Speciation

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

|

History of evolutionary theory |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which biological populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term 'speciation' in 1906 for the splitting of lineages or "cladogenesis", as opposed to "anagenesis" or "phyletic evolution" within lineages.[1][2][3] Charles Darwin was the first to describe the role of natural selection in speciation in his 1859 book The Origin of Species.[4] He also identified sexual selection as a likely mechanism, but found it problematic.

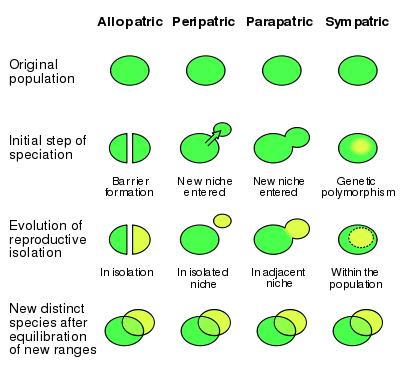

There are four geographic modes of speciation in nature, based on the extent to which speciating populations are isolated from one another: allopatric, peripatric, parapatric, and sympatric. Speciation may also be induced artificially, through animal husbandry, agriculture, or laboratory experiments. Whether genetic drift is a minor or major contributor to speciation is the subject matter of much ongoing discussion.

Modes

All forms of natural speciation have taken place over the course of evolution; however, debate persists as to the relative importance of each mechanism in driving biodiversity.[5]

One example of natural speciation is the diversity of the three-spined stickleback, a marine fish that, after the last glacial period, has undergone speciation into new freshwater colonies in isolated lakes and streams. Over an estimated 10,000 generations, the sticklebacks show structural differences that are greater than those seen between different genera of fish including variations in fins, changes in the number or size of their bony plates, variable jaw structure, and color differences.[6]

Allopatric

During allopatric (from the ancient Greek allos, "other" + Greek patrā, "fatherland") speciation, a population splits into two geographically isolated populations (for example, by habitat fragmentation due to geographical change such as mountain formation). The isolated populations then undergo genotypic or phenotypic divergence as: (a) they become subjected to dissimilar selective pressures; (b) they independently undergo genetic drift; (c) different mutations arise in the two populations. When the populations come back into contact, they have evolved such that they are reproductively isolated and are no longer capable of exchanging genes. Island genetics is the term associated with the tendency of small, isolated genetic pools to produce unusual traits. Examples include insular dwarfism and the radical changes among certain famous island chains, for example on Komodo. The Galápagos Islands are particularly famous for their influence on Charles Darwin. During his five weeks there he heard that Galápagos tortoises could be identified by island, and noticed that finches differed from one island to another, but it was only nine months later that he reflected that such facts could show that species were changeable. When he returned to England, his speculation on evolution deepened after experts informed him that these were separate species, not just varieties, and famously that other differing Galápagos birds were all species of finches. Though the finches were less important for Darwin, more recent research has shown the birds now known as Darwin's finches to be a classic case of adaptive evolutionary radiation.[7]

Peripatric

In peripatric speciation, a subform of allopatric speciation, new species are formed in isolated, smaller peripheral populations that are prevented from exchanging genes with the main population. It is related to the concept of a founder effect, since small populations often undergo bottlenecks. Genetic drift is often proposed to play a significant role in peripatric speciation.

Case Studies:

- Mayr bird fauna[8]

- The Australian bird Petroica multicolor

- Reproductive isolation occurs in populations of Drosophila subject to population bottlenecking

Parapatric

In parapatric speciation, there is only partial separation of the zones of two diverging populations afforded by geography; individuals of each species may come in contact or cross habitats from time to time, but reduced fitness of the heterozygote leads to selection for behaviours or mechanisms that prevent their interbreeding. Parapatric speciation is modelled on continuous variation within a "single," connected habitat acting as a source of natural selection rather than the effects of isolation of habitats produced in peripatric and allopatric speciation.

Parapatric speciation may be associated with differential landscape-dependent selection. Even if there is a gene flow between two populations, strong differential selection may impede assimilation and different species may eventually develop.[9] Habitat differences may be more important in the development of reproductive isolation than the isolation time. Caucasian rock lizards Darevskia rudis, D. valentini and D. portschinskii all hybridize with each other in their hybrid zone; however, hybridization is stronger between D. portschinskii and D. rudis, which separated earlier but live in similar habitats than between D. valentini and two other species, which separated later but live in climatically different habitats.[10]

Ecologists refer to parapatric and peripatric speciation in terms of ecological niches. A niche must be available in order for a new species to be successful. Ring species such as Larus gulls have been claimed to illustrate speciation in progress, though the situation may be more complex.[11] The grass Anthoxanthum odoratum may be starting parapatric speciation in areas of mine contamination.[12]

Sympatric

Sympatric speciation refers to the formation of two or more descendant species from a single ancestral species all occupying the same geographic location.

Often-cited examples of sympatric speciation are found in insects that become dependent on different host plants in the same area.[13][14] However, the existence of sympatric speciation as a mechanism of speciation remains highly debated.[15]

The best illustrated example of sympatric speciation is that of the cichlids of East Africa inhabiting the Rift Valley lakes, particularly Lake Victoria, Lake Malawi and Lake Tanganyika. There are over 800 described species, and according to estimates, there could be well over 1,600 species in the region. Their evolution is cited as an example of both natural and sexual selection.[16][17] A 2008 study suggests that sympatric speciation has occurred in Tennessee cave salamanders.[18] Sympatric speciation driven by ecological factors may also account for the extraordinary diversity of crustaceans living in the depths of Siberia's Lake Baikal.[19]

Budding speciation has been proposed as a particular form of sympatric speciation, whereby small groups of individuals become progressively more isolated from the ancestral stock by breeding preferentially with one another. This type of speciation would be driven by the conjunction of various advantages of inbreeding such as the expression of advantageous recessive phenotypes, reducing the recombination load, and reducing the cost of sex [20]

