Expulsion of Jews from Spain

The expulsion of the Jews from Spain was ordered in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs ruling Castile and Aragon through the Edict of Granada with the purpose, according to the decree, of preventing them from influencing "New Christians", Jews and their descendants who had under duress converted to Christianity. The decision to expel the Jews—or to prohibit the practice of Judaism[1]—followed the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition in the Crowns of Castile and Aragon to weed out the conversos who continued practising their old faith. Historian Julio Valdeón wrote, "undoubtedly the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian site is one of the most controversial issues of all that have happened throughout the history of Spain". French hispanist Joseph Pérez highlighted the similarities that exist between this expulsion and the persecution of the Jews in Hispania visigoda almost a thousand years earlier.

In 2015 the Spanish Parliament passed a law recognizing as Spanish those presumed to be descendants of the Jews expelled in 1492, thereby annulling the consequences of that expulsion.

Background

Jews in the peninsular medieval Christian states

Until the fourteenth century the Jews who lived under the Muslim caliphates of Al-Andalus were tolerated.

The January 2, 1492, the Catholic Monarchs conquered the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada. The last Muslim king, Boabdil, withdrew to the Alpujarras after almost 800 years of Muslim rule were ended by the Reconquista.

A letter sent by the Catholic Monarchs to the Council of Bilbao in 1490 stated that under canon law and according to the laws of the kingdoms, the Jews are tolerated and allowed to live in the kingdoms as subjects and vassals.[2] Joseph Pérez said "one must discard the commonly accepted idea of a Spain where members of the three religions of the Book—Christians, Muslims and Jews—would have lived together peacefully during the first two centuries of Al-Andalus, and later in the Christian Reconquest of Spain in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Tolerance implies not discriminating against minorities and respecting their difference, and between the eighth and fifteenth centuries we find nothing on the peninsula like tolerance." He states that communities of Christians, Jews and Muslims had never lived In the Christian kingdoms.[3] According to Henry Kamen, Jews and Muslims were treated "with contempt".[4] And the Jews were treated with disdain. Three communities "lived separate stocks."[5]

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Christian anti-Judaism in the medieval West was intensified, which is reflected in the harsh anti-Jewish measures agreed in the Lateran Council celebrated in 1215 at the behest of the Pope Innocent III. The peninsular Christian kingdoms were by no means foreign to the growth of increasingly belligerent anti-Judaism—in the Castilian code of Siete Partidas it was said that the Jews lived among Christians "so that their presence would remind that they descended from those who crucified Our Lord Jesus Christ"—but the kings continued to "protect" the Jews for the important role they played in their kingdoms.[6]

In the fourteenth century the period of "tolerance" towards the Jews was over, passing into a phase of increasing conflicts. According to Joseph Perez, "the changing times are not the mentalities, the circumstances. The good times of Spain of the three religions had coincided with a phase of territorial, demographic and economic expansion, Jews and Christians did not compete in the labor market: both one and the other contributed to the general prosperity and shared their benefits. The militant of the Church and the friars hardly found an echo. Of the fourteenth century, the wars and natural catastrophes that precede and follow the Black Plague create a new situation. ... [People] believe themselves to be the victim of a curse, punished for sins they would have committed. It invites the faithful to repent, to change their behavior and to return to God. This is when the presence of the "deicidal people" among Christians is considered scandalous.[7]

The Jewish massacres of 1391 and its consequences

The first wave of violence against the Jews in the Iberian Peninsula occurred in the Kingdom of Navarre as a consequence of the arrival in 1321 of the crusade of the shepherds from the other side of the Pyrenees. The Jewry of Pamplona and Estella are massacred. Two decades later the impact of the Black Death of 1348 provokes assaults on the juderías of several places, especially those of Barcelona and other places in the Principality of Catalonia. In the Crown of Castile anti-Jewish violence is closely related to the Civil War of the reign of Pedro I in which the side that supported Enrique de Trastámara used anti-Judaism as a propaganda weapon, and the pretender accused his stepbrother, King Peter, of favoring the Jews. Thus the first slaughter of Jews, in Toledo in 1355, was carried out by the supporters of Enrique de Trastámara when they entered the city. The same happened eleven years later when they occupied Briviesca. In Burgos, Jews who could not pay the large tribute imposed on them in 1366 were reduced to slavery and sold. In Valladolid the Jewry was assaulted in 1367 to the shout of "Long live King Henry!". There were no deaths, but the synagogues were burned down.[8]

But the great catastrophe for the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula took place in 1391 when massacres took place in the juderías of the Crowns of Castile and of Aragon. The assaults, the fires, the looting and the massacres begin in June in Seville, where Fernando Martínez, archdeacon of Écija, taking advantage of the power vacuum created by the death of the archbishop of Seville, hardened his preaching against the Jews that had begun in 1378, and ordered the overthrow of the synagogues and requisitioning of prayer books. In January of 1391, a first attempt of assault on the Jewish quarter was avoided by the municipal authorities, but in June hundreds of Jews were murdered, their houses ransacked, and the synagogues converted into churches. Some Jews managed to escape; others, terrified, asked to be baptized.[9][10]

From Seville anti-Jewish violence extended throughout Andalusia, and then extended to Castile. In August it reached the Crown of Aragon. Murders, looting and fires took place everywhere. Many of the Jews who survived fled, many to the kingdoms of Navarre and of Portugal, France, and North Africa. Others accepted baptism to avoid death. The number of victims is difficult to know. About 400 Jews were murdered in Barcelona; in Valencia 250; In Lérida 68 ... [11][12]

