Che Guevara

| Che Guevara | |

|---|---|

|

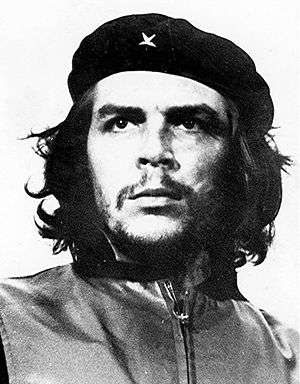

Guerrillero Heroico Picture taken by Alberto Korda on March 5, 1960, at the La Coubre memorial service. | |

| Born |

Ernesto Guevara June 14, 1928[1] Rosario, Santa Fe province, Argentina |

| Died |

October 9, 1967 (aged 39) La Higuera, Vallegrande, Bolivia |

| Cause of death | Execution by shooting |

| Resting place |

Che Guevara Mausoleum Santa Clara, Cuba |

| Alma mater | University of Buenos Aires |

| Occupation | Physician, author, guerrilla, government official |

| Organization | 26th of July Movement, United Party of the Cuban Socialist Revolution,[2] National Liberation Army (Bolivia) |

| Known for | Guevarism |

| Spouse(s) |

Hilda Gadea (1955–1959) Aleida March (1959–1967, his death) |

| Children |

Hilda (1956–1995) Aleida (born 1960) Camilo (born 1962) Celia (born 1963) Ernesto (born 1965) |

| Parent(s) |

Ernesto Guevara Lynch[3] Celia de la Serna y Llosa[3] |

| Signature | |

| |

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈtʃe ɣeˈβaɾa][4] June 14, 1928 – October 9, 1967)[1][5] was an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and military theorist. A major figure of the Cuban Revolution, his stylized visage has become a ubiquitous countercultural symbol of rebellion and global insignia in popular culture.[6]

As a young medical student, Guevara traveled throughout South America and was radicalized by the poverty, hunger, and disease he witnessed.[7] His burgeoning desire to help overturn what he saw as the capitalist exploitation of Latin America by the United States prompted his involvement in Guatemala's social reforms under President Jacobo Árbenz, whose eventual CIA-assisted overthrow at the behest of the United Fruit Company solidified Guevara's political ideology.[7] Later, in Mexico City, he met Raúl and Fidel Castro, joined their 26th of July Movement, and sailed to Cuba aboard the yacht Granma, with the intention of overthrowing U.S.-backed Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista.[8] Guevara soon rose to prominence among the insurgents, was promoted to second-in-command, and played a pivotal role in the victorious two-year guerrilla campaign that deposed the Batista regime.[9]

Following the Cuban Revolution, Guevara performed a number of key roles in the new government. These included reviewing the appeals and firing squads for those convicted as war criminals during the revolutionary tribunals,[10] instituting agrarian land reform as minister of industries, helping spearhead a successful nationwide literacy campaign, serving as both national bank president and instructional director for Cuba's armed forces, and traversing the globe as a diplomat on behalf of Cuban socialism. Such positions also allowed him to play a central role in training the militia forces who repelled the Bay of Pigs Invasion[11] and bringing the Soviet nuclear-armed ballistic missiles to Cuba which precipitated the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.[12] Additionally, he was a prolific writer and diarist, composing a seminal manual on guerrilla warfare, along with a best-selling memoir about his youthful continental motorcycle journey. His experiences and studying of Marxism–Leninism led him to posit that the Third World's underdevelopment and dependence was an intrinsic result of imperialism, neocolonialism, and monopoly capitalism, with the only remedy being proletarian internationalism and world revolution.[13][14] Guevara left Cuba in 1965 to foment revolution abroad, first unsuccessfully in Congo-Kinshasa and later in Bolivia, where he was captured by CIA-assisted Bolivian forces and summarily executed.[15]

Guevara remains both a revered and reviled historical figure, polarized in the collective imagination in a multitude of biographies, memoirs, essays, documentaries, songs, and films. As a result of his perceived martyrdom, poetic invocations for class struggle, and desire to create the consciousness of a "new man" driven by moral rather than material incentives,[16] he has evolved into a quintessential icon of various leftist movements. Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century,[17] while an Alberto Korda photograph of him, titled Guerrillero Heroico (shown), was cited by the Maryland Institute College of Art as "the most famous photograph in the world".[18]

Early life

Ernesto Guevara was born to Ernesto Guevara Lynch and his wife, Celia de la Serna y Llosa, on June 14, 1928,[1] in Rosario, Argentina, the eldest of five children in a middle-class Argentine family of Spanish (including Basque and Cantabrian) descent, as well as Irish by means of his ancestor Patrick Lynch.[19][20][21] In accordance with the flexibility allowed in Spanish naming customs, his legal name (Ernesto Guevara) will sometimes appear with "de la Serna" and/or "Lynch" accompanying it.[22] Referring to Che's "restless" nature, his father declared "the first thing to note is that in my son's veins flowed the blood of the Irish rebels".[23]

