Ulmus laevis

| Ulmus laevis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ulmus laevis, Česká Lípa, Czech Republic | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Ulmaceae |

| Genus: | Ulmus |

| Species: | U. laevis |

| Binomial name | |

| Ulmus laevis Pall. | |

| |

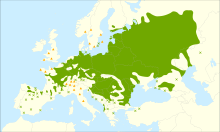

| Distribution map | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ulmus laevis Pall., variously known as the European white elm,[1] fluttering elm, spreading elm, stately elm and, in the USA, the Russian elm, is a large deciduous tree native to Europe, from France[2] northeast to southern Finland, east as far as the Urals, and southeast to Bulgaria and the Crimea; there are also disjunct populations in the Caucasus and Spain, the latter now considered a relict population rather than an introduction by man, and possibly the origin of the European population.[3] U. laevis is rare in the UK, however its random distribution, together with the absence of any record of its introduction, has led at least one British authority to consider it native.[4]

The species was first identified, as Ulmus laevis, by Pallas, in his Flora Rossica published in 1784.[5]

Endemic to alluvial forest, U. laevis is rarely encountered at elevations above 400 m.[6] Most commonly found along rivers such as the Volga and Danube, it is one of very few elms tolerant of prolonged waterlogged, anoxic ground conditions. Although not possessed of an innate genetic resistance to Dutch elm disease, the species is rarely infected in western Europe. The tree is allogamous and is most closely related to the American elm (U. americana).[7]

Description

Ulmus laevis is similar in stature to the wych elm, if rather less symmetric, with a looser branch structure and less neatly rounded crown. It typically reaches a height and breadth of > 30 m, with a trunk < 2 m d.b.h. The extensive shallow root system ultimately forms distinctive high buttresses around the base of the trunk. The bark is smooth at first, then in early maturity breaks into thin grey scales, which separate with age into a network of grey-brown scales and reddish-brown underbark, and finally is deeply fissured in old age like other elms.[8] The leaves are deciduous, alternate, simple ovate with a markedly lop-sided base, < 10 cm long and < 7 cm broad, comparatively thin, often almost papery in texture and very translucent, smooth above with a downy underside. The leaves are shed earlier in autumn than other species of European elm. However, the tree is most reliably distinguished from other European elms by its long flower stems, averaging 20 mm. Moreover, the apetalous wind-pollinated flowers are distinctively cream-coloured,[9] appearing before the leaves in early spring in clusters of 15-30; they are 3–4 mm across. The fruit is a winged samara < 15 mm long by 10 mm broad with a ciliate margin, the single round 5 mm seed maturing in late spring. The seeds have a generally high rate of germination, 45–60% for Serbian trees examined by Stilinović.[10]

Although the species is protandrous, levels of self-pollination can be high[11] The tree can grow very rapidly; where planted in persistently moist soil, trunk width of 13-year-old trees increased by 4 cm per annum at breast height (d.b.h.).[12]

The species is most closely related to the American elm (U. americana), from which it differs mainly in the irregular crown structure and frequent small sprout stems on the trunk and branches, features which also give the tree a distinctive winter silhouette.[13][14] U. americana also has less acute leaf buds, longer petioles, narrower leaves, and a deeper apical notch in the samara which reaches the seed.[15]

Surface root structure exposed by bank erosion

Surface root structure exposed by bank erosion U. laevis buttresses

U. laevis buttresses U. laevis flowers; note long stems

U. laevis flowers; note long stems U. laevis seeds

U. laevis seeds Ulmus laevis leaf

Ulmus laevis leaf U. laevis autumn colour

U. laevis autumn colour Bark of young tree

Bark of young tree Bark in early maturity

Bark in early maturity Bark at maturity (age 100)

Bark at maturity (age 100) Bole of old tree

Bole of old tree%2C_Edinburgh_(1).jpg) Typical epicormic shoots and dense branching

Typical epicormic shoots and dense branching

Pests and diseases

Like other European elms, natural populations of the European white elm have little innate resistance to Dutch elm disease, although research by Irstea has isolated clones able to survive inoculation with the causal fungus, initially losing < 70% of their foliage, but regenerating strongly the following year.[16] Moreover, the tree is not favoured by the vector bark beetles, which colonize it only when there are no other elm alternatives available,[17] an uncommon situation in western Europe. Indeed, in a study of elm in Flanders, not one example of U. laevis was found to be afflicted by Dutch elm disease.[18] Research in Spain[19] has indicated that it is the presence of a triterpene, alnulin, which renders the tree bark unattractive to the beetles. Ergo: the tree's decline in western Europe is chiefly owing to woodland clearance in river valleys, not disease.