The hawthorn fly (Rhagoletis pomonella), also known as the apple maggot fly, appears to be undergoing sympatric speciation.[21] Different populations of hawthorn fly feed on different fruits. A distinct population emerged in North America in the 19th century some time after apples, a non-native species, were introduced. This apple-feeding population normally feeds only on apples and not on the historically preferred fruit of hawthorns. The current hawthorn feeding population does not normally feed on apples. Some evidence, such as that six out of thirteen allozyme loci are different, that hawthorn flies mature later in the season and take longer to mature than apple flies; and that there is little evidence of interbreeding (researchers have documented a 4-6% hybridization rate) suggests that sympatric speciation is occurring.[22]

Reinforcement

Reinforcement, also called the Wallace effect, is the process by which natural selection increases reproductive isolation.[23] It may occur after two populations of the same species are separated and then come back into contact. If their reproductive isolation was complete, then they will have already developed into two separate incompatible species. If their reproductive isolation is incomplete, then further mating between the populations will produce hybrids, which may or may not be fertile. If the hybrids are infertile, or fertile but less fit than their ancestors, then there will be further reproductive isolation and speciation has essentially occurred (e.g., as in horses and donkeys.)

The reasoning behind this is that if the parents of the hybrid offspring each have naturally selected traits for their own certain environments, the hybrid offspring will bear traits from both, therefore would not fit either ecological niche as well as either parent. The low fitness of the hybrids would cause selection to favor assortative mating, which would control hybridization. This is sometimes called the Wallace effect after the evolutionary biologist Alfred Russel Wallace who suggested in the late 19th century that it might be an important factor in speciation.[24]

Conversely, if the hybrid offspring are more fit than their ancestors, then the populations will merge back into the same species within the area they are in contact.

Reinforcement favoring reproductive isolation is required for both parapatric and sympatric speciation. Without reinforcement, the geographic area of contact between different forms of the same species, called their "hybrid zone," will not develop into a boundary between the different species. Hybrid zones are regions where diverged populations meet and interbreed. Hybrid offspring are very common in these regions, which are usually created by diverged species coming into secondary contact. Without reinforcement, the two species would have uncontrollable inbreeding. Reinforcement may be induced in artificial selection experiments as described below.

Ecological and parallel speciation

Ecological selection is "the interaction of individuals with their environment during resource acquisition".[25] Natural selection is inherently involved in the process of speciation, whereby, "under ecological speciation, populations in different environments, or populations exploiting different resources, experience contrasting natural selection pressures on the traits that directly or indirectly bring about the evolution of reproductive isolation".[26] Evidence for the role ecology plays in the process of speciation exists. Studies of stickleback populations support ecologically-linked speciation arising as a by-product,[27] alongside numerous studies of parallel speciation.

Parallel speciation is where "greater reproductive isolation repeatedly evolves between independent populations adapting to contrasting environments than between independent populations adapting to similar environments".[28] It is established that ecological speciation occurs and with much of the evidence, "...accumulated from top-down studies of adaptation and reproductive isolation".[28]

Sexual selection

It is widely appreciated that sexual selection could drive speciation in many clades, independently of natural selection.[29] However the term “speciation”, in this context, tends to be used in two different, but not mutually exclusive senses. The first and most commonly used sense refers to the “birth” of new species. That is, the splitting of an existing species into two separate species, or the budding off of a new species from a parent species, both driven by a biological "fashion fad" (a preference for a feature, or features, in one or both sexes, that do not necessarily have any adaptive qualities).[29][30][31][32] In the second sense, "speciation" refers the wide-spread tendency of sexual creatures to be grouped into clearly defined species,[33][34] rather than forming a continuum of phenotypes both in time and space - which would be the more obvious or logical consequence of natural selection. This was indeed recognized by Darwin as problematic, and included in his On the Origin of Species (1859), under the heading "Difficulties with the Theory".[35] There are several suggestions as to how mate choice might play a significant role in resolving Darwin’s dilemma.[34][36][37][38][39][40]

Artificial speciation

New species have been created by domesticated animal husbandry, but the initial dates and methods of the initiation of such species are not clear. Often, the domestic counterpart of the wild ancestor can still interbreed and produce fertile offspring as in the case of domestic cattle, that can be considered the same species as several varieties of wild ox, gaur, yak, etc., or domestic sheep that can interbreed with the mouflon.[41][42]

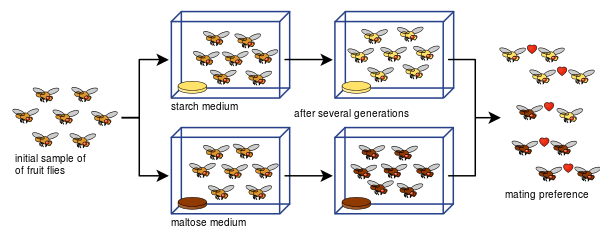

The best-documented creations of new species in the laboratory were performed in the late 1980s. William R. Rice and George W. Salt bred Drosophila melanogaster fruit flies using a maze with three different choices of habitat such as light/dark and wet/dry. Each generation was placed into the maze, and the groups of flies that came out of two of the eight exits were set apart to breed with each other in their respective groups. After thirty-five generations, the two groups and their offspring were isolated reproductively because of their strong habitat preferences: they mated only within the areas they preferred, and so did not mate with flies that preferred the other areas.[43] The history of such attempts is described by Rice and Elen E. Hostert (1993).[44][45] Diane Dodd used a laboratory experiment to show how reproductive isolation can evolve in Drosophila pseudoobscura fruit flies after several generations by placing them in different media, starch- and maltose-based media.[46]

