Poles

The Poles (Polish: Polacy, pronounced [pɔˈlat͡sɨ]; singular masculine: Polak, singular feminine: Polka) are a nation and West Slavic ethnic group native to Poland who share a common ancestry, culture, history and are native speakers of the Polish language. The population of Poles in Poland is estimated at 37,394,000 out of an overall population of 38,538,000 (based on the 2011 census).[1] Poland's population inhabits several historic regions, including Greater Poland, Lesser Poland, Mazovia, Silesia, Pomerania, Kuyavia, Warmia (Ermland), Masuria, and Podlachia.

Over a thousand years ago, the Polans – an influential tribe in Greater Poland region, inhabiting the areas around Giecz, Gniezno, and Poznań – succeeded in uniting various Lechitic tribes under what became the Piast dynasty,[36] thereby creating the Polish state.

A wide-ranging Polish diaspora (the Polonia) exists throughout Europe (Germany, France, Belarus, the United Kingdom, Russia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Ireland, Scandinavia, Italy, Belgium, Spain), the Americas (the United States, Brazil, Canada, Argentina) and in Australasia (Australia and New Zealand). Today the largest urban concentration of Poles is the Katowice urban agglomeration (the Silesian Metropolis) of 2.7 million inhabitants.

Polish émigrés have included individuals with important roles in American society, such as Generals Casimir Pulaski, Tadeusz Kosciuszko and Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski (a first cousin to composer Frédéric Chopin), and National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski. Poland was also for centuries a refuge for many Jews from all over Europe; a large number emigrated in the twentieth century to Israel. Several prominent Israeli statesmen were born in Poland, including Israel's founder David Ben-Gurion, former President of Israel Shimon Peres, and Prime Ministers Yitzhak Shamir and Menachem Begin.

Origins

Slavs have been in the territory of modern Poland for over 1500 years. They organized into tribal units, of which the larger ones were later known as the Polish tribes; the names of many tribes are found on the list compiled by the anonymous Bavarian Geographer in the 9th century.[37] In the 9th and 10th centuries the tribes gave rise to developed regions along the upper Vistula (the Vistulans within the Great Moravian Empire sphere),[37] the Baltic Sea coast and in Greater Poland. The last tribal undertaking resulted in the 10th century in a lasting political structure and state, Poland, one of the West Slavic nations.[38]

The concept which has become known as the Piast Idea, the chief proponent of which was Jan Ludwik Popławski, is based on the statement that the Piast homeland was inhabited by so-called "native" aboriginal Slavs and Slavonic Poles since time immemorial and only later was "infiltrated" by "alien" Celts, Germans, Turkic peoples and others. After 1945 the so-called "autochthonous" or "aboriginal" school of Polish prehistory received official backing in Poland and a considerable degree of popular support. According to this view, the Lusatian Culture which archaeologists have identified between the Oder and the Vistula in the early Iron Age, is said to be Slavonic; all non-Slavonic tribes and peoples recorded in the area at various points in ancient times are dismissed as "migrants" and "visitors". In contrast, the critics of this theory, such as Marija Gimbutas, regard it as an unproved hypothesis and for them the date and origin of the westward migration of the Slavs is largely uncharted; the Slavonic connections of the Lusatian Culture are entirely imaginary; and the presence of an ethnically mixed and constantly changing collection of peoples on the Middle European Plain is taken for granted.[39]

Statistics

Polish people are the sixth largest national group in the European Union.[40] Estimates vary depending on source, though available data suggest a total number of around 60 million people worldwide (with roughly 21 million living outside of Poland, many of whom are not of Polish ethnicity, but Polish nationals).[7] There are almost 38 million Poles in Poland alone. There are also Polish minorities in the surrounding countries including Germany, and indigenous minorities in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, northern and eastern Lithuania, western Ukraine, and western Belarus. There are some smaller indigenous minorities in nearby countries such as Moldova. There is also a Polish minority in Russia which includes indigenous Poles as well as those forcibly deported during and after World War II; the total number of Poles in what was the former Soviet Union is estimated at up to 3 million.[41]

The term "Polonia" is usually used in Poland to refer to people of Polish origin who live outside Polish borders, officially estimated at around 10 to 20 million. There is a notable Polish diaspora in the United States, Brazil, and Canada. France has a historic relationship with Poland and has a relatively large Polish-descendant population. Poles have lived in France since the 18th century. In the early 20th century, over a million Polish people settled in France, mostly during world wars, among them Polish émigrés fleeing either Nazi occupation or later Soviet rule.

In the United States, a significant number of Polish immigrants settled in Chicago, Ohio, Detroit, New Jersey, New York City, Orlando, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and New England. The highest concentration of Polish Americans in a single New England municipality is in New Britain, Connecticut. The majority of Polish Canadians have arrived in Canada since World War II. The number of Polish immigrants increased between 1945 and 1970, and again after the end of Communism in Poland in 1989. In Brazil the majority of Polish immigrants settled in Paraná State. Smaller, but significant numbers settled in the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Espírito Santo and São Paulo (state). The city of Curitiba has the second largest Polish diaspora in the world (after Chicago) and Polish music, dishes and culture are quite common in the region.

A recent large migration of Poles took place following Poland's accession to the European Union and opening of the EU's labor market; with an approximate number of 2 million, primarily young, Poles taking up jobs abroad.[42] It is estimated that over half a million Polish people have come to work in the United Kingdom from Poland. Since 2011, Poles have been able to work freely throughout the EU and not just in the United Kingdom, Ireland and Sweden where they have had full working rights since Poland's EU accession in 2004. The Polish community in Norway has increased substantially and has grown to a total number of 120,000, making Poles the largest immigrant group in Norway.