It was noted by Jouin at Metz,[13] and a century later by Mittempergher and Santini in Italy, that U. laevis had a very low susceptibility to the elm leaf beetle Xanthogaleruca luteola.[20] Elwes observed that trees planted at Ugbrooke in Devon were infested with Cacopsylla ulmi,[21] which he had never found on any other elm in Britain, an affliction confirmed many years later by Richens, who discovered that the specimens of U. laevis grown at Kew were the only elms in the Gardens afflicted by the louse, and the aphid Tinocallis platani.[22]

The species has a slight to moderate susceptibility to elm yellows.[20]

Cultivation

_080211a.jpg)

U. laevis is essentially a riparian tree, able to withstand over 100 days of continual flooding,[23] although it is intolerant of saline conditions Spanish trees were found to be calcifuge, preferring slightly acid, siliceous soils, and also drought-intolerant, their xylem vessels prone to drought-stress cavitation.[24] However in 2015, a belt of healthy trees approximately 100 years' old were discovered in England planted around a former ammunition dump on the elevated chalk of Salisbury Plain at Hexagon Wood, near Larkhill, about 2 km from Stonehenge.

U. laevis is comparatively weak-wooded, much more so than field elm (Ulmus minor), and thus an inappropriate choice for exposed locations. In trials in southern England by Butterfly Conservation, young trees of <5 m height were badly damaged by wind gusts of 40 knots (75 km/h) in midsummer storms.[12]

The species was never widely introduced to the United States, but is represented at several arboreta. In the Far East, the tree has been planted in Xinjiang province and elsewhere in northern China; planting in Tongliao City is known to have been particularly successful. White elm is also known to have been introduced to Australia.[25]

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the tree has enjoyed a small renaissance in England. A popular larval host plant of the white-letter hairstreak Satyrium w-album butterfly across Europe, the elm is now being planted by Butterfly Conservation and other groups to restore local populations decimated by the effects of Dutch elm disease on native or archaeophytic elms. The Cheshire Wildlife Trust, for example, planted numerous white elms on its reserves in the former Vale Royal district of the county.[12]

Occurrence in the UK

U. laevis is probably not a native of the United Kingdom despite its random occurrence in the countryside, although the date and circumstances of its introduction have not been recorded. The earliest published references to the tree (as U. effusa, citing Willdenow) were in Sibthorp's Flora Oxoniensis (1794),[26] and (as U. effusa Willd. but without description) in Miller's posthumously revised Gardener's and Botanist's Dictionary (1807).[27] The first specimen to be reported in cultivation, in 1838, was at Whiteknights Park, Reading, which featured an elm grove;[28] the tree measured 63 ft (19 m) in height, suggesting it had been planted at the end of the 18th century.[29] However, the authenticity of the Whiteknights tree is a matter of contention; it flowered but did not set fertile seed, which suggested to Loudon that it might be U. campestris (:U. minor 'Atinia'), or, on account of its not throwing up suckers, possibly U. montana (:U. glabra).[29] Moreover, Whiteknights was supplied by the Lee and Kennedy nursery of Hammersmith,[30] which is not known to have stocked U. laevis. The species was not reported from the wild until 1943, with the discovery of a tree in a Surrey hedgerow.[31]

It is possible the tree's distribution was associated with Capability Brown (1716–1783), known to have favoured U. laevis (which he listed among his preferred "native" (sic) trees).[32] This could explain the existence of the seven old specimens discovered by Elwes in 1908 on Mount Pleasant within Ugbrooke Park, Devon,[13] designed by Brown in 1761.[33] Ugbrooke is four miles from Mamhead Park, which had earlier been planted with numerous exotic trees, notably holm oak, collected by its owner, merchant Thomas Ball ( d. 1749) during his commercial travels in Europe.[34][35] Ball's introductions were known to have been marketed by his head gardener William Lucombe, who in 1720 founded the first commercial nursery in the south-west at Exeter.[36] None of Lucombe's early catalogues are known to survive, and thus the introduction of U. laevis through south Devon cannot be confirmed. However, the tree does not feature in any of the surviving arboreta accessions lists, or catalogues of the larger, nationally famous, nurseries of the day, and its earliest-known mention in commerce remains in the south-west, in the catalogue of the Ford & Please nursery (as U. pedunculata) at Exeter circa 1836.[36]