After the massacres of 1391, anti-Jewish measures were intensified: in 1411 Castile ordered that Jews wear a red badge sewn to their clothing. In the Crown of Aragon the possession of the Talmud was declared unlawful, and the number of synagogues per aljama is limited to one. In addition, the mendicant orders, with the support of the monarchs, intensified their campaign of proselytism, in which Valencian Vincent Ferrer played a prominent part, to convert Jews to Christianity. It was also decreed that Jews were obliged to attend three sermons every year. As a result of the massacres of 1391 and the measures that followed, by 1415 more than half of the Jews of Castile and Aragon had renounced the Mosaic law and had been baptized, including many rabbis and important members of the community.[13]

Jews in the fifteenth century

After the massacres of 1391 and the preaching that followed them, by 1415 scarcely a hundred thousand Jews continued to practice their religion in the crowns of Castile and Aragon. Joseph Perez said, "Spanish Judaism will never recover from this catastrophe." The Jewish community "came out of the crisis not only physically diminished but morally and intellectually shattered".[14]

In the Crown of Aragon, Judaism in important places such as Barcelona, Valencia and Palma virtually disappeared—in 1424 the Barcelona Jewry was abolished because it was considered unnecessary—[15] and only the Zaragoza one remained. In Castile aljamas once flourishing such as those of Seville, Toledo or Burgos lost much of their members; in 1492, the year of the expulsion, in the Crown of Aragon only a quarter of the former number of Jews remained. The famous Jewish community of Gerona, for example, was left with only 24 families. In the Crown of Castile not 80,000 were left. In Seville before the revolts of 1391 there were about 500 Jewish families. According to Joseph Perez, at the time of the expulsion there were less than 150,000 Jews, distributed in 35 aljamas of the Crown of Aragon and 216 in the Crown of Castile. In both Crowns it was observed that the Jews had left the great cities and lived in the small and the rural areas, less exposed "to the excesses of the Christians."[16]

After the critical period of 1391-1415, the pressure on Jews recovering their synagogues and books confiscated decreased, and they became able to avoid certain obligations such as carrying the red ribbon or attending friars' sermons. They could also reconstruct the internal organization of the aljamas and their religious activities, thanks to the agreements reached by the procurators of the aljamas gathered in Valladolid in 1432 and sanctioned by the king, which means that "the Crown of Castile accepts again officially that a minority of its subjects has another religion than the Christian one and recognizes the right of this minority to exist legally, with a legal status." "In this way the Jewish community is rebuilt with the approval of the crown." Abraham Beneviste, who presided over the meeting of Valladolid, was appointed court rabbi with authority over all the Jews of the kingdom, and at the same time as delegate of the king over them.[17]

During the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, in the last quarter of the 15th century, many Jews lived in rural villages and engaged in agricultural activities. Crafts and trade were not monopolized—international trade had passed into the hands of converts. While Jews continued to trade as money-lenders, the number of Christian lenders had increased a lot. Jews also continued to collect royal, ecclesiastical and seigniorial rents, but their importance had also diminished—in Castile they were only in charge of a quarter of the revenues. However, in the court of Castile—but not Aragon—Jews held important administrative and financial positions. Abraham Senior was from 1488 treasurer-major of the Holy Brotherhood, a key organism in the financing of the war of Grenada, and also chief rabbi of Castile. Yucé Abravanel was "A greater collector of the service and mountaineering of the herds, one of the more healthy income and greater yield of the Crown of Castile."[18] However, according to Joseph Perez, the role of the Jews in the court must not be exaggerated. "The truth was that the state could do without the Jews, both in the bureaucratic apparatus and in the management of the estate."[19]

We must therefore reject the claim that the Hebrew community at the end of the fifteenth century was immensely rich and influential. "In fact, the Spanish Jews at the time of their expulsion did not form a homogeneous social group. There were among them classes as in Christian society, a small minority of very rich and well-placed men, together with a mass of small people: Farmers, artisans, shopkeepers."[20] What united them was that they practiced the same faith, different from the one recognized, which made them a separate community within the monarchy and which was "property" of the crown which thereby protected them.[21] In a letter dated 7 July, 1477, addressed to the authorities of Trujillo, where incidents had occurred against the Jews, Queen Isabella I of Castile, after putting the aljama under her protection and prohibiting all type of oppression or humiliation against its members, states:[22]

All the Jews of my kingdoms are mine and are under my protection, and it is for me to defend and protect them and to keep them in justice.

Thus, the Jews "formed not a State in the State, but rather a micro-society next to the majority Christian society, with an authority [the rabbi greater] that the crown delegated to him over its members." The aljamas were organized internally with a wide margin of autonomy. They designated by lottery the council of elders that governed the life of the community; collecting their own taxes for the maintenance of worship, synagogues, and rabbinical teaching; lived under the norms of Jewish law, and had their own courts that understood all cases in civil matters - from the Cortes de Madrigal of 1476 criminal cases had passed to the royal courts. But Jews did not enjoy the fullness of civil rights: they had a specific tax system far more burdensome than that of Christians and were excluded from positions that could confer authority on Christians.[23]

The situation in which the Jews lived, according to Joseph Perez, posed two problems: "as subjects and vassals of the king, the Jews had no guarantee for the future - the monarch could at any time close the autonomy of the aljamas or require new Most important taxes-"; and, above all, "in these late years of the Middle Ages, when a state of modern character is being developed, there could be no question of a problem of immense importance: was the existence of separate and autonomous communities compatible with the demands of A modern state? This was the real question."[24]

The "converso problem" and the creation of the Inquisition

In the fifteenth century, the main problem stopped being the Jews to become the conversos, whose number according to Joseph Perez would probably be close to two hundred thousand people. Christian convert was applied to the Jews who had been baptized and their descendants. As many of them had done it by force they were always looked upon with distrust by those who will call themselves Old Christians.[25] In the fifteenth century the positions abandoned by the Jews were mostly occupied by the converts, who concentrated there where the Jewish communities had flourished before 1391. They dealt with the activities formerly performed by the Jews - trade, the handicraft - and now with the added advantage that as Christians they can access trades and professions that were previously forbidden to the Jews. Some even enter the clergy becoming canon so prior is[26] and even bishops.[27]