Culture

The culture of Poland has a history of 1000 years.[43] Poland, located in Central Europe, developed a character that was influenced by its geography at the confluence of fellow Central European cultures (Austrian, Czech, German, Hungarian, and Slovak) as well as from Western European cultures (French, Spanish and Dutch), Southern European cultures (Italian and Greek), Baltic/Northeastern cultures (Lithuanian, Estonian and Latvian), Eastern European cultures (Belarusian and Ukrainian) and Western Asian/Caucasian cultures (Ottoman Turkish, Armenian, and Georgian). Influences were also conveyed by immigrants (Hungarian, Sloval, Czech, Jewish, German and Dutch), political alliances (with Lithuania, Hungary, Saxony, France and Sweden), conquests of the Polish-Lithuanian state (Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Romania and Latvia) and conquerors of the Polish lands (the Russian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia and the Habsburg monarchy, later to be known as the Austrian Empire or Austria-Hungary).

Over time, Polish culture has been greatly influenced by its ties with the Germanic, Latinate and other ethnic groups and minorities living in Poland.[44] The people of Poland have traditionally been seen as hospitable to artists from abroad (especially Italy) and open to cultural and artistic trends popular in other European countries. Owing to this central location, the Poles came very early into contact with both civilizations – eastern and western, and as a result developed economically, culturally, and politically. A German general Helmut Carl von Moltke, in his Poland. A historical sketch (1885), stated that "Poland of the fifteenth century was one of the most civilised states of Europe."

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Polish focus on cultural advancement often took precedence over political and economic activity, experiencing severe crises, especially during World War II and in the following years. These factors have contributed to the versatile nature of Polish art, with all its complex nuances.[44]

Language

The Polish language (Polish: język polski) is a West Slavic language and the official language of Poland. Its written form uses the Polish alphabet, which is the Latin alphabet with the addition of a few diacritic marks.

Poland is the most linguistically homogeneous European country; nearly 97% of Poland's citizens declare Polish as their mother tongue. Elsewhere, ethnic Poles constitute large minorities in Germany, northern Slovakia and the Czech Republic, Hungary, northeast Lithuania and western Belarus and Ukraine. Polish is the most widely used minority language in Lithuania's Vilnius County (26% of the population, according to the 2001 census results) and is found elsewhere in northeastern and western Lithuania. In Ukraine it is most common in the western Lviv and Volyn oblast (provinces), while in western Belarus it is used by the significant Polish minority, especially in the Brest and Grodno regions and in areas along the Lithuanian border.

The geographical distribution of the Polish language was greatly affected by the border changes and population transfers that followed World War II. Poles resettled in the "Recovered Territories" in the west and north. Some Poles remained in the previously Polish-ruled territories in the east that were annexed by the USSR, resulting in the present-day Polish-speaking minorities in Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine, although many Poles were expelled or emigrated from those areas to areas within Poland's new borders. Meanwhile, the flight and expulsion of Germans, as well as the expulsion of Ukrainians and resettlement of Ukrainians within Poland, contributed to the country's linguistic homogeneity.

Polish-speakers use the language in a uniform manner throughout most of Poland, though numerous languages and dialects coexist alongside the standard Polish language. The most common dialects in Poland are Silesian, spoken in Upper Silesia, and Kashubian, widely spoken in the north.

Science and technology

Education has been of prime interest to Poland since the early 12th century. The catalog of the library of the Cathedral Chapter in Kraków dating from 1110 shows that Polish scholars already then had access to literature from all over Europe. In 1364 King Casimir III the Great founded the Kraków Academy, which would become Jagiellonian University, one of the great universities of Europe.

The list of early famous scientists in Poland begins with the 13th-century Witelo and includes the polymath and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who formulated a model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than the Earth at its center; the publication of Copernicus' book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) just before his death in 1543 is considered a major event in the history of science, triggering the Copernican Revolution and making an important contribution to the Scientific Revolution. In 1773 King Stanisław August Poniatowski established the Commission of National Education, the world's first ministry of education.

After the 1795 third partition of Poland, no free Polish state existed. The 19th and 20th centuries saw many Polish scientists working abroad. The greatest was Maria Skłodowska Curie (1867–1934), a physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity and was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person and only woman to win twice, the only person to win twice in multiple sciences, and was part of the Curie family legacy of five Nobel Prizes. Another notable Polish expatriate scientist was Ignacy Domeyko (1802–89), a geologist and mineralogist who lived and worked in South America, in Chile.

Kazimierz Funk (1884–1967), whose name is commonly anglicized as "Casimir Funk", was a Polish biochemist, generally credited with being among the first to formulate (in 1912) the concept of vitamins, which he called "vital amines" or "vitamines".

In the first half of the 20th century, Poland was a world center of mathematics. Outstanding Polish mathematicians formed the Lwów School of Mathematics (including Stefan Banach, Hugo Steinhaus, Stanisław Ulam) and Warsaw School of Mathematics (including Alfred Tarski, Kazimierz Kuratowski, Wacław Sierpiński). World War II pushed many of them into exile; Benoit Mandelbrot's family left Poland when he was still a child. An alumnus of the Warsaw School of Mathematics was Antoni Zygmund, a shaper of 20th-century mathematical analysis.

Nicolaus Copernicus, astronomer who formulated a model of the Solar System that placed the Sun rather than the Earth at the centre.

Nicolaus Copernicus, astronomer who formulated a model of the Solar System that placed the Sun rather than the Earth at the centre. Michael Sendivogius, pioneer of chemistry, he discovered oxygen and developed ways of purification and creation of various acids, metals and other chemical compounds.

Michael Sendivogius, pioneer of chemistry, he discovered oxygen and developed ways of purification and creation of various acids, metals and other chemical compounds. Ignacy Łukasiewicz, pharmacist and petroleum industry pioneer who built the world's first oil refinery, invented the modern kerosene lamp, and introduced the first modern street lamp in Europe.

Ignacy Łukasiewicz, pharmacist and petroleum industry pioneer who built the world's first oil refinery, invented the modern kerosene lamp, and introduced the first modern street lamp in Europe. Marie Skłodowska Curie, conducted pioneering research on radioactivity and was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize.