Very early on in life, Ernestito (as he was then called) developed an "affinity for the poor".[24] Growing up in a family with leftist leanings, Guevara was introduced to a wide spectrum of political perspectives even as a boy.[25] His father, a staunch supporter of Republicans from the Spanish Civil War, often hosted many veterans from the conflict in the Guevara home.[26]

Despite suffering crippling bouts of acute asthma that were to afflict him throughout his life, he excelled as an athlete, enjoying swimming, football, golf, and shooting, while also becoming an "untiring" cyclist.[27][28] He was an avid rugby union player,[29] and played at fly-half for Club Universitario de Buenos Aires.[30] His rugby playing earned him the nickname "Fuser"—a contraction of El Furibundo (raging) and his mother's surname, de la Serna—for his aggressive style of play.[31]

Intellectual and literary interests

Guevara learned chess from his father and began participating in local tournaments by age 12. During adolescence and throughout his life, he was passionate about poetry, especially that of Pablo Neruda, John Keats, Antonio Machado, Federico García Lorca, Gabriela Mistral, César Vallejo, and Walt Whitman.[32] He could also recite Rudyard Kipling's "If—" and José Hernández's Martín Fierro by heart.[32] The Guevara home contained more than 3,000 books, which allowed Guevara to be an enthusiastic and eclectic reader, with interests including Karl Marx, William Faulkner, André Gide, Emilio Salgari and Jules Verne.[33] Additionally, he enjoyed the works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Franz Kafka, Albert Camus, Vladimir Lenin, and Jean-Paul Sartre; as well as Anatole France, Friedrich Engels, H. G. Wells, and Robert Frost.[34]

As he grew older, he developed an interest in the Latin American writers Horacio Quiroga, Ciro Alegría, Jorge Icaza, Rubén Darío, and Miguel Asturias.[34] Many of these authors' ideas he cataloged in his own handwritten notebooks of concepts, definitions, and philosophies of influential intellectuals. These included composing analytical sketches of Buddha and Aristotle, along with examining Bertrand Russell on love and patriotism, Jack London on society, and Nietzsche on the idea of death. Sigmund Freud's ideas fascinated him as he quoted him on a variety of topics from dreams and libido to narcissism and the Oedipus complex.[34] His favorite subjects in school included philosophy, mathematics, engineering, political science, sociology, history and archaeology.[35][36]

Years later, a February 13, 1958, declassified CIA 'biographical and personality report' would make note of Guevara's wide range of academic interests and intellect, describing him as "quite well read" while adding that "Che is fairly intellectual for a Latino."[37]

Motorcycle journey

In 1948, Guevara entered the University of Buenos Aires to study medicine. His "hunger to explore the world"[38] led him to intersperse his collegiate pursuits with two long introspective journeys that would fundamentally change the way he viewed himself and the contemporary economic conditions in Latin America. The first expedition in 1950 was a 4,500-kilometer (2,800 mi) solo trip through the rural provinces of northern Argentina on a bicycle on which he installed a small engine.[39] This was followed in 1951 by a nine-month, 8,000-kilometer (5,000 mi) continental motorcycle trek through most of South America. For the latter, he took a year off from his studies to embark with his friend Alberto Granado, with the final goal of spending a few weeks volunteering at the San Pablo leper colony in Peru, on the banks of the Amazon River.[40]

In Chile, Guevara found himself enraged by the working conditions of the miners in Anaconda's Chuquicamata copper mine and moved by his overnight encounter in the Atacama Desert with a persecuted communist couple who did not even own a blanket, describing them as "the shivering flesh-and-blood victims of capitalist exploitation".[42] Additionally, on the way to Machu Picchu high in the Andes, he was struck by the crushing poverty of the remote rural areas, where peasant farmers worked small plots of land owned by wealthy landlords.[43] Later on his journey, Guevara was especially impressed by the camaraderie among those living in a leper colony, stating "The highest forms of human solidarity and loyalty arise among such lonely and desperate people."[43] Guevara used notes taken during this trip to write an account, titled The Motorcycle Diaries, which later became a New York Times best-seller,[44] and was adapted into a 2004 award-winning film of the same name.

The journey took Guevara through Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, and Miami, Florida, for 20 days,[45] before returning home to Buenos Aires. By the end of the trip, he came to view Latin America not as collection of separate nations, but as a single entity requiring a continent-wide liberation strategy. His conception of a borderless, united Hispanic America sharing a common Latino heritage was a theme that recurred prominently during his later revolutionary activities. Upon returning to Argentina, he completed his studies and received his medical degree in June 1953, making him officially "Dr. Ernesto Guevara".[46][47]

— George Galloway, British politician[48]

Guevara later remarked that through his travels in Latin America, he came in "close contact with poverty, hunger and disease" along with the "inability to treat a child because of lack of money" and "stupefaction provoked by the continual hunger and punishment" that leads a father to "accept the loss of a son as an unimportant accident". It was these experiences which Guevara cites as convincing him that in order to "help these people", he needed to leave the realm of medicine, and consider the political arena of armed struggle.[7]

