Ethnic groups in the United Kingdom

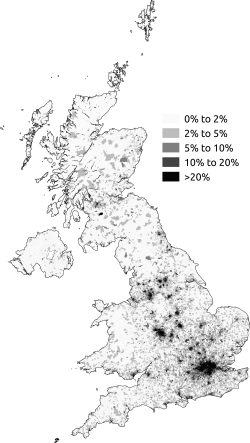

People from various ethnic groups reside in the United Kingdom. Intermittent migration from Northern Europe has been happening for millennia, with other groups such as British Jews also well established. Since World War II, substantial immigration from the New Commonwealth, Europe, and the rest of the world has altered the demography of many cities in the United Kingdom.

History

Historically, British people were believed to be descended from the varied ethnic stocks that settled there before the 11th century; the pre-Celts, Celts, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Norse and the Normans.[1] Some recent genetic analysis has suggested that the majority of the traceable ancestors of the modern British population arrived between 15,000 and 7,500 years ago and that the British broadly share a common ancestry with the Basque people,[2] although there is no consensus amongst geneticists.[3]

The first Jews in Britain were brought to England in 1070 by King William the Conqueror, while Roma in Britain have been documented since the 16th century. The UK has a history of small-scale non-European immigration, with Liverpool having the oldest Black British community, dating back to at least the 1730s during the period of the African slave trade,[4] and the oldest Chinese community in Europe, dating to the arrival of Chinese seamen in the 19th century.[5]

Since 1948 substantial immigration from Africa, the Caribbean and South Asia has been a legacy of ties forged by the British Empire.[6] Migration from new EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe since 2004 has resulted in growth in these population groups.[7]

Sociologist Steven Vertovec argues that whereas "Britain's immigrant and ethnic minority population has conventionally been characterized by large, well-organized African-Caribbean and South Asian communities of citizens originally from Commonwealth countries or formerly colonial territories", more recently the level of diversity of the population has increased significantly, as a result of "an increased number of new, small and scattered, multiple-origin, transnationally connected, socio-economically differentiated and legally stratified immigrants". He terms this "superdiversity".[8]

Official classification of ethnicity

The 2001 UK Census classified ethnicity into several groups: White, Black, Asian, Mixed, Chinese and Other.[10][11] These categories formed the basis for all National Statistics ethnicity statistics until the 2011 Census results were issued.[11] The 1991 UK census was the first to include a question on ethnicity.[12][13] A number of academics have pointed out that the ethnicity classification employed in the census and other official statistics in the UK since 1991 involve confusion between the concepts of ethnicity and race.[14][15] David I. Kertzer and Dominique Arel argue that this is the case in many censuses, and that "the case of Britain is illuminative of the recurring failure to distinguish race from ethnicity".[15] User consultation undertaken for the purpose of planning the 2011 census revealed that some participants thought the "use of colour (White and Black) to define ethnicity is confusing or unacceptable".[16]

Population by ethnicity

According to the 2011 Census, the ethnic composition of the United Kingdom was as set out in the table below.

| Ethnic group | Population (2011) | Percentage of total population[17] |

|---|---|---|

| White or White British: Total | 55,010,359 | 87.1 |

| Gypsy/Traveller/Irish Traveller: Total | 63,193 | 0.1 |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | 1,451,862 | 2.3 |

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | 1,174,983 | 1.9 |

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | 451,529 | 0.7 |

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | 433,150 | 0.7 |

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | 861,815 | 1.4 |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | 4,373,339 | 6.9 |

| Black or Black British: Total[note 1] | 1,904,684 | 3.0 |

| Mixed or Multiple: Total | 1,250,229 | 2.0 |

| Other Ethnic Group: Total | 580,374 | 0.9 |

| Total | 63,182,178 | 100 |

- ↑ For the purpose of harmonising results to make them comparable across the UK, the ONS includes individuals in Scotland who classified themselves in the "African" category (29,638 people), which in the Scottish version of the census is separate from "Caribbean or Black" (6,540 people),[18] in this "Black or Black British" group. The ONS note that "the African categories used in Scotland could potentially capture White/Asian/Other African in addition to Black identities".[19]

Multiculturalism and integration

In 1950 it is estimated there were no more than 20,000 non-white residents in the United Kingdom,mainly in England and almost all born overseas.[20]With considerable migration after the Second World War making the UK an increasingly ethnically and racially diverse state especially in London, race relations policies have been developed that broadly reflect the principles of multiculturalism, although there is no official national commitment to multiculturalism.[21][22][23] This model has faced criticism on the grounds that it has failed to sufficiently promote social integration,[24][25][26] although some commentators have questioned the dichotomy between diversity and integration that this critique presumes.[25] It has been argued that the UK government has since 2001, moved away from policy characterised by multiculturalism and towards the assimilation of minority communities.[27]

