Eurypterid

| Eurypterida Temporal range: Darriwilian-Late Permian, 470–252 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eurypterid from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur (1904) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Merostomata |

| Order: | † Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843 |

| Suborders | |

|

† Stylonurina Diener, 1924 | |

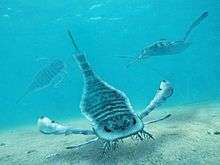

Eurypterids (sea scorpions) are an extinct group of arthropods related to arachnids that include the largest known arthropods to have ever lived. They are members of the extinct order Eurypterida (Chelicerata); which is the most diverse Paleozoic chelicerate order in terms of species.[1] The name Eurypterida comes from the Greek words eury- (meaning "broad" or "wide") and pteron (meaning "wing").[2] This name was chosen due to the pair of wide swimming appendages on the first fossil eurypterids discovered. The largest, such as Jaekelopterus, reached 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) in length, but most species were less than 20 centimetres (8 in). They were formidable predators that thrived in warm shallow water, in both seas and lakes,[3] from the mid Ordovician to late Permian (470 to 248 million years ago).

Although informally called "sea scorpions", only the earliest ones were marine (later ones lived in brackish or freshwater), and they were not true scorpions. According to theory, the move from the sea to fresh water had probably occurred by the Pennsylvanian subperiod. Eurypterids are believed to have undergone ecdysis, making their significance in ecosystems difficult to assess, because it can be difficult to tell a fossil moult from a true fossil carcass.[4] They became extinct during the Permian–Triassic extinction event or sometime before the event 252.17 million years ago. Their fossils have a near global distribution.

About two dozen families of eurypterids are known. Perhaps the best-known genus of eurypterid is Eurypterus, of which around 16 fossil species are known. The genus Eurypterus was described in 1825 by James Ellsworth De Kay, a zoologist. He recognized the arthropod nature of the first-ever described eurypterid specimen, found by Dr. S. L. Mitchill. In 1984, that species, Eurypterus remipes was named the state fossil of New York.

Pentecopterus decorahensis, which lived as early as 467.3 million years ago, is the oldest described eurypterid; with an estimated length of 1.83 metres (6 ft 0 in),[5][6] it has been described as "the first real big predator".[7][8]

Body structure

Eurypterids have been formally described as follows:

Small to very large merostomes with elongate lanceolate, rarely trilobed body; prosoma [head] of moderate size; opisthosoma [body] with 12 moveable segments and styliform to spatulate telson [tail], with division commonly into 7-segmented preabdomen and 5-segmented postabdomen; prosomal [head] appendages 6, comprising 3-jointed chelicerae, walking legs, the last pair commonly transformed into swimming legs. Mouth central, bordered posteriorly by endostoma and metastoma. Operculum with median genital appendage, abdominal appendages plate-shaped with nonlaminate gills. Ordovician-Permian.[9]

The typical eurypterid had a large, flat, semicircular carapace, followed by a jointed section, and finally a tapering, flexible tail, most ending with a long spine at the end (Pterygotus, though, had a large flat tail, possibly with a smaller spine). Behind the head, eurypterids had twelve body segments, each of which was formed from a dorsal plate (tergite) and a ventral plate (sternite). The tail, known as the telson, is spiked in most eurypterids (as in modern scorpions) and in some species it may have been used to inject venom, but there is no evidence that any eurypterids were venomous. Most eurypterids have paddles toward the end of the carapace and beyond, which were used to propel themselves through water. The suborder Stylonurina had walking legs instead of paddles. Some argue that the paddles were also used for digging. Underneath, in addition to the pair of swimming appendages, the creature had four pairs of jointed legs for walking, and two claws at the front, chelicerae, which were enlarged in pterygotids. The walking legs had odd hairs, similar to modern-day crabs. Other features, common to ancient and modern arthropods of this type, include one pair of compound eyes and a pair of smaller eye spots, called ocelli, located between the other, larger, pair of eyes.

Many eurypterids had legs large and long enough to do more than allow them to crawl over the sea bottom; a number of species (particularly hibbertopterids) had large stout legs, and were probably capable of terrestrial locomotion (like terrestrial crabs today). Studies of what are believed to be fossil trackways indicate that eurypterids used in-phase, hexapodous (six-legged) and octopodous (eight-legged) gaits.[10] Some species may have been amphibious, emerging onto land for at least part of their life cycle; they may have been capable of breathing both in water and in air. A predatory arthropod known as Protichnites,[11] whose traces are found in Cambrian strata dating from 510 million years ago, is a possible stem group eurypterid, and is among the first evidence of animals on land.[12]

The largest sea-scorpion and the largest known arthropod ever to have lived is Jaekelopterus rhenaniae, supported by the finding of a 46 cm (18 in) long claw in 2007, indicating a body length of 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in).[13]

Relationships with other groups

Eurypterids have traditionally been regarded as close relatives of horseshoe crabs (Xiphosura), together forming a group called Merostomata.[14] Subsequent studies placed eurypterids closer to the arachnids in a group called Metastomata.[15]

There has also been a prevailing idea that eurypterids are closely related to scorpions, which they resemble.[16] This hypothesis is reflected in the common name "sea scorpion". More recently it has been recognised that a little-known, extinct group called Chasmataspida also shares features with Eurypterida,[17] and the two groups were sometimes confused with one another.