The social rise of the converts was viewed with suspicion by the "old" Christians, a resentment that was accentuated by the conscience on the part of those who had a differentiated identity, proud of being Christians and having Jewish ancestry, which was the lineage of Christ. Thus popular revolts broke out against the converts between 1449 and 1474, when in Castile lived a period of economic difficulties and political crisis (especially during the civil war of the reign of Henry IV). The first and most important of these revolts was the one that took place in 1449 in Toledo, during which a "Judgment-Statute" was approved that prohibited the access to the municipal positions of "no confesso of the lineage of the Jews" - an antecedent of the following blood-cleaning statutes of the following century. The origin of the revolts was economic in Andalusia especially there was a situation of hunger, aggravated by an epidemic of plague - and in principle "not directed especially against the converts." It is the parties and the demagogues that take advantage of the exasperation of the people and direct it against the converts."[28]

In order to justify the attacks on the converts, it is affirmed that they are false Christians and that they are still practicing the Jewish religion in secret. According to Joseph Perez, it is a proven fact that, among those who converted to escape the blind furor of the masses in 1391, or by the pressure of the proselytizing campaigns of the early fifteenth century, some clandestinely returned to their old faith when It seemed that the danger had passed, of which it is said that Judaízan. The accusation of Crypto-Judaism becomes more plausible when some cases of prominent converts who continued to observe the Jewish rites after their conversion. But Joseph Judaizers, according to Joseph Perez, were a minority, although relatively important. The same affirms Henry Kamen when he says that "it can be affirmed that in the end of the 1470’s there was no Judaizing movement highlighted or proven among the converts." He also points out that when a convert was accused of judaizing, in many cases the "proofs" that were brought were in fact cultural elements of his Jewish ancestry - such as the Sabbath, not Sunday, as the day of rest - or the lack of knowledge of the new faith - such as not knowing the creed or eating meat in Lent - [29]

This is how the "convergent problem" is born. The baptized can not renounce their faith according to the canonical doctrine of the Church by which Crypto-Judaism is assimilated to heresy, and as such must be punished. This is how they begin to claim various voices including those of some converts who do not want to question the sincerity of their baptism because of those "false" Christians who are beginning to be called Marrano. And it also extends the idea that the presence of the Jews among the Christians is what invites the converts to continue practicing the Law of Moses.[30]

When in 1474 she acceded to the throne, married to the heir of the Crown of Aragon, the future Ferdinand II of Aragon, crypto-Judaism was not punished, "not, of course, by tolerance Or indifference, but because they lacked appropriate legal instruments to characterize this type of crime. "Thus, when they decide to confront the "converso problem", especially after the prior of the Dominicans of Seville, Fray Alonso de Ojeda, in 1475 sent them an alarming report on the number of converts who in that city judaízan, even in an open way,[31] are addressed to Pope Sixtus IV to authorize them to appoint inquisitors in their kingdoms, which the pontiff grants them by the Bull "Exigit sincerae devotionis" of November 1, 1478. "With the creation of the tribunal of the Inquisition, the authorities will have the instrument and the means of in "According to Joseph Perez, Ferdinand and Isabella" were convinced that the Inquisition would compel the converts to integrate definitively: the day when all new Christians renounced Judaism nothing would distinguish them from the other members of the social body."[32]

The expulsion

The segregation of the Jews (1480)

From the beginning of his reign, Isabel and Ferdinand were concerned to protect the Jews - since they were "property" of the crown. For example, on September 6, 1477, in a letter addressed to the Jewish community of Seville, Queen Elizabeth I gave assurances about her safety:[33]

I take under my protection the Jews of the aljamas in general and to each one in particular, as well as to his people and their goods; I protect them against any attack, be it of the nature that is ...; I forbid that they attack, mate or hiera; I also prohibit a passive attitude if attacked, killed or injured.Hence even the Catholic Kings until 1492 were reputed to be favorable to the Jews. This is what the German traveler, Nicolas de Popielovo says, for example, after his visit in 1484-1485:[34] His subjects of Catalonia and Aragon speak publicly and the same things I have heard say to many in Spain that the Queen is protector of the Jews and daughter of a Jewish woman

But the Catholic Monarchs could not do away with all the vexations and discrimination suffered by the Jews, encouraged on many occasions by the preaching of the friars of the mendicant orders. They then made the decision to segregate the Jews to end the conflict. Already in the Cortes of Madrigal of 1476 the kings had protested by the breach of the provisions in the Order of 1412 on the Jews - prohibition to wear luxury dresses; Obligation to wear a red slice on the right shoulder; prohibition to hold positions with authority over Christians, to have Christian servants, to lend money at usurious interest, etc. - but in the Cortes de Toledo of 1480 they decided to go much further to fulfill these norms: to force the Jews to live In separate quarters, from where they could not leave except during the day to carry out their professional occupations. Until then the Jewish quarters-where the Jews used to live and where they had their synagogues, butchers, etc.-had not formed a separate world in the cities and there were also Christians living in them and Jews living outside them. From 1480 onwards, the Jewish quarters were converted into ghettos surrounded by walls and the Jews were confined in them to avoid confusion and damage of our holy faith. A process for which a term of two years was established, but which lasted for more than ten years, and which was not exempt from problems and abuses by Christians.[35]

The text approved by the Cortes, which also included the Mudejar, read as follows:[36]

We send to the aljamas of the said Jews and Moors that each of them who put in said apartment such diligence and give such order as within the said term of the said two years have said houses of their apart, and live and die in them, and henceforth do not have their dwellings among the Christians or elsewhere outside the circuits and places that would be deputies to the said Jewry and die.

