Visual perception

| Psychology |

|---|

| Basic types |

| Applied psychology |

| Lists |

|

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment using light in the visible spectrum reflected by the objects in the environment.

The resulting perception is also known as visual perception, eyesight, sight, or vision (adjectival form: visual, optical, or ocular). The various physiological components involved in vision are referred to collectively as the visual system, and are the focus of much research in linguistics, psychology, cognitive science, neuroscience, and molecular biology, collectively referred to as vision science.

Visual system

The visual system in animals allows individuals to assimilate information from their surroundings. The act of seeing starts when the cornea and then the lens of the eye focuses light from its surroundings onto a light-sensitive membrane in the back of the eye, called the retina. The retina is actually part of the brain that is isolated to serve as a transducer for the conversion of light into neuronal signals. Based on feedback from the visual system, the lens of the eye adjusts its thickness to focus light on the photoreceptive cells of the retina, also known as the rods and cones, which detect the photons of light and respond by producing neural impulses. These signals are processed via complex feedforward and feedback processes by different parts of the brain, from the retina upstream to central ganglia in the brain.

Note that up until now much of the above paragraph could apply to octopuses, mollusks, worms, insects and things more primitive; anything with a more concentrated nervous system and better eyes than say a jellyfish. However, the following applies to mammals generally and birds (in modified form): The retina in these more complex animals sends fibers (the optic nerve) to the lateral geniculate nucleus, to the primary and secondary visual cortex of the brain. Signals from the retina can also travel directly from the retina to the superior colliculus.

The perception of objects and the totality of the visual scene is accomplished by the visual association cortex. The visual association cortex combines all sensory information perceived by the striate cortex which contains thousands of modules that are part of modular neural networks. The neurons in the striate cortex send axons to the extrastriate cortex, a region in the visual association cortex that surrounds the striate cortex.[1]

Study

The major problem in visual perception is that what people see is not simply a translation of retinal stimuli (i.e., the image on the retina). Thus people interested in perception have long struggled to explain what visual processing does to create what is actually seen.

Early studies

There were two major ancient Greek schools, providing a primitive explanation of how vision is carried out in the body.

The first was the "emission theory" which maintained that vision occurs when rays emanate from the eyes and are intercepted by visual objects. If an object was seen directly it was by 'means of rays' coming out of the eyes and again falling on the object. A refracted image was, however, seen by 'means of rays' as well, which came out of the eyes, traversed through the air, and after refraction, fell on the visible object which was sighted as the result of the movement of the rays from the eye. This theory was championed by scholars like Euclid and Ptolemy and their followers.

The second school advocated the so-called 'intro-mission' approach which sees vision as coming from something entering the eyes representative of the object. With its main propagators Aristotle, Galen and their followers, this theory seems to have some contact with modern theories of what vision really is, but it remained only a speculation lacking any experimental foundation. (In eighteenth-century England, Isaac Newton, John Locke, and others, carried the intromission/intromittist theory forward by insisting that vision involved a process in which rays—composed of actual corporeal matter—emanated from seen objects and entered the seer's mind/sensorium through the eye's aperture.)[2]

Both schools of thought relied upon the principle that "like is only known by like", and thus upon the notion that the eye was composed of some "internal fire" which interacted with the "external fire" of visible light and made vision possible. Plato makes this assertion in his dialogue Timaeus, as does Aristotle, in his De Sensu.[3]

Alhazen (965 – c. 1040) carried out many investigations and experiments on visual perception, extended the work of Ptolemy on binocular vision, and commented on the anatomical works of Galen.[4][5]

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) is believed to be the first to recognize the special optical qualities of the eye. He wrote "The function of the human eye ... was described by a large number of authors in a certain way. But I found it to be completely different." His main experimental finding was that there is only a distinct and clear vision at the line of sight—the optical line that ends at the fovea. Although he did not use these words literally he actually is the father of the modern distinction between foveal and peripheral vision.

Unconscious inference

Hermann von Helmholtz is often credited with the first study of visual perception in modern times. Helmholtz examined the human eye and concluded that it was, optically, rather poor. The poor-quality information gathered via the eye seemed to him to make vision impossible. He therefore concluded that vision could only be the result of some form of unconscious inferences: a matter of making assumptions and conclusions from incomplete data, based on previous experiences.[6]

Inference requires prior experience of the world.

Examples of well-known assumptions, based on visual experience, are:

- light comes from above

- objects are normally not viewed from below

- faces are seen (and recognized) upright.[7]

- closer objects can block the view of more distant objects, but not vice versa

- figures (i.e., foreground objects) tend to have convex borders

The study of visual illusions (cases when the inference process goes wrong) has yielded much insight into what sort of assumptions the visual system makes.