Marie Skłodowska Curie, conducted pioneering research on radioactivity and was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize. Tadeusz Reichstein, succeeded in synthesizing vitamin C in what is now called the Reichstein process and received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Tadeusz Reichstein, succeeded in synthesizing vitamin C in what is now called the Reichstein process and received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Marian Rejewski, mathematician and cryptologist who reconstructed the Nazi German military Enigma cipher machine sight-unseen in 1932.

Marian Rejewski, mathematician and cryptologist who reconstructed the Nazi German military Enigma cipher machine sight-unseen in 1932. Wacław Sierpiński, a Polish mathematician known for outstanding contributions to set theory (research on the axiom of choice and the continuum hypothesis), number theory, theory of functions and topology

Wacław Sierpiński, a Polish mathematician known for outstanding contributions to set theory (research on the axiom of choice and the continuum hypothesis), number theory, theory of functions and topology Hilary Koprowski, virologist and immunologist, and the inventor of the world's first effective live polio vaccine.

Hilary Koprowski, virologist and immunologist, and the inventor of the world's first effective live polio vaccine. Leonid Hurwicz, the first economist to recognize the value of game theory and the oldest Nobel Laureate, having received the prize at the age of 90.

Leonid Hurwicz, the first economist to recognize the value of game theory and the oldest Nobel Laureate, having received the prize at the age of 90. Benoit Mandelbrot, recognized for his contribution to the field of fractal geometry, as well as developing a theory of "roughness and self-similarity" in nature.

Benoit Mandelbrot, recognized for his contribution to the field of fractal geometry, as well as developing a theory of "roughness and self-similarity" in nature. Stefan Banach, one of the most influential mathematicians of the 20th century, one of the principal founders of modern functional analysis

Stefan Banach, one of the most influential mathematicians of the 20th century, one of the principal founders of modern functional analysis Stanisław Ulam, mathematician; he participated in America's Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, discovered the concept of cellular automaton, invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion

Stanisław Ulam, mathematician; he participated in America's Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, discovered the concept of cellular automaton, invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion Krzysztof Matyjaszewski, chemist, recipient of Wolf Prize in chemistry, best known for the discovery of atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), a novel method of polymer synthesis that has revolutionized the way macromolecules are made

Krzysztof Matyjaszewski, chemist, recipient of Wolf Prize in chemistry, best known for the discovery of atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), a novel method of polymer synthesis that has revolutionized the way macromolecules are made Aleksander Wolszczan, astronomer, he conducted pioneering astronomical observations and co-discovered the first extrasolar planets and pulsar planets

Aleksander Wolszczan, astronomer, he conducted pioneering astronomical observations and co-discovered the first extrasolar planets and pulsar planets

Marian Rejewski (1905–80), a Polish mathematician, in December 1932 solved the plugboard-equipped Enigma machine, the main cipher device used by Nazi Germany. The cryptologic successes of Rejewski and his mathematician colleagues Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski, over six and a half years later, jump-started British reading of Enigma in the Second World War; the intelligence so gained, code-named Ultra, contributed, perhaps decisively, to the defeat of Germany.[45]

Sir Józef Rotblat (1908–2005), a Polish physicist, who left the U.S. Manhattan Project on grounds of conscience. His work on nuclear fallout was a major contribution toward the ratification of the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. A signatory of the Russell–Einstein Manifesto, he was secretary-general of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs from their founding until 1973. He shared, with the Pugwash Conferences, the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize for efforts toward nuclear disarmament.[46][47][48][49][50]

Hilary Koprowski (1916 – 2013) was a Polish virologist and immunologist, and the inventor of the world's first effective live polio vaccine. While in the United States, he authored or co-authored over 875 scientific papers and co-edited several scientific journals. Aleksander Wolszczan (born 1946), a Polish astronomer, is the co-discoverer of the first extrasolar planets and pulsar planets.

Today Poland has over 100 institutions of post-secondary education – technical, medical, economic, as well as 500 universities – located in major cities such as Gdańsk, Kraków, Wrocław, Lublin, Łódź, Poznań, Rzeszów and Warsaw. They employ over 61,000 scientists and scholars. Another 300 research-and-development institutes are home to some 10,000 researchers. There are also a number of smaller laboratories. Altogether, these institutions support some 91,000 scientists and scholars.

Music

| Józef Hofmann (1876–1957) |

Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937) |

Arthur Rubinstein (1887–1982) |

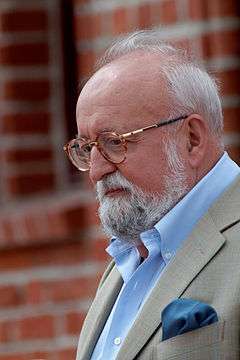

Krzysztof Penderecki (born 1933) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |  |  |

The origin of Polish music can be traced as far back as the 13th century, from which manuscripts have been found in Stary Sącz, containing polyphonic compositions related to the Parisian Notre Dame School. Other early compositions, such as the melody of Bogurodzica, may also date back to this period. The first known notable composer, however, Mikołaj z Radomia, lived in the 15th century.

During the 16th century, mostly two musical groups—both based in Kraków and belonging to the King and Archbishop of Wawel—led the rapid innovation of Polish music. Composers writing during this period include Wacław of Szamotuły, Mikołaj Zieleński, and Mikołaj Gomółka. Diomedes Cato, a native-born Italian who lived in Kraków from about the age of five, became one of the most famous lutenists at the court of Sigismund III, and not only imported some of the musical styles from southern Europe, but blended them with native folk music.[51]

17th and 18th centuries

|

Pożegnanie Ojczyzny (Farewell to Country)

Polonaise by Ogiński |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

In the last years of the 16th century and the first part of the 17th century, a number of Italian musicians were guests at the royal courts of King Sigismund III Vasa and his son Władysław IV. These included Luca Marenzio, Giovanni Francesco Anerio, and Marco Scacchi. Polish composers from this period focused on baroque religious music, concertos for voices, instruments, and basso continuo, a tradition that continued into the 18th century. The best-remembered composer of this period is Adam Jarzębski, known for his instrumental works such as Chromatica, Tamburetta, Sentinella, Bentrovata, and Nova Casa. Other composers include Grzegorz Gerwazy Gorczycki, Franciszek Lilius, Bartłomiej Pękiel, Stanisław Sylwester Szarzyński and Marcin Mielczewski.