The decision of the kings approved by the Courts of Toledo, had antecedents since the Jews already had been confined in some Castilian localities like Cáceres or Soria. In this last locality had been realized with the approval of the kings "to avoid dapnos [sic] that because of bevir and to dwell and to be the Jews among the christianos they followed".[37] Fray Hernando de Talavera, confessor of the queen and who had opposed the use of force to solve the "convergent problem", also justified the segregation "by avoiding many sins, which are followed of the mixture and a great deal of familiarity [between Christians and Jews] and of not keeping everything close to their conversation with Christians by holy canons and civil laws is ordered and commanded."[38]

According to Joseph Perez, with the decision to detain Jews in ghettos, it was not only a question of separating them from Christians and of protecting them, but also of imposing a series of obstacles on them in the development of their activities, so that they would not have more remedy "than to give up their status as Jews if they want to lead a normal existence. Their conversion is not demanded - not yet - nor is their autonomous statute touched, but they proceed with them in such a way that they end up convincing themselves that the only solution is conversion."[39]

The expulsion of the Jews from Andalusia (1483)

The first inquisitors appointed by the kings arrived in Seville in November 1480, "immediately sowing terror". In the first years and only for this city they dictate 700 death sentences and more than five thousand "reconciliations" - that is, prison sentences, exile or simple penances - that are accompanied by the confiscation of their property and the disqualification For public office and ecclesiastical benefits.[40]

In their inquiries the inquisitors discovered that for a long time many converts had met with their Jewish relatives to celebrate Jewish holidays and even attend synagogues.[41] This convinces them that they will not be able to put an end to crypto-Judaism if converts continue to maintain contact with the Jews, for example: what they ask the kings to be expelled from Andalusia. These approve and in 1483 give a period of six months for the Jews of the dioceses of Seville, Cordoba and Cadiz to go to Extremadura. There are doubts as to whether the order was strictly enforced since at the time of the final expulsion in 1492 some chroniclers speak of the fact that eight thousand families of Andalusia embarked in Cadiz and others in Cartagena and in the ports of the Crown of Aragon. On the other hand, the expulsion of the Jews of Saragossa and Teruel was also proposed, but in the end it was not carried out.[42]

According to Julio Valdeón, the decision to expel the Jews from Andalusia also obeyed "the desire to move them away from the border between the crown of Castile and the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, scenario, during the eighties of the fifteenth century And the first years of the 1990s, of the war that ended with the disappearance of the last stronghold of peninsular Islam.[43]

The genesis of the expulsion decree

On March 31, 1492, shortly after the end of the Granada war, the Catholic Kings signed the decree of expulsion of the Jews in Granada, which was sent to all the cities, towns and lordships of their kingdoms with orders strict to not read it or make it public until May 1.[44] It is possible that some prominent Jews tried to nullify or soften it but did not have any success. Among these Jews stands out Isaac Abravanel who offered King Ferdinand a considerable sum of money. According to a well-known legend when the Inquisitor General Tomas de Torquemada found out, he presented himself before the king and threw a crucifix at his feet, saying: "Judas sold our Lord for thirty pieces of silver; His Majesty is about to sell it again for thirty thousand." According to the Israeli historian Benzion Netanyahu, quoted by Julio Valdeón, when Abravanel met with the Queen Isabella said to her, "'Do you think this comes from me? The Lord has put that thought into the heart of the King?"[45]

A few months before a car of faith held in Avila in which three converts and two Jews condemned by the Inquisition were burnt alive for an alleged crime of ritual crime against a Christian child (who will be known as the [Child of the Guard] contributed to create the propitious environment for the expulsion.[46]

The Catholic Kings had precisely entrusted to the [inquisitor general] Tomás de Torquemada and its collaborators the writing of the decree fixing to them, according to the historian Luis Suarez, three previous conditions Which would be reflected in the document: to justify the expulsion by charging Jews with two sufficiently serious offenses - usury and "heretical practice"; That there should be sufficient time for Jews to choose between baptism or exile; And that those who remained faithful to the Mosaic law could dispose of their movable and immovable property, although with the provisos established by the laws-they could not draw either gold, silver, or horses. Torquemada presented the draft decree to the kings on March 20, 1492, and the monarchs signed and published it in Granada on March 31. According to Joseph Perez, that the kings commissioned the drafting of the decree to Torquemada "demonstrates the leading role of [the Inquisition] in that matter."[47]

Of the decree promulgated in Granada on March 31, which was based on the draft decree of Torquemada - drawn up "with the will and consent of their altezas" and which is dated in Santa Fe On March 20 - there are two versions. One signed by the two kings and valid for the Crown of Castile and another signed only by King Ferdinand and valid for the Crown of Aragon. Between the draft decree of Torquemada and the two final versions and between these, they exist, according to Joseph Perez, "significant variants." In contrast to the Torquemada project and the Castilian decree, in the version addressed to the Crown of Aragon the protagonism of the Inquisition is recognized - " Persuading us the venerable father prior of Santa Cruz [Torquemada], inquisitor general of the heretical staidness usury is mentioned as one of the two crimes of which the Jews are accused: "We find the Jewish sayings, by means of great and unbearable usages, to devour and absorb the properties and substances of Christians"; We reaffirm the official position that only the Crown can decide the fate of the Jews since they are the possession of the kings - "they are ours," it is said; And contains more insulting expressions against the Jews: they are accused of making fun of the laws of Christians and of considering them idolaters; Mention is made of the abominable circumstances and of Jewish perfidy. The Judaism of "leprosy" is qualified; It is recalled that the Jews "by their own fault are subject to perpetual servitude, to be slaves and captives."[48]

Regarding the essentials the two versions have the same structure and expose the same ideas. The first part describes the reasons why the kings - or the king in the case of the "Aragonese" version - decide to expel the Jews and in the second part it is detailed how the expulsion is going to take place.[49]

The conditions of expulsion

The second part of the decree detailed the conditions for expulsion:[50]

- The expulsion of the Jews was final: "we agreed to send all Jews and Jews out of our kingdoms and never return or return to them or any of them."