Attitudes to multiculturalism

A poll conducted by MORI for the BBC in 2005 found that 62 per cent of respondents agreed that multiculturalism made Britain a better place to live, compared to 32 percent who saw it as a threat.[28] Ipsos MORI data from 2008 by contrast, showed that only 30 per cent saw multiculturalism as making Britain a better place to live, with 38 per cent seeing it as a threat. 41 per cent of respondents to the 2008 poll favoured the development of a shared identity over the celebration of diverse values and cultures, with 27 per cent favouring the latter and 30 per cent undecided.[29]

A study conducted for the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) in 2005 found that in England, the majority of ethnic minority participants called themselves British, whereas indigenous English participants said English first and British second. In Wales and Scotland the majority of white and ethnic minority participants said Welsh or Scottish first and British second, although crucially they saw no incompatibility between the two identities.[30]

Other research conducted for the CRE found that white participants felt that there was a threat to Britishness from large-scale immigration, the claims that they perceived ethnic minorities made on the welfare state, a rise in moral pluralism and perceived political correctness. Much of this frustration was vented at Muslims rather than minorities in general. Muslim participants in the study reported feeling victimised and stated that they felt that they were being asked to choose between Muslim and British identities, whereas they saw it possible to be both.[31]

See also

- British people

- Demography of the United Kingdom

- Foreign-born population of the United Kingdom

- Historical immigration to Great Britain

- Immigration to the United Kingdom since 1922

- Languages of the United Kingdom

- Prehistoric settlement of the British Isles

References

- ↑ Duffy, Jonathan (20 April 2001). "Are the British a race?". BBC News. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Stephen (21 October 2006). "Myths of British ancestry". Prospect. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (6 March 2007). "A United Kingdom? Maybe". New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ Costello, Ray (2001). Black Liverpool: The Early History of Britain's Oldest Black Community 1730–1918. Liverpool: Picton Press. ISBN 1-873245-07-6.

- ↑ "Culture and Ethnicity Differences in Liverpool – Chinese Community". Chambré Hardman Trust. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ↑ "Short History of Immigration". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Vargas-Silva, Carlos (10 April 2014). "Migration Flows of A8 and other EU Migrants to and from the UK". Migration Observatory, University of Oxford. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Vertovec, Steven (2007). "Super-diversity and its implications". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 30 (6): 1024–1054. doi:10.1080/01419870701599465.

- ↑ "Harmonised Concepts and Questions for Social Data Sources - Primary Standards: Ethnic Group" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ "Presenting ethnic and national groups data". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- 1 2 "How do you define ethnicity?". Office for National Statistics. 4 November 2003. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ↑ "How has ethnic diversity grown 1991-2001-2011?" (PDF). ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity. December 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Sillitoe, K.; White, P. H. (1992). "Ethnic Group and the British Census: The Search for a Question". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society). 155 (1): 141–163. JSTOR 2982673.

- ↑ Ballard, Roger (1996). "Negotiating race and ethnicity: Exploring the implications of the 1991 census". Patterns of Prejudice. 30 (3): 3–33. doi:10.1080/0031322X.1996.9970192.

- 1 2 Kertzer, David I.; Arel, Dominique (2002). "Censuses, identity formation, and the struggle for political power". In Kertzer, David I.; Arel, Dominique. Census and Identity: The Politics of Race, Ethnicity, and Language in National Censuses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–42.

- ↑ "Final recommended questions for the 2011 Census in England and Wales: Ethnic group" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. October 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ "2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom". Office for National Statistics. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ↑ "Table KS201SC - Ethnic group: All people" (PDF). National Records of Scotland. 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "Ethnic group". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ Haug, Werner; Compton, Paul; Courbage, Youssef (2002). The Demographic Characteristics of Immigrant Populations. Council of Europe. ISBN 9789287149749.

- ↑ Favell, Adrian (1998). Philosophies of Integration: Immigration and the Idea of Citizenship in France and Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-17609-0.

- ↑ Kymlicka, Will (2007). Multicultural Odysseys: Navigating the New International Politics of Diversity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 0-19-928040-1.

- ↑ Panayi, Panikos (2004). "The evolution of multiculturalism in Britain and Germany: An historical survey". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 25 (5/6): 466–480. doi:10.1080/01434630408668919.

- ↑ "Race chief wants integration push". BBC News. 3 April 2004. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- 1 2 "So what exactly is multiculturalism?". BBC News. 5 April 2004. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ "Davis attacks UK multiculturalism". BBC News. 3 August 2005. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ "Race, Faith, and UK Policy: a brief history", University of York, archived from the original on June 5, 2011, retrieved October 27, 2016

- ↑ "UK majority back multiculturalism". BBC News. 10 August 2005. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ "Doubting multiculturalism" (PDF). Trend Briefing 1. Ipsos MORI. May 2009. p. 3. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ ETHNOS Research and Consultancy (November 2005). "Citizenship and belonging: What is Britishness?" (PDF). Commission for Racial Equality. p. 37. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ ETHNOS Research and Consultancy (May 2006). "The decline of Britishness: A research study" (PDF). Commission for Racial Equality. p. 4. Retrieved 24 October 2010.