Dodd's experiment has been easy for many others to replicate, including with other kinds of fruit flies and foods.[47] Research in 2005 has shown that this rapid evolution of reproductive isolation may in fact be a relic of infection by Wolbachia bacteria.[48]

Alternatively, these observations are consistent with the notion that sexual creatures are inherently reluctant to mate with individuals whose appearance or behavior is different from the norm. The risk that such deviations are due to heritable maladaptations is very high. Thus, if a sexual creature, unable to predict natural selection's future direction, is conditioned to produce the fittest offspring possible, it will avoid mates with unusual habits or features.[49][50][37][38][39] Sexual creatures will then inevitably tend to group themselves into reproductively isolated species.[38]

Genetics

Few speciation genes have been found. They usually involve the reinforcement process of late stages of speciation. In 2008, a speciation gene causing reproductive isolation was reported.[51] It causes hybrid sterility between related subspecies. The order of speciation of three groups from a common ancestor may be unclear or unknown; a collection of three such species is referred to as a "trichotomy."

Speciation via polyploidization

Polyploidy is a mechanism that has caused many rapid speciation events in sympatry because offspring of, for example, tetraploid x diploid matings often result in triploid sterile progeny.[52] However, not all polyploids are reproductively isolated from their parental plants, and gene flow may still occur for example through triploid hybrid x diploid matings that produce tetraploids, or matings between meiotically unreduced gametes from diploids and gametes from tetraploids (see also hybrid speciation).

It has been suggested that many of the existing plant and most animal species have undergone an event of polyploidization in their evolutionary history.[53][54] Reproduction of successful polyploid species is sometimes asexual, by parthenogenesis or apomixis, as for unknown reasons many asexual organisms are polyploid. Rare instances of polyploid mammals are known, but most often result in prenatal death.

Hybrid speciation

Hybridization between two different species sometimes leads to a distinct phenotype. This phenotype can also be fitter than the parental lineage and as such natural selection may then favor these individuals. Eventually, if reproductive isolation is achieved, it may lead to a separate species. However, reproductive isolation between hybrids and their parents is particularly difficult to achieve and thus hybrid speciation is considered an extremely rare event. The mariana mallard is thought to have arisen from hybrid speciation.

Hybridization is an important means of speciation in plants, since polyploidy (having more than two copies of each chromosome) is tolerated in plants more readily than in animals.[55][56] Polyploidy is important in hybrids as it allows reproduction, with the two different sets of chromosomes each being able to pair with an identical partner during meiosis.[54] Polyploids also have more genetic diversity, which allows them to avoid inbreeding depression in small populations.[57]

Hybridization without change in chromosome number is called homoploid hybrid speciation. It is considered very rare but has been shown in Heliconius butterflies [58] and sunflowers. Polyploid speciation, which involves changes in chromosome number, is a more common phenomenon, especially in plant species.

Gene transposition

Theodosius Dobzhansky, who studied fruit flies in the early days of genetic research in 1930s, speculated that parts of chromosomes that switch from one location to another might cause a species to split into two different species. He mapped out how it might be possible for sections of chromosomes to relocate themselves in a genome. Those mobile sections can cause sterility in inter-species hybrids, which can act as a speciation pressure. In theory, his idea was sound, but scientists long debated whether it actually happened in nature. Eventually a competing theory involving the gradual accumulation of mutations was shown to occur in nature so often that geneticists largely dismissed the moving gene hypothesis.[59]

However, 2006 research shows that jumping of a gene from one chromosome to another can contribute to the birth of new species.[60] This validates the reproductive isolation mechanism, a key component of speciation.[61]

Historical background

In addressing the question of the origin of species, there are two key issues: (1) what are the evolutionary mechanisms of speciation, and (2) what accounts for the separateness and individuality of species in the biota? Since Charles Darwin's time, efforts to understand the nature of species have primarily focused on the first aspect, and it is now widely agreed that the critical factor behind the origin of new species is reproductive isolation.[62] Next we focus on the second aspect of the origin of species.

Darwin's dilemma: Why do species exist?

In On the Origin of Species (1859), Darwin interpreted biological evolution in terms of natural selection, but was perplexed by the clustering of organisms into species.[35] Chapter 6 of Darwin's book is entitled "Difficulties of the Theory." In discussing these "difficulties" he noted "Firstly, why, if species have descended from other species by insensibly fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms? Why is not all nature in confusion instead of the species being, as we see them, well defined?" This dilemma can be referred to as the absence or rarity of transitional varieties in habitat space.[63]

Another dilemma,[64] related to the first one, is the absence or rarity of transitional varieties in time. Darwin pointed out that by the theory of natural selection "innumerable transitional forms must have existed," and wondered "why do we not find them embedded in countless numbers in the crust of the earth." That clearly defined species actually do exist in nature in both space and time implies that some fundamental feature of natural selection operates to generate and maintain species.[35]

The effect of sexual reproduction on species formation

It has been argued that the resolution of Darwin's first dilemma lies in the fact that out-crossing sexual reproduction has an intrinsic cost of rarity.[36][65][66][67][68] The cost of rarity arises as follows. If, on a resource gradient, a large number of separate species evolve, each exquisitely adapted to a very narrow band on that gradient, each species will, of necessity, consist of very few members. Finding a mate under these circumstances may present difficulties when many of the individuals in the neighborhood belong to other species. Under these circumstances, if any species’ population size happens, by chance, to increase (at the expense of one or other of its neighboring species, if the environment is saturated), this will immediately make it easier for its members to find sexual partners. The members of the neighboring species, whose population sizes have decreased, experience greater difficulty in finding mates, and therefore form pairs less frequently than the larger species. This has a snowball effect, with large species growing at the expense of the smaller, rarer species, eventually driving them to extinction. Eventually, only a few species remain, each distinctly different from the other.[36][65][67] The cost of rarity not only involves the costs of failure to find a mate, but also indirect costs such as the cost of communication in seeking out a partner at low population densities.