Evidently the tree did not gain in popularity, and was overlooked or ignored by most authors of popular guides to trees in Britain during the 20th century, notably Mabey in his Flora Britannica.[37] The tree is also omitted from Keble-Martin's comprehensive Flora of Devon.[38]

It is not known whether U. laevis was introduced to Scotland before the early 20th century. Two of the three specimens supplied by the Späth nursery, Berlin, to the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh in 1902 as U. effusa may survive in Edinburgh, as it was the practice of the garden to distribute trees about the city;[39] the third specimen was in the garden itself.[40]

Notable trees

The three largest known trees in Europe are at Gülitz in Germany (3.1 m d.b.h.), at Komorów in Poland (2.96 m d.b.h. in 2011), known as the Witcher (tree), and at Bergemolo, 5 km south of Demonte in Piedmont, Italy (bole-girth 6.2 m, 2.0 m d.b.h., height 26 m., 2008).[41][42] Other veterans survive at Casteau, Belgium (bole-girth 5.15 m), in Rahnsdorf near Berlin (bole-girth 4.5 m)[43][44] and in Ritvala, Finland (bole-girth 4.49 m).[45] A lane of Ulmus laevis is found at Eibergen, Netherlands.

Ulmus laevis has very occasionally been planted as an ornamental tree in the UK, and even more randomly in countryside hedgerows. The UK Champion is at Ferry Farm, on the banks of the Tamar at Harewood, Cornwall (27 m high, 1.8 m d.b.h., ).[46] Other examples are few and far between but sometimes of considerable age, surviving amid diseased native elm in Cornwall at Torpoint,[47] and Pencalenick (21 m high, d.b.h. 175 cm),[48] and near Over Wallop in Hampshire (16 m high, 1.3 m d.b.h., 2016) [49] Others can be found in London (Riverside Walk, near Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), Peckham, Tooting, Brighton & Hove, and near St. Albans. In Scotland, examples can be found in Edinburgh (East Fettes Avenue opposite Inverleith Allotments, and North Merchiston Cemetery),[50] while in Wales, two mature trees with numerous suckers occur in a small wood at Rhydyfelin near Aberystwyth.[15][51] On the Channel Islands, the tree is represented by a clump near the well at La Seigneurie (Le Manoir), Sark.[51]

In the United States, a tree of 31.4 m (103 ft) in height (2015) grows at 3331 NE Hancock Street in Portland, Oregon; its age is not known.[52][53]

U. laevis, Casteau, Belgium

U. laevis, Casteau, Belgium Columnar form, Entraygues, France

Columnar form, Entraygues, France Bole of coppiced U. laevis, Over Wallop, UK

Bole of coppiced U. laevis, Over Wallop, UK U. laevis, Ugbrooke, Devon, 1908.

U. laevis, Ugbrooke, Devon, 1908. U. laevis at Syon Park, London, circa 1908.

U. laevis at Syon Park, London, circa 1908. U. laevis, Alfriston, East Sussex, 2006.

U. laevis, Alfriston, East Sussex, 2006.

Uses

The timber of the white elm is of poor quality, the cross-grain causing problems when machined, and thus of little practical use to man, not even as firewood. The density of the timber is significantly lower than that of other European elms. However, owing to its rapid growth, tolerance of soil compaction, air pollution and de-icing salts, the tree has long been used for amenity planting in towns and along roadsides.[7]

Propagation

Usually easy to grow from seed sown to a depth of 6 mm in ordinary compost and kept well-watered. However, as seed viability can vary greatly from year to year, softwood cuttings taken in June may be a more reliable method. The cuttings strike very quickly, well within a fortnight, rapidly producing a dense matrix of roots.

U. laevis seedlings

U. laevis seedlings A rooted cutting of European white elm

A rooted cutting of European white elm

Subspecies and varieties

Several putative varieties have been identified. A variety celtidea from what is now the Ukraine was reported by Rogowicz in the middle of the 19th century, but no examples are known to survive. Another variety parvifolia has been reported from Serbia.[54] 'Simplicidens' is a very rare variety, the only example known to survive is at the National Botanic Garden of Latvia in Salaspils.

Forms

In Russia several ornamental forms are recognized: f. aureovariegata, f. argentovariegata, f. rubra, and f. tiliifolia.