A recent summary of the relationships between arachnids and their relatives recognised Eurypterida, Xiphosura and Arachnida as three major groups, but was not able to resolve the phylogenetic relationship of any shared details between them.[18] Another suggested the eurypterids were sister group to the chasmataspids, with these two groups in turn sister group to the horseshoe crabs.[14]

List of families and genera

There are 246 valid species of eurypterids as of 2011. All of them are extinct. They are grouped into the following:[19]

|

|

Mixopterus, a eurypterid of the Silurian  Eurypterus, the most commonly found eurypterid fossil and the first eurypterid genus to be described  Eurypterus fossil from the Bertie Waterlime (Upper Silurian) of New York.  A fossil of Jaekelopterus rhenaniae. At 2.5 m (8.2 ft) long, it is one of the two largest arthropods to have ever lived (the other being the land-living myriapod Arthropleura). |

The trace fossil trackways produced by eurypterids are placed in the ichnogenus Palmichnium.[20]

Dubious and invalid taxa

|

|

Phylogeny

The cladogram presented here is simplified from a study by Tetlie.[21] The most important phylogenetic breakdown is based on the two major innovations that characterise the evolution of the eurypterids. The most important was the transformation of the posteriormost prosomal appendage into a swimming paddle (as found in the clade Eurypterina). The second innovation was the enlargement of the chelicerae, (as found in the family Pterygotidae), allowing these appendages to be used for active prey capture.

Seventy-five percent of eurypterid species are eurypterines; this represents 99% of specimens.[1] The superfamily Pterygotioidea is the most species-rich clade, with 56 species, followed by the Adelophthalmoidea with 43 species; as sister taxa, they comprise the most derived eurypterids. Pterygotioidea includes the pterygotids, which are the only eurypterids to have a cosmopolitan distribution.[21] This clade is one of the best supported within the eurypterids.

It has been suggested that the development of dermal armour in certain groups of jawless vertebrates (such as the Heterostraci and the Osteostraci) is in response to predation pressure by increasingly sophisticated eurypterid predators[22] (specifically the pterygotids) although this has yet to be verified by detailed analysis.[23] An increase in fish diversity is tied to a decline in eurypterid diversity in the Lower Devonian,[24] although it is not thought that this represents competitive replacement; in fact, this is rare in the fossil record.[25]

| Eurypterida |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Hibbertopterus

- Nepidae—an unrelated insect, commonly known as a "water scorpion"

References

- 1 2 Dunlop, J. A.; D. Penney; O. E. Tetlie; L. I. Anderson (2008). "How many species of fossil arachnids are there?". Journal of Arachnology. 36 (2): 267–272. ISSN 0161-8202. doi:10.1636/CH07-89.1.

- ↑ Webster's New Universal Unabridged Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1979.

- ↑ Joseph T. Hannibal; Spencer G. Lucas; Allan J. Lerner; Dan S. Chaney (2005). S. G. Lucas; K. E. Zeigler; J. A. Spielmann, eds. "The Permian of Central New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 31: 34–38.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Brandt, Danita; McCoy, Victoria (2009). "Scorpion taphonomy: criteria for distinguishing fossil scorpion molts and carcasses". Journal of Arachnology. 37 (3): 312. doi:10.1636/sh09-07.1.

- ↑ Shelton, Jim (August 31, 2015). "Meet Pentecopterus, a new predator from the prehistoric seas". Yale University. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ↑ Staff (September 1, 2015). "Pentecopterus decorahensis: Ancient Giant Sea Scorpion Unearthed in Iowa". Sci-news.com. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ↑ Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (1 September 2015). "The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15: 169. PMC 4556007

. PMID 26324341. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

. PMID 26324341. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. Retrieved 2 September 2015. - ↑ Borenstein, Seth (31 August 2015). "Fossils show big bug ruled the seas 460 million years ago". AP News. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ↑ L. Størmer (1955). "Merostomata". Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part P Arthropoda 2, Chelicerata. p. 23.

- ↑ Whyte, Martin A. (2005). "Palaeoecology: A gigantic fossil arthropod trackway". Nature. 438 (7068): 576–576. PMID 16319874. doi:10.1038/438576a.

