Isfahan

| Isfahan اصفهان | ||

|---|---|---|

| city | ||

| Ancient names: Spahān, Aspadana | ||

| Persian transcription(s) | ||

| ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): Nesf-e Jahān (Half of the world) | ||

Isfahan | ||

Isfahan Isfahan in Iran | ||

| Coordinates: 32°38′N 51°39′E / 32.633°N 51.650°ECoordinates: 32°38′N 51°39′E / 32.633°N 51.650°E | ||

| Country | Iran | |

| Province | Isfahan | |

| County | Isfahan | |

| District | Central | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Mehdi Jamalinejad | |

| • City Council | Chairperson Reza Amini | |

| Area[1] | ||

| • Urban | 493.82 km2 (190.66 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 1,574 m (5,217 ft) | |

| Population (2016 census) | ||

| • city | 1,961,260 | |

| • Population Rank in Iran | 3rd | |

| Population Data from 2016 Census[2] | ||

| Time zone | IRST (UTC+3:30) | |

| • Summer (DST) | IRDT 21 March – 20 September (UTC+4:30) | |

| Area code(s) | 031 | |

| Website | www.isfahan.ir | |

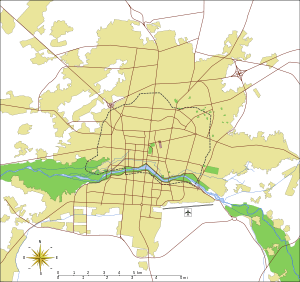

Isfahan (Persian: اصفهان, translit. Esfahān: pronounced ![]() esfæˈhɒːn ), historically also rendered in English as Ispahan, Sepahan, Esfahan or Hispahan, is the capital of Isfahan Province in Iran, located about 340 kilometres (211 miles) south of Tehran.

esfæˈhɒːn ), historically also rendered in English as Ispahan, Sepahan, Esfahan or Hispahan, is the capital of Isfahan Province in Iran, located about 340 kilometres (211 miles) south of Tehran.

The Greater Isfahan Region had a population of 3,793,104 in the 2011 Census, the second most populous metropolitan area in Iran after Tehran. The counties of Isfahan, Borkhar, Najafabad, Khomeynishahr, Shahinshahr, Mobarakeh, Falavarjan, Tiran o Karvan, Lenjan and Jay[3] all constitute the metropolitan city of Isfahan.

Isfahan is located on the main north–south and east–west routes crossing Iran, and was once one of the largest cities in the world. It flourished from 1050 to 1722, particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries under the Safavid dynasty, when it became the capital of Persia for the second time in its history. Even today, the city retains much of its past glory. It is famous for its Persian–Islamic architecture, with many beautiful boulevards, covered bridges, palaces, mosques, and minarets. This led to the Persian proverb "Esfahān nesf-e- jahān ast" (Isfahan is half of the world).[4]

The Naghsh-e Jahan Square in Isfahan is one of the largest city squares in the world. It has been designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. The city also has a wide variety of historic monuments and is known for the paintings, history and architecture.

Isfahan City Center is also the 5th largest shopping mall in the world and combines traditional Isfahani and modern architecture.

History

Name

- See also: Names of Isfahan

The name of the region derives from Middle Persian Spahān. Spahān is attested in various Middle Persian seals and inscriptions, including that of Zoroastrian Magi Kartir,[5] and is also the Armenian name of the city (Սպահան). The present-day name is the Arabicized form of Ispahan (unlike Middle Persian, and similar to Spanish, New Persian does not allow initial consonant clusters such as sp[6]). The region appears with the abbreviation GD (Southern Media) on Sasanian numismatics. In Ptolemy's Geographia it appears as Aspadana, translating to "place of gathering for the army". It is believed that Spahān derives from spādānām 'the armies', Old Persian plural of spāda (from which derives spāh 'army' and spahi (soldier - lit. of the army) in Middle Persian).

Prehistory

The history of Isfahan can be traced back to the Palaeolithic period. In recent discoveries, archaeologists have found artifacts dating back to the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze and Iron ages.

