English language in Europe

The English language in Europe, as a native language, is mainly spoken in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Outside of these states, it has a special status in the Crown dependencies (Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey), Gibraltar (one of the British Overseas Territories) and Malta. In the Kingdom of the Netherlands, English has an official status as a regional language on the isles of Saba and Sint Eustatius. In other parts of Europe, English is spoken mainly by those who have learnt it as a second language, but also, to a lesser extent, natively by some expatriates from some countries in the English-speaking world.

The English language is the de facto official language of England, the sole official language of Gibraltar and one of the official languages of the Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Malta, the Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey and the European Union.

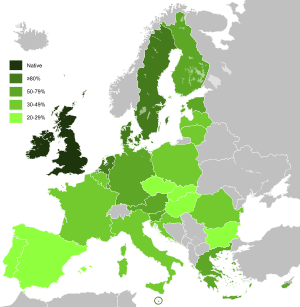

According to a survey published in 2006, 13% of EU citizens speak English as their native language. Another 38% of EU citizens state that they have sufficient skills in English to have a conversation, so the total reach of English in the EU is 51%.[1]

English is descended from the language spoken by the Germanic tribes of the German Bight along the southern coast of the North Sea, the Angles, Saxons, Frisians and Jutes. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, around 449 AD, Vortigern, King of the Britons, issued an invitation to the "Angle kin" (Angles, led by Hengest and Horsa), to help him against the Picts. In return, the Angles were granted lands in the southeast. Further aid was sought, and in response "came men of Ald Seaxum of Anglum of Iotum" (Saxons, Angles and Jutes). The Chronicle documents the subsequent influx of settlers who eventually established seven kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Kent, Essex, Sussex and Wessex.

These Germanic invaders dominated the original Celtic-speaking inhabitants. The dialects spoken by these invaders formed what would be called Old English, which was also strongly influenced by yet another Germanic language, Old East Norse, spoken by Danish Viking invaders who settled mainly in the North-East. English, England and East Anglia are derived from words referring to the Angles: Englisc, Angelcynn and Englaland.

For 300 years following the Norman Conquest in 1066, the Anglo-Norman language was the language of administration and few Kings of England spoke English. A large number of French words were assimilated into Old English, which lost most of its inflections, the result being Middle English. Around the year 1500, the Great Vowel Shift marked the transformation of Middle English into Modern English.

The most famous surviving work from Old English is Beowulf, and from Middle English is Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales.

The rise of Modern English began around the fifteenth century, with Early Modern English reaching its literary pinnacle at the time of William Shakespeare. Some scholars divide early Modern English and late Modern English at around 1800, in concert with British conquest of much of the rest of the world, as the influence of native languages affected English enormously.

Classification and related languages

English belongs to the western sub-branch of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family of languages. The closest undoubted living relatives of English are Scots and the Frisian languages. West Frisian language is spoken by approximately half a million people in the Dutch province of Friesland (Fryslân). Saterland Frisian language is spoken in nearby areas of Germany. North Frisian language is spoken on a few islands in the North Sea. While native English speakers are generally able to read Scots, except for the odd unfamiliar word, Frisian is largely unintelligible (though it was much closer to modern English's predecessors, Middle English and especially Old English).

After Scots and Frisian, the next closest relative is modern Low German of the eastern Netherlands and northern Germany, which was the old homeland of the Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain. Other less closely related living languages include Dutch, Afrikaans, German and the Scandinavian languages. Many French words are also intelligible to an English speaker, as English absorbed a tremendous amount of vocabulary from the Norman language after the Norman conquest and from French in later centuries; as a result, a substantial proportion of English vocabulary is very close to the French, with some slight spelling differences (word endings, use of old French spellings, etc.) and some occasional lapses in meaning.

English in Britain and Ireland

Wales

In 1282 Edward I of England defeated Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Wales's last independent prince, in battle. Edward followed the practice used by his Norman predecessors in their subjugation of the English, and constructed a series of great stone castles in order to control Wales, thus preventing further military action against England by the Welsh. With ‘English’ political control at this time came Anglo-Norman customs and language; English did not displace Welsh as the majority language of the Welsh people until the anti Welsh language campaigns, which began towards the end of the 19th century (54% spoke Welsh in 1891; see Welsh language). The Welsh language is currently spoken by about one-fifth of the population. It has been enjoying support from the authorities for some decades, resulting in a revival, and is in a healthy position in many parts of Wales.