Cultivars

Compared with the other European species of elm, U. laevis has received scant horticultural attention, there being only seven recorded cultivars: Aureovariegata, Colorans, Helena, Ornata, Pendula, Punctata, Urticifolia.

A pyramidal form was reported in 1888 from the Fredericksfelde cemetery in Berlin by Bolle [55] A line of similar monopodial trees can be found (2015) on the island in the Lot at Entraygues, France.

Hybrids

U. laevis does not hybridize naturally, in common with the American elm (U. americana) to which it is closely related. However, in experiments at the Arnold Arboretum, it was successfully crossed with U. thomasii and U. pumila; no such crosses have ever been released to commerce.

Accessions

Europe

- Arboretum de La Petite Loiterie,[56] Monthodon, France. No details available

- Arboretum Freiburg-Günterstal,[57] Germany, no details available

- Brighton & Hove City Council, UK, NCCPG Elm Collection. Ten trees at Hove Recreation Ground, Hove.

- Copenhagen University, Botanic Garden. No details available.

- ELTE Botanic Garden Budapest. Acc. nos. 1998-0718, 1998-0719.

- Grange Farm Arboretum, Sutton St. James, Spalding, Lincolnshire, UK. Acc. no. 502.

- Great Fontley Butterfly Conservation Elm Trials plantation, UK. Two planted 2003, grown from cuttings of specimen at RBG Wakehurst Place, acc. no. 1973-21048.

- Hortus Botanicus Nationalis, Salaspils, Latvia. Acc. nos. 18136, 18140.

- Linnaean Gardens of Uppsala, Sweden. Acc. no. 1930-1014.

- Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, UK. Acc. no. 20070643, from seed wild collected in Val d'Allier, France.

- Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, UK. Acc. nos. 1969-17302, 1973-11712.

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Wakehurst Place, UK. Acc. no. 1973-21048.

- Sir Harold Hillier Gardens, Romsey, Hants. Acc. no. 2016.0385

- Tallinn Botanic Garden, Estonia. No accession details available.

- Thenford House arboretum, Oxfordshire, UK. No details available.

- 'The Leys', University Parks, Oxford, UK. Acc. no. 02678.

- Westonbirt Arboretum,[58] Tetbury, Glos., UK, planted 1997. Acc. no. 1995/322

- Wijdemeren City Council, Netherlands, Elm Collection. Planted 1990 Tjalk, Loosdrecht; 2007 Hinderdam, Nederhorst den Berg; elm lane De Kwakel, Kortenhoef in 2009.

North America

- Arnold Arboretum. Acc. nos. 17910, 637-79, 6951, 753-80.

- Brenton Arboretum, Dallas Center, Iowa. No details available.

- Brooklyn Botanic Garden,[59] New York City. Acc. no. X02589.

- Dominion Arboretum, Canada. No details available

- Longwood Gardens. Acc. nos. 1964-0568, 1964-1119.

- Morton Arboretum, Illinois. Acc. nos. 1302-27, 446-48, 492-64, 27-98.[60]

Nurseries

- Arboretum Waasland, Nieuwkerken-Waas, Belgium[61]

- Boomkwekerij Oirschot, Oirschot, Netherlands[62]

- Dulford Nurseries, Cullompton, Devon, UK[63]

- Lorenz von Ehren, Hamburg, Germany[64]

- Noordplant, Glimmen, Netherlands[65]

- Pan-Global Plants, Frampton-on-Severn, Gloucestershire, UK[66]

- UmbraFlor, Spello, Italy[67]

References

- ↑ "BSBI List 2007". Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 2015-02-25. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ Photographs of U. laevis (L'Orme lisse) in France: in the Forêt du Romersberg, Moselle, (bottom of page), and near Walbourg, Bas-Rhin, (top of page); Archive Krapo arboricole

- ↑ Fuentes-Utrilla, P., Squirrell, J., Hollingsworth, P. M. & Gil, L. (2006). Ulmus laevis (Pallas) in the Iberian Peninsula. An introduced or relict tree species? New data from cpDNA analysis. Genetics Society, Ecological Genetics Group conference, University of Wales Aberystwyth 2006.

- ↑ Medhurst, J. (2013). Archive for the tree detail text Category, p30.

- ↑ Pallas, P. S. (1784). Flora Rossica. i.75, t.48, f.F.

- ↑ Girard, S. (2007). Dossier: L'orme: nouveaux espoirs? Forêt entreprise No. 175, Juillet 2007, Institut pour le developpement forestier, Paris.