.jpg)

Rarity brings with it other costs. Rare and unusual features are very seldom advantageous. In most instances, they indicate a (non-silent) mutation, which is almost certain to be deleterious. It therefore behooves sexual creatures to avoid mates sporting rare or unusual features.[37][38] Sexual populations therefore rapidly shed rare or peripheral phenotypic features, thus canalizing the entire external appearance, as illustrated in the accompanying illustration of the African pygmy kingfisher, Ispidina picta. This remarkable uniformity of all the adult members of a sexual species has stimulated the proliferation of field guides on birds, mammals, reptiles, insects, and many other taxa, in which a species can be described with a single illustration (or two, in the case of sexual dimorphism). Once a population has become as homogeneous in appearance as is typical of most species (and is illustrated in the photograph of the African pygmy kingfisher), its members will avoid mating with members of other populations that look different from themselves.[39] Thus, the avoidance of mates displaying rare and unusual phenotypic features inevitably leads to reproductive isolation, one of the hallmarks of speciation.[23][34][70][71]

In the contrasting case of organisms that reproduce asexually, there is no cost of rarity; consequently, there are only benefits to fine-scale adaptation. Thus, asexual organisms very frequently show the continuous variation in form (often in many different directions) that Darwin expected evolution to produce, making their classification into "species" (more correctly, morphospecies) very difficult.[36][37][38][72][73][74]

Rates

There is debate as to the rate at which speciation events occur over geologic time. While some evolutionary biologists claim that speciation events have remained relatively constant and gradual over time (known as "Phyletic gradualism" - see diagram), some palaeontologists such as Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould[75] have argued that species usually remain unchanged over long stretches of time, and that speciation occurs only over relatively brief intervals, a view known as punctuated equilibrium. (See diagram, and Darwin's dilemma.)

Punctuated evolution

Evolution can be extremely rapid, as shown in the creation of domesticated animals and plants in a very short geological space of time, spanning only a few tens of thousands of years. Maize (Zea mays), for instance, was created in Mexico in only a few thousand years, starting about 7,000 to 12,000 years ago.[76] This raises the question of why the long term rate of evolution is far slower than is theoretically possible.[77][78][79][80]

Evolution is imposed on species or groups. It is not planned or striven for in some Lamarckist way.[81] The mutations on which the process depends are random events, and, except for the "silent mutations" which do not affect the functionality or appearance of the carrier, are thus usually disadvantageous, and their chance of proving to be useful in the future is vanishingly small. Therefore, while a species or group might benefit from being able to adapt to a new environment by accumulating a wide range of genetic variation, this is to the detriment of the individuals who have to carry these mutations until a small, unpredictable minority of them ultimately contributes to such an adaptation. Thus, the capability to evolve would require group selection, a concept discredited by (for example) George C. Williams,[82] John Maynard Smith[83] and Richard Dawkins[84][85][86][87] as selectively disadvantageous to the individual.

The resolution to Darwin's second dilemma might thus come about as follows:

If sexual individuals are disadvantaged by passing mutations on to their offspring, they will avoid mutant mates with strange or unusual characteristics.[50][37][38][40] Mutations that affect the external appearance of their carriers will then rarely be passed on to the next and subsequent generations. They would therefore seldom be tested by natural selection. Evolution is, therefore, effectively halted or slowed down considerably. The only mutations that can accumulate in a population, on this punctuated equilibrium view, are ones that have no noticeable effect on the outward appearance and functionality of their bearers (i.e., they are "silent" or "neutral mutations," which can be, and are, used to trace the relatedness and age of populations and species.[37][88]) This argument implies that evolution can only occur if mutant mates cannot be avoided, as a result of a severe scarcity of potential mates. This is most likely to occur in small, isolated communities. These occur most commonly on small islands, in remote valleys, lakes, river systems, or caves,[89] or during the aftermath of a mass extinction.[88] Under these circumstances, not only is the choice of mates severely restricted but population bottlenecks, founder effects, genetic drift and inbreeding cause rapid, random changes in the isolated population's genetic composition.[89] Furthermore, hybridization with a related species trapped in the same isolate might introduce additional genetic changes. If an isolated population such as this survives its genetic upheavals, and subsequently expands into an unoccupied niche, or into a niche in which it has an advantage over its competitors, a new species, or subspecies, will have come in being. In geological terms this will be an abrupt event. A resumption of avoiding mutant mates will thereafter result, once again, in evolutionary stagnation.[75][78]

In apparent confirmation of this punctuated equilibrium view of evolution, the fossil record of an evolutionary progression typically consists of species that suddenly appear, and ultimately disappear, hundreds of thousands or millions of years later, without any change in external appearance.[75][88][90] Graphically, these fossil species are represented by horizontal lines, whose lengths depict how long each of them existed. The horizontality of the lines illustrates the unchanging appearance of each of the fossil species depicted on the graph. During each species' existence new species appear at random intervals, each also lasting many hundreds of thousands of years before disappearing without a change in appearance. The exact relatedness of these concurrent species is generally impossible to determine. This is illustrated in the diagram depicting the distribution of hominin species through time since the hominins separated from the line that led to the evolution of our closest living primate relatives, the chimpanzees.[90]

For similar evolutionary time lines see, for instance, the paleontological list of African dinosaurs, Asian dinosaurs, the Lampriformes and Amiiformes.

See also

References

- ↑ Berlocher 1998, p. 3

- ↑ Cook, Orator F. (March 30, 1906). "Factors of species-formation". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 23 (587): 506–507. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17789700. doi:10.1126/science.23.587.506.

- ↑ Cook, Orator F. (November 1908). "Evolution Without Isolation". The American Naturalist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists. 42 (503): 727–731. ISSN 0003-0147. doi:10.1086/279001.