Ireland

The second English dominion was Ireland. With the arrival of the Normans in Ireland in 1169, King Henry II of England gained Irish lands and the fealty of many native Gaelic nobles. By the 14th century, however, English rule was largely limited to the area around Dublin known as the Pale. English influence on the country waned during this period to the point that the English-dominated Parliament was driven to legislate that any Irish of English descent must speak English (requiring those that did not know English to learn it) through the Statutes of Kilkenny in 1367.

English rule expanded in the 16th century by the Tudor conquest of Ireland, leading the Gaelic order to collapse at the start of the 17th century. The Flight of the Earls in 1607 paved the way for the Plantation of Ulster and a deepening of the English language culture in Ireland. The Cromwellian Plantation and suppression of Catholicism, including both native Irish and the "Old English" (those of Anglo-Norman descent), further cemented English influence across the country.

As the centuries passed and the social conditions in Ireland deteriorated, culminating in the Great Irish Famine, Irish parents didn't speak Irish to their children as they knew that the children might have to emigrate and Irish would be of no use outside the home country, in Britain, the United States, Australia or Canada. In addition, the introduction of universal state education in the national schools from 1831 proved a powerful vector for the transmission of English as a home language, with the greatest retreat of the Irish language occurring in the period between 1850 and 1900.

By the 20th century, Ireland had a centuries-old history of diglossia. English was the prestige language while the Irish language was associated with poverty and disfranchisement. Accordingly, some Irish people who spoke both Irish and English refrained from speaking to their children in Irish, or, in extreme cases, feigned the inability to speak Irish themselves. Despite state support for the Irish language in the Irish Free State (later the Republic of Ireland) after independence, Irish continued to retreat, the economic marginality of many Irish-speaking areas (see Gaeltacht) being a primary factor. For this reason Irish is spoken as a mother tongue by only a very small number of people on the island of Ireland. Irish has been a compulsory subject in schools in the Republic since the 1920s and proficiency in Irish was until the mid-1980s required for all government jobs.

It may be noted, however, that certain words (especially those germane to political and civic life) in Irish remain features of Irish life and are rarely, if ever, translated into English. These include the names of legislative bodies (such as Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann), government positions such as Taoiseach and Tánaiste, of the elected representative(s) in the Dáil (Teachta Dála), and political parties (such as Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael). Ireland's police force, the Garda Síochána, are referred to as "the Gardaí", or "the Guards" for short. Irish appears on government forms, euro-currency, and postage stamps, in traditional music and in media promoting folk culture. Irish placenames are still common for houses, streets, villages, and geographic features, especially the thousands of townlands. But with these important exceptions, and despite the presence of Irish loan words in Hiberno-English, Ireland is today largely an English-speaking country. Fluent or native Irish speakers are a minority in the most of the country, with Irish remaining as a vernacular mainly in the relatively small Gaeltacht regions, and most Irish speakers also have fluent English.

Northern Ireland

At the time of partition, English had become the first language of the vast majority in Northern Ireland. It had small elderly Irish-speaking populations in the Sperrin Mountains as well as in the northern Glens of Antrim and Rathlin Island. There were also pockets of Irish speakers in the southernmost part of County Armagh. All of these Irish speakers were bilingual and chose to speak English to their children, and thus these areas of Northern Ireland are now entirely English-speaking. However, in the 2000s a Gaeltacht Quarter was established in Belfast to drive inward investment as a response to a notable level of public interest in learning Irish and the expansion of Irish-medium education (predominantly attended by children whose home language is English) since the 1970s. In recent decades, some Nationalists in Northern Ireland have used it as a means of promoting an Irish identity. However, the amount of interest from Unionists remains low, particularly since the 1960s. About 165,000 people in Northern Ireland have some knowledge of Irish. Ability varies; 64,847 people stated they could understand, speak, read and write Irish in the 2011 UK census, the majority of whom have learnt it as a second language. Otherwise, except for place names and folk music, English is effectively the sole language of Northern Ireland. The Good Friday Agreement specifically acknowledges the position both of Irish and of Ulster Scots in the Republic of Ireland and in Northern Ireland.

Scotland

Anglic speakers were actually established in Lothian by the 7th century, but remained confined there, and indeed contracted slightly to the advance of the Gaelic language. However, during the 12th and 13th centuries, Norman landowners and their retainers, were invited to settle by the king. It is probable that many of their retainers spoke a northern form of Middle English, although probably French was more common. Most of the evidence suggests that English spread into Scotland via the burgh, proto-urban institutions which were first established by King David I. Incoming burghers were mainly English (especially from Northumbria, and the Earldom of Huntingdon), Flemish and French. Although the military aristocracy employed French and Gaelic, these small urban communities appear to have been using English as something more than a lingua franca by the end of the 13th century. English appeared in Scotland for the first time in literary form in the mid-14th century, when its form unsurprisingly differed little from other northern English dialects. As a consequence of the outcome of the Wars of Independence though, the English of Lothian who lived under the King of Scots had to accept Scottish identity. The growth in prestige of English in the 14th century, and the complementary decline of French in Scotland, made English the prestige language of most of eastern Scotland.