Guatemala, Árbenz, and United Fruit

On July 7, 1953, Guevara set out again, this time to Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and El Salvador. On December 10, 1953, before leaving for Guatemala, Guevara sent an update to his Aunt Beatriz from San José, Costa Rica. In the letter Guevara speaks of traversing the dominion of the United Fruit Company; a journey which convinced him that the Company's capitalist system was a terrible one.[49] This affirmed indignation carried the more aggressive tone he adopted in order to frighten his more Conservative relatives, and ends with Guevara swearing on an image of the then recently deceased Joseph Stalin, not to rest until these "octopuses have been vanquished".[50] Later that month, Guevara arrived in Guatemala where President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán headed a democratically elected government that, through land reform and other initiatives, was attempting to end the latifundia system. To accomplish this, President Árbenz had enacted a major land reform program, where all uncultivated portions of large land holdings were to be expropriated and redistributed to landless peasants. The biggest land owner, and one most affected by the reforms, was the United Fruit Company, from which the Árbenz government had already taken more than 225,000 acres (91,000 ha) of uncultivated land.[51] Pleased with the road the nation was heading down, Guevara decided to settle down in Guatemala so as to "perfect himself and accomplish whatever may be necessary in order to become a true revolutionary."[52]

In Guatemala City, Guevara sought out Hilda Gadea Acosta, a Peruvian economist who was well-connected politically as a member of the left-leaning Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana (APRA, American Popular Revolutionary Alliance). She introduced Guevara to a number of high-level officials in the Arbenz government. Guevara then established contact with a group of Cuban exiles linked to Fidel Castro through the July 26, 1953, attack on the Moncada Barracks in Santiago de Cuba. During this period, he acquired his famous nickname, due to his frequent use of the Argentine filler syllable che (a multi-purpose discourse marker, like the syllable "eh" in Canadian English).[53] During his time in Guatemala, Guevara was helped by other Central American exiles, one of whom, Helena Leiva de Holst, provided him with food and lodging,[54] discussed her travels to study Marxism in Russia and China,[55] and to whom, Guevara dedicated a poem, "Invitación al camino".[56]

On May 15, 1954, a shipment of Škoda infantry and light artillery weapons was dispatched from Communist Czechoslovakia for the Arbenz Government and arrived in Puerto Barrios.[57] As a result, the United States government—which since 1953 had been tasked by President Eisenhower to remove Arbenz from power in the multifaceted CIA operation code named PBSUCCESS—responded by saturating Guatemala with anti-Arbenz propaganda through radio and dropped leaflets, and began bombing raids using unmarked airplanes.[58] The United States also sponsored a force of several hundred Guatemalan refugees and mercenaries who were headed by Castillo Armas to help remove the Arbenz government. Though the impact of the U.S. actions on subsequent events is debatable, by late June, Arbenz came to the conclusion that resistance against the "giant of the north" was futile and resigned.[58] This allowed Armas and his CIA-assisted forces to march into Guatemala City and establish a military junta, which would, twelve days later on July 8, elect Armas President.[58] Consequently, the Armas regime then consolidated power by rounding up hundreds of suspected communists and executed hundreds of prisoners, while crushing the previously flourishing labor unions and restoring all of United Fruits previous land holdings.[58]

Guevara himself was eager to fight on behalf of Arbenz and joined an armed militia organized by the Communist Youth for that purpose, but frustrated with the group's inaction, he soon returned to medical duties. Following the coup, he again volunteered to fight, but soon after, Arbenz took refuge in the Mexican Embassy and told his foreign supporters to leave the country. Guevara's repeated calls to resist were noted by supporters of the coup, and he was marked for murder.[59] After Hilda Gadea was arrested, Guevara sought protection inside the Argentine consulate, where he remained until he received a safe-conduct pass some weeks later and made his way to Mexico.[60]

The overthrow of the Arbenz regime and establishment of the right-wing Armas dictatorship cemented Guevara's view of the United States as an imperialist power that would oppose and attempt to destroy any government that sought to redress the socioeconomic inequality endemic to Latin America and other developing countries.[52] In speaking about the coup, Guevara stated:

The last Latin American revolutionary democracy – that of Jacobo Arbenz – failed as a result of the cold premeditated aggression carried out by the United States. Its visible head was the Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, a man who, through a rare coincidence, was also a stockholder and attorney for the United Fruit Company.[59]

Guevara's conviction that Marxism achieved through armed struggle and defended by an armed populace was the only way to rectify such conditions was thus strengthened.[61] Gadea wrote later, "It was Guatemala which finally convinced him of the necessity for armed struggle and for taking the initiative against imperialism. By the time he left, he was sure of this."[62]