- ↑ Via, Sara (June 16, 2009). "Natural selection in action during speciation" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 106 (Suppl 1): 9939–9946. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2702801

. PMID 19528641. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901397106.

. PMID 19528641. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901397106. - ↑ Baker, Jason M. (June 2005). "Adaptive speciation: The role of natural selection in mechanisms of geographic and non-geographic speciation". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 36 (2): 303–326. ISSN 1369-8486. PMID 19260194. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2005.03.005.

- ↑ Kingsley, David M. (January 2009). "Diversity Revealed: From Atoms to Traits". Scientific American. Stuttgart: Georg von Holtzbrinck Publishing Group. 300 (1): 52–59. ISSN 0036-8733. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0109-52.

- ↑ Sulloway, Frank J. (September 30, 1982). "The Beagle collections of Darwin's finches (Geospizinae)". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Zoology. London: British Museum (Natural History). 43 (2): 49–58. ISSN 0007-1498.

- ↑ Mayr 1992, pp. 21–53

- ↑ Endler 1977

- ↑ Tarkhnishvili, David; Murtskhvaladze, Marine; Gavashelishvili, Alexander (August 2013). "Speciation in Caucasian lizards: climatic dissimilarity of the habitats is more important than isolation time". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Linnean Society of London. 109 (4): 876–892. ISSN 0024-4074. doi:10.1111/bij.12092.

- ↑ Liebers, Dorit; Knijff, Peter de; Helbig, Andreas J. (2004). "The herring gull complex is not a ring species". Proc Biol Sci. 271 (1542): 893–901. PMC 1691675

. PMID 15255043. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2679.

. PMID 15255043. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2679. - ↑ "Parapatric speciation". University of California Berkeley. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Feder, Jeffrey L.; Xianfa Xie; Rull, Juan; et al. (May 3, 2005). "Mayr, Dobzhansky, and Bush and the complexities of sympatric speciation in Rhagoletis" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 102 (Suppl 1): 6573–6580. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1131876

. PMID 15851672. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502099102.

. PMID 15851672. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502099102. - ↑ Berlocher, Stewart H.; Feder, Jeffrey L. (January 2002). "Sympatric Speciation in Phytophagous Insects: Moving Beyond Controversy?". Annual Review of Entomology. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 47: 773–815. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 11729091. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145312.

- ↑ Daniel I. Bolnick and Benjamin M. Fitzpatrick (2007), "Sympatric Speciation: Models and Empirical Evidence", Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 38: 459–487, doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095804

- ↑ Machado, Heather E.; Pollen, Alexander A.; Hofmann, Hans A.; et al. (December 2009). "Interspecific profiling of gene expression informed by comparative genomic hybridization: A review and a novel approach in African cichlid fishes". Integrative and Comparative Biology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press for the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. 49 (6): 644–659. ISSN 1557-7023. PMID 21665847. doi:10.1093/icb/icp080.

- ↑ Fan, Shaohua; Elmer, Kathryn R.; Meyer, Axel (February 5, 2012). "Genomics of adaptation and speciation in cichlid fishes: recent advances and analyses in African and Neotropical lineages". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. London: Royal Society. 367 (1587): 385–394. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 3233715

. PMID 22201168. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0247.

. PMID 22201168. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0247. - ↑ Niemiller, Matthew L.; Fitzpatrick, Benjamin M.; Miller, Brian T. (May 2008). "Recent divergence with gene flow in Tennessee cave salamanders (Plethodontidae: Gyrinophilus) inferred from gene genealogies". Molecular Ecology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. 17 (9): 2258–2275. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 18410292. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03750.x.

- ↑ Martens, Koen (May 1997). "Speciation in ancient lakes". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 12 (5): 177–182. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01039-2.

- ↑ Joly, E (9 December 2011). "The existence of species rests on a metastable equilibrium between inbreeding and outbreeding. An essay on the close relationship between speciation, inbreeding and recessive mutations.". Biology direct. 6: 62. PMC 3275546

. PMID 22152499. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-62.

. PMID 22152499. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-62. - ↑ Feder, Jeffrey L.; Roethele, Joseph B.; Filchak, Kenneth; et al. (March 2003). "Evidence for inversion polymorphism related to sympatric host race formation in the apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella". Genetics. Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America. 163 (3): 939–953. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1462491

. PMID 12663534. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

. PMID 12663534. Retrieved 2015-09-07. - ↑ Berlocher, Stewart H.; Bush, Guy L. (June 1982). "An electrophoretic analysis of Rhagoletis (Diptera: Tephritidae) phylogeny". Systematic Zoology. Taylor & Francis, Ltd., on behalf of the Society of Systematic Biologists. 31 (2): 136–155. JSTOR 2413033. doi:10.2307/2413033.

- 1 2 Ridley, Mark. "Speciation - What is the role of reinforcement in speciation?". Retrieved 2015-09-07. Adapted from Evolution (2004), 3rd edition (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing), ISBN 978-1-4051-0345-9.

- ↑ Ollerton, Jeff (September 2005). "Speciation: Flowering time and the Wallace Effect" (PDF). Heridity. London: Nature Publishing Group for The Genetics Society. 95 (3): 181–182. ISSN 0018-067X. PMID 16077739. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800718. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ↑ Howard D. Rundle and Patrik Nosil (2005), "Ecological speciation", Ecology Letters, 8: 336–352, doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00715.x

- ↑ Dolph Schluter (2001), "Ecology and the origin of species", Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 16 (7)

- ↑ Jeffrey S. McKinnon; et al. (2004), "Evidence for ecology’s role in speciation", Nature, 429: 294–298, doi:10.1038/nature02556

- 1 2 Dolph Schluter (2009), "Evidence for Ecological Speciation and Its Alternative", Science, 326: 737–740

- 1 2 Panhuis, Tami M.; Butlin, Roger; Zuk, Marlene; et al. (July 2001). "Sexual selection and speciation" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 16 (7): 364–371. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 11403869. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02160-7.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles; A. R. Wallace (1858). "On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection" (PDF). Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. Zoology. 3: 46–50. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1858.tb02500.x.