- There was no exception, neither by reason of age, residence or place of birth - include both those born in Castile and Aragon and those from outside.

- There was a period of four months, which would be extended ten more days, until August 10, so that they would leave the kings' domains. Those who did not do so within that period or who returned later would be punished with the death penalty and the confiscation of their property. Likewise, those who aided or concealed the Jews were liable to lose "all their goods, vassals, and fortresses, and other inheritances."

- Within the set period of four months the Jews could sell their real estate and take the proceeds of the sale in the form of bills of exchange, not in coinage or gold and silver because their exit was prohibited by law - or merchandise - as long as they were not arms or horses, whose export was also prohibited.

Although the edict did not refer to a possible conversion, this alternative was implicit. As the historian Luis Suárez pointed out, the Jews had "four months to take the most terrible decision of their lives: to abandon their faith to be integrated in it [in the kingdom, in the political and civil community], or leave the territory in order to preserve it."[51]

The drama that lived the Jews is collected by a contemporary source:[52]

Some Jews, when the term ended, went by night and day as in despair. Many turned from the road ... and received the faith of Christ. Many others, not depriving themselves of the country where they were born and for not selling their goods at that time at fewer prices, were baptized.

The most outstanding Jews, with few exceptions among which the one of Isaac Abravanel stands out, decided to convert to the Christianity. The most relevant case was that of Abraham Senior, the chief rabbi of Castile and one of the closest collaborators of the kings. He and all his relatives were baptized on June 15, 1492 in the Guadalupe monastery, being his godfathers the kings Isabel and Fernando. It took the name of Fernán Núñez Coronel and its son-in-law Mayr Melamed of Fernán Pérez Coronel - the same name of pile that the one of the king. In this case, like that of Abraham de Córdoba, he was given much publicity to serve as an example for the rest of his community. In fact during the four-month tacit term that was given for the conversion many Jews were baptized, especially the rich and the most educated, and among them the vast majority of the rabbis.[53]

A chronicler of the time relates the intense propaganda campaign that unfolded:[54]

In all the synagogues and in the squares and in the churches and in the fields, by the wise men of Spain, and was preached to them by the holy gospel and the doctrine of the holy Mother Church, and was preached and tested by their own Scriptures, how the Messiah who waited were Our Redeemer and Savior Jesus Christ, who came in the time to be agreed, which his ancestors with malice they ignored, and all the others who came after them never wanted to give ear to the truth; before being deceived by the false book of the Talmud, having the truth before their eyes and reading it in their law every day, they ignored it and ignored it.

The Jews who decided not to become "had to prepare themselves for the march in tremendous conditions". They had to sell their goods because they had very little time and had to accept the sometimes ridiculous amounts they offered them in the form of goods that could be carried away because the gold and silver output of the kingdom was prohibited - the possibility of taking bills of exchange were not much help because the bankers, Italians for the most part, demanded them enormous interests. A chronicler of the time attests this:[55]

They sold and squandered everything they could of their estates ... and in everything there were sinister ventures, and the Christians had their estates, very many and very rich houses and inheritances for few monies; and they prayed with them, and found not one to buy them, and gave a house for an ass and a vine for a little cloth or a linen cloth, because they could not bring forth gold or silver.

They also had serious difficulties in recovering the money lent to Christians because either the repayment term was after August 10, deadline for their departure, or many of the debtors denounced "usury fraud", knowing that the Jews, they would not have time for the courts to prove them right.[56] In a letter to the kings, the Ampudia Jews complained that "The mayors of the said village made them and have closed many unreason and grievances says that they do not consent to them, nor do they want them to pay and pay their personal property and that they have no less, but they want to make and pay the debts owed to them and that which they deem urge them to do and then pay them even if the deadlines are not reached."[57]

In addition they had to take care of all the expenses of the trip - transport, maintenance, freight of the ships, tolls, etc. -. This was organized by Isaac Abravanel, who contracted the ships, having to pay very high prices and whose owners in some cases did not fulfill the contract or killed the travelers to steal what little they had. Avranel counted on the collaboration of the real official convert Luis de Santángel and of the banker genovés, Francisco Pinelo.[58]

The kings had to give orders to be protected during the trip, because during the same suffered vexations and abuse. This is how Andrés Bernaldez, pastor of Los Palacios, the time when the Jews had to "abandon their land of their births":[59]

All the young men and daughters who were twelve years old were married to each other, for all the females of this age above were in the shadow and company of husbands... They came out of the lands of their births, children, and children, old and young, on foot and knights on asses and other beasts, and on wagons, and continued their journeys each to the ports that were to go; and went by the roads and fields where they went with many works and fortunes; some falling, others rising, others dying, others being born, others becoming sick, that there was no Christian that there was no pain of them and always because they were invited to baptism and some, with their care, they became and remained but very few, and the rabbis worked them up and made the women and young men sing and play tambourines.

The reasons for the expulsion

In the Castilian version reference is made exclusively to religious motives - in the Aragonese version it is also alluded to usury - because the Jews are accused of "heretical", i.e.: serve as an example and incite the convert to return to the practices of his ancient religion.