In addition, a tradition of operatic production began in Warsaw in 1628, with a performance of Galatea (composer uncertain), the first Italian opera produced outside Italy. Shortly after this performance, the court produced Francesca Caccini's opera La liberazione di Ruggiero dall'isola d’Alcina, which she had written for Prince Władysław three years earlier when he was in Italy. Another first, this is the earliest surviving opera written by a woman. When Władysław became king (as Władysław IV) he oversaw the production of at least ten operas during the late 1630s and 1640s, making Warsaw a center of the art. The composers of these operas are not known: they may have been Poles working under Marco Scacchi[52] in the royal chapel, or they may have been among the Italians imported by Władysław.

The late 17th and 18th century saw a decline of Poland, which also hindered the development of music. Some composers attempted to create a Polish opera (such as Jan Stefani and Maciej Kamieński), others imitated foreign composers such as Haydn and Mozart.

The most important development in this time, however, was the polonaise, perhaps the first distinctively Polish art music. Polonaises for piano were and remain popular, such as those by Michał Kleofas Ogiński, Karol Kurpiński, Juliusz Zarębski, Henryk Wieniawski, Mieczysław Karłowicz, Józef Elsner, and, most famously, Fryderyk Chopin. Chopin remains very well known, and is regarded for composing a wide variety of works, including mazurkas, nocturnes, waltzes and concertos, and using traditional Polish elements in his pieces. The same period saw Stanisław Moniuszko, the leading individual in the successful development of Polish opera, still renowned for operas like Halka and The Haunted Manor.

_.jpg) Michał Kleofas Ogiński, known for his polonaise Pożegnanie Ojczyzny, written on the occasion of his emigration after the failure of the Kościuszko Uprising.

Michał Kleofas Ogiński, known for his polonaise Pożegnanie Ojczyzny, written on the occasion of his emigration after the failure of the Kościuszko Uprising.- Frédéric Chopin, whose innovations in style, musical form and harmony, and his association of music with nationalism, were influential throughout the Romantic period.

.jpg) Stanisław Moniuszko, wrote many popular art songs and operas, and his music is filled with patriotic folk themes of the peoples of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

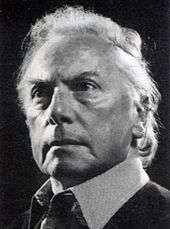

Stanisław Moniuszko, wrote many popular art songs and operas, and his music is filled with patriotic folk themes of the peoples of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Witold Lutosławski, one of the major European composers of the 20th century, and one of the preeminent Polish musicians during his last three decades.

Witold Lutosławski, one of the major European composers of the 20th century, and one of the preeminent Polish musicians during his last three decades. Andrzej Panufnik, one of the leading Polish composers responsible for the re-establishment of the Warsaw Philharmonic orchestra after World War II.

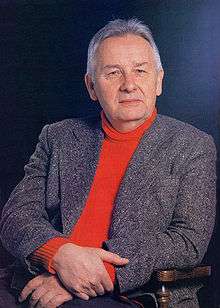

Andrzej Panufnik, one of the leading Polish composers responsible for the re-establishment of the Warsaw Philharmonic orchestra after World War II. Henryk Górecki, became a leading figure of the Polish avant-garde during the post-Stalin cultural thaw and achieved great commercial success.

Henryk Górecki, became a leading figure of the Polish avant-garde during the post-Stalin cultural thaw and achieved great commercial success.

Traditional music

|

Waltz in D-flat major, Op. 64, No. 1 (so-called Minute Waltz)

Muriel Nguyen Xuan, piano |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Polish folk music was collected in the 19th century by Oskar Kolberg, as part of a wave of Polish national revival.[53] With the coming of the world wars and then the Communist state, folk traditions were oppressed or subsumed into state-approved folk ensembles.[54] The most famous of the state ensembles are Mazowsze and Śląsk, both of which still perform. Though these bands had a regional touch to their output, the overall sound was a homogenized mixture of Polish styles. There were more authentic state-supported groups, such as Słowianki, but the Communist sanitized image of folk music made the whole field seem unhip to young audiences, and many traditions dwindled rapidly.

Polish dance music, especially the mazurka and polonaise, were popularized by Frédéric Chopin, and they soon spread across Europe and elsewhere.[54] These are triple time dances, while five-beat forms are more common in the northeast and duple-time dances like the krakowiak come from the south. The polonaise comes from the French word for Polish to identify its origin among the Polish aristocracy and nobility, who had adapted the dance from a slower walking dance called chodzony.[54] The polonaise then re-entered the lower-class musical life, and became an integral part of Polish music.

Literature

Polish literature is the literary tradition of Poland. Most Polish literature has been written in the Polish language, though other languages, used in Poland over the centuries, have also contributed to Polish literary traditions, including German, Hungarian, Slovak, Czech, Latin, Yiddish, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and Esperanto.

Middle Ages

Almost nothing remains of Polish literature prior to the country's Christianization in 966. Poland's pagan inhabitants certainly possessed an oral literature extending to Slavic songs, legends and beliefs, but early Christian writers did not deem it worthy of mention in the obligatory Latin, and so it has perished.[55]

The first recorded sentence in the Polish language reads: "Day ut ia pobrusa, a ti poziwai" ("Let me grind, and you take a rest") – a paraphrase of the Latin "Sine, ut ego etiam molam." The work, in which this phrase appeared, reflects the culture of early Poland. The sentence was written within the Latin language chronicle Liber fundationis from between 1269 and 1273, a history of the Cistercian monastery in Henryków, Silesia. It was recorded by an abbot known simply as Piotr (Peter), referring to an event almost a hundred years earlier. The sentence was supposedly uttered by a Bohemian settler, Bogwal ("Bogwalus Boemus"), a subject of Bolesław the Tall, expressing compassion for his own wife who "very often stood grinding by the quern-stone."[56] Most notable early medieval Polish works in Latin and the Old Polish language include the oldest extant manuscript of fine prose in the Polish language entitled the Holy Cross Sermons, as well as the earliest Polish-language Bible of Queen Zofia and the Chronicle of Janko of Czarnków from the 14th century, not to mention the Puławy Psalter.[55]