- ↑ Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species (1st edition). Chapter 4, page 89. http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?viewtype=side&itemID=F373&pageseq=12

- ↑ Eberhard, W. G. (1985). Sexual Selection and Animal Genitalia. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (1980). "A Quahog is a Quahog.". in: The Panda’s thumb. More reflections in natural history. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 204–213. ISBN 0-393-30023-4.

- 1 2 3 Maynard Smith 1989, pp. 275–280

- 1 2 3 Darwin 1859

- 1 2 3 4 Bernstein, Harris; Byerly, Henry C.; Hopf, Frederic A.; et al. (December 21, 1985). "Sex and the emergence of species". Journal of Theoretical Biology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 117 (4): 665–690. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 4094459. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(85)80246-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Koeslag, Johan H. (May 10, 1990). "Koinophilia groups sexual creatures into species, promotes stasis, and stabilizes social behaviour". Journal of Theoretical Biology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 144 (1): 15–35. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 2200930. doi:10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80297-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Koeslag, Johan H. (December 21, 1995). "On the Engine of Speciation". Journal of Theoretical Biology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 177 (4): 401–409. ISSN 0022-5193. doi:10.1006/jtbi.1995.0256.

- 1 2 3 Poelstra, Jelmer W.; Vijay, Nagarjun; Bossu, Christen M.; et al. (June 20, 2014). "The genomic landscape underlying phenotypic integrity in the face of gene flow in crows". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 344 (6190): 1410–1414. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24948738. doi:10.1126/science.1253226.

The Phenotypic Differences between Carrion and Hooded Crows across the Hybridization Zone in Europe are Unlikely to be due to Assortative Mating.

— Commentary by Mazhuvancherry K. Unnikrishnan and H. S. Akhila - 1 2 Miller 2013, pp. 177, 395–396

- ↑ Nowak 1999

- ↑ Hiendleder, Stefan; Kaupe, Bernhard; Wassmuth, Rudolf; et al. (May 7, 2002). "Molecular analysis of wild and domestic sheep questions current nomenclature and provides evidence for domestication from two different subspecies". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. London: Royal Society. 269 (1494): 893–904. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1690972

. PMID 12028771. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1975.

. PMID 12028771. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1975. - ↑ Rice, William R.; Salt, George W. (June 1988). "Speciation Via Disruptive Selection on Habitat Preference: Experimental Evidence". The American Naturalist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists. 131 (6): 911–917. ISSN 0003-0147. doi:10.1086/284831.

- ↑ Rice, William R.; Hostert, Ellen E. (December 1993). "Laboratory Experiments on Speciation: What Have We Learned in 40 Years?". Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons for the Society for the Study of Evolution. 47 (6): 1637–1653. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 2410209. doi:10.2307/2410209.

- ↑ Gavrilets, Sergey (October 2003). "Perspective: Models of Speciation: What Have We Learned in 40 Years?". Evolution. 57 (10): 2197–2215. ISSN 0014-3820. PMID 14628909. doi:10.1554/02-727.

- ↑ Dodd, Diane M. B. (September 1989). "Reproductive Isolation as a Consequence of Adaptive Divergence in Drosophila pseudoobscura". Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons for the Society for the Study of Evolution. 43 (6): 1308–1311. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 2409365. doi:10.2307/2409365.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, Mark; Ravigné, Virginie (March 2002). "Speciation by Natural and Sexual Selection: Models and Experiments". The American Naturalist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists. 159 (S3): S22–S35. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 18707367. doi:10.1086/338370.

- ↑ Koukou, Katerina; Pavlikaki, Haris; Kilias, George; et al. (January 2006). "Influence of Antibiotic Treatment and Wolbachia Curing on Sexual Isolation Among Drosophila melanogaster Cage Populations". Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons for the Society for the Study of Evolution. 60 (1): 87–96. ISSN 0014-3820. PMID 16568634. doi:10.1554/05-374.1.

- ↑ Symons 1979

- 1 2 Langlois, Judith H.; Roggman, Lori A. (March 1990). "Attractive Faces Are Only Average". Psychological Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 1 (2): 115–121. ISSN 0956-7976. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00079.x.

- ↑ Phadnis, Nitin; Orr, H. Allen (January 16, 2009). "A Single Gene Causes Both Male Sterility and Segregation Distortion in Drosophila Hybrids". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 323 (5912): 376–379. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 2628965

. PMID 19074311. doi:10.1126/science.1163934.

. PMID 19074311. doi:10.1126/science.1163934. - ↑ Ramsey, Justin; Schemske, Douglas W. (November 1998). "Pathways, Mechanisms, and Rates of Polyploid Formation in Flowering Plants". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 29: 467–501. ISSN 1545-2069. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.467.

- ↑ Otto, Sarah P.; Whitton, Jeannette (December 2000). "Polyploid Incidence and Evolution". Annual Review of Genetics. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 34: 401–437. ISSN 0066-4197. PMID 11092833. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.401.

- 1 2 Comai, Luca (November 2005). "The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid". Nature Reviews Genetics. London: Nature Publishing Group. 6 (11): 836–846. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 16304599. doi:10.1038/nrg1711.

- ↑ Wendel, Jonathan F. (January 2000). "Genome evolution in polyploids". Plant Molecular Biology. Kluwer Academic Publishers. 42 (1): 225–249. ISSN 0167-4412. PMID 10688139. doi:10.1023/A:1006392424384.