Zoroastrian era

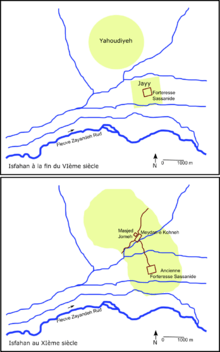

What was to become the city of Isfahan in later historical periods probably emerged as a locality and settlement that gradually developed over the course of the Elamite civilization (2700–1600 BCE).

During the Median dynasty, this commercial entrepôt began to show signs of a more sedentary urbanism, steadily growing into a noteworthy regional centre that benefited from the exceptionally fertile soil on the banks of the Zayandehrud River in a region called Aspandana or Ispandana.

Once Cyrus the Great (reg. 559–529 BCE) unified Persian and Median lands into the Achaemenid Empire (648–330 BCE), the religiously and ethnically diverse city of Isfahan became an early example of the king's fabled religious tolerance. It is said that after Cyrus the Great freed the Jews from Babylon some Jews returned to Jerusalem whereas some others decided to live in Persia and settle in what is now known as Isfahan. But, actually this happened later in the Sasanid period when a Jewish colony was made in the vicinity of the Sasanid.[7]

The tenth century Persian historian Ibn al-Faqih al-Hamedani wrote:

"When the Jews emigrated from Jerusalem, fleeing from Nebuchadnezzar, they carried with them a sample of the water and soil of Jerusalem. They did not settle down anywhere or in any city without examining the water and the soil of each place. They did all along until they reached the city of Isfahan. There they rested, examined the water and soil and found that both resembled Jerusalem. Upon they settled there, cultivated the soil, raised children and grandchildren, and today the name of this settlement is Yahudia."[8]

The Parthians (250 BCE – 226 CE) continued the tradition of tolerance after the fall of the Achaemenids, fostering the Hellenistic dimension within Iranian culture and political organization introduced by Alexander the Great's invading armies. Under the Parthians, Arsacid governors administered a large province from Isfahan, and the city's urban development accelerated to accommodate the needs of a capital city.

The next empire to rule Persia, the Sassanids (226 – 652 CE), presided over massive changes in their realm, instituting sweeping agricultural reform and reviving Iranian culture and the Zoroastrian religion. The city was then called by the name and the region by the name Aspahan or Spahan. The city was governed by "Espoohrans" or the members of seven noble Iranian families who had important royal positions, and served as the residence of these noble families as well. Extant foundations of some Sassanid-era bridges in Isfahan suggest that the kings were also fond of ambitious urban planning projects. While Isfahan's political importance declined during the period, many Sasanian princes would study statecraft in the city, and its military role developed rapidly. Its strategic location at the intersection of the ancient roads to Susa and Persepolis made it an ideal candidate to house a standing army, ready to march against Constantinople at any moment. The words 'Aspahan' and 'Spahan' are derived from the Pahlavi or Middle Persian meaning 'the place of the army'.[9] Although many theories have been mentioned about the origin of Isfahan, in fact little is known of Isfahan before the rule of the Sasanian dynasty (c. 224–c. 651 CE). The historical facts suggest that in the late 4th and early 5th centuries Queen Shushandukht, the Jewish consort of Yazdegerd I (reigned 399–420) settled a colony of Jews in Yahudiyyeh (also spelled Yahudiya), a settlement 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) northwest of the Zoroastrian city of (the Achaemid and Parthian 'Gabae' or 'Gabai', the Sasanid 'Gay' and the Arabicized form 'Jay') that was located just on the northern bank of the Zayanderud River. The gradual population decrease of Gay or Jay and the simultaneous population increase of Yahudiyyeh and its suburbs after the Islamic conquest of Iran resulted in the formation of the nucleus of what was to become the city of Isfahan. It should be noted that the words Aspadana, Ispadana, Spahan and Sepahan from which the word Isfahan is derived all referred to the region in which the city was located.