In the early 1470s, one of the first printing houses in Poland was set up by Kasper Straube in Kraków (see: spread of the printing press). In 1475 Kasper Elyan of Glogau (Głogów) set up a printing shop in Breslau (Wrocław), Silesia. Twenty years later, the first Cyrillic printing house was founded at Kraków by Schweipolt Fiol for Eastern Orthodox Church hierarchs. The most notable texts produced in that period include Saint Florian's Breviary, printed partially in Polish in the late 14th century; Statua synodalia Wratislaviensia (1475): a printed collection of Polish and Latin prayers; as well as Jan Długosz's Chronicle from the 15th century and his Catalogus archiepiscoporum Gnesnensium.[55]

Renaissance

With the advent of the Renaissance, the Polish language was finally accepted on an equal footing with Latin. Polish culture and art flourished under Jagiellonian rule, and many foreign poets and writers settled in Poland, bringing with them new literary trends. Such writers included Kallimach (Filippo Buonaccorsi) and Conrad Celtis. Many Polish writers studied abroad, and at the Kraków Academy, which became a melting pot for new ideas and currents. In 1488 the world's first writers' club, called Sodalitas Litterarum Vistulana was founded in Kraków. Notable members included Conrad Celtes, Albert Brudzewski, Filip Callimachus and Laurentius Corvinus.[55]

Baroque

Polish Baroque literature[57] (1620–1764) was influenced by the popularization of Jesuit secondary schools, which offered an education based on Latin classics as part of a preparation for a career in politics. The study of poetry required practical skill in writing both Latin and Polish poems, and radically increased the numbers of poets and versifiers countrywide. Some exceptional writers grew up as well in the soil of humanistic education: Piotr Kochanowski (1566–1620) produced a translation of Torquato Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered; poet laureate Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski became known throughout Europe, for his Latin writings, as Horatius christianus ("the Christian Horace"); Jan Andrzej Morsztyn (1621–1693), epicurean courtier and diplomat, extolled in his sophisticated poems the value of earthly delights; and Wacław Potocki (1621–96), the most productive writer of the Polish Baroque, united typical Polish szlachta (nobility) views with deeper reflections and existential experiences. Notable Polish poets and prose writers of the period included:

|

|

Enlightenment

The period of Polish Enlightenment began in the 1730s–40s and peaked in the second half of the 18th century during the reign of Poland's last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski.[59] It went into sharp decline with the Third and final Partition of Poland (1795), followed by political, cultural and economic destruction of the country, and leading to the Great Emigration of Polish elites. The Enlightenment ended around 1822, and was replaced by Polish Romanticism at home and abroad.[55] The crowning achievements of Polish Enlightenment include the adoption of the Constitution of May 3, 1791, Europe's oldest written constitution as well as the creation of the Commission of National Education, the world's first ministry of education.

One of the leading Polish Enlightenment poets was Ignacy Krasicki (1735–1801), known as "the Prince of Poets" and Poland's La Fontaine, author of Fables and Parables as well as the first Polish novel called The Adventures of Mr. Nicholas Wisdom (Mikołaja Doświadczyńskiego przypadki); he was also a playwright, journalist, encyclopedist and translator from French and Greek. Another prominent writer of the period was Jan Potocki (1761–1815), a Polish nobleman, Egyptologist, linguist, and adventurer, whose travel memoirs made him legendary in his homeland. Outside Poland he is known chiefly for his novel, The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, which has drawn comparisons to such celebrated works as the Decameron and the Arabian Nights.

Another notable literary figure from this period is Piotr Skarga, a Polish Jesuit, preacher, hagiographer, polemicist, and leading figure of the Counter-Reformation in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. His greatest works include The Lives of the Saints (Żywoty świętych, 1579), which was for several centuries one of the most popular books in the Polish language and the Sejm Sermons (Kazania Sejmowe, 1597), a political treatise, which became popular in the second half of the 19th century, when Skarga was seen as the "patriotic seer" who predicted the partitions of Poland.

Romanticism

Due to the three successive Partitions carried out by three adjacent empires—ending the existence of the sovereign Polish state in 1795—Polish Romanticism, unlike Romanticism elsewhere in Europe, was largely a movement for independence from foreign occupation, and expressed the ideals and traditional way of life of the Polish people. The period of Romanticism in Poland ended with the Russian Empire's suppression of the January 1863 Uprising, culminating in public executions and deportations to Siberia.[60]

The literature of Polish Romanticism falls into two distinct sub-periods, each ended by an insurgency: the first, circa 1820–30, ending with the November 1830 Uprising; and the second, 1830–64, giving rise to Polish Positivism. In the first Romantic sub-period, Polish Romantics were heavily influenced by other European Romantics: their work featured emotionalism and imagination, folklore, and country life, in addition to the aspiration for independence. The sub-period's most famous writers were Adam Mickiewicz, Seweryn Goszczyński, Tomasz Zan, and Maurycy Mochnacki.

In the second Romantic sub-period, after the November 1830 Uprising, many Polish Romantics worked abroad, driven from Poland by the occupying powers. Their work became dominated by the aspiration to regain their country's lost sovereignty. Elements of mysticism became more prominent. Also, the concept of the Three Bards (trzej wieszcze) developed. The wieszcz functioned as spiritual leader to the suppressed people. The most notable poet of the Three Bards, so recognized in both Polish Romantic sub-periods, was Adam Mickiewicz. The other two national bards were Juliusz Słowacki and Zygmunt Krasiński.

- Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, President of the Polish National Government during the November 1830 Uprising, and a romantic poet.

- Aleksander Fredro, whose fables, prose, and especially plays belong to the canon of Polish literature.

Adam Mickiewicz, a principal figure in Polish Romanticism, widely regarded as one of the greatest Polish and European poets of all time.