Another type of the unconscious inference hypothesis (based on probabilities) has recently been revived in so-called Bayesian studies of visual perception.[8] Proponents of this approach consider that the visual system performs some form of Bayesian inference to derive a perception from sensory data. However, it is not clear how proponents of this view derive, in principle, the relevant probabilities required by the Bayesian equation. Models based on this idea have been used to describe various visual perceptual functions, such as the perception of motion, the perception of depth, and figure-ground perception.[9][10] The "wholly empirical theory of perception" is a related and newer approach that rationalizes visual perception without explicitly invoking Bayesian formalisms.

Gestalt theory

Gestalt psychologists working primarily in the 1930s and 1940s raised many of the research questions that are studied by vision scientists today.

The Gestalt Laws of Organization have guided the study of how people perceive visual components as organized patterns or wholes, instead of many different parts. "Gestalt" is a German word that partially translates to "configuration or pattern" along with "whole or emergent structure". According to this theory, there are eight main factors that determine how the visual system automatically groups elements into patterns: Proximity, Similarity, Closure, Symmetry, Common Fate (i.e. common motion), Continuity as well as Good Gestalt (pattern that is regular, simple, and orderly) and Past Experience.

Analysis of eye movement

During the 1960s, technical development permitted the continuous registration of eye movement during reading[11] in picture viewing[12] and later in visual problem solving[13] and when headset-cameras became available, also during driving.[14]

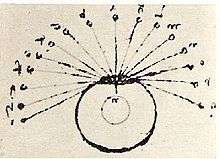

The picture to the right shows what may happen during the first two seconds of visual inspection. While the background is out of focus, representing the peripheral vision, the first eye movement goes to the boots of the man (just because they are very near the starting fixation and have a reasonable contrast).

The following fixations jump from face to face. They might even permit comparisons between faces.

It may be concluded that the icon face is a very attractive search icon within the peripheral field of vision. The foveal vision adds detailed information to the peripheral first impression.

It can also be noted that there are three different types of eye movements: vergence movements, saccadic movements and pursuit movements. Vergence movements involve the cooperation of both eyes to allow for an image to fall on the same area of both retinas. This results in a single focused image. Saccadic movements is the type of eye movement that makes jumps from one position to another position and is used to rapidly scan a particular scene/image. Lastly, pursuit movement is smooth eye movement and is used to follow objects in motion.[15]

Face and object recognition

There is considerable evidence that face and object recognition are accomplished by distinct systems. For example, prosopagnosic patients show deficits in face, but not object processing, while object agnosic patients (most notably, patient C.K.) show deficits in object processing with spared face processing.[16] Behaviorally, it has been shown that faces, but not objects, are subject to inversion effects, leading to the claim that faces are "special".[16][17] Further, face and object processing recruit distinct neural systems.[18] Notably, some have argued that the apparent specialization of the human brain for face processing does not reflect true domain specificity, but rather a more general process of expert-level discrimination within a given class of stimulus,[19] though this latter claim is the subject of substantial debate. Using fMRI and electrophysiology Doris Tsao and colleagues described brain regions and a mechanism for face recognition in macaque monkeys.[20]

The cognitive and computational approaches

In the 1970s, David Marr developed a multi-level theory of vision, which analyzed the process of vision at different levels of abstraction. In order to focus on the understanding of specific problems in vision, he identified three levels of analysis: the computational, algorithmic and implementational levels. Many vision scientists, including Tomaso Poggio, have embraced these levels of analysis and employed them to further characterize vision from a computational perspective.

The computational level addresses, at a high level of abstraction, the problems that the visual system must overcome. The algorithmic level attempts to identify the strategy that may be used to solve these problems. Finally, the implementational level attempts to explain how solutions to these problems are realized in neural circuitry.

Marr suggested that it is possible to investigate vision at any of these levels independently. Marr described vision as proceeding from a two-dimensional visual array (on the retina) to a three-dimensional description of the world as output. His stages of vision include:

- A 2D or primal sketch of the scene, based on feature extraction of fundamental components of the scene, including edges, regions, etc. Note the similarity in concept to a pencil sketch drawn quickly by an artist as an impression.

- A 2½ D sketch of the scene, where textures are acknowledged, etc. Note the similarity in concept to the stage in drawing where an artist highlights or shades areas of a scene, to provide depth.