Thus, from the end of the 14th century, and certainly by the end of the 15th century, Scotland began to show a split into two cultural areas – the mainly English or Scots Lowlands, and the mainly Gaelic-speaking Highlands (which then could be thought to include Galloway and Carrick; see Galwegian Gaelic). This caused divisions in the country where the Lowlands remained, historically, more influenced by the English to the south: the Lowlands lay more open to attack by invading armies from the south and absorbed English influence through their proximity to and their trading relations with their southern neighbours.

In 1603 the Scottish King James VI inherited the throne of England, and became James I of England. James moved to London and only returned once to Scotland. By the time of James VI's accession to the English throne the old Scottish Court and Parliament spoke Scots. Scots developed from the Anglian spoken in the Northumbrian kingdom of Bernicia, which in the 6th century conquered the Brythonic kingdom of Gododdin and renamed its capital of Din Eidyn to Edinburgh (see the etymology of Edinburgh). Scots continues to heavily influence the spoken English of the Scottish people today. It is much more similar to dialects in the north of England than to 'British' English, even today. The introduction of King James Version of the Bible into Scottish churches also was a blow to the Scots language, since it used Southern English forms.

In 1707 the Scottish and English Parliaments signed a Treaty of Union. Implementing the treaty involved dissolving both the English and the Scottish Parliaments, and transferring all their powers to a new Parliament in London which then became the British Parliament. A customs and currency union also took place. With this, Scotland's position was consolidated within the United Kingdom.

Today, almost all residents of Scotland speak English, although many speak various dialects of Scots which differ markedly from Scottish Standard English. Approximately 2% of the population use Scottish Gaelic as their language of everyday use, primarily in the northern and western regions of the country. Virtually all Scottish Gaelic speakers also speak fluent English.

Isle of Man

The Isle of Man is a Crown Dependency. English and Manx Gaelic are the two official languages. Because so few speak Manx as a first language, all inhabitants of the Isle of Man speak English.

English in other British or formerly British territories

Channel Islands

The bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey are two Crown Dependencies. Besides English, some (very few) inhabitants of these islands speak regional languages, or those related to French (such as Jèrriais, Dgèrnésiais and Sercquiais).

All inhabitants of the Channel Islands speak English.

Gibraltar

Gibraltar has been a British overseas territory since an Anglo-Dutch force led by Sir George Rooke seized "The Rock" in 1704 and Spain ceded the territory in perpetuity to Great Britain in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht.

The small territory's Gibraltarian inhabitants have a rich cultural heritage as a result of the mix of the neighbouring Andalusian population with immigrants from Great Britain, Genoa, Malta, Portugal, Morocco and India.

The vernacular language of the territory is Llanito. It consists of an eclectic mix of Andalusian Spanish and British English as well as languages such as Maltese, Portuguese, Italian of the Genoese variety and Haketia. Even though Andalusian Spanish is the main constituent of Llanito, it is also heavily influenced by British English, involving a certain amount of code-switching into English.

However, English remains the sole official language, used by Government. It is also the medium of instruction in schools and most Gibraltarians who go on to tertiary education do so in the UK. Although Gibraltar receives Spanish television and radio, British television is also widely available via satellite. Whereas a century ago, most Gibraltarians were monolingual Spanish speakers, the majority is now naturally bilingual in English and Spanish.

Cyprus

In 1914 the Ottoman Empire declared war against the United Kingdom and France as part of the complex series of alliances that led to World War I. The British then annexed Cyprus on 2 November 1914 as part of the British Empire, making the Cypriots British subjects. On 5 November 1914 the British and the French declared war on the Ottoman Empire. Most of Cyprus gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1960, with the UK, Greece and Turkey retaining limited rights to intervene in internal affairs. Parts of the island were excluded from the territory of the new independent republic and remain under UK control. These zones are what are known as the Sovereign Base Areas or SBAs.

The British colonial history of Cyprus has left Cypriots with a good level of English but it is no longer an official language in either the Greek south side of the island, formally known as the Republic of Cyprus or the Turkish north, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus though English remains official in the SBAs. Since the effective partition of the island in 1974, Greek and Turkish Cypriots have had little opportunity or inclination to learn the others language, and are more likely to talk to each other in English. Older Turkish Cypriots who worked or lived with Greek Cypriots prior to partition often speak Greek quite fluently. Indeed, many Ottoman soldiers took Greek wives and were allowed to marry up to four.[2]

English is also commonly used on Cyprus to communicate with foreign visitors. The large number of British tourists (and other, largely Northern European ones, who use English as a lingua franca) who visit Cyprus regularly has contributed largely to the continued use of English on Cyprus, especially in its thriving tourist industry.