Mexico City and preparation

Guevara arrived in Mexico City on 21 September 1954, and worked in the allergy section of the General Hospital and at the Hospital Infantil de Mexico.[63][64] In addition he gave lectures on medicine at the Faculty of Medicine in the National Autonomous University of Mexico and worked as a news photographer for Latina News Agency.[65][66] His first wife Hilda notes in her memoir My Life with Che, that for a while, Guevara considered going to work as a doctor in Africa and that he continued to be deeply troubled by the poverty around him.[67] In one instance, Hilda describes Guevara's obsession with an elderly washerwoman whom he was treating, remarking that he saw her as "representative of the most forgotten and exploited class". Hilda later found a poem that Che had dedicated to the old woman, containing "a promise to fight for a better world, for a better life for all the poor and exploited".[67]

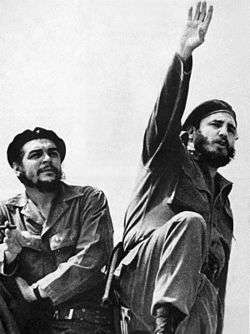

During this time he renewed his friendship with Ñico López and the other Cuban exiles whom he had met in Guatemala. In June 1955, López introduced him to Raúl Castro, who subsequently introduced him to his older brother, Fidel Castro, the revolutionary leader who had formed the 26th of July Movement and was now plotting to overthrow the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. During a long conversation with Fidel on the night of their first meeting, Guevara concluded that the Cuban's cause was the one for which he had been searching and before daybreak he had signed up as a member of the July 26 Movement.[68] Despite their "contrasting personalities", from this point on Che and Fidel began to foster what dual biographer Simon Reid-Henry deems a "revolutionary friendship that would change the world", as a result of their coinciding commitment to anti-imperialism.[69]

By this point in Guevara's life, he deemed that U.S.-controlled conglomerates installed and supported repressive regimes around the world. In this vein, he considered Batista a "U.S. puppet whose strings needed cutting".[70] Although he planned to be the group's combat medic, Guevara participated in the military training with the members of the Movement. The key portion of training involved learning hit and run tactics of guerrilla warfare. Guevara and the others underwent arduous 15-hour marches over mountains, across rivers, and through the dense undergrowth, learning and perfecting the procedures of ambush and quick retreat. From the start Guevara was Alberto Bayo's "prize student" among those in training, scoring the highest on all of the tests given.[71] At the end of the course, he was called "the best guerrilla of them all" by their instructor, General Bayo.[72]

Guevara then married Gadea in Mexico in September 1955, before embarking on his plan to assist in the liberation of Cuba.[73]

Cuban Revolution

Invasion, warfare, and Santa Clara

The first step in Castro's revolutionary plan was an assault on Cuba from Mexico via the Granma, an old, leaky cabin cruiser. They set out for Cuba on November 25, 1956. Attacked by Batista's military soon after landing, many of the 82 men were either killed in the attack or executed upon capture; only 22 found each other afterwards.[74] During this initial bloody confrontation Guevara laid down his medical supplies and picked up a box of ammunition dropped by a fleeing comrade, proving to be a symbolic moment in Che's life.[75]

Only a small band of revolutionaries survived to re-group as a bedraggled fighting force deep in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where they received support from the urban guerrilla network of Frank País, the 26th of July Movement, and local campesinos. With the group withdrawn to the Sierra, the world wondered whether Castro was alive or dead until early 1957 when the interview by Herbert Matthews appeared in The New York Times. The article presented a lasting, almost mythical image for Castro and the guerrillas. Guevara was not present for the interview, but in the coming months he began to realize the importance of the media in their struggle. Meanwhile, as supplies and morale diminished, and with an allergy to mosquito bites which resulted in agonizing walnut-sized cysts on his body,[76] Guevara considered these "the most painful days of the war".[77]

During Guevara's time living hidden among the poor subsistence farmers of the Sierra Maestra mountains, he discovered that there were no schools, no electricity, minimal access to healthcare, and more than 40 percent of the adults were illiterate.[78] As the war continued, Guevara became an integral part of the rebel army and "convinced Castro with competence, diplomacy and patience".[9] Guevara set up factories to make grenades, built ovens to bake bread, taught new recruits about tactics, and organized schools to teach illiterate campesinos to read and write.[9] Moreover, Guevara established health clinics, workshops to teach military tactics, and a newspaper to disseminate information.[79] The man whom Time dubbed three years later "Castro's brain" at this point was promoted by Fidel Castro to Comandante (commander) of a second army column.[9]

As second in command, Guevara was a harsh disciplinarian who sometimes shot defectors. Deserters were punished as traitors, and Guevara was known to send squads to track those seeking to go AWOL.[80] As a result, Guevara became feared for his brutality and ruthlessness.[81] During the guerrilla campaign, Guevara was also responsible for the sometimes summary execution of a number of men accused of being informers, deserters or spies.[82] In his diaries, Guevara described the first such execution of Eutímio Guerra, a peasant army guide who admitted treason when it was discovered he accepted the promise of ten thousand pesos for repeatedly giving away the rebel's position for attack by the Cuban air force.[83] Such information also allowed Batista's army to burn the homes of peasants sympathetic to the revolution.[83] Upon Guerra's request that they "end his life quickly",[83] Che stepped forward and shot him in the head, writing "The situation was uncomfortable for the people and for Eutimio so I ended the problem giving him a shot with a .32 pistol in the right side of the brain, with exit orifice in the right temporal [lobe]."[84] His scientific notations and matter-of-fact description, suggested to one biographer a "remarkable detachment to violence" by that point in the war.[84] Later, Guevara published a literary account of the incident, titled "Death of a Traitor", where he transfigured Eutimio's betrayal and pre-execution request that the revolution "take care of his children", into a "revolutionary parable about redemption through sacrifice".[84]

