Estrone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular, vaginal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: Very low |

| Protein binding |

96%:[1][2] • Albumin: 80% • SHBG: 16% • Free: 2–4% |

| Metabolism | Liver (via hydroxylation, sulfation, glucuronidation)[1] |

| Biological half-life | IV: 20–30 minutes[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.150 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H22O2 |

| Molar mass | 270.366 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 254.5 °C (490.1 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Estrone (E1), also spelled oestrone, is a steroid, a weak estrogen, and a minor female sex hormone.[1] It is one of three major endogenous estrogens, the others being estradiol and estriol.[1] Estrone, as well as the other estrogens, are synthesized from cholesterol and secreted mainly from the gonads, though they can also be formed from adrenal androgens in adipose tissue.[3] Relative to estradiol, both estrone and estriol have far weaker activity as estrogens.[1] Previously, estrone was available as an injected estrogen for medical use, but it is now no longer marketed.[4]

Biological effects

In the 1930s, estrone was given via intramuscular injection to ovariectomized women in order to study its effects and to elucidate the biological properties of estrogens in humans.[5][6][7] In these studies, prior to administration of estrone, amenorrhea, atrophy of the breasts (as well as flaccidity and small and non-erectile nipples), vagina, and endometrium, vaginal dryness, and subjective symptoms of ovariectomy (e.g., hot flashes, mood changes) were all present in the women.[5][6][7] Treatment with estrone was found to dose- and time-dependently produce a variety of effects, including breast changes, reproductive tract changes of the vagina, cervix, and endometrium/uterus, and relief from the subjective symptoms of ovariectomy, as well as increased libido.[5][6][7]

Breast changes specifically included enlargement and a sense of fullness, increased sensitivity and pigmentation of the nipples as well as nipple erection, tingling within the breast mammary glandular tissue, and aching and soreness of the breasts.[5][6][7] Reproductive tract changes included increased growth, thickness, and differentiation of the endometrium, and reversal of vaginal and cervical atrophy, which were accompanied by increased congestion of the cervix and mucous discharge from the cervix, uterine cramps and needle-like pains, pelvic fullness, a "bearing-down" sensation, and increased vaginal lubrication, as well as uterine bleeding both during treatment and in the days following cessation of injections.[5][6][7] Endometrial hyperplasia also occurred with sufficiently high dosages of estrone.[5][6][7]

Biological activity

Estrone is an estrogen, specifically an agonist of the estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ.[1][8] It is a far less potent estrogen than is estradiol, and as such is a relatively weak estrogen.[1][8] According to one in vitro study, the relative binding affinity of estrone for the human ERα and ERβ was 4% and 3.5% of that estradiol, respectively, and the relative transactivational capacity of estrone at the ERα and ERβ was 2.6% and 4.3% of that of estradiol, respectively.[8] In accordance, the estrogenic activity of estrone has been reported to be approximately 4% of that of estradiol.[1] In relation to the fact that estrone can be metabolized into estradiol, most of its potency in vivo is actually due to conversion into estradiol.[1]

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

Estrone is biosynthesized from cholesterol. The principal pathway involves androstenedione as an intermediate, with androstenedione being transformed into estrone by the enzyme aromatase. This reaction occurs in both the gonads and in certain other tissues, particularly adipose tissue, and estrone is subsequently secreted from these tissues.[3] In addition to aromatization of androstenedione, estrone is also formed reversibly from estradiol by the enzyme 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) in various tissues, including the liver, uterus, and mammary gland.[1]

Distribution

Estrone is bound approximately 16% to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and 80% to albumin in the circulation,[1] with the remainder (2.0 to 4.0%) circulating freely or unbound.[2] It has about 24% of the relative binding affinity of estradiol for SHBG.[1] As such, estrone is relatively poorly bound to SHBG.[10]