- 1 2 Collin, E. (2003). EUFORGEN Technical Guidelines for genetic conservation and use for European white elm (Ulmus laevis). IPGRI, Rome, Italy. ISBN 92-9043-603-4

- ↑ Elwes & Henry (1913), Mitchell (1974), Phillips (1978), Bean (1981).

- ↑ Harris, E. (1996). "The European White Elm in Britain". Quarterly Journal of Forestry. Royal Forestry Society. 90 (2): 122–123.

- ↑ Stilinović, S. (1985): Semenarstvo šumskog i ukrasnog drveća i žbunja. Univerzitet u Beogradu - Šumarski fakultet, Beograd: 1-399/Seed science of forest and decorative trees and bushes, University of Belgrade– Faculty of Forestry, Belgrade: 1-399/

- ↑ Hans, A. S. (1981). Compatibility and Crossability Studies in Ulmus. Silvae Genetica 30, 4–5 (1981).

- 1 2 3 Brookes, A. H. (2015). Disease-resistant elms, Butterfly Conservation trials report, 2015 Butterfly Conservation, Hants & IoW Branch, England.

- 1 2 3 Elwes, Henry John; Henry, Augustine (1913). The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland. 7. pp. 1851–1855. Republished 2004 Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781108069380

- ↑ Bean, W. J. (1981). Trees and shrubs hardy in Great Britain, 7th edition. Murray, London.

- 1 2 Chater, A. O. (1996).'Ulmus laevis naturalized in Cards, VC46'. BSBI News 75 p.63. Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland.

- ↑ Solla et al. (2005). Screening European Elms for Resistance to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. Forest Science, 134–141. 51 (2) 2005. Society of American Foresters.

- ↑ Collin, E., Bilger, I., Eriksson, G., & Turok, J. (2000). The conservation of elm genetic resources in Europe. In Dunn, C. P. (Ed.) (2000). The elms: breeding, conservation & disease management. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston.

- ↑ Vander Mijnsbrugge, K., Vanden Broeck, A., & Van Slycken, J. (2005). A study of Ulmus laevis in Flanders (Northern Belgium). Belgian Journal of Botany, Vol. 138, No. 2 (2005), 199–204. Royal Botanical Society of Belgium.

- ↑ Martín-Benito D., Concepción García-Vallejo M., Alberto Pajares J., López D. 2005. Triterpenes in elms in Spain. Can. J. For. Res. 35: 199–205 (2005).

- 1 2 Mittempergher, L; Santini, A (2004). "The history of elm breeding" (PDF). Investigacion agraria: Sistemas y recursos forestales. 13 (1): 161–177.

- ↑ Jerinić-Prodanović, D. (2006). A new jumping louse, Cacopsylla ulmi Förster (Homoptera, Psyllidae) on elm in Serbia. Acta entomologica serbica. 2006, 11 (1/2): 11–18.

- ↑ Richens, R. H. (1983). Elm. p.64. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521249164

- ↑ Spohn, M. (2008). Trees of Britain & Europe (Black's Nature Guides), 256 p. A & C Black, ISBN 978-140810152-0

- ↑ Venturas, M. et al. (2013). Ulmus laevis Pall. a native elm in the Iberian peninsula: a multidisciplinary approach. Abstracts. 3rd International Elm Conference 2013. The elm after 100 years of Dutch elm disease. Florence 2013. p.48.

- ↑ Spencer, R., Hawker, J. and Lumley, P. (1991). Elms in Australia, Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne, Australia. ISBN 0-7241-9962-4

- ↑ Sibthorp, John (1794). Flora Oxoniensis. p. 87.

- ↑ Miller, P. (1807). The Gardener's and Botanist's Dictionary. Revised by Thomas Martyn, Regius Professor of Botany, University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Hofland, Mrs. (1819). A descriptive account of the mansion and gardens of White-Knights: a seat of His Grace the Duke of Marlborough Private publication, London..

- 1 2 Loudon, John Claudius (1838). Arboretum et fruticetum Britannicum. 3. p. 1397.

- ↑ "White Knights". The gardener's magazine and register of rural & domestic improvement. 9: 665. 1833.

- ↑ Online Atlas of the British & Irish Flora

- ↑ Ignatieva, M. E. and Stewart, G. H. 'Homogeneity of urban biotopes and similarity of landscape design language in former colonial cities', in: McDonnell, M., Hahs, A., & Breuste, J. (eds.) (2009). Ecology of Cities and Towns: A comparative approach. Part III, 23, p. 409. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0521678339

- ↑ Stroud, D. (1950). Capability Brown. New edition 1984, Faber & Faber, London. ISBN 978-0571134052

- ↑ Britton, J. & Brayley, E. W. (1803). Beauties of England & Wales. Vol. 4, Devon & Cornwall, Devonshire, p 99. Various publishers.