After independence in the 1960s there was some attempt to encourage French, which was still the most important European language. This policy would have been in line with that in place in Greece at the time. Furthermore, in the 1960s, affluent French-speaking tourists (both from France and Lebanon) in terms of percentage were more important than today. Overall though, the French policy was indicative of a desire to distance Cyprus from the former British colonial power, against which a bitter war of independence had recently been fought and won.

However, knowledge of English is helped by the large Cypriot migrant communities in the UK and Australia, leading to diffusion of culture and language back to their country of origin, and negative sentiments towards the UK have waned or disappeared. There is now a large British expatriate population, in addition to the British military presence in the Sovereign Base Areas, as well as the UN buffer zone, whose peacekeepers usually also use English as a lingua franca. All of the above maintains an English-speaking presence on the island.

Malta

In 1814, Malta became part of the British Empire, under the terms of the Treaty of Vienna. Prior to the arrival of the British, the language of the educated Maltese elite had been Italian, and all legal statutes, taxation, education and clerical discourses were conducted either in Italian or in Latin.

However, this was increasingly downgraded by the increased use of English. The British began scripting and codifying Maltese – hitherto an unscripted vernacular – as a language in or around 1868. From this point on, the Maltese language gradually gained currency as the main language on the islands, its grammars and conventions evolving in a mix between Italian, Arabic and English.

Between the 1870s and 1930s, Malta had three official languages, Italian, Maltese and English, but in 1934, English and Maltese were declared the sole official languages. The British associated Italian with the Benito Mussolini regime in Italy, which had made territorial claims on the islands, although the use of Italian by nationalists was more out of cultural affinities with Italy than any sympathy with Italian Fascism. With the outbreak of World War II, the Maltese lost their sense of fraternity with the Italian world, and there was a decline in Italian spoken in Malta.

English remains an official language in Malta, but since independence in 1964, the country's cultural and commercial links with Italy have strengthened, owing to proximity. Italian television is widely received in Malta and is highly popular.

Other countries

There are also pockets of native English speakers to be found throughout Europe, such as in southern Spain, France, the Algarve in Portugal, as well as numerous U.S. and British military bases in Germany. There are communities of native English speakers in some European cities aside from the cities of the UK and Ireland, e.g., Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, Barcelona, Copenhagen, Paris, Athens, Gothenburg, Helsinki, Stockholm, and Rome.

Sectors of tourism, publishing, finance, computers and related industries rely heavily on English due to Anglophone trade ties. Air traffic control and shipping movements are almost all conducted in English.

In areas of Europe where English is not the first language, there are many examples of the mandated primacy of English: for example, in many European companies, such as Airbus, Ford, G.M., Philips, Renault, Volvo, etc. have designated English to be the language of communication for their senior management, and many universities are offering education in English. The language is also a required subject in most European countries.[3] Thus, the percentage of English speakers is expected to rise.

English as lingua franca

English is the most commonly spoken foreign language in 19 out of 25 European Union countries (excluding the UK and Ireland)[4] In the EU25, working knowledge of English as a foreign language is clearly leading at 38%, followed by German and French (at 14% each), Russian and Spanish (at 6% each), and Italian (3%).[5] "Very good" knowledge of English is particularly high in Malta (52%), Denmark (44%), Cyprus (42%) and Sweden (40%). Working knowledge varies a lot between European countries. It is very high in Malta, Cyprus and Denmark but low in Russia, Spain (12%), Hungary (14%) and Slovakia (14%). On average in 2012, 38% of citizens of the European Union (excluding the United Kingdom and Ireland) stated that they have sufficient knowledge of English to have a conversation in this language.[6]

References

- 1 2 Europeans and their Languages (2006)

- ↑ The Turnstone: A Doctor's Story page 216

- ↑ http://www.euractiv.com/culture/english-dominates-eu-language-cu-news-220783

- ↑ Europeans and their Languages. "Special Eurobarometer 386" of the European Commission (2012), p. 21

- ↑ including native speakers, the figures are: English 38%, German 14%, French 14%, Spanish 6%, Russian 6%, Italian 3%. Europeans and their Languages. "Special Eurobarometer 243" of the European Commission (2006), p. 152

- ↑ Europeans and their Languages. "Special Eurobarometer 386" of the European Commission (2012), p. 24

Countries.png)