Adam Mickiewicz, a principal figure in Polish Romanticism, widely regarded as one of the greatest Polish and European poets of all time.- Zygmunt Krasiński, one of the Three Bards who influenced national consciousness during Poland's political bondage.

- Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, author of An Ancient Tale, who produced over 200 novels and 150 novellas.

- Juliusz Słowacki, a major figure of Polish Romanticism, and father of modern Polish drama. His most popular works include Kordian and Balladyna.

.jpg) Cyprian Kamil Norwid, a nationally esteemed poet, sometimes considered to be the "Fourth Bard".

Cyprian Kamil Norwid, a nationally esteemed poet, sometimes considered to be the "Fourth Bard".

Positivism

In the wake of the failed January 1863 Uprising against Russian occupation, a new period of thought and literature, Polish "Positivism", proceeded to advocate level-headedness, skepticism, the exercise of reason, and "organic work". "Positivist" writers argued for the establishment of equal rights for all members of society; for the assimilation of Poland's Jewish minority; and for defense of western Poland's population, in the German-occupied part of Poland, against the German Kulturkampf and the displacement of the Polish populace by German colonization. Writers such as Bolesław Prus sought to educate the public about a constructive patriotism that would enable Polish society to function as a fully integrated social organism, regardless of external circumstances.[61] Another influential Polish novelist active in that period was Henryk Sienkiewicz who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1905. The Positivist period lasted until the turn of the 20th century and the advent of the Young Poland movement.

Young Poland (1890–1918)

The modernist period known as the Young Poland movement in visual arts, literature and music, came into being around 1890, and concluded with the Poland's return to independence (1918). The period was based on two concepts. Its early stage was characterized by a strong aesthetic opposition to the ideals of its own predecessor (promoting organic work in the face of foreign occupation). Artists following this early philosophy of Young Poland believed in decadence, symbolism, conflict between human values and civilization, and the existence of art for art's sake. Prominent authors who followed this trend included Joseph Conrad, Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer, Stanisław Przybyszewski and Jan Kasprowicz.

Interbellum and the return to independence (1918–1939)

Literature of the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939) encompasses a short, though exceptionally dynamic period in Polish literary consciousness. The socio-political reality has changed radically with Poland's return to independence. In large part, derivative of these changes was the collective and unobstructed development of programs for artists and writers. New avant-garde trends had emerged. The period, spanning just twenty years, was full of notable individualities who saw themselves as exponents of changing European civilization, including Tuwim, Witkacy, Gombrowicz, Miłosz, Dąbrowska and Nałkowska (PAL).

After 1945

Much of Polish literature written during the occupation of Poland appeared in print only after the end of World War II, including books by Nałkowska, Rudnicki, Borowski and others.[62] The Soviet takeover of the country did not discourage émigrés and exiles from returning, especially before the advent of Stalinism. Indeed, many writers attempted to recreate the Polish literary scene, often with a touch of nostalgia for the prewar reality, including Jerzy Andrzejewski, author of Ashes and Diamonds, describing the political and moral dilemmas associated with the anti-communist resistance in Poland. His novel was adapted into film a decade later by Wajda. The new emerging prose writers such as Stanisław Dygat and Stefan Kisielewski approached the catastrophe of war from their own perspective. Kazimierz Wyka coined a term "borderline novel" for documentary fiction.[62]

In the second half of the 20th century a number of Polish writers and poets achieved international recognition including Stanisław Lem, Czesław Miłosz (Nobel Prize in Literature, 1980), Zbigniew Herbert, Sławomir Mrożek, Wisława Szymborska (Nobel Prize in Literature, 1996), Jerzy Kosiński, Adam Zagajewski, Andrzej Sapkowski, and Olga Tokarczuk.

Poles in cinema and theatre

At present, the Polish theatre actor possibly best-known outside the country is Andrzej Seweryn, who in the years 1984–1988 was a member of the international group formed by Peter Brook to work on the staging of the Mahabharata, and since 1993 has been linked with the Comédie Française. The most revered actor of the second half of the twentieth century in Poland is generally considered to be Tadeusz Łomnicki, who died in 1992 of a heart attack while rehearsing King Lear.

During the second half of the nineties, there appeared in Polish dramatic theatre a new generation of young directors, who have attempted to create productions relevant to the experience and problems of a thirty-something generation brought up surrounded by mass culture, habituated to a fast-moving lifestyle, but at the same time ever more lost in the world of consumer capitalism. There is no strict division in Poland between theatre and film directors and actors, therefore many stage artists are known to theatre goers from films of Andrzej Wajda, for example: Wojciech Pszoniak, Daniel Olbrychski, Krystyna Janda, Jerzy Radziwiłowicz, and from films of Krzysztof Kieślowski. Notable actors from Poland include Jerzy Stuhr, Janusz Gajos, Jerzy Skolimowski and Michał Żebrowski. Polish actors and actresses that achieved great success overseas, mostly in Hollywood, include Bella Darvi, Pola Negri, Ross Martin, Ingrid Pitt, Ned Glass, Lee Strasberg, Izabella Scorupco, Paul Wesley and John Bluthal.

Notable Hollywood American actors and actresses of Polish descent include David Arquette, Caroll Baker (born Karolina Piekarski), Christine Baranski, Kristen Bell, Maria Bello, Jack Benny, Charles Bronson, Mayim Bialik, Cate Blanchett, Alex Borstein, David Burtka, Steve Carell, Anna Chlumsky, Jennifer Connelly, Jesse Eisenberg, Estelle Getty, Scarlett Johansson, Harvey Keitel, John Krasinski, Lisa Kudrow, Ben Stiller, Carole Landis, Téa Leoni, Paul Newman, Eli Wallach, Jared Padalecki, Gwyneth Paltrow, Robert Prosky, Maggie Q, William Shatner, Sarah Silverman, Leelee Sobieski, Loretta Swit and others.[63]

Lee Strasberg, co-founder of the New York Group Theatre, which was hailed as "America's first true theatrical collective"

Lee Strasberg, co-founder of the New York Group Theatre, which was hailed as "America's first true theatrical collective".jpg) Andrzej Wajda, recipient of a honorary Oscar and the Palme d'Or, he was possibly the most prominent member of the "Polish Film School"

Andrzej Wajda, recipient of a honorary Oscar and the Palme d'Or, he was possibly the most prominent member of the "Polish Film School" Carroll Baker, earned her BAFTA and Academy Award nomination for Tennessee Williams's Baby Doll (1956)

Carroll Baker, earned her BAFTA and Academy Award nomination for Tennessee Williams's Baby Doll (1956) Roman Polanski, film director and Academy Award winner. Known for Rosemary's Baby, Chinatown (1974), The Pianist (2002) and Oliver Twist (2005).