- ↑ Richard Owen (1852). "Description of the impressions and footprints of the Protichnites from the Potsdam Sandstone of Canada". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 8: 214–225. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1852.008.01-02.26.

- ↑ Lancaster D. Burling (1917). "Protichnites and Climactichnites. A critical study of some Cambrian trails". American Journal of Science. 44 (263): 387–398. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-44.263.387.

- ↑ Simon J. Braddy; Markus Poschmann; O. Erik Tetlie (2008). "Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod". Biology Letters. 4 (1): 106–109. PMC 2412931

. PMID 18029297. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491.

. PMID 18029297. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491. - 1 2 Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason A. (2014). "Three-dimensional reconstruction and the phylogeny of extinct chelicerate orders". PeerJ. 2: e641. PMC 4232842

. PMID 25405073. doi:10.7717/peerj.641. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

. PMID 25405073. doi:10.7717/peerj.641. Retrieved June 15, 2015. - ↑ P. Weygoldt; H. F. Paulus (1979). "Untersuchungen zur Morphologie, Taxonomie und Phylogenie der Chelicerata". Zeitschrift für zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung. 17 (2): 85–116, 177–200. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1979.tb00694.x.

- ↑ J. Versluys; R. Demoll (1920). "Die Verwandtschaft der Merostomata mit den Arachnida und den anderen Abteilungen der Arthropoda". Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen Amsterdam. 23: 739–765.

- ↑ O. Erik Tetlie; Simon J. Braddy (2004). "The first Silurian chasmataspid, Loganamaraspis dunlopi gen. et sp. nov. (Chelicerata: Chasmataspidida) from Lesmahagow, Scotland, and its implications for eurypterid phylogeny". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. 94 (3): 227–234. doi:10.1017/S0263593300000638.

- ↑ Jeffrey W. Shultz (2007). "A phylogenetic analysis of the arachnid orders based on morphological characters". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 150 (2): 221–265. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.119.850

. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00284.x.

. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00284.x. - ↑ Jason A. Dunlop, David Penney, & Denise Jekel; with additional contributions from Lyall I. Anderson, Simon J. Braddy, James C. Lamsdell, Paul A. Selden, & O. Erik Tetlie (2011). "A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives". In Norman I. Platnick. [http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/index.html The world spider catalog, version 11.5] (PDF). American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved May 21, 2011. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Adolf Seilacher (2007). "Arthropod trackways". Trace Fossil Analysis. Springer. pp. 18–31. ISBN 978-3-540-47225-4.

- 1 2 3 O. Erik Tetlie (2007). "Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (3–4): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011.

- ↑ Romer, A. S. (1933). "Eurypterid influence on vertebrate history". Science. 78 (2015): 114–117. PMID 17749819. doi:10.1126/science.78.2015.114.

- 1 2 O. Erik Tetlie & Derek E. G. Briggs (2009). "The origin of pterygotid eurypterids (Chelicerata: Eurypterida)". Palaeontology. 52 (5): 1141–1148. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00907.x.

- ↑ Briggs, D. E. G.; R. A. Fortey; E. N. K. Clarkson (1988). "Extinction and the fossil record of Arthropods". In G.P. Larwood. Extinction and survival in the fossil record. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Published for the Systematics Association by Clarendon Press. pp. 171–209. ISBN 0198577087.

- ↑ Ridley, Mark (2004). Evolution. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0345-9.

Further reading

- Simon J. Braddy (2001). "Eurypterid Palaeoecology: palaeobiological, ichnological and comparative evidence for a 'mass-moult-mate' hypothesis". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 172 (1–2): 115–132. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00274-7.

- Samuel J. Ciurca (1998). "The Silurian Eurypterid Fauna". Retrieved July 25, 2004.

- John M. Clarke; R. Rudolf (1912). The Eurypterida of New York. Albany, New York: New York State Education Department.

- Neal S. Gupta; O. Erik Tetlie; Derek E. G. Briggs; Richard D. Pancost (2007). "The fossilization of eurypterids: a result of molecular transformation" (PDF). Palaios. 22 (4): 439–447. doi:10.2110/palo.2006.p06-057r.

- Phillip L. Manning; Jason A. Dunlop (1995). "The respiratory organs of eurypterids" (PDF). Palaeontology. 38 (2): 287–297.

- O. Erik Tetlie (2007). "Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (3–4): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011.

- O. Erik Tetlie; Michael B. Cuggy (2007). "Phylogeny of the basal swimming eurypterids (Chelicerata; Eurypterida; Eurypterina)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (3): 345–356. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002131.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eurypterida. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Eurypterids |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Eurypterida |

- Eurypterids.co.uk – eurypterid information website

- Life-like reconstruction of a eurypterid

- Eurypterida from the Palaeos website

- Jaekelopterus rhenaniae at the Palaeoblog