Although he maintained a demanding and harsh disposition, Guevara also viewed his role of commander as one of a teacher, entertaining his men during breaks between engagements with readings from the likes of Robert Louis Stevenson, Cervantes, and Spanish lyric poets.[85] Together with this role, and inspired by José Martí's principle of "literacy without borders", Guevara further ensured that his rebel fighters made daily time to teach the uneducated campesinos with whom they lived and fought to read and write, in what Guevara termed the "battle against ignorance".[78] Tomás Alba, who fought under Guevara's command, later stated that "Che was loved, in spite of being stern and demanding. We would (have) given our life for him."[86]

His commanding officer Fidel Castro described Guevara as intelligent, daring, and an exemplary leader who "had great moral authority over his troops".[87] Castro further remarked that Guevara took too many risks, even having a "tendency toward foolhardiness".[88] Guevara's teenage lieutenant, Joel Iglesias, recounts such actions in his diary, noting that Guevara's behavior in combat even brought admiration from the enemy. On one occasion Iglesias recounts the time he had been wounded in battle, stating "Che ran out to me, defying the bullets, threw me over his shoulder, and got me out of there. The guards didn't dare fire at him ... later they told me he made a great impression on them when they saw him run out with his pistol stuck in his belt, ignoring the danger, they didn't dare shoot."[89]

Guevara was instrumental in creating the clandestine radio station Radio Rebelde (Rebel Radio) in February 1958, which broadcast news to the Cuban people with statements by the 26th of July movement, and provided radiotelephone communication between the growing number of rebel columns across the island. Guevara had apparently been inspired to create the station by observing the effectiveness of CIA supplied radio in Guatemala in ousting the government of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán.[90]

To quell the rebellion, Cuban government troops began executing rebel prisoners on the spot, and regularly rounded up, tortured, and shot civilians as a tactic of intimidation.[91] By March 1958, the continued atrocities carried out by Batista's forces led the United States to announce it would stop selling arms to the Cuban government.[79] Then in late July 1958, Guevara played a critical role in the Battle of Las Mercedes by using his column to halt a force of 1,500 men called up by Batista's General Cantillo in a plan to encircle and destroy Castro's forces. Years later, Major Larry Bockman of the United States Marine Corps would analyze and describe Che's tactical appreciation of this battle as "brilliant".[92] During this time Guevara also became an "expert" at leading hit-and-run tactics against Batista's army, and then fading back into the countryside before the army could counterattack.[93]

As the war extended, Guevara led a new column of fighters dispatched westward for the final push towards Havana. Travelling by foot, Guevara embarked on a difficult 7-week march only travelling at night to avoid ambush, and often not eating for several days.[94] In the closing days of December 1958, Guevara's task was to cut the island in half by taking Las Villas province. In a matter of days he executed a series of "brilliant tactical victories" that gave him control of all but the province's capital city of Santa Clara.[94] Guevara then directed his "suicide squad" in the attack on Santa Clara, that became the final decisive military victory of the revolution.[95][96] In the six weeks leading up to the Battle of Santa Clara there were times when his men were completely surrounded, outgunned, and overrun. Che's eventual victory despite being outnumbered 10:1, remains in the view of some observers a "remarkable tour de force in modern warfare".[97]

Radio Rebelde broadcast the first reports that Guevara's column had taken Santa Clara on New Year's Eve 1958. This contradicted reports by the heavily controlled national news media, which had at one stage reported Guevara's death during the fighting. At 3 am on January 1, 1959, upon learning that his generals were negotiating a separate peace with Guevara, Fulgencio Batista boarded a plane in Havana and fled for the Dominican Republic, along with an amassed "fortune of more than $300,000,000 through graft and payoffs".[98] The following day on January 2, Guevara entered Havana to take final control of the capital.[99] Fidel Castro took 6 more days to arrive, as he stopped to rally support in several large cities on his way to rolling victoriously into Havana on January 8, 1959. The final death toll from the two years of revolutionary fighting was 2,000 people.[100]

In mid-January 1959, Guevara went to live at a summer villa in Tarará to recover from a violent asthma attack.[101] While there he started the Tarara Group, a group that debated and formed the new plans for Cuba's social, political, and economic development.[102] In addition, Che began to write his book Guerrilla Warfare while resting at Tarara.[102] In February, the revolutionary government proclaimed Guevara "a Cuban citizen by birth" in recognition of his role in the triumph.[103] When Hilda Gadea arrived in Cuba in late January, Guevara told her that he was involved with another woman, and the two agreed on a divorce,[104] which was finalized on May 22.[105] On June 2, 1959, he married Aleida March, a Cuban-born member of the 26th of July movement with whom he had been living since late 1958. Guevara returned to the seaside village of Tarara in June for his honeymoon with Aleida.[106] In total, Guevara would ultimately have five children from his two marriages.[107]

