Pierre Elliott Trudeau 1919–2000". Archived from the original on 2008-01-18. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

Seven people had died and dozens had been injured. In retrospect, it seems impossible, but one bomb was planted somewhere in Quebec every 10 days.

- ↑ "Chronology of the October Crisis, 1970, and its Aftermath – Quebec History". .marianopolis.edu. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- 1 2 Canada since 1945: power, politics ... - Google Books. Retrieved 2011-02-19 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Appendix D of “The October Crisis, 1970: An Insiders View”, by Prof. William Tetley. http://www.mcgill.ca/maritimelaw/crisis/

- ↑ Tetley, William. The October Crisis, 1970 : An Insider View, pg 202. Demers, Robert. "Memories of October 70 (2010)" https://sites.google.com/site/octobercrisis70/

- ↑ "The October Crisis: Civil Liberties Suspended | CBC Archives". Archives.cbc.ca. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- 1 2 Demers, Robert. "Memories of October 70 (2010)" https://sites.google.com/site/octobercrisis70/

- ↑ "The Globe and Mail: Series – Pierre Elliott Trudeau 1919–2000". Archived from the original on 2008-01-18. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ↑ FLQ: The Anatomy of an Underground Movement

- ↑ "Révélations sur la mort de Pierre Laporte" [Revelations on the murder of Pierre Laporte]. Radio Canada (in French). September 24, 2010. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Statement by René Lévesque on the War Measures Act - Quebec History". Faculty.marianopolis.edu. 1970-10-17. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ↑ Montreal Star interview of Bernard Mergler published December 7, 1970 http://www.tou.tv/tout-le-monde-en-parlait/S05E16 [archive]

- ↑ "Chronology of the October Crisis, 1970, and its Aftermath – Quebec History". .marianopolis.edu.

- 1 2 3 Tetley, William (2007). The October Crisis, 1970: An Insiders View. McGill-Queens University Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-7735-3118-1.

- ↑ "Chronology of the October Crisis, 1970, and its Aftermath – Quebec History". Retrieved 2008-04-13.

There was widespread editorial approval of the action taken by the federal government; only Claude Ryan, in Le Devoir, condemned it as did René Lévesque, leader of the Parti Québécois. Polls taken shortly afterwards, showed that there was as much as 92% approval for the action taken by the Federal government.

- ↑ "Chronology of the October Crisis, 1970, and its Aftermath – Quebec History". Retrieved 2008-04-13.

In a series of polls conducted over the next few weeks, public support for the course of action undertaken by the Government of Canada continued to be overwhelming (72 to 84% approval rate). In a poll conducted on December 19 by the Canadian Institute of Public Opinion, Canadians indicated that their opinion of Trudeau, Bourassa, Caouette and Robarts, who had all expressed strong support for the War Measures Act, was more favourable than before, while their view of Stanfield and Douglas, who had expressed reservations for the Act, was less favourable than previously.

- ↑ Tetley, William. The October Crisis, 1970: An Insider's View, pg. 103.

- ↑ http://www.archeion.ca/operation-ginger-and-operation-essay

- ↑ Belanger, Claude. "Chronology of the October Crisis, 1970, and its Aftermath - Quebec History". History Prof. Marianopolis College. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Tetley, William. "The Importance of the Quebec "October Crisis, 1970" to the "Quiet Revolution" in the Province of Quebec (and the rest of Canada (ROC) as well)". McGill University. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ Clement, Dominique (2008). "The October Crisis of 1970: Human Rights Abuses Under the War Measures Act" (PDF). The Journal of Canadian Studies. 42 (2). Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "Quebec terrorists FLQ kidnapped 2 & began the Oct crisis". Retrieved 2008-04-13.

Public opinion polls showed that nearly nine in 10 citizens – both Anglo and French-speaking – supported Trudeau's hardline tactics against the FLQ.

- ↑ "Top Ten Greatest Canadians – Tommy Douglas". Archived from the original on 2008-04-25. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

The decision to vote against the motion (which passed with a majority vote) was not viewed favourably; the NDP's approval rating dropped to seven per cent in public opinion polls. Still, Douglas maintained that Trudeau was going too far: "The government, I submit, is using a sledgehammer to crack a peanut."

- ↑ "Remembering Robert Stanfield: A Good-Humoured and Gallant Man" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-04-13.

That particular backing [of the War Measures Act] was Stanfield’s only regret in a long political life. He later admitted that he wished he’d joined his lone dissenting colleague, David MacDonald, who voted against the Public Order Temporary Measures Act when it came before the House that November.

- ↑ Marc James Léger (2011). Culture and Contestation in the New Century. Intellect Books. pp. 165–. ISBN 978-1-84150-426-1.

- ↑ Spry, Robin (1973). "Action: The October Crisis of 1970". Documentary film. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved 2009-10-05.

Further reading

- Guy Bouthillier and Édouard Cloutier. Trudeau's Darkest Hour: War Measures in Time of Peace | October 1970, Baraka Books, Montréal, 2010, 212 p. ISBN 978-1-926824-04-8.

- Coté, Robert (2003). Ma guerre contre le FLQ. Montreal: Trait d'union.

- Demers, Robert. "Memories of October 70 (2010)".

- Denis, Charles (2006). Robert Bourassa - La passion de la politique. Montreal: Fides.

- English, John (2009), Just Watch Me: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau: 1968-2000, Alfred A. Knopf Canada, ISBN 978-0-676-97523-9

- Fournier, Louis (1984). FLQ: the anatomy of an underground movement; translated by Edward Baxter. Toronto: NC Press.

- Haggart Ron & Golden Audrey (1971). Rumours of war. Toronto: New Press.

- Laurendeau, Marc (1975). Les Québécois violents. Montreal: Boreal.

- Munroe, H. D. "The October Crisis revisited: Counterterrorism as strategic choice, political result, and organizational practice." Terrorism and Political Violence 21.2 (2009): 288-305.

- Saywell, John, ed. (1971). Canadian Annual Review for 1970. University of Toronto Press. pp. 3–152., Detailed factual coverage

- Tetley, William. (2006) The October Crisis, 1970 : An Insiders View McGill-Queen's University Press ISBN 0-7735-3118-1

- "The Events Preliminary to the Crisis" in chronological order – 1960 to October 5, 1970

- "The October Crisis per se" in chronological order – October 5 to December 29, 1970

External links

- Historical Site dedicated to the Quebec Liberation Front (FLQ) from an "indépendantist" perspective. (in French)

- CBC Digital Archives – The October Crisis: Civil Liberties Suspended

- "Terrorism" from the Canadian Encyclopedia

- "War Measures Act Debate Oct 16, 1970" from the Douglas-Coldwell Foundation

- BBC World Service, Witness: The October Crisis in Canada, an interview with former journalist Vince Carlin about his experience of the crisis, first broadcast 16 October 2015.