Islamic era

When the Arabs captured Isfahan in 642, they made it the capital of al-Jibal ("the Mountains") province, an area that covered much of ancient Media. Isfahan grew prosperous under the Persian Buyid (Buwayhid) dynasty, which rose to power and ruled much of Iran when the temporal authority of the Abbasid caliphs waned in the 10th century. The Turkish conqueror and founder of the Seljuq dynasty, Toghril Beg, made Isfahan the capital of his domains in the mid-11th century; but it was under his grandson Malik-Shah I (r. 1073–92) that the city grew in size and splendour.[10]

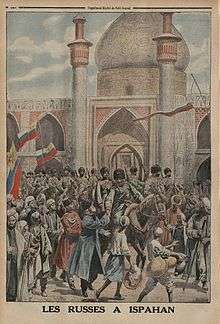

After the fall of the Seljuqs (c. 1200), Isfahan temporarily declined and was eclipsed by other Iranian cities such as Tabriz and Qazvin, but it regained its important position during the Safavid period (1501–1736). The city's golden age began in 1598 when the Safavid ruler Shah Abbas I (reigned 1588–1629) made it his capital and rebuilt it into one of the largest and most beautiful cities of the 17th century. In 1598 Shah Abbas the Great moved his capital from Qazvin to the more central and Persian Isfahan, called Ispahān in early New Persian, so that it wouldn't be threatened by his archrival, the Ottomans. This new importance ushered in a golden age for the city, with architecture, prestige, and Persian culture flourishing. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the city was also settled by thousands of deportees and migrants from the Caucasus that Abbas I and other Safavid rulers had settled en masse in Persia's heartland. Therefore, many of the city’s inhabitants were of Georgian, Circassian, and Daghistani descent.[11] Engelbert Kaempfer, who was in Safavid Persia in 1684-85, estimated their number at 20,000.[11][12] During the Safavid era, the city would form a very large Armenian community as well. As part of Abbas' forced resettlement of peoples from within his empire, he resettled many hundreds of thousands of Armenians (up to 300,000[13][14]) from near the unstable Safavid-Ottoman border, and primarily from the very wealthy Armenian town of Jugha (also known as Old Julfa), in mainland Iran.[14] In Isfahan, he ordered the foundation of a new quarter for the resettled Armenians, primarily meant for the Armenians from Old Julfa, and thus the Armenian Quarter of Isfahan was named New Julfa.[13][14] Today, the New Jolfa district of Isfahan remains a heavily Armenian-populated district, with Armenian Churches and shops, the Vank Cathedral being especially notable for its combination of Armenian Christian and Iranian Islamic elements. It is still one of the oldest and largest Armenian quarters in the world. Following an agreement between Shah Abbas I and his Georgian subject Teimuraz I of Kakheti ("Tahmuras Khan"), whereby the latter submitted to Safavid rule in exchange for being allowed to rule as the region’s wāli (governor) and for having his son serve as dāruḡa ("prefect") of Isfahan in perpetuity, the Georgian prince converted to Islam and served as governor.[11] He was accompanied by a certain number of soldiers, and they spoke in Georgian among themselves.[11] Some were also Georgian Orthodox Christians.[11] The royal court in Isfahan had a great number of Georgian ḡolāms (military slaves) as well as Georgian women.[11] Although they spoke Persian or Turkic, their mother tongue was Georgian.[11] During the time of Abbas and on Isfahan was very famous in Europe, and many European travellers made an account of their visit to the city, such as Jean Chardin. This all lasted until it was sacked by Afghan invaders in 1722 during the Safavids heavy decline.

Isfahan declined once more, and the capital was subsequently moved to Mashhad and Shiraz during the Afsharid and Zand periods respectively until it was finally settled in Tehran in 1775 by Agha Mohammad Khan the founder of the Qajar dynasty.

In the 20th century Isfahan was resettled by a very large number of people from southern Iran, firstly during the population migrations in the early century, and again in the 1980s following the Iran-Iraq war.

Modern age

Today Isfahan, the third largest city in Iran, produces fine carpets, textiles, steel, handicrafts, specific sweet and traditional delicious foods. Isfahan also has nuclear experimental reactors as well as facilities for producing nuclear fuel (UCF). Isfahan has one of the largest steel-producing facilities in the entire region, as well as facilities for producing special alloys. Mobarakeh Steel Company is the biggest steel producer in Middle East and Northern Africa and the biggest DRI producer in the world[15] and Isfahan Steel Company is the first and largest manufacturer of constructional steel products in Iran.[16]

The city has an international airport and is in the final stages of constructing its first Metro line.