Metabolism

Estrone is conjugated into estrogen conjugates such as estrone sulfate and estrone glucuronide by sulfotransferases and glucuronidases, and can also be hydroxylated by cytochrome P450 enzymes into catechol estrogens such as 2-hydroxyestrone and 4-hydroxyestrone or into estriol.[1] Both of these transformations take place predominantly in the liver.[1] Estrone can also be reversibly converted into estradiol by 17β-HSD.[1]

Medical use

Estrone was previously marketed in intramuscular and vaginal formulations and was used in the treatment of symptoms of hypoestrogenism such as hot flashes and atrophic vaginitis in menopausal or ovariectomized women.[11] It has since been discontinued and is no longer available, having been superseded by other estrogens with greater potency and improved pharmacokinetics (namely oral bioavailability and duration).[4] Although estrone itself is no longer used medically, other marketed estrogens such as estradiol and estrone sulfate produce estrone as a major metabolite.[1]

Chemistry

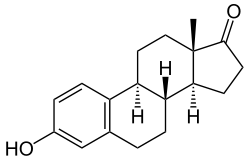

Estrone, also known as estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3-ol-17-one, is a naturally occurring estrane steroid with double bonds at the C1, C3, and C5 positions, a hydroxyl group at the C3 position, and a ketone group at the C17 position. The name estrone was derived from the chemical terms estrin (estra-1,3,5(10)-triene) and ketone.

The chemical formula of estrone is C18H22O2 and its molecular weight is 270.366 g/mol. It is a white, odorless, solid crystalline powder, with a melting point of 254.5 °C (490 °F) and a specific gravity of 1.23.[12][13] Estrone is combustible at high temperatures, with the products carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2).[12]

History

Estrone was the first steroid hormone to be discovered.[14][15] It was discovered in 1929 independently by the American scientists Edward Doisy and Edgar Allen and the German biochemist Adolf Butenandt, although Doisy and Allen isolated it two months before Butenandt.[14][16][17] They isolated and purified estrone in crystalline form from the urine of pregnant women.[16][17][18] Doisy and Allen named it theelin, while Butenandt named it progynon and subsequently referred to it as folliculin in his second publication on the substance.[17][19] Butenandt was later awarded the Nobel Prize in 1939 for the isolation of estrone and his work on sex hormones in general.[18][20] The molecular formula of estrone was known by 1931,[21] and its chemical structure had been determined by Butenandt by 1932.[17][16] Following the elucidation of its structure, estrone was additionally referred to as ketohydroxyestrin or oxohydroxyestrin,[22][11] and the name estrone was formally established in 1932 at the first meeting of the International Conference on the Standardization of Sex Hormones in London on the basis of its C17 ketone group.[23][24]

By 1931, estrone, purified from pregnancy urine, placentae, and/or amniotic fluid and for administration via intramuscular injection, was being sold commercially, for instance by Parke-Davis under the brand name Theelin in the United States and by Schering under the brand name Progynon in Germany.[14][11][25][26] Other products and brand names of purified estrone marketed by 1935 included Oestroform (British Drug Houses), Folliculin (Organon), and Menformon (Organon), as well as Amniotin (Squibb).[11][25] A partial synthesis of estrone from ergosterol was accomplished by Russell Earl Marker in 1936, and was the first chemical synthesis of estrone.[26][27] An alternative partial synthesis of estrone from cholesterol by way of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) was developed by Hans Herloff Inhoffen and Walter Hohlweg in 1939 or 1940,[26] and a total synthesis of estrone was achieved by Anner and Miescher in 1948.[24]

Society and culture

Generic name

Estrone is the generic name of estrone in American English and its INN, USP, BAN, DCF, DCIT, and JAN.[28][29][30][31] Oestrone, in which the "O" is silent, was the former BAN of estrone and its name in British English,[28][29][30] but the spelling was eventually changed to estrone.[31]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. PMID 16112947. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875.

- 1 2 J. Larry Jameson; Leslie J. De Groot (18 May 2010). Endocrinology - E-Book: Adult and Pediatric. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2813–. ISBN 1-4557-1126-8.