La Cabaña, land reform, and literacy

The first major political crisis arose over what to do with the captured Batista officials who had been responsible for the worst of the repression.[108] During the rebellion against Batista's dictatorship, the general command of the rebel army, led by Fidel Castro, introduced into the territories under its control the 19th century penal law commonly known as the Ley de la Sierra (Law of the Sierra).[109] This law included the death penalty for serious crimes, whether perpetrated by the Batista regime or by supporters of the revolution. In 1959, the revolutionary government extended its application to the whole of the republic and to those it considered war criminals, captured and tried after the revolution. According to the Cuban Ministry of Justice, this latter extension was supported by the majority of the population, and followed the same procedure as those in the Nuremberg trials held by the Allies after World War II.[110]

To implement a portion of this plan, Castro named Guevara commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison, for a five-month tenure (January 2 through June 12, 1959).[111] Guevara was charged with purging the Batista army and consolidating victory by exacting "revolutionary justice" against those considered to be traitors, chivatos (informants) or war criminals.[112] Serving in the post as commander of La Cabaña, Guevara reviewed the appeals of those convicted during the revolutionary tribunal process.[10] The tribunals were conducted by 2–3 army officers, an assessor, and a respected local citizen.[113] On some occasions the penalty delivered by the tribunal was death by firing squad.[114] Raúl Gómez Treto, senior legal advisor to the Cuban Ministry of Justice, has argued that the death penalty was justified in order to prevent citizens themselves from taking justice into their own hands, as happened twenty years earlier in the anti-Machado rebellion.[115] Biographers note that in January 1959, the Cuban public was in a "lynching mood",[116] and point to a survey at the time showing 93% public approval for the tribunal process.[10] Moreover, a January 22, 1959, Universal Newsreel broadcast in the United States and narrated by Ed Herlihy, featured Fidel Castro asking an estimated one million Cubans whether they approved of the executions, and was met with a roaring "¡Si!" (yes).[117] With thousands of Cubans estimated to have been killed at the hands of Batista's collaborators,[118][119] and many of the accused war criminals sentenced to death accused of torture and physical atrocities,[10] the newly empowered government carried out executions, punctuated by cries from the crowds of "¡paredón!" ([to the] wall!),[108] which biographer Jorge Castañeda describes as "without respect for due process".[120]

— Jon Lee Anderson, author of Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, PBS forum[121]

Although there are varying accounts, it is estimated that several hundred people were executed nationwide during this time, with Guevara's jurisdictional death total at La Cabaña ranging from 55 to 105.[122] Conflicting views exist of Guevara's attitude towards the executions at La Cabaña. Some exiled opposition biographers report that he relished the rituals of the firing squad, and organized them with gusto, while others relate that Guevara pardoned as many prisoners as he could.[120] What is acknowledged by all sides is that Guevara had become a "hardened" man, who had no qualms about the death penalty or summary and collective trials. If the only way to "defend the revolution was to execute its enemies, he would not be swayed by humanitarian or political arguments".[120] This is further confirmed by a February 5, 1959, letter to Luis Paredes López in Buenos Aires where Guevara states unequivocally "The executions by firing squads are not only a necessity for the people of Cuba, but also an imposition of the people."[123]

Along with ensuring "revolutionary justice", the other key early platform of Guevara's was establishing agrarian land reform. Almost immediately after the success of the revolution on January 27, 1959, Guevara made one of his most significant speeches where he talked about "the social ideas of the rebel army". During this speech, he declared that the main concern of the new Cuban government was "the social justice that land redistribution brings about".[124] A few months later on May 17, 1959, the Agrarian Reform Law crafted by Guevara went into effect, limiting the size of all farms to 1,000 acres (400 ha). Any holdings over these limits were expropriated by the government and either redistributed to peasants in 67-acre (270,000 m2) parcels or held as state run communes.[125] The law also stipulated that sugar plantations could not be owned by foreigners.[126]