Isfahan contains a major oil refinery and a large airforce base. HESA, Iran's most advanced aircraft manufacturing plant (where the IrAn-140Ukrainian-Iranian aircraft is made), is located nearby.[17][18] Isfahan is also becoming an attraction for international investments,[19] like investments in Isfahan City Center.[20]

Isfahan hosted the International Physics Olympiad in 2007.

Geography and climate

The city is located in the lush plain of the Zayanderud River, at the foothills of the Zagros mountain range. The nearest mountain is Mount Soffeh (Kuh-e Soffeh) which is situated just south of Isfahan. No geological obstacles exist within 90 kilometres (56 miles) north of Isfahan, allowing cool northern winds to blow from this direction. Situated at 1,590 metres (5,217 ft) above sea level on the eastern side of the Zagros Mountains, Isfahan has an arid climate (Köppen BWk). Despite its altitude, Isfahan remains hot during the summer with maxima typically around 35 °C (95 °F). However, with low humidity and moderate temperatures at night, the climate can be very pleasant. During the winter, days are mild while nights can be very cold. Snow has occurred at least once every winter except 1986/1987 and 1989/1990.[21]

| Climate data for Isfahan (1961–1990, extremes 1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

32.0 (89.6) |

37.6 (99.7) |

41.0 (105.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

42.0 (107.6) |

39.0 (102.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

26.8 (80.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.4 (50.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

21.3 (70.3) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.4 (84.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.5 (40.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −19.4 (−2.9) |

−12.2 (10) |

−8 (18) |

−4 (25) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.0 (50) |

13.0 (55.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.0 (41) |

0.0 (32) |

−8 (18) |

−13 (9) |

−19.4 (−2.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 17.1 (0.673) |

14.1 (0.555) |

18.2 (0.717) |

19.2 (0.756) |

8.8 (0.346) |

0.6 (0.024) |

0.7 (0.028) |

0.2 (0.008) |

0.0 (0) |

4.1 (0.161) |

9.9 (0.39) |

19.6 (0.772) |

112.5 (4.429) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 4.0 | 2.9 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 23.5 |

| Average snowy days | 3.2 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.9 | 7.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60 | 51 | 43 | 39 | 33 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 36 | 48 | 57 | 39 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 205.3 | 213.3 | 242.1 | 244.5 | 301.3 | 345.4 | 347.6 | 331.2 | 311.6 | 276.5 | 226.1 | 207.6 | 3,252.5 |

| Source #1: NOAA[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Iran Meteorological Organization (records)[23][24] | |||||||||||||

| Esfahan, Iran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main sights

The city core consists of an older section, revolving around the Jameh Mosque, and the Safavid expansion around Naqsh-e Jahan Square, with the surrounding worship places, palaces, and bazaars.[26]

Bazaars

- Shahi Bazaar – 17th century

- Qeysarie Bazaar - 17th century

Bridges

The Zayande River starts in the Zagros Mountains, flows from west to east through the heart of Isfahan, and dries up in the Gavkhooni wetland.

The bridges over the river include some of the finest architecture in Isfahan. The oldest bridge is the Shahrestan bridge, whose foundations was built by the Sasanian Empire (3rd-7th century Sassanid era) and has been repaired during the Seljuk period. Further upstream is Khaju bridge, which was built by Shah Abbas II in 1650. It is 123 metres (404 feet) long with 24 arches, and also serves as a sluice gate.

The next bridge is Choobi (Joui) bridge. It was originally built as an aqueduct to supply the palace gardens on the north bank of the river. Further upstream again is the Si-o-Seh Pol or bridge of 33 arches. Built during the rule of Shah Abbas the Great, it linked Isfahan with the Armenian suburb of New Julfa. It is by far the longest bridge in Isfahan at 295 m (967.85 ft).

Other bridges include Marnan Bridge.