At the beginning of the decree It is said that: It is well known that in our domains there are some bad Christians who have Judaized and have committed apostasy against the holy Catholic faith, being the cause most by the relations between Jews and Christians.[62] The following are the measures taken hitherto by kings to end the communication between the Jewish community and the converts, a fundamental cause according to the kings and the Inquisition, that the new Christians, first of all the agreement of the Cortes de Toledo of 1480 by which the Jews were forced to live in neighborhoods separated from the Christians, in order to prevent the Jews from "subverting and subtracting the Christian faithful from our holy Catholic faith." Secondly, the decision to expel the Jews from Andalusia, "believing that this would suffice for those of the other cities and towns and places of our kingdoms and lordships to cease to do and commit the aforesaid." But this measure failed" "because every day it is found and it seems that the said Jews grow in continuing their bad and damaged purpose where they live and talk.'"[63]

Finally, the reason for deciding to expel the entire Jewish community, and not just those of its members who allegedly wanted to "pervert" the Christians, is explained:[64][65]

Because when a serious and detestable crime is committed by a college or university [i.e.: a corporation and a community], it is a reason for such a college or university to be dissolved, and annihilated, and the minors for the elders and the ones for the others punished and that those who pervert the good and honest living of cities and towns and by contagion can harm others to be expelled.

As highlighted Julio Valdeón, "undoubtedly the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian site is one of the most controversial issues of all that have happened throughout the history of Spain." It is not surprising, therefore, that historians have debated whether, in addition to the motives laid out by the Catholic Monarchs in the decree, there were others. Nowadays, some of those who argued at the time, such as the expulsion of the Jews to stay with their wealth, seem to have been discarded, since the majority of the Jews who left were the most modest, while the richest converted and they stayed, and on the other hand, the crown did not benefit at all from the operation - rather it was damaged because it stopped receiving the taxes paid by the Jews. Nor does the argument seem to hold that the expulsion was an episode of classes - the nobility wanted to get rid of an incipient bourgeoisie that represented the Jews and that supposedly threatened their interests - because many Jews were defended by some of the most important nobiliary families of Castile, and because he was also among the ranks of the "bourgeoisie" of "old Christians" where anti-Judaism grew the most.[66][67]

The personal motives of the kings also seem to be ruled out, because everything indicates that they did not feel any repugnance towards Jews and converts. Among the trusted men of the kings were several who belonged to this group, such as the confessor of the queen fray Hernando de Talavera, the steward Andrés Cabrera, the treasurer of the Santa Hermandad Abraham Senior, or as Mayr Melamed or Isaac Abarbanel, without counting the Jewish doctors that attended them.[68]

Current historians prefer to place expulsion in the European context and stand out, such as Luis Suárez Fernández or Julio Valdeón, that the Catholic Kings were in fact the last of the sovereigns of the great western European states to decree The expulsion-the Kingdom of England did it in 1290, the Kingdom of France in 1394; in 1421 the Jews are expelled from Vienna; in 1424 of Linz and of Colonia; in 1439 of Augsburg; in 1442 of Bavaria; in 1485 of Perugia; in 1486 of Vicenza; in 1488 of Parma; in 1489 of Milan and Luca; in 1493 of Sicily; in 1494 of Florence; in 1498 of Provenza...-.[69] The aim of all of them was to achieve unity of faith in their states, a principle that will be defined in the sixteenth century with the formula "cuius regio, eius religio", that the subjects should profess the same religion as their prince.[70]

As Joseph Perez pointed out, the expulsion "puts an end to an original situation in Christian Europe: that of a nation that consents to the presence of different religious communities" with which it "becomes a nation like the rest in Christendom European". "The University of Paris congratulated Spain for having carried out an act of good government, an opinion shared by the best spirits of the time (Machiavelli, Guicciardini, Pico della Mirandola)... [...] it was the so-called medieval coexistence that missed Christian Europe.[71]

Julio Valdeón affirms that the decision of the Catholic Monarchs, who "showed themselves, in their first years of rule, clearly protective of the Hebrews," was due to "pressure from the rest of Christianity" and to "the constant pressure of Church, who often preached against those he called "deicides", as well as the "tremendous animosity that existed in the Christian people against the Jewish community." In this sense he quotes the thesis of the Israeli historian Benzion Netanyahu that the expulsion was the consequence of the climate of racism that was lived in the Christian society of the time.[72] A thesis the latter - that the kings decided the expulsion to ingratiate themselves with the masses in which the anti-Jewish sentiments predominated - that Joseph Perez considers without foundation. "Why should kings have to worry about what the masses felt about Jews and converts when they did not serve the more concrete interests of those masses?" Of the three surviving versions of the expulsion edict, only the third term "usury", which was signed only by Don Fernando, refers to the subject of usury, in very harsh terms, and in the other two versions we do not read a single mention or even the slightest mention of this matter. Accusations that had been repeated for centuries against the Jews: people deicide, desecration of hosts, ritual crimes ... do not appear in any of the three versions."[73]

For Joseph Perez, the decision of the Catholic Monarchs, as evidenced by the content of the Granada Edict, is directly related to the "converso problem". The first step was the creation of the Inquisition, the second the expulsion of the Jews to eliminate those who allegedly incited the converts to Judaize. "What concerned them [the kings] was the total and definitive assimilation of the converts, for which the previous measures failed; they resort to a drastic solution: the expulsion of the Jews to start evil."[74] "The idea of expelling the Jews is part of the Inquisition, of which there is no doubt ... The Inquisition found the expulsion of the Jews the best way to put an end to the Judaizing converts: removed the Catholic Monarchs take the idea to their own account, but this does not mean that the pressure of the inquisitors is low. Heresy is not to their liking, they want to "clean" their kingdom, as the queen wrote, but these concerns are also political: they hope that the elimination of Judaism will facilitate the definitive assimilation and integration of converts into Spanish society".[75]