- A 3 D model, where the scene is visualized in a continuous, 3-dimensional map.[21]

Marr's 2.5D sketch assumes that a depth map is constructed, and that this map is the basis of 3D shape perception. However, both stereoscopic and pictorial perception, as well as monocular viewing, make clear that the perception of 3D shape precedes, and does not rely on, the perception of the depth of points. It is not clear how a preliminary depth map could, in principle, be constructed, nor how this would address the question of figure-ground organization, or grouping. The role of perceptual organizing constraints, overlooked by Marr, in the production of 3D shape percepts from binocularly-viewed 3D objects has been demonstrated empirically for the case of 3D wire objects, e.g.[22] For a more detailed discussion, see Pizlo (2008).[23]

Transduction

Transduction is the process through which energy from environmental stimuli is converted to neural activity for the brain to understand and process. The back of the eye contains three different cell layers: photoreceptor layer, bipolar cell layer and ganglion cell layer. The photoreceptor layer is at the very back and contains rod photoreceptors and cone photoreceptors. Cones are responsible for color perception. There are three different cones: red, green and blue. Rods, are responsible for the perception of objects in low light.[24] Photoreceptors contain within them a special chemical called a photopigment, which are embedded in the membrane of the lamellae; a single human rod contains approximately 10 million of them. The photopigment molecules consist of two parts: an opsin (a protein) and retinal (a lipid).[25] There are 3 specific photopigments (each with their own color) that respond to specific wavelengths of light. When the appropriate wavelength of light hits the photoreceptor, its photopigment splits into two, which sends a message to the bipolar cell layer, which in turn sends a message to the ganglion cells, which then send the information through the optic nerve to the brain. If the appropriate photopigment is not in the proper photoreceptor (for example, a green photopigment inside a red cone), a condition called color vision deficiency will occur.[26]

Opponent process

Transduction involves chemical messages sent from the photoreceptors to the bipolar cells to the ganglion cells. Several photoreceptors may send their information to one ganglion cell. There are two types of ganglion cells: red/green and yellow/blue. These neuron cells constantly fire—even when not stimulated. The brain interprets different colors (and with a lot of information, an image) when the rate of firing of these neurons alters. Red light stimulates the red cone, which in turn stimulates the red/green ganglion cell. Likewise, green light stimulates the green cone, which stimulates the red/green ganglion cell and blue light stimulates the blue cone which stimulates the yellow/blue ganglion cell. The rate of firing of the ganglion cells is increased when it is signaled by one cone and decreased (inhibited) when it is signaled by the other cone. The first color in the name of the ganglion cell is the color that excites it and the second is the color that inhibits it. i.e.: A red cone would excite the red/green ganglion cell and the green cone would inhibit the red/green ganglion cell. This is an opponent process. If the rate of firing of a red/green ganglion cell is increased, the brain would know that the light was red, if the rate was decreased, the brain would know that the color of the light was green.[26]

Artificial visual perception

Theories and observations of visual perception have been the main source of inspiration for computer vision (also called machine vision, or computational vision). Special hardware structures and software algorithms provide machines with the capability to interpret the images coming from a camera or a sensor. Artificial Visual Perception has long been used in the industry and is now entering the domains of automotive and robotics.[27][28]

See also

Vision deficiencies or disorders

Related disciplines

References

- ↑ Carlson, Neil R. (2013). "6". Physiology of Behaviour (11th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA: Pearson Education Inc. pp. 187–189. ISBN 978-0-205-23939-9.

- ↑ Swenson, Rivka. (Spring/Summer 2010). Optics, Gender, and the Eighteenth-Century Gaze: Looking at Eliza Haywood’s Anti-Pamela. The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation, 51.1-2, 27-43.

- ↑ Finger, Stanley (1994). Origins of neuroscience: a history of explorations into brain function. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506503-4. OCLC 27151391.

- ↑ Howard, I (1996). "Alhazen's neglected discoveries of visual phenomena". Perception. 25 (10): 1203–1217. PMID 9027923. doi:10.1068/p251203.

- ↑ Khaleefa, Omar (1999). "Who Is the Founder of Psychophysics and Experimental Psychology?". American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences. 16 (2): 1–26.

- ↑ von Helmholtz, Hermann (1925). Handbuch der physiologischen Optik. 3. Leipzig: Voss.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hunziker, (2006) Im Auge des Lesers: foveale und periphere Wahrnehmung – vom Buchstabieren zur Lesefreude [In the eye of the reader: foveal and peripheral perception – from letter recognition to the joy of reading] Transmedia Stäubli Verlag Zürich 2006 ISBN 978-3-7266-0068-6

- ↑ Stone, JV (2011). "Footprints sticking out of the sand. Part 2: children's Bayesian priors for shape and lighting direction". Perception. 40 (2): 175–90. PMID 21650091. doi:10.1068/p6776.