Churches and cathedrals

- Bedkhem Church – 1627

- St. Georg Church – 17th century

- St. Jakob Church _ 1607

- St. Mary Church – 17th century

- Vank Cathedral – 1664

Emamzadehs

- Emamzadeh Ahmad

- Emamzadeh Esmaeil, Isfahan

- Emamzadeh Haroun-e-Velayat – 16th century

- Emamzadeh Jafar

- Emamzadeh Shah Zeyd

Gardens and parks

Houses

- Alam's House

- Amin's House

- Malek Vineyard

- Qazvinis' House – 19th century

- Sheykh ol-Eslam's House

Mausoleums and tombs

- Al-Rashid Mausoleum – 12th century

- Baba Ghassem Mausoleum – 14th century

- Mausoleum of Safavid Princes

- Nizam al-Mulk Tomb – 11th century

- Saeb Mausoleum

- Shahshahan mausoleum – 15th century

- Soltan Bakht Agha Mausoleum – 14th century

Minarets

- Ali minaret – 11th century

- Bagh-e-Ghoushkhane minaret – 14th century

- Chehel Dokhtaran minaret – 12 century

- Dardasht minarets – 14th century

- Darozziafe minarets – 14th century

- Menar Jonban – 14th century

- Sarban minaret

Mosques

- Agha Nour mosque – 16th century

- Hakim Mosque

- Ilchi mosque

- Jameh Mosque[27]

- Jarchi mosque – 1610

- Lonban mosque

- Maghsoudbeyk mosque – 1601

- Mohammad Jafar Abadei mosque – 1878

- Rahim Khan mosque – 19th century

- Roknolmolk mosque

- Seyyed mosque – 19th century

- Shah Mosque – 1629

- Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque – 1618

Museums

- Contemporary Arts Museum Isfahan

- Isfahan City Center Museum

- Museum of Decorative Arts

- Natural History Museum of Isfahan – 15th century

Schools (madresse)

- Chahar Bagh School – early 17th century

- Harati

- Kassegaran school – 1694

- Madreseye Khajoo

- Nimavar school – 1691

- Sadr school – 19th century

Palaces and caravanserais

- Ali Qapu (The Royal Palace) – early 17th century

- Chehel Sotoun (The Palace of Forty Columns) – 1647

- Hasht-Behesht (The Palace of Eight Paradises) – 1669

- Shah Caravanserai

- Talar Ashraf (The Palace of Ashraf) – 1650

Squares and streets

- Chaharbagh Boulevard – 1596

- Chaharbagh-e-khajou Boulevard

- Meydan Kohne (Old Square)

- Naqsh-e Jahan Square also known as "Shah Square" or "Imam Square" – 1602

Synagogues

- Kenisa-ye Bozorg (Mirakhor's kenisa)

- Kenisa-ye Molla Rabbi

- Kenisa-ye Sang-bast

- Mullah Jacob Synagogue

- Mullah Neissan Synagogue

- Kenisa-ye Keter David

Tourist attractions

The central historical area in Isfahan is called Seeosepol (the name of a famous bridge).[28][29]

Other sites

- Atashgah – a Zoroastrian fire temple

- The Bathhouse of Bahāʾ al-dīn al-ʿĀmilī

- Isfahan City Center

- Jarchi hammam

- New Julfa (The Armenian Quarter) – 1606

- Pigeon Towers[30] – 17th century

- Takht-e Foulad

Education

Aside from the seminaries and religious schools, the major universities of the Esfahan metropolitan area are:

- Universities

- High schools

- Adab Highl School

- Farzanegan e Amin High School

- Harati High School

- Imam Mohammad Bagher Education Complex

- Imam Sadegh Education Complex

- Mahboobeh Danesh (Navaie)

- Pooya High School

- Saadi High School

- Sa'eb Education Complex

- Salamat High School

- Saremiyh High School

- Shahid Ejei High School

There are also more than 50 technical and vocational training centers under the administration of Esfahan TVTO which provide non-formal training programs freely throughout the province.[31]