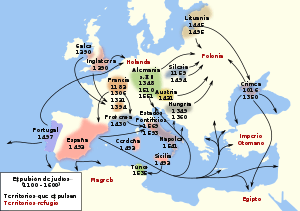

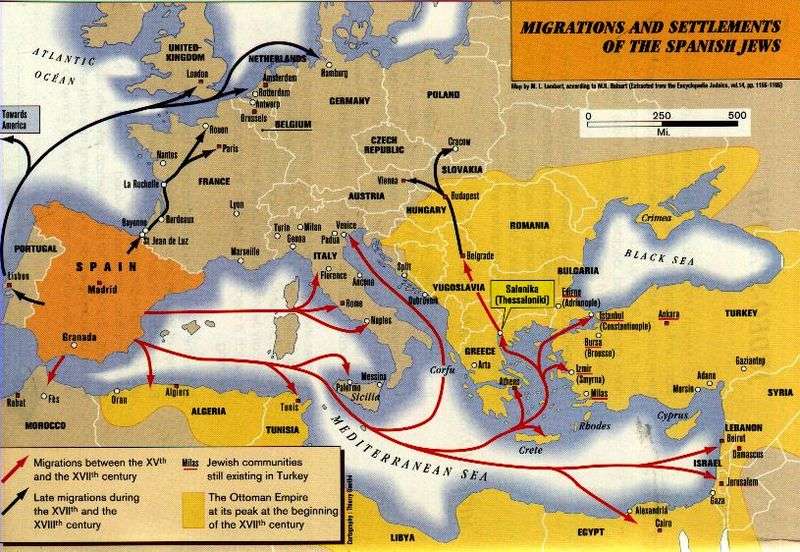

On the other hand, Joseph Perez, following Luis Suárez, places the expulsion within the context of the construction of the "modern state," which requires greater social cohesion based on unity of faith to impose its authority on all groups and individuals of the kingdom. Unlike the medieval period in this type of state, it does not fit the groups that are governed by particular norms, as was the case of the Jewish community. It is therefore not a coincidence, Pérez warns, that only three months after having eliminated the last Muslim stronghold of the peninsula with the conquest of the Nazari kingdom of Granada, they decree the expulsion of the Jews. "What was intended then was to completely assimilate Judaizers and Jews so that there would be no more than Christians. Kings must have thought that the prospect of expulsion would encourage Jews to become massively and that a gradual assimilation would do away with the remnants of Judaism". The vast majority chose to leave, with all that entailed of tears, sacrifices and vexations, and to remain faithful to their faith. "They totally refused to assimilate as an alternative."[76] However, "assimilation" is in this quotation a euphemism: what was offered to the Sephardic was in fact the conversion to a faith that was not his own, hence his Emigration in mass (towards the different directions indicated in the attached map).

Consequences

The end of religious diversity in Spain

As Joseph Perez pointed out, "In 1492 the story of Spanish Judaism ends, which will only lead to an underground existence, always threatened by the Spanish Inquisition and the suspicion of a public opinion that saw In Jews, Judaizers and even sincere converts to natural enemies of Catholicism and Spanish idiosyncrasy, as understood and imposed by some ecclesiastical and intellectual leaders, in an attitude that bordered on racism."[77]

The number of expelled Jews remains controversial. The figures ranged from 45,000 to 350,000, although the most recent investigations, according to Joseph Perez, place it at around 50,000, taking into account the thousands of Jews who left after returning because of the mistreatment they suffered in some places in Fez, Marruecos.[78] Julio Valdeón, citing also the latest investigations, places the figure between 70,000 and 100,000, of which between 50,000 and 80,000 would come from the Crown of Castile, although in these numbers the returnees are not counted.[79]

The situation of those who returned was regularized with an order of November 10, 1492, in which it was established that civil and ecclesiastical authorities had to be witnesses to baptism, and in the event that they had been baptized before returning, evidence and testimonials that confirm it. They were also able to recover all their goods for the same price at which they had sold them. Returns are documented at least until 1499. On the other hand, a provision of the Royal Council of October 24, 1493, determined harsh sanctions for those who reviled these new Christians - calling them "transgressors," for example.[80]

As for the economic impact of the expulsion, it seems to be ruled out that it was a hard setback and stopped the birth of capitalism, which would be one of the causes of the decline of Spain. As Joseph Perez has pointed out, "in view of the published literature on taxation and economic activities, there is no doubt that the Jews were no longer a source of relevant wealth, neither as bankers nor as renters nor as merchants who developed the expulsion of the Jews produced problems at the local level but not a national catastrophe. It is clearly unreasonable to attribute to that event the decadence of Spain and its supposed inability to adapt to the transformations of the modern world. What we now know shows that sixteenth-century Spain was not precisely an economically backward nation. [....] In strictly demographic and economic terms, and apart from human aspects, the expulsion did not imply for Spain any substantial deterioration, but only a temporary crisis Quickly overtaken."[81]

A copy of the Amsterdam Gazette published in the Netherlands on September 12, 1672. The Hebrews of Amsterdam printed a newspaper showing the interest of the Jewish community in what was happening at that time in Madrid and , It also read the news in Spanish - after 180 years of being expelled from its ancestral soil (1492).[82] Document preserved and exhibited in Beth Hatefutsoth, Nahum Goldmann Museum and House of the Diasporas, University of Tel Aviv, State of Israel.

The Sephardic diaspora and the Jewish identity continuity

Most of the expelled Jews settled in North Africa, sometimes via Portugal, or in nearby states, such as the Kingdom of Portugal, the Kingdom of Navarre, or in the Italian states. As of the first two kingdoms also they were expelled to them in 1497 and in 1498 respectively, they had to emigrate again. Those of Navarre settled in Bayona for the most part. And those of Portugal ended up in northern Europe (England or Flanders).