On June 12, 1959, Castro sent Guevara out on a three-month tour of 14 mostly Bandung Pact countries (Morocco, Sudan, Egypt, Syria, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Indonesia, Japan, Yugoslavia, Greece) and the cities of Singapore and Hong Kong.[127] Sending Guevara away from Havana allowed Castro to appear to be distancing himself from Guevara and his Marxist sympathies, which troubled both the United States and some of Castro's July 26 Movement members.[128] While in Jakarta, Guevara visited Indonesian president Sukarno to discuss the recent revolution in Indonesia and to establish trade relations between their two nations. Both men quickly bonded, as Sukarno was attracted to Guevara's energy and his relaxed informal approach; moreover they shared revolutionary leftist aspirations against western imperialism.[129] Guevara next spent 12 days in Japan (July 15–27), participating in negotiations aimed at expanding Cuba's trade relations with that nation. During the visit, he refused to visit and lay a wreath at Japan's Tomb of the Unknown Soldier commemorating soldiers lost during World War II, remarking that the Japanese "imperialists" had "killed millions of Asians".[130] In its place, Guevara stated that he would instead visit Hiroshima, where the American military had detonated an atom-bomb 14 years earlier.[130] Despite his denunciation of Imperial Japan, Guevara also considered President Truman a "macabre clown" for the bombings,[131] and after visiting Hiroshima and its Peace Memorial Museum, he sent back a postcard to Cuba stating, "In order to fight better for peace, one must look at Hiroshima."[132]

Upon Guevara's return to Cuba in September 1959, it was evident that Castro now had more political power. The government had begun land seizures included in the agrarian reform law, but was hedging on compensation offers to landowners, instead offering low interest "bonds", a step which put the United States on alert. At this point the affected wealthy cattlemen of Camagüey mounted a campaign against the land redistributions, and enlisted the newly disaffected rebel leader Huber Matos, who along with the anti-Communist wing of the 26th of July Movement, joined them in denouncing the "Communist encroachment".[133] During this time Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo was offering assistance to the "Anti-Communist Legion of the Caribbean" which was training in the Dominican Republic. This multi-national force, composed mostly of Spaniards and Cubans, but also of Croatians, Germans, Greeks, and right-wing mercenaries, was plotting to topple Castro's new regime.[133]

Such threats were heightened when, on March 4, 1960, two massive explosions ripped through the French freighter La Coubre, which was carrying Belgian munitions from the port of Antwerp, and was docked in Havana Harbor. The blasts killed at least 76 people and injured several hundred, with Guevara personally providing first aid to some of the victims. Cuban leader Fidel Castro immediately accused the CIA of "an act of terrorism" and held a state funeral the following day for the victims of the blast.[134] It was at the memorial service that Alberto Korda took the famous photograph of Guevara, now known as Guerrillero Heroico.[135]

These perceived threats prompted Castro to further eliminate "counter-revolutionaries", and to utilize Guevara to drastically increase the speed of land reform. To implement this plan, a new government agency, the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), was established to administer the new Agrarian Reform law. INRA quickly became the most important governing body in the nation, with Guevara serving as its head in his capacity as minister of industries.[126] Under Guevara's command, INRA established its own 100,000 person militia, used first to help the government seize control of the expropriated land and supervise its distribution, and later to set up cooperative farms. The land confiscated included 480,000 acres (190,000 ha) owned by United States corporations.[126] Months later, as retaliation, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower sharply reduced United States imports of Cuban sugar (Cuba's main cash crop), thus leading Guevara on July 10, 1960, to address over 100,000 workers in front of the Presidential Palace at a rally called to denounce United States "economic aggression".[136] Time magazine reporters who met with Guevara around this time, described him as "guid(ing) Cuba with icy calculation, vast competence, high intelligence, and a perceptive sense of humor."[9]

Along with land reform, one of the primary areas that Guevara stressed needed national improvement was in the area of literacy. Before 1959 the official literacy rate for Cuba was between 60–76%, with educational access in rural areas and a lack of instructors the main determining factors.[137] As a result, the Cuban government at Guevara's behest dubbed 1961 the "year of education", and mobilized over 100,000 volunteers into "literacy brigades", who were then sent out into the countryside to construct schools, train new educators, and teach the predominantly illiterate guajiros (peasants) to read and write.[78][137] Unlike many of Guevara's later economic initiatives, this campaign was "a remarkable success". By the completion of the Cuban Literacy Campaign, 707,212 adults had been taught to read and write, raising the national literacy rate to 96%.[137]

— Urbano (a.k.a. Leonardo Tamayo),

fought with Guevara in Cuba and Bolivia[138]

Accompanying literacy, Guevara was also concerned with establishing universal access to higher education. To accomplish this, the new regime introduced affirmative action to the universities. While announcing this new commitment, Guevara told the gathered faculty and students at the University of Las Villas that the days when education was "a privilege of the white middle class" had ended. "The University" he said, "must paint itself black, mulatto, worker, and peasant." If it did not, he warned, the people would break down its doors "and paint the University the colors they like."[139]

Marxist ideological influence

The merit of Marx is that he suddenly produces a qualitative change in the history of social thought. He interprets history, understands its dynamic, predicts the future, but in addition to predicting it (which would satisfy his scientific obligation), he expresses a revolutionary concept: the world must not only be interpreted, it must be transformed. Man ceases to be the slave and tool of his environment and converts himself into the architect of his own destiny.— Che Guevara, Notes for the Study of the Ideology of the Cuban, October 1960 [140]