Transportation

Road transport

Isfahan's internal highway network is currently under heavy expansion which began during the last decade. Its lengthy construction is due to concerns of possible destruction of valuable historical buildings. Outside the city, Isfahan is connected by modern highways to Tehran which spans a distance of nearly 400 km (248.55 mi) to North and to Shiraz at about 200 km (124.27 mi) to the south. The highways also service satellite cities surrounding the metropolitan area.[32]

Culture

.jpg)

Notable people

- Music

- Jalal Taj Eesfahani (1903-1981), musician, singer and vocalist[33]

- Hassan Kassai (1928-2012), musician[34]

- Alireza Eftekhari (1956– ), singer[35]

- Leila Forouhar, pop singer[36]

- Jalil Shahnaz (1921-2013), soloist of tar, a traditional Persian instrument[37]

- Hassan Shamaizadeh, songwriter and singer

- Hesameddin Seraj, musician, singer and vocalist[38]

- Film

- Rasul Sadr Ameli (1953–), director

- Reza Arhamsadr (1924–2008), actor

- Homayoun Ershadi (1947–), Hollywood actor and architect

- Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari (1956–2001), former princess of Iran and actress

- Asghar Farhadi (1972– ), Oscar-winning director[39]

- Bahman Farmanara (1942–), director

- Jahangir Forouhar (1916–1997), actor and father of Leila Forouhar (Iranian singer)

- Mohamad Ali Keshvarz (1930-), actor

- Kiumars Poorahmad (1949–), director

- Soroush Sehat (1965–), actor and director[40]

- Craftsmen and Painters

- Mahmoud Farshchian (1930–), painter and miniaturist[41]

- Reza Badrossama (1949–), painter and miniaturist[42]

- Freydoon Rassouli (1943–), American painter born and raised in Isfahan[43]

- Bogdan Saltanov (1630s–1703), Russian icon painter of Isfahanian Armenian origin

- Mahmoud Dehnavi (1927–), craftsman and artist[44]

- Political figures

- Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti (1928–1981), cleric, Chairman of the Council of Revolution of Iran

- Mohammad-Ali Foroughi, a politician and Prime Minister of Iran in the World War II era

- Hossein Fatemi, PhD (1919–1954), politician; foreign minister in Mohamed Mossadegh's cabinet

- Ahmad Amir-Ahmadi (1906–1965), military leader and cabinet minister

- Hossein Kharrazi, chief of the army in the Iran–Iraq war

- Mohsen Nourbakhsh (1948–2003), economist, Governor of the Central Bank of Iran

- Nusrat Bhutto, Chairman of Pakistan Peoples Party from 1979–1983; wife of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto; mother of Benazir Bhutto

- Dariush Forouhar (August 1928 – November 1998), a founder and leader of the Hezb-e Mellat-e Iran (Nation of Iran Party)

- Mohammad Javad Zarif (January 1960 –), Minister of Foreign Affairs and former Ambassador of Iran to the United Nations

- Religious figures

- Lady Amin (Banou Amin) (1886–1983), Iran's most outstanding female jurisprudent, theologian and great Muslim mystic (‘arif), a Lady Mujtahideh

- Amina Begum Bint al-Majlisi was a female Safavid mujtahideh

- Allamah al-Majlisi (1616–1698), Safavid cleric, Sheikh ul-Islam in Isfahan

- Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti (1928–1981), cleric, Chairman of the Council of Revolution of Iran

- Abu Nu'aym Al-Ahbahani Al-Shafi'i (d. 1038 / AH 430), Sunni Shafi'i Scholar

- Salman the Persian

- Abū Shujāʿ al-Iṣfahānī

- Sportspeople

- Abdolali Changiz, football star of Esteghlal FC in the 1970s

- Mansour Ebrahimzadeh, former player for Sepahan FC, former head coach of Zobahan

- Ghasem Haddadifar, captain of Zobahan

- Ehsan Hajsafi, player for the Sepahan and FSV Frankfurt

- Arsalan Kazemi, forward for the Oregon Ducks men's basketball team and the Iran national basketball team

- Rasoul Korbekandi, goalkeeper of the Iranian National Team

- Moharram Navidkia, captain of Sepahan

- Mohsen Sadeghzadeh, former captain of Iran national basketball team and Zobahan