In North Africa, those who went to the Fez kingdom suffered all kinds of ill-treatment and were plundered, even by the Jews who had lived there for a long time. Those who fought the best were those who settled in the territories of the Ottoman Empire, both in North Africa and in the Middle East, as in the Balkans and the Republic of Ragusa, after having passed By Italy. The sultan gave orders to be welcomed and his successor Soliman the Magnificent exclaimed on one occasion referring to King Ferdinand: "You call him king who impoverishes his states to enrich the mine?" This same sultan commented to the ambassador sent by Carlos V who marveled that "they had cast the Jews of Castile, because it was to throw the wealth."[83]

As some Jews identified Spain and the Iberian Peninsula with Biblical Sepharad, the Jews expelled by the Catholic Monarchs took or received the name of Sephardi. These, in addition to their religion, They also kept many of their ancestral customs, and in particular they have preserved the use of the Spanish language, a language which, of course, is not exactly what was spoken in fifteenth-century Spain: like any living language, it evolved and suffered the passage of time, notable alterations, although the structures and essential characteristics remained those of the Castilian late medieval. [...] The Sephardi never forgot the land of their parents, sheltering for her mixed feelings: on the one hand, the resentment for the tragic ones events of 1492, on the other hand, walking the time, the nostalgia of the lost homeland ...".[84]

About judeoespañol as a socio-cultural and identity phenomenon, Garcia-Pelayo and Gross wrote in the twentieth century:

It is said of the Jews expelled from Spain in the s. XV and that preserve in the East the language and the Spanish traditions. The expulsion of the Jews [...] sent a large number of families out of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly from Andalusia and Castile, to settle in the eastern Mediterranean countries dominated by the Turks, where they formed colonies which have survived to this day, especially in Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Turkey, Greece, Bulgaria [...]. These families, generally composed of Sephardic elements of good social standing, have maintained their religion, traditions, language and even their own literature for four and a half centuries. The Spanish that they transported, the one of Castile and Andalusia of ends of century XV, removed from all contact with the one of the Peninsula, has not participated of the evolution undergone by the one of Spain and Spanish colonial America. His phonetics presents some archaic but not degenerate forms; Its vocabulary offers countless Hebrew, Greek, Italian, Arabic, Turkish, according to the countries of residence.[85]

References

- ↑ Suárez Fernández (2012, p. 11)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 98)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, p. 9)

- ↑ Kamen (2011, p. 12)

- ↑ Kamen (2011, pp. 11; 16)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, pp. 10-11)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, pp. 12-13)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, pp. 13-15)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, p. 15)

- ↑ Kamen (2011, p. 17)

- ↑ Perez (2012, pp. 16-17)

- ↑ Kamen (2011, p. 17)

- ↑ Perez (2012, p. 17)

- ↑ Perez (2009, p. 138)

- ↑ Kamen (2011, p. 19)

- ↑ Perez, 2009 & pp. 138; 164-165

- ↑ Pérez (2009, pp. 139-140)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, pp. 165-167)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 168)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 168)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, pp. 168-169)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 174)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, pp. 169-170)

- ↑ Perez (2009, pp. 170-171)

- ↑ Kamen (2011, pp. 17-18)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, pp. 19-20)

- ↑ Kamen (2011, p. 35)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, pp. 20-21)

- ↑ Kamen (2011, pp. 44-46)

- ↑ Perez (2012, pp. 24-25)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, p. 25)

- ↑ Perez (2012, pp. 26-27)

- ↑ Pérez (2012, pp. 21-22)

- ↑ Perez (2009, p. 175)}

- ↑ Pérez (2009, pp. 176-178)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 92)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 92)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 94)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 178)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 181)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, pp. 171-172)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 182)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 93)

- ↑ Rumeu de Armas, Antonio. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, ed. New light on the Santa Fe capitulations of 1492 between the Catholic Monarchs and Christopher Columbus: institutional and diplomatic study. p. 138-141. ISBN 9788400059613.

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 101)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, pp. 185-186)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 187)

- ↑ Perez, 2009 & pp. 187-188

- ↑ Perez (2009, p. 188)

- ↑ Perez (2009, p. 189)

- ↑ Suárez Fernández (2012, p. 415)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 112)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 111)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 112)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 112-113)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 113-114)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 102)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 114)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 114)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 188)

- ↑ Suárez Fernández (2012, p. 414)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 188)

- ↑ Suárez Fernández (2012, p. 414)

- ↑ Suárez Fernández (2012, p. 415)

- ↑ Pérez (2009, p. 188)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, pp. 99-100)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 117-118; 120-)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 124-125)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 8)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, pp. 89; 99)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 136-137)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 101)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 125-126)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 124)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 128-129)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 129-132)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 117)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 102)

- ↑ Valdeón Baruque (2007, p. 102)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 115)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, pp. 118-120)

- ↑ La historia de los judíos en Sefarad (hebreo: España) se remonta a los tiempos de la Antigüedad e involucra a los súbditos del rey Salomón y a otros tantos exiliados del Reino de Judá (Toledo, Sinagoga del Tránsito, La vida judía en Sefarad, noviembre 1991—enero 1992; publicación del Ministerio de Cultura de España, pp. 19-20).

- ↑ Perez (2013)

- ↑ Pérez (2013, p. 117)

- ↑ Ramón García-Pelayo y Gross, Pequeño Larousse Ilustrado, Buenos Aires y México: Larousse, 1977, pp. 603-604.

Bibliography

- Kamen, Henry (2011). Criticism, ed. The Spanish Inquisition. A historical review (3rd ed.). Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-9892-198-4.

- Pérez, Joseph (2009). Marcial Pons, ed. The Jews in Spain. Madrid. ISBN 84-96467 -03-1.

- Brief history of the Inquisition in Spain. Barcelona. 2009. ISBN 978 -84-08-00695-4.

- Perez, Joseph (2013). Criticism, ed. History of a tragedy. The expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-08-05538-9.

- Suárez Fernández, Luis (2012). Ariel, ed. The expulsion of the Jews. A European problem. Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-344-0025-2.

- Editions of The University of Castilla-La Mancha, ed. (2007). "The reign of the Catholic Monarchs. Crucial time of Spanish anti-Judaism". Antimemitism in Spain. Cuenca: Gonzalo Álvarez Chillida and Ricardo Izquierdo Benito. ISBN 978-84-8427-471-1.