Roman Polanski, film director and Academy Award winner. Known for Rosemary's Baby, Chinatown (1974), The Pianist (2002) and Oliver Twist (2005). Andrzej Seweryn, one of the most successful Polish theatre actors, starred in over 50 films

Andrzej Seweryn, one of the most successful Polish theatre actors, starred in over 50 films Paul Wesley, known for playing Aaron Corbett in Fallen and Stefan Salvatore in the supernatural drama The Vampire Diaries

Paul Wesley, known for playing Aaron Corbett in Fallen and Stefan Salvatore in the supernatural drama The Vampire Diaries Krzysztof Kieślowski, an influential filmmaker, his most critically acclaimed films include Dekalog, The Double Life of Veronique and Three Colors trilogy

Krzysztof Kieślowski, an influential filmmaker, his most critically acclaimed films include Dekalog, The Double Life of Veronique and Three Colors trilogy Mia Wasikowska, Australian actress of Polish descent, known for her roles in such films as Alice in Wonderland, Jane Eyre, Maps to the Stars and Alice Through the Looking Glass

Mia Wasikowska, Australian actress of Polish descent, known for her roles in such films as Alice in Wonderland, Jane Eyre, Maps to the Stars and Alice Through the Looking Glass.jpg)

Jerzy Skolimowski, film director, recipient of Golden Bear Award and Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement

Jerzy Skolimowski, film director, recipient of Golden Bear Award and Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement_crop.jpg) Agnieszka Holland, film and television director, and screenwriter, best known for her political contributions to Polish cinema, Holland is one of Poland's most eminent filmmakers

Agnieszka Holland, film and television director, and screenwriter, best known for her political contributions to Polish cinema, Holland is one of Poland's most eminent filmmakers

Religion

Most Poles adhere to the Christian faith, the majority belonging to the Roman Catholic Church.[64] with 87.5% of Poles in 2011 identifying as Roman Catholic.[35] The remaining religious part of the population consists mainly of Protestants, Lutherans, Jehovah's Witnesses, those irreligious, and Judaism (mostly from the Jewish populations in Poland who have lived there prior to World War II).[65] Roman Catholics live all over the country, while Orthodox Christians can be found mostly in north-east, in the area of Białystok, and Protestants (mainly Lutherans) in Cieszyn Silesia and Warmia-Masuria. A growing Jewish population exists in major cities, especially in Warsaw, Kraków and Wrocław. Over two million Jews of Polish origin reside in the United States, Brazil, and Israel.

According to Poland's Constitution freedom of religion is ensured to everyone. It also allows for national and ethnic minorities to have the right to establish educational and cultural institutions, institutions designed to protect religious identity, as well as to participate in the resolution of matters connected with their cultural identity.

Religious organizations in the Republic of Poland can register their institution with the Ministry of Interior and Administration creating a record of churches and other religious organizations who operate under separate Polish laws. This registration is not necessary; however, it is beneficial when it comes to serving the freedom of religious practice laws.

The Slavic Rodzimowiercy groups, registered with the Polish authorities in 1995, are the Native Polish Church (Rodzimy Kościół Polski) which represents a pagan tradition that goes back to Władysław Kołodziej's 1921 Holy Circle of Worshipper of Światowid (Święte Koło Czcicieli Światowida), and the Polish Slavic Church (Polski Kościół Słowiański),[66] There's also the Native Faith Association (Zrzeszenie Rodzimej Wiary, ZRW), and the Association for Tradition and Culture Niklot (founded in 1998).

Exonyms

Among the exonyms not native to the Polish people or language are: лях (lyakh) used in East Slavic languages. Today, the word Lachy is used in Belorussian, Ukrainian (now considered offensive and is replaced by the neutral поляк – polyak) and Russian as synonyms for "Poles". The foreign exonyms include also: Lithuanian Lenkai, Hungarian Lengyelek, Turkish Leh, Armenian: Լեհաստան Lehastan; Persian: لهستان Lahestān.

See also

- Polonization

- Karta Polaka

- Polish nationality law

- Demographics of Poland

- List of Poles

- West Slavs

- Lechites

- Name of Poland (etymology of the demonym)

- Pole, Hungarian, two good friends

- Poles in Germany

- Poles in Lithuania

- Poles in Romania

- Poles in the former USSR

- Poles in the United Kingdom

- Polish Americans

- Polish Argentines

- Polish Australians

- Polish Brazilians

- Polish British

- Polish Canadians

- Polish Chileans

- Polish Czechs

- Polish minority in France

- Polish Mexicans

- Polish New Zealanders

- Polish Spaniards

- Polish Uruguayan

- Polish Venezuelans

- Sons of Poland

References

- 1 2 Central Statistical Office (January 2013). "The national-ethnic affiliation in the population – The results of the census of population and housing in 2011" (PDF) (in Polish). p. 1. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ p. 5

- ↑ Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska

- ↑ http://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2016-06/polen-deutschland-einwanderung-integration

- ↑ "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wspólnota Polska. "Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Polish diaspora in numbers" (in Polish). association "Polish Community". Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ British Office for National Statistics, Population by Country of Birth & Nationality, Jan 2009 to Dec 2009 with immigrants for 2012