- ↑ England, Historic. "UGBROOKE PARK - 1000705- Historic England". HistoricEngland.org.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- 1 2 Harvey, J. (1975). Early Nurserymen. Phillimore, Chichester, UK.

- ↑ Books on trees in Britain in the 20th century: Trimble, L. J. F. (1946) Trees in Britain, Macmillan, London. Step, E. (1904). Wayside And Woodland Trees. A Pocket Guide To The British Sylva. Frederick Warne & Co., London. Gurney, R. (1958). Trees of Britain. Faber & Faber, London. Mabey, R. (1998) Flora Britannica. Chatto & Windus, London. ISBN 978-0701167318

- ↑ Keble-Martin, W., and Fraser, G. (1939). Flora of Devon. Buncle, Arbroath.

- ↑ Accessions book. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. 1902. pp. 45, 47.

- ↑ Tree C2711, RBGE Cultivated herbarium accession book, 1958 Melville annotations

- ↑ Association of Nature Patriarchs in Italy: Piemonte - Olmo di Bergemolo, access-date: November 23, 2016

- ↑ "Google Maps". Google.co.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ Rahnsdorf_Ulme.html

- ↑ "Einzelbäume in Treptow-Köpenick / Land Berlin". Berlin.de. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "European white elm on the estate Oitti in Ritvala". MonumentalTrees.com. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ Harris, E. M. H (1997). "Ulmus laevis - European white-elm" (PDF). BSBI News. Vol. 76. pp. 58–59. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Page not found - Cornwall Council". Cornwall.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ Tree Register of the British Isles.

- ↑ BSBI, (2016). BSBI records for north Hampshire, vc. 12. Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland, Shirehampton, Bristol.

- ↑ U. laevis, East Fettes Avenue , North Merchiston Cemetery

- 1 2 Watsonia (2001). p557

- ↑ "Google Maps". Google.co.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "Ulmus laevis | Heritage Trees by Species | The City of Portland, Oregon". PortlandOregon.gov. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ Jovanović, B. & Radulović, S. (1980). Ulmus laevis var. parvifolia. Glasn. Prir. Muz. u Beogradu. (Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, Belgrade). 35 : 32, 38 (1980). Belgrade, Serbia.

- ↑ Bolle, C. (1888). Ulmus effusa, in Garden & Forest, 32, 381–382, 1888. Garden & Forest Publishing Co. Ltd., USA.

- ↑ "Arboretum de La Petite Loiterie - Un parc pédagogique". Free.fr. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "REIBURG-GÜNTERSTAL ARBORETUM at the Municipal Forest District of Freiburg". Uni-Ulm.de. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ Sorry this page is not available

- ↑ "Brooklyn Botanic Garden". BBG.org. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "Russian Elm - Ulmus laevis". CirrusImage.com. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "English.htm". Arboretum-Waasland.be. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ Plantago - Plantindex

- ↑ Dulford Nurseries - Specialist tree grower

- ↑ "Ulmer Verlag: Bücher & Zeitschriften für Garten, Gartenbau & Landwirtschaft - Ulmer.de". Ulmer.de. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "Home - Noordplant Kwekerijen - Glimmen". Noordplant.nl. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "Pan-global Plants - Specialist plant nursery in Gloucestershire". PanglobalPlants.com. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "UmbraFlor srl - Azienda vivaistica regionale". UmbraFlor.it. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ulmus laevis. |

External links

- Collin, E., 'Ulmus laevis: Technical Guidelines for Genetic Conservation and Use', (2003) European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN)

- Ulmus laevis distribution map: linnaeus.nrm.se

- Ulmus laevis - distribution map, genetic conservation units and related resources. European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN)

- "Herbarium specimen - E00824756". Herbarium Catalogue. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Sheet described as U. effusa Willd.

- "Herbarium specimen - E00824755". Herbarium Catalogue. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Sheet described as U. effusa = U. pedunculata Foug.

- "Herbarium specimen - E00824754". Herbarium Catalogue. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Sheet described as U. laevis Pall.

- "Herbarium specimen - E00824753". Herbarium Catalogue. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Sheet described as U. laevis Pall.