- 1 2 Theresa Hornstein; Jeri Lynn Schwerin (1 January 2012). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. pp. 369–. ISBN 1-285-40102-6.

- 1 2 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&varApplNo=003977

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Werner, A. A. (1932). "Effect of Theelin Injections upon the Castrated Woman". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 29 (9): 1142–1143. ISSN 1535-3702. doi:10.3181/00379727-29-6259.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Werner, August A.; Collier, W. D. (1933). "Production of Endometrial Growth in Castrated Women". Journal of the American Medical Association. 101 (19): 1466. ISSN 0002-9955. doi:10.1001/jama.1933.02740440026008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Werner, August A. (1937). "Effective Clinical Dosages of Theelin in Oil". Journal of the American Medical Association. 109 (13): 1027. ISSN 0002-9955. doi:10.1001/jama.1937.02780390029011.

- 1 2 3 Escande A, Pillon A, Servant N, Cravedi JP, Larrea F, Muhn P, Nicolas JC, Cavaillès V, Balaguer P (2006). "Evaluation of ligand selectivity using reporter cell lines stably expressing estrogen receptor alpha or beta". Biochem. Pharmacol. 71 (10): 1459–69. PMID 16554039. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.002.

- ↑ Häggström, Mikael; Richfield, David (2014). "Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). ISSN 2002-4436. doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.005.

- ↑ H.J. Buchsbaum (6 December 2012). The Menopause. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-1-4612-5525-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Fluhmann CF (1938). "Estrogenic Hormones: Their Clinical Usage". Cal West Med. 49 (5): 362–6. PMC 1659459

. PMID 18744783.

. PMID 18744783. - 1 2 "Material Safety Data Sheet Estrone" (PDF). ScienceLab.com. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ↑ "Estrone -PubChem". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- 1 2 3 Vern L. Bullough (19 May 1995). Science In The Bedroom: A History Of Sex Research. Basic Books. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-0-465-07259-0.

When Allen and Doisy heard about the [Ascheim-Zondek test for the diagnosis of pregnancy], they realized there was a rich and easily handled source of hormones in urine from which they could develop a potent extract. [...] Allen and and Doisy's research was sponsored by the committee, while that of their main rival, Adolt Butenandt (b. 1903) of the University of Gottingen was sponsored by a German pharmaceutical firm. In 1929, both terms announced the isolation of a pure crystal female sex hormone, estrone, in 1929, although Doisy and Allen did so two months earlier than Butenandt.27 By 1931, estrone was being commercially produced by Parke Davis in this country, and Schering-Kahlbaum in Germany. Interestingly, when Butenandt (who shared the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1939) isolated estrone and analyzed its structure, he found that it was a steroid, the first hormone to be classed in this molecular family.

- ↑ Ulrich Nielsch; Ulrike Fuhrmann; Stefan Jaroch (30 March 2016). New Approaches to Drug Discovery. Springer. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-3-319-28914-4.

The first steroid hormone was isolated from the urine of pregnant women by Adolf Butenandt in 1929 (estrone; see Fig. 1) (Butenandt 1931).

- 1 2 3 Fritz F. Parl (2000). Estrogens, Estrogen Receptor and Breast Cancer. IOS Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-9673355-4-4.

[Doisy] focused his research on the isolation of female sex hormones from hundreds of gallons of human pregnancy urine based on the discovery by Ascheim and Zondeck in 1927 that the urine of pregnant women possessed estrogenic activity [9]. In the summer of 1929, Doisy succeeded in the isolated of estrone (named by him theelin), simultaneously with but independent of Adolf Butenandt of the University of Gottingen in Germany. Doisy presented his results on the crystallization of estrone at the XIII International Physiological Congress in Boston in August 1929 [10].

- 1 2 3 4 James K. Laylin (30 October 1993). Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, 1901-1992. Chemical Heritage Foundation. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-8412-2690-6.