- ↑ Sémon, Marie; Wolfe, Kenneth H. (December 2007). "Consequences of genome duplication". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 17 (6): 505–512. ISSN 0959-437X. PMID 18006297. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2007.09.007.

- ↑ Soltis, Pamela S.; Soltis, Douglas E. (June 20, 2000). "The role of genetic and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 97 (13): 7051–7057. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 34383

. PMID 10860970. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.13.7051.

. PMID 10860970. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.13.7051. - ↑ Mavarez, Jesús; Salazar, Camilo A.; Bermingham, Eldredge; et al. (June 15, 2006). "Speciation by hybridization in Heliconius butterflies". Nature. London: Nature Publishing Group. 441 (7095): 868–871. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16778888. doi:10.1038/nature04738.

- ↑ Sherwood, Jonathan (September 8, 2006). "Genetic Surprise Confirms Neglected 70-Year-Old Evolutionary Theory" (Press release). University of Rochester. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- ↑ Masly, John P.; Jones, Corbin D.; Mohamed, A. F. Noor; et al. (September 8, 2006). "Gene Transposition as a Cause of Hybrid Sterility in Drosophila". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 313 (5792): 1448–1450. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16960009. doi:10.1126/science.1128721.

- ↑ Minkel, J. R. (September 8, 2006). "Wandering Fly Gene Supports New Model of Speciation". Scientific American. Stuttgart: Georg von Holtzbrinck Publishing Group. ISSN 0036-8733. Retrieved 2015-09-11.

- ↑ Mayr 1982, p. 273

- ↑ Sepkoski, David (2012). "1. Darwin's Dilemma: Paleontology, the Fossil Record, and Evolutionary Theory". Rereading the Fossil Record: The Growth of Paleobiology as an Evolutionary Discipline. University of Chicago Press. pp. 9–50. ISBN 978-0-226-74858-0.

One of his greatest anxieties was that the "incompleteness" of the fossil record would be used to criticize his thory: that the apparent "gaps" in fossil succession could be cited as negative evidence, at the very least, for his proposal that all organisms have descended by minute and gradual modifications from a common ancestor.

- ↑ Stower, Hannah (2013). "Resolving Darwin's Dilemma". Nature Reviews Genetics. 14 (747). doi:10.1038/nrg3614.

The near-simultaneous appearance of most modern animal body plans in the Cambrian explosion suggests a brief interval of rapid phenotypic and genetic evolution, which Darwin believed were too fast to be explained by natural selection.

- 1 2 Hopf, Frederic A.; Hopf, F. W. (February 1985). "The role of the Allee effect in species packing". Theoretical Population Biology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 27 (1): 27–50. ISSN 0040-5809. doi:10.1016/0040-5809(85)90014-0.

- ↑ Bernstein & Bernstein 1991

- 1 2 Michod 1995

- ↑ Michod 1999

- ↑ Hockey, Dean & Ryan 2005, pp. 176, 193

- ↑ Mayr 1988

- ↑ Williams 1992, p. 118

- ↑ Maynard Smith, John (December 1983). "The Genetics of Stasis and Punctuation". Annual Review of Genetics. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 17: 11–25. ISSN 0066-4197. PMID 6364957. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.17.120183.000303.

- ↑ Clapham, Tutin & Warburg 1952

- ↑ Grant 1971

- 1 2 3 Gould, Stephen Jay; Eldredge, Niles (Spring 1977). "Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered" (PDF). Paleobiology. Boulder, CO: Paleontological Society. 3 (2): 115–151. ISSN 0094-8373. JSTOR 2400177. doi:10.1017/s0094837300005224. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-24. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- ↑ Laws 2010, pp. 210–215

- ↑ Williams 1992, chpt. 9

- 1 2 Eldredge & Gould 1972, chpt. 5

- ↑ Mayr 1954, pp. 157–180

- ↑ Maynard Smith 1989, p. 281

- ↑ Gould 1980, pt. 4, chpt. 18

- ↑ Williams 1974

- ↑ Maynard Smith, John (March 14, 1964). "Group Selection and Kin Selection". Nature. London: Nature Publishing Group. 201 (4924): 1145–1147. ISSN 0028-0836. doi:10.1038/2011145a0.

- ↑ Dawkins 1995, chpt. 4

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (December 1994). "Burying the Vehicle". Behavioural and Brain Sciences. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 17 (4): 616–617. ISSN 0140-525X. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00036207. Archived from the original on 2006-09-15. Retrieved 2015-09-15. "Remarks on an earlier article by [Elliot] Sober [sic] and David Sloan Wilson, who made a more extended argument in their recent book Unto Others : The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior"

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel C. (December 1994). "E Pluribus Unum?". Behavioural and Brain Sciences. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 17 (4): 617–618. ISSN 0140-525X. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00036219. Archived from the original on 2007-12-27. "Commentary on Wilson & Sober: Group Selection."

- ↑ Pinker, Steven (June 18, 2012). "The False Allure of Group Selection". edge.org. Edge Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- 1 2 3 Campbell 1990, pp. 450–451, 487–490, 499–501

- 1 2 Ayala 1982, pp. 73–83, 182–190, 198–215

- 1 2 McCarthy & Rubidge 2005

Bibliography

- Ayala, Francisco J. (1982). Population and Evolutionary Genetics. Benjamin/Cummings Series in the Life Sciences. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co. ISBN 0-8053-0315-4. LCCN 81021623. OCLC 8034790.

- Berlocher, Stewart H. (1998). "Origins: A Brief History of Research on Speciation". In Howard, Daniel J.; Berlocher, Stewart H. Endless Forms: Species and Speciation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510901-5. LCCN 97031461. OCLC 37545522.

- Bernstein, Carol; Bernstein, Harris (1991). Aging, Sex, and DNA Repair. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-092860-4. LCCN 90014467. OCLC 22542921.