- Mohammad Talaei, world champion wrestler

- Mahmoud Yavari (1939-), former football player, and later coach for Iranian National Team

- Writers and poets

- Mohammad-Ali Jamālzādeh Esfahani (1892–1997), author

- Hatef Esfehani, Persian Moral poet in the Afsharid Era

- Kamal ed-Din Esmail (late 12th century - early 13th century)

- Houshang Golshiri (1938–2000), writer and editor

- Hamid Mosadegh (1939–1998), poet and lawyer

- Mirza Abbas Khan Sheida (1880–1949), poet and publisher

- Saib Tabrizi

- Others

- Abd al-Ghaffar Amilakhori, 17th-century noble

- Adib Boroumand (1924-) poet, politician, lawyer, and leader of the National Front

- Jesse of Kakheti, king of Kakheti in eastern Georgia from 1614 to 1615

- Simon II of Kartli, king of Kartli in eastern Georgia from 1619 to 1630/1631

- David II of Kakheti, king of Kakheti in eastern Georgia from 1709 to 1722

- Constantine II of Kakheti, king of Kakheti in eastern Georgia from 1722 to 1732

- George Bournoutian, professor, historian and author

- Nasser David Khalili (1945–), property developer, art collector, and philanthropist

- Arthur Pope (1881–1969), American archaeologist, buried near Khaju Bridge

Sports

Both Zob Ahan and Sepahan are the only Iranian clubs to reach the final of the new AFC Champions League.

Isfahan has three association football clubs that play professionally. These are:

Giti Pasand also has a futsal team, Giti Pasand FSC, one of the best teams in Asia and Iran. They won the AFC Futsal Club Championship in 2012 and were runners-up in 2013.

Twin towns – sister cities

Isfahan is twinned with:

| Country | City | State / Province / Region / Governorate | Since | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Xi'an | Shaanxi Province | 1989[45] | |

| Malaysia | Kuala Lampur | Kuala Lumpur | 1997[45] | |

| Germany | Freiburg | Baden-Württemberg State | 2000[45] | |

| Italy | Florence | Florence Province | 1998[45] | |

| Romania | Iaşi | Iași County | 1999[45] | |

| Spain | Barcelona | Barcelona Province | 2000[45] | |

| Armenia | Yerevan | Yerevan | 2000[45] | |

| Kuwait | Kuwait City | Al Asimah Governorate | 2000[45] | |

| Cuba | Havana | La Habana Province | 2001[45] | |

| Pakistan | Lahore | Punjab Province | 2004[45] | |

| Russia | Saint Petersburg | Northwestern Federal District | 2004[45] | |

| Senegal | Dakar | Dakar Region | 2009[45] | |

| Lebanon | Baalbek | Baalbek-Hermel Governorate | 2010[45] | |

| South Korea | Gyeongju | North Gyeongsang Province | 2017[46] | |

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ http://www.daftlogic.com/downloads/kml/10102015-9mzrdauu.kml

- ↑ "تعداد جمعیت و خانوار به تفکیک تقسیمات کشوری براساس سرشماری عمومی نفوس و مسکن سال ۱۳۹۵". Statistical Center of Iran.

- ↑ "Maziar Dehghan".

- ↑ "Isfahan Is Half The World", Saudi Aramco World, Volume 13, Nr. 1, January 1962

- ↑ "Isfahan, Pre-Islamic-Period". Encyclopædia Iranica. 15 December 2006. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ↑ Strazny, P. (2005). Encyclopedia of linguistics (p. 325). New York: Fitzroy Dearborn.

- ↑ Historical Geography, Isfahan, http://www.iranicaonline.org//

- ↑ Sacred Precincts: The Religious Architecture of Non-Muslim Communities Across the Islamic World, Gharipour Mohammad, BRILL, Nov 14, 2014 page 179.

- ↑ http://archnet.org/library/places/one-place.jsp?place_id=1752&order_by=title&showdescription=1

- ↑ "Britannica.com".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 electricpulp.com. "ISFAHAN vii. SAFAVID PERIOD – Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ↑ Matthee 2012, p. 67.