Adolt Friedrich Johann Butenandt was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1939 "for his work on sex hormones"; [...] In 1929 Butenandt isolated estrone [...] in pure crystalline form. [...] Both Butenandt and Edward Doisy isolated estrone simultaneously but independently in 1929. [...] Butenandt took a big step forward in the history of biochemistry when he isolated estrone from the urine of pregnant women. [...] He named it "progynon" in his first publication, and then "folliculine", [...] By 1932, [...] he could determine its chemical structure, [...]

- 1 2 Arthur Greenberg (14 May 2014). Chemistry: Decade by Decade. Infobase Publishing. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-1-4381-0978-7.

Rational chemical studies of human sex hormones began in 1929 with Adolph Butenandt's isolation of pure crystalline estrone, the follicular hormone, from the urine of pregnant women. [...] Butenandt and Ruzicka shared the 1939 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

- ↑ A. Labhart (6 December 2012). Clinical Endocrinology: Theory and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 511–. ISBN 978-3-642-96158-8.

E. A. Doisy and A. Butenandt reported almost at the same time on the isolation of an estrogen-active substance in crystalline form from the urine of pregnant women. N. K. Adam suggested that this substance be named estrone because of the C-17-ketone group present (1933).

- ↑ Thom Rooke (1 January 2012). The Quest for Cortisone. MSU Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-1-60917-326-5.

In 1929 the first estrogen, a steroid called "estrone," was isolated and purified by Doisy; he later won a Nobel Prize for this work.

- ↑ D. Lynn Loriaux (23 February 2016). A Biographical History of Endocrinology. Wiley. pp. 345–. ISBN 978-1-119-20247-9.

- ↑ Campbell, A. D. (1933). "Concerning Placental Hormones and Menstrual Disorders". Annals of Internal Medicine. 7 (3): 330. ISSN 0003-4819. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-7-3-330.

- ↑ Marc A. Fritz; Leon Speroff (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 750–. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

In 1926, Sir Alan S. Parkes and C.W Bellerby coined the basic word "estrin" to designate the hormone or hormones that induce estrus in animals, the time when female mammals are fertile and receptive to males. [...] The terminology was extended to include the prinicipal estrogens in humans, estrone, estradiol, and estriol, in 1932 at the first meeting of the International Conference on the Standardization of Sex Hormones in London, [...]

- 1 2 Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens I: Physiology and Mechanisms of Action of Estrogens and Antiestrogens. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-3-642-58616-3.

The structure of the estrogenic hormones was stated by Butenandt, Thayer, Marrian, and Hazlewood in 1930 and 1931 (see Butenandt 1980). Following the proposition of the Marrian group, the estrogenic hormones were given the trivial names of estradiol, estrone, and estriol. At the first meeting of the International Conference on the Standardization of Sex Hormones, in London (1932), a standard preparation of estrone was established. [...] The partial synthesis of estradiol and estrone from cholesterol and dehydroepiandrosterone was accomplished by Inhoffen and Howleg (Berlin 1940); the total synthesis was achieved by Anner and Miescher (Basel, 1948).

- 1 2 Biskind, Morton S. (1935). "COMMERCIAL GLANDULAR PRODUCTS". Journal of the American Medical Association. 105 (9): 667. ISSN 0002-9955. doi:10.1001/jama.1935.92760350007009a.

- 1 2 3 Elizabeth Siegel Watkins (6 March 2007). The Estrogen Elixir: A History of Hormone Replacement Therapy in America. JHU Press. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-0-8018-8602-7.

- ↑ Gregory Pincus; Thimann Kenneth Vivian Pincus Gregory (2 December 2012). The Hormones V1: Physiology, Chemistry and Applications. Elsevier. pp. 360–. ISBN 978-0-323-14206-9.

- 1 2 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 899–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- 1 2 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 407–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- 1 2 https://www.drugs.com/international/estrone.html