- Campbell, Neil A. (1990). Biology (2nd ed.). Redwood City, CA: Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co. ISBN 0-8053-1800-3. LCCN 89017952. OCLC 20352649.

- Clapham, Arthur Roy; Tutin, Thomas G.; Warburg, Edmund F. (1952). Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. LCCN 52008880. OCLC 1084058.

- Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.). London: John Murray. LCCN 06017473. OCLC 741260650. The book is available from The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- Dawkins, Richard (1995). River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life. Science Masters Series. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-01606-5. LCCN 94037146. OCLC 31376584.

- Eldredge, Niles; Gould, Stephen Jay (1972). "Punctuated Equilibria: An Alternative to Phyletic Gradualism". In Schopf, Thomas J. M. Models in Paleobiology. San Francisco, CA: Freeman Cooper & Co. ISBN 0-87735-325-5. LCCN 72078387. OCLC 572084. Reprinted in Eldredge 1985, pp. 193–223

- Eldredge, Niles (1985). Time Frames: The Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-49555-0. LCCN 84023632. OCLC 11443805.

- Endler, John A. (1977). Geographic Variation, Speciation, and Clines. Monographs in Population Biology. 10. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08187-5. LCCN 76045896. OCLC 2645720.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1980). The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-01380-4. LCCN 80015952. OCLC 6331415.

- Grant, Verne (1971). Plant Speciation. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03208-0. LCCN 75125620. OCLC 139834.

- Hockey, Phil A. R.; Dean, W. Richard J.; Ryan, Peter G., eds. (2005). Roberts Birds of Southern Africa (7th ed.). Cape Town, South Africa: Trustees of the J. Voelcker Bird Book Fund. ISBN 978-0-620-34053-3. LCCN 2006376728. OCLC 65978899.

- Laws, Bill (2010). Fifty Plants that Changed the Course of History. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-798-4. LCCN 2011414731. OCLC 711609823.

- Maynard Smith, John (1989). Evolutionary Genetics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854215-1. LCCN 88017041. OCLC 18069049.

- Mayr, Ernst (1954). "Change of Genetic Environment and Evolution". In Huxley, Julian; Hardy, Alister C.; Ford, Edmund B. Evolution as a Process. London: Allen & Unwin. LCCN 54001781. OCLC 974739.

- Mayr, Ernst (1982). The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-36445-7. LCCN 81013204. OCLC 7875904.

- Mayr, Ernst (1988). Toward a New Philosophy of Biology: Observations of an Evolutionist. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-89665-3. LCCN 87031892. OCLC 17108004.

- Mayr, Ernst (1992). "Speciational Evolution or Punctuated Equilibrium". In Somit, Albert; Peterson, Steven A. Dynamics of Evolution: The Punctuated Equilibrium Debate in the Natural and Social Sciences. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9763-9. LCCN 91055569. OCLC 24374091.

- McCarthy, Terence; Rubidge, Bruce (2005). The Story of Earth & Life: A Southern African Perspective on a 4.6-Billion-Year Journey. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Publishers. ISBN 1-77007-148-2. LCCN 2006376206. OCLC 62098231.

- Michod, Richard E. (1995). Eros and Evolution: A Natural Philosophy of Sex. Helix Books. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-40754-X. LCCN 94013158. OCLC 30625193.

- Michod, Richard E. (1999). Darwinian Dynamics: Evolutionary Transitions in Fitness and Individuality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02699-8. LCCN 98004166. OCLC 38948118.

- Miller, William B., Jr. (2013). The Microcosm Within: Evolution and Extinction in the Hologenome. Boca Raton, FL: Universal-Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61233-277-2. LCCN 2013033832. OCLC 859168474.

- Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9. LCCN 98023686. OCLC 39045218.

- Symons, Donald (1979). The Evolution of Human Sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502535-0. LCCN 78023361. OCLC 4494283.

- Williams, George C. (1974) [Originally published 1966]. Adaptation and Natural Selection: A Critique of Some Current Evolutionary Thought. Princeton Science Library. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02357-3. LCCN 65017164. OCLC 8500898.

- Williams, George C. (1992). Natural Selection: Domains, Levels, and Challenges. Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506933-1. LCCN 91038938. OCLC 228136567.

Further reading

- Coyne, Jerry A.; Orr, H. Allen (2004). Speciation. Sunderlands, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-089-2. LCCN 2004009505. OCLC 55078441.

- Gavrilets, S. (2004), Fitness Landscapes and the Origin of Species, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691119830

- Grant, Verne (1981). Plant Speciation (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-05112-3. LCCN 81006159. OCLC 7552165.

- Marko, Peter B. (2008). "Allopatry". In Jørgensen, Sven Erik; Fath, Brian. Encyclopedia of Ecology. 1, A-C (1st ed.). Oxford, UK: Elsevier. pp. 131–138. ISBN 978-0-444-52033-3. LCCN 2008923435. OCLC 173240026.

- Mayr, Ernst (1963). Animal Species and Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-03750-2. LCCN 63009552. OCLC 899044868.

- Schilthuizen, Menno (2001). Frogs, Flies, and Dandelions: The Making of Species. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850393-8. LCCN 2001270180. OCLC 46729094.

- Shapiro, J. B., Leducq, J-B., Mallet, J. (2016). "What is Speciation?". PLoS Genetics. 12 (3). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005860.

- White, Michael J. D. (1978). Modes of Speciation. A Series of Books in Biology. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-0284-3. LCCN 77010955. OCLC 3203453.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Speciation. |

- Boxhorn, Joseph (September 1, 1995). "Observed Instances of Speciation". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- "Evidence for speciation". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- Hawks, John D. (February 9, 2005). "Speciation". John Hawks Weblog. Retrieved 2015-09-17.

- "Speciation". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-09-17.