- 1 2 Aslanian, Sebouh (2011). From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: The Global Trade Networks of Armenian Merchants from New Julfa. California: University of California Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0520947573.

- 1 2 3 Bournoutian, George (2002). A Concise History of the Armenian People: (from Ancient Times to the Present) (2 ed.). Mazda Publishers. p. 208. ISBN 978-1568591414.

- ↑ "MSC at a Glance". Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ "Esfahan Steel Company A Pioneer in The Steel Industry of Iran". Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Hesaco.com (from the HESA official company website)

- ↑ Pike, John. "HESA Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industrial Company".

- ↑ "International conference held on investment opportunities in Iran tourism industry".

- ↑ DEPARTMENT-it@isfahancitycenter.com, IT. "صفحه اصلی بزرگترین مرکز خرید ایران".

- ↑ "Snowy days for Esfahan". Irimo.ir. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ "Esfahan Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Highest record temperature in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Lowest record temperature in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Weather Information for Esfahan". World Weather Information Service.

- ↑ Assari, A., Mahesh, T., Emtehani, M., & Assari, E. (2011). Comparative sustainability of bazaar in Iranian traditional cities: Case studies in Isfahan and Tabriz. International Journal on Technical and Physical Problems of Engineering (IJTPE)(9), 18-24.

- ↑ "Isfahan Jame(Congregative) mosque – BackPack". Fz-az.fotopages.com. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ "Seifolddini-Faranak; M. S. Fard; Hosseini Ali" (PDF). thescipub.com.

- ↑ Assari, Ali; T.M. Mahesh (January 2012). "Conservation of historic urban core in traditional Islamic culture: case study of Isfahan city" (PDF). Indian Journal of Science and Technology. 5 (1): 1970–1976. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ "Castles of the Fields". Saudi Aramco World. Retrieved 2012-09-11.

- ↑ "Isfahan Technical and Vocational Training Organization". Web.archive.org. 8 October 2007. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Assari, Ali; Erfan Assari (2012). "Urban spirit and heritage conservation problems: case study Isfahan city in Iran" (PDF). Journal of American Science. 8 (1): 203–209. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ↑ "نگاهی به زندگی و کارنامه هنری استاد جلال تاج". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "Hassan Kassai". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "بیوگرافی علیرضا افتخاری". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "بیوگرافی لیلا فروهر / عکس · جدید 96 -گهر". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "شهسوار تار". Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "بیوگرافی حسام الدین سراج". Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "بیوگرافی اصغر فرهادی - زومجی". Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "بیوگرافی کامل سروش صحت + عکس". Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "مروري كوتاه بر زندگينامه استاد محمود فرشچيان". Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "Reza Badrossama Biography". Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "Abstract paintings and conceptual spiritual art by Freydoon Rassouli". Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "استاد محمود دهنوی". Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "خواهر خوانده های اصفهان". Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ↑ "گوانجو کره جنوبی پانزدهمین خواهرخوانده اصفهان". 11 March 2017.

- Dehghan, Maziar (2014). Management in IRAN. ISBN 978-600-04-1573-0.

Sources

- Yves Bomati and Houchang Nahavandi,Shah Abbas, Emperor of Persia,1587-1629, 2017, ed. Ketab Corporation, Los Angeles, ISBN 978-1595845672, English translation by Azizeh Azodi.

- Matthee, Rudi (2012). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1845117450.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isfahan. |

![]() Isfahan travel guide from Wikivoyage

Isfahan travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Isfahan official website

- Isfahan Metro

- 360-degree panorama gallery of Isfahan

- Isfahan Geometry on a Human Scale - a documentary film directed by Manouchehr Tayyab (30 min)

| Preceded by Rey |

Capital of Seljuq Empire (Persia) 1051–1118 |

Succeeded by Hamadan (Western capital) Merv (Eastern capital) |

| Preceded by Qazvin |

Capital of Iran (Persia) 1598–1736 |

Succeeded by Mashhad |

| Preceded by Qazvin |

Capital of Safavid dynasty 1598–1722 |

Succeeded by - |