Common brown lemur

| Brown Lemur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | Lemuridae |

| Genus: | Eulemur |

| Species: | E. fulvus |

| Binomial name | |

| Eulemur fulvus É. Geoffroy, 1796[3] | |

| |

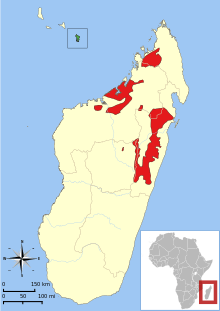

| Distribution of E. fulvus:[1]red = native, green = introduced | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Brown Lemur (Eulemur fulvus), is a species of lemur in the family Lemuridae. It is found in Madagascar and Mayotte.[1]

Range

The common brown lemur lives in western Madagascar north of the Betsiboka River and eastern Madagascar between the Mangoro River and Tsaratanana, as well as in inland Madagascar connecting the eastern and western ranges.[4] They also live on the island of Mayotte, although this population is believed to have been introduced there by man.[4]

Physical description

The common brown lemur has a total length of 84 to 101 centimeters, including 41 to 51 centimeters of tail.[5] Weight ranges from 2 to 3 kilograms.[5] The short, dense fur is primarily brown or grey-brown.[5] The face, muzzle and crown are dark grey or black with paler eyebrow patches, and the eyes are orange-red.[5]

Similar lemur species within their range include the mongoose lemur, E. mongoz, in the west and the red-bellied lemur, E. rubriventer, in the east.[5] They can be distinguished from these species by the fact that E. mongoz is more of a grey color and E. rubriventer is more reddish. There is also some overlap with the black lemur in northeast Madagascar in the Galoko, Manongarivo and Tsaratanana Massifs.[6] There is also overlap and hybridization with the white-fronted brown lemur, E. albifrons, in the northeast portion of the common brown lemur's range.[7]

Diet

The common brown lemur's diet consists primarily of fruits, young leaves, and flowers.[4] In some locations it eats invertebrates, such as cicadas,[5] spiders[5] and millipedes.[8] It also eats bark, sap, soil and red clay (see geophagy).[8] It can tolerate greater levels of toxic compounds from plants than other lemurs can.[4][8]

Behavior

Consistent with its large range, the common brown lemur occupies a variety of forest types, including lowland rainforests, montane rainforests, moist evergreen forests and dry deciduous forests.[5] They spend about 95% of their time in upper layers of the forest and less than 2% of their time on the ground.[8]

They normally live in groups of 5 to 12, but group size can be larger, especially on Mayotte.[5] Groups occupy home ranges of 1 to 9 hectares in the west, but more than 20 hectares in the east.[9] Groups include members of both sexes, including juveniles, and there are no discernible dominance hierarchies.[5]

They are primarily active during the day, but can exhibit cathemeral activity and continue into the night, especially during full moons[5] and during the dry season.[4][10]

In the western part of its range, the common brown lemur overlaps that of the mongoose lemur, and the two species sometimes travel together.[8] In the areas of overlap, the two species also adapt their activity patterns to avoid conflict.[10] For example, the Mongoose Lemur can become primarily nocturnal during the dry season in the areas of overlap.

At Berenty (south Madagascar) there is a population of introduced E. fulvus rufus x collaris.[11] These lemurs show linear hierarchy, adult female dominance, and the presence of conciliatory behavior after aggressions.[12] Additionally, stress levels (measured via self-directed behaviors) decrease at the increase of the hierarchical position of individuals within the social group and reconciliation is able to bring stress down to the baseline levels.[13]

Reproduction

The common brown lemur's mating season is May and June.[5] After a gestation period of about 120 days, the young are born in September and October.[5] Single births are most common, but twins have been reported.[5] The young are weaned after about 4 to 5 months.[5][8] Sexual maturity occurs at about 18 months,[5] and females give birth to their first young at 2 years old.[8] Life span can be as long as 30+ years.[8]

Taxonomy

Five additional currently recognized species of lemur were until 2001 considered subspecies of E. fulvus.[14] These are:

- White-fronted brown lemur, E. albifrons

- Gray-headed lemur, E. cinereiceps

- Collared brown lemur, E. collaris

- Red-fronted brown lemur, E. rufus

- Sanford's brown lemur, E. sanfordi

However, a number of zoologists believe that E. albifrons and E. rufus should continue to be considered subspecies of E. fulvus.[14]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eulemur fulvus. |

- 1 2 3 Andriaholinirina, N.; et al. (2014). "Eulemur fulvus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ "Checklist of CITES Species". CITES. UNEP-WCMC. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Russell Mittermeier; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar (2nd ed.). pp. 272–274. ISBN 1-881173-88-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Nick Garbutt (2007). Mammals of Madagascar. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-0-300-12550-4.

- ↑ Russell Mittermeier; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar (2nd ed.). p. 288. ISBN 1-881173-88-7.

- ↑ Russell Mittermeier; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar (2nd ed.). p. 282. ISBN 1-881173-88-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Noel Rowe (1996). The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. p. 40. ISBN 0-9648825-0-7.

- ↑ name=perspective>Lisa Gould; Michelle Sauther (2007). "Lemuriformes". In Christina J. Campbell; Agustin Fuentes; Katherine C. MacKinnon; Melissa Panger; Simon K. Bearder. Primates in Perspective. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- 1 2 Robert W. Sussman (1999). Primate Ecology and Social Structure Volume 1: Lorises, Lemurs and Tarsiers. pp. 186–187. ISBN 0-536-02256-9.

- ↑ Alison Jolly; Naoki Koyama; Hantanirina Rasamimanana; Helen Crowley; George Williams (2006). "Berenty Reserve: a research site in southern Madagascar". In A. Jolly; R. W. Sussman; N. Koyama; H. Rasamimanana. Ringtailed Lemur Biology: Lemur catta in Madagascar. pp. 32–42. ISBN 0-387-32669-3.

- ↑ Norscia, I.; Palagi, E. (2010). "Do wild brown lemurs reconcile? Not always". Journal of Ethology. doi:10.1007/s10164-010-0228-y.

- ↑ Palagi, E.; Norscia, I. (2010). "Scratching around stress: hierarchy and reconciliation make the difference in wild brown lemurs Eulemur fulvus". Stress. doi:10.3109/10253890.2010.505272.

- 1 2 Russell Mittermeier; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar (2nd ed.). p. 251. ISBN 1-881173-88-7.