In September 1960, when Guevara was asked about Cuba’s ideology at the First Latin American Congress, he replied, "If l were asked whether our revolution is communist, l would define it as Marxist. Our revolution has discovered by its methods the paths that Marx pointed out."[141] Consequently, when enacting and advocating Cuban policy, Guevara cited the political philosopher Karl Marx as his ideological inspiration. In defending his political stance, Guevara confidently remarked, "There are truths so evident, so much a part of people's knowledge, that it is now useless to discuss them. One ought to be Marxist with the same naturalness with which one is 'Newtonian' in physics, or 'Pasteurian' in biology."[140] According to Guevara, the "practical revolutionaries" of the Cuban Revolution had the goal of "simply fulfill(ing) laws foreseen by Marx, the scientist."[140] Using Marx's predictions and system of dialectical materialism, Guevara professed that "The laws of Marxism are present in the events of the Cuban Revolution, independently of what its leaders profess or fully know of those laws from a theoretical point of view."[140]

The "New Man", Bay of Pigs, and missile crisis

Man truly achieves his full human condition when he produces without being compelled by the physical necessity of selling himself as a commodity.— Che Guevara, Man and Socialism in Cuba[142]

At this stage, Guevara acquired the additional position of Finance Minister, as well as President of the National Bank. These appointments, combined with his existing position as Minister of Industries, placed Guevara at the zenith of his power, as the "virtual czar" of the Cuban economy.[136] As a consequence of his position at the head of the central bank, it was now Guevara's duty to sign the Cuban currency, which per custom would bear his signature. Instead of using his full name, he signed the bills solely "Che".[143] It was through this symbolic act, which horrified many in the Cuban financial sector, that Guevara signaled his distaste for money and the class distinctions it brought about.[143] Guevara's long time friend Ricardo Rojo later remarked that "the day he signed Che on the bills, (he) literally knocked the props from under the widespread belief that money was sacred."[144]

In an effort to eliminate social inequalities, Guevara and Cuba's new leadership had moved to swiftly transform the political and economic base of the country through nationalizing factories, banks, and businesses, while attempting to ensure affordable housing, healthcare, and employment for all Cubans.[146] However, in order for a genuine transformation of consciousness to take root, Guevara believed that such structural changes would have to be accompanied by a conversion in people's social relations and values. Believing that the attitudes in Cuba towards race, women, individualism, and manual labor were the product of the island's outdated past, Guevara urged all individuals to view each other as equals and take on the values of what he termed "el Hombre Nuevo" (the New Man).[146] Guevara hoped his "new man" would ultimately be "selfless and cooperative, obedient and hard working, gender-blind, incorruptible, non-materialistic, and anti-imperialist".[146] To accomplish this, Guevara emphasized the tenets of Marxism–Leninism, and wanted to use the state to emphasize qualities such as egalitarianism and self-sacrifice, at the same time as "unity, equality, and freedom" became the new maxims.[146] Guevara's first desired economic goal of the new man, which coincided with his aversion for wealth condensation and economic inequality, was to see a nationwide elimination of material incentives in favor of moral ones. He negatively viewed capitalism as a "contest among wolves" where "one can only win at the cost of others" and thus desired to see the creation of a "new man and woman".[147] Guevara continually stressed that a socialist economy in itself is not "worth the effort, sacrifice, and risks of war and destruction" if it ends up encouraging "greed and individual ambition at the expense of collective spirit".[148] A primary goal of Guevara's thus became to reform "individual consciousness" and values to produce better workers and citizens.[148] In his view, Cuba's "new man" would be able to overcome the "egotism" and "selfishness" that he loathed and discerned was uniquely characteristic of individuals in capitalist societies.[148] To promote this concept of a "new man", the government also created a series of party-dominated institutions and mechanisms on all levels of society, which included organizations such as labor groups, youth leagues, women's groups, community centers, and houses of culture to promote state-sponsored art, music, and literature. In congruence with this, all educational, mass media, and artistic community based facilities were nationalized and utilized to instill the government's official socialist ideology.[146] In describing this new method of "development", Guevara stated:

There is a great difference between free-enterprise development and revolutionary development. In one of them, wealth is concentrated in the hands of a fortunate few, the friends of the government, the best wheeler-dealers. In the other, wealth is the people's patrimony.[149]

A further integral part of fostering a sense of "unity between the individual and the mass", Guevara believed, was volunteer work and will. To display this, Guevara "led by example", working "endlessly at his ministry job, in construction, and even cutting sugar cane" on his day off.[150] He was known for working 36 hours at a stretch, calling meetings after midnight, and eating on the run.[148] Such behavior was emblematic of Guevara's new program of moral incentives, where each worker was now required to meet a quota and produce a certain quantity of goods. As a replacement for the pay increases abolished by Guevara, workers who exceeded their quota now only received a certificate of commendation, while workers who failed to meet their quotas were given a pay cut.[148] Guevara unapologetically defended his personal philosophy towards motivation and work, stating:

This is not a matter of how many pounds of meat one might be able to eat, or how many times a year someone can go to the beach, or how many ornaments from abroad one might be able to buy with his current salary. What really matters is that the individual feels more complete, with much more internal richness and much