- ↑ Mamassian, Pascal; Landy, Michael; Maloney, Laurence T. (2002). "Bayesian Modelling of Visual Perception". In Rao, Rajesh P. N.; Olshausen, Bruno A.; Lewicki, Michael S. Probabilistic Models of the Brain: Perception and Neural Function. Neural Information Processing. MIT Press. pp. 13–36. ISBN 978-0-262-26432-7.

- ↑ A Primer on Probabilistic Approaches to Visual Perception

- ↑ Taylor, Stanford E. (November 1965). "Eye Movements in Reading: Facts and Fallacies". American Educational Research Journal. 2 (4): 187–202. JSTOR 1161646. doi:10.2307/1161646.

- ↑ Yarbus, A. L. (1967). Eye movements and vision, Plenum Press, New York

- ↑ Hunziker, H. W. (1970). "Visuelle Informationsaufnahme und Intelligenz: Eine Untersuchung über die Augenfixationen beim Problemlösen" [Visual information acquisition and intelligence: A study of the eye fixations in problem solving]. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Psychologie und ihre Anwendungen (in German). 29 (1/2).

- ↑ Cohen, A. S. (1983). "Informationsaufnahme beim Befahren von Kurven, Psychologie für die Praxis 2/83" [Information recording when driving on curves, psychology in practice 2/83]. Bulletin der Schweizerischen Stiftung für Angewandte Psychologie.

- ↑ Carlson, Neil R.; Heth, C. Donald; Miller, Harold; Donahoe, John W.; Buskist, William; Martin, G. Neil; Schmaltz, Rodney M. (2009). Psychology the Science of Behaviour. Toronto Ontario: Pearson Canada. pp. 140–1. ISBN 978-0-205-70286-2.

- 1 2 Moscovitch, Morris; Winocur, Gordon; Behrmann, Marlene (1997). "What Is Special about Face Recognition? Nineteen Experiments on a Person with Visual Object Agnosia and Dyslexia but Normal Face Recognition". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 9 (5): 555–604. PMID 23965118. doi:10.1162/jocn.1997.9.5.555.

- ↑ Yin, Robert K. (1969). "Looking at upside-down faces". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 81 (1): 141–5. doi:10.1037/h0027474.

- ↑ Kanwisher, Nancy; McDermott, Josh; Chun, Marvin M. (June 1997). "The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception". The Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (11): 4302–11. PMID 9151747.

- ↑ Gauthier, Isabel; Skudlarski, Pawel; Gore, John C.; Anderson, Adam W. (February 2000). "Expertise for cars and birds recruits brain areas involved in face recognition". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (2): 191–7. PMID 10649576. doi:10.1038/72140.

- ↑ Chang, Le; Tsao, Doris Y. (2017-06-01). "The Code for Facial Identity in the Primate Brain". Cell. 169 (6): 1013–1028.e14. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 28575666. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.011.

- ↑ Marr, D (1982). Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information. MIT Press.

- ↑ Rock & DiVita, 1987; Pizlo and Stevenson, 1999

- ↑ 3D Shape, Z. Pizlo (2008) MIT Press)

- ↑ Hecht, Selig (1937-04-01). "Rods, Cones, and the Chemical Basis of Vision". Physiological Reviews. 17 (2): 239–290. ISSN 0031-9333.

- ↑ Carlson, Neil R. (2013). "6". Physiology of Behaviour (11th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA: Pearson Education Inc. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-205-23939-9.

- 1 2 Carlson, Neil R.; Heth, C. Donald (2010). "5". Psychology the science of behaviour (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA: Pearson Education Inc. pp. 138–145. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4.

- ↑ Barghout, Lauren, and Lawrence W. Lee. "Perceptual information processing system". U.S. Patent Application 10/618,543, filed July 11, 2003.

- ↑ Barghout, Lauren. "System and Method for edge detection in image processing and recognition". WIPO Patent No. 2007044828. 20 Apr. 2007.

Further reading

- Von Helmholtz, Hermann (1867). Handbuch der physiologischen Optik. 3. Leipzig: Voss. Quotations are from the English translation produced by Optical Society of America (1924–25): Treatise on Physiological Optics.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vision |

- The Organization of the Retina and Visual System

- Effect of Detail on Visual Perception by Jon McLoone, the Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- The Joy of Visual Perception Resource on the eye's perception abilities.

- VisionScience. Resource for Research in Human and Animal Vision A collection of resources in vision science and perception.

- Vision and Psychophysics.

- Visibility in Social Theory and Social Research. An inquiry into the cognitive and social meanings of visibility.

- Vision Scholarpedia Expert articles about Vision

.jpg)