^ Please note: The British Office for National Statistics recorded the number of Poles who have travelled to the UK in 2006 at over 2,000,000; they are not to be mistaken for permanent residents. - ↑ "Clarín.com – La ampliación de la Unión Europea habilita a 600 mil argentinos para ser comunitarios". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ 2006 Census Community Profile Series : Australia

- ↑

- ↑ "Ukrainian Census 2001". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Census 2011 Results

- ↑ "- 120.000 polakker i Norge". Aftenposten. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "ISTAT" (PDF). Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "Befolkning efter födelseland och ursprungsland 31 december 2012" (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ↑ Instituto Nacional de Estadística Population Figures at 1 January 2014 – Migration Statistics 2013

- ↑ "". External link in

|title=(help); - ↑ Czech Republic National Census 2001 (PDF)

- ↑ "On key provisional results of Population and Housing Census 2011". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Statistics Denmark:FOLK1: Population at the first day of the quarter by sex, age, ancestry, country of origin and citizenship". Statistics Denmark. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ↑ Kazakhstan National Census 2009

- ↑ Wspólnota Polska. "Stowarzyszenie Wspólnota Polska". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Ante la crisis, Europa y el mundo miran a Latinoamérica" (in Spanish). Acercando Naciones. 2012.

- ↑ Mannfjöldi eftir fæðingarlandi 1981–2008: Pólland

- ↑ Joshua Project. "Country – Venezuela :: Joshua Project". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Erwin Dopf. "Migraciones europeas minoritarias". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ 2011 Census of Hungary

- ↑ 2004 Moldovan census, including Transnistria

- ↑ 2002 Romanian census.

- ↑ http://portal.statistics.sk/files/tab.11.pdf

- ↑ "Placówki Dyplomatyczne Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ 2013 Census ethnic group profiles: Polish

- ↑ "Population by ethnic nationality". Statistics Estonia. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- 1 2 GUS, Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludnosci 2011: 4.4. Przynależność wyznaniowa (National Survey 2011: 4.4 Membership in faith communities) p. 99/337 (PDF file, direct download 3.3 MB). ISBN 978-83-7027-521-1 Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Gerard Labuda. Fragmenty dziejów Słowiańszczyzny zachodniej, t.1–2 p.72 2002; Henryk Łowmiański. Początki Polski: z dziejów Słowian w I tysiącleciu n.e., t. 5 p.472; Stanisław Henryk Badeni, 1923. p. 270.

- 1 2 Davies 2005a, p. xxvii.

- ↑ Derwich & Żurek 2002, pp. 122–143.

- ↑ Norman Davies Poland's Multicultural Heritage

- ↑ NationMaster.com 2003–2008. People Statistics: Population (most recent) by country. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ↑ Gil Loescher, Beyond Charity: International Cooperation and the Global Refugee Crisis, published by the University of Oxford Press US, 1993, 1996. ISBN 0-19-510294-0. Retrieved 12-12-2007.

- ↑ http://wiadomosci.onet.pl/swiat/sueddeutsche-zeitung-polska-przezywa-najwieksza-fale-emigracji-od-100-lat/yrtt0"Sueddeutsche Zeitung": Polska przeżywa największą falę emigracji od 100 lat

- ↑ Adam Zamoyski, The Polish Way: A Thousand Year History of the Poles and Their Culture. Published 1993, Hippocrene Books, Poland, ISBN 0-7818-0200-8

- 1 2 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, 2002–2007, AN OVERVIEW OF POLISH CULTURE. Access date 13 December 2007.

- ↑ Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower called Ultra "decisive" to Allied victory. F.W. Winterbotham, The Ultra Secret, New York, Harper & Row, 1974, ISBN 0-06-014678-8, pp. 16–17. For a fuller discussion, see "Ultra".

- ↑ Landau, S. (1996) Profile: Joseph Rotblat – From Fission Research to a Prize for Peace, Scientific American 274(1), 38–39.

- ↑ Poles's publications indexed by the Scopus bibliographic database, a service provided by Elsevier. (subscription required)

- ↑ Holdren, J. P. (2005). "Retrospective: Joseph Rotblat (1908–2005)". Science. 310 (5748): 633. PMID 16254178. doi:10.1126/science.1121081.

- ↑ "Joseph Rotblat BBC Radio 4 Desert Island Discs Castaway 1998-11-08". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013.

- ↑ "Rotblat, Sir Joseph (1908–2005)". The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/96004.

- ↑ "The Music Courts of the Polish Vasas" (PDF). www.semper.pl. p. 244. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ↑ "Marco Scacchi". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Broughton 2000, p. 219.

- 1 2 3 Ibidem, p. 219.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Czesław Miłosz, The History of Polish Literature. Google Books preview. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1983. ISBN 0-520-04477-0. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ↑ Mikoś, Michael J. (1999). "MIDDLE AGES LITERARY BACKGROUND". Staropolska on-line. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- ↑ Stanisław Barańczak, Baroque in Polish poetry of the 17th century. Instytut Książki, Poland. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ↑ Karol Badecki, "Pisma Jana Dzwonowskiego (1608–1625)." Wydawnictwa Akademii Umiejętności w Krakowie. Biblioteka Pisarzów Polskich. Kraków. Nakładem Akademii Umiejętności. 1910. 119s. (in Polish)

- ↑ Jacek Adamczyk, book review: Regina Libertas: Liberty in Polish Eighteenth-Century Political Thought, by Anna Grześkowiak-Krwawicz. Instytut Książki, Poland. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ↑ Day, William Ansell (1867). The Russian government in Poland: with a narrative of the Polish Insurrection of 1863. London : Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer.

- ↑ Czesław Miłosz, The History of Polish Literature, p. 284.

- 1 2 Jean Albert Bédé, William Benbow Edgerton, Columbia dictionary of modern European literature. Page 632. Columbia University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-231-03717-1

- ↑ "IMDb: Actors and Actresses of Polish Descent – a list by comicman117". IMDb. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ (in Polish) Kościoły i związki wyznaniowe w Polsce. Retrieved on June 17, 2008.

- ↑ Simpson, Scott (2000). Native Faith: Polish Neo-Paganism At the Brink of the 21st Century

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People of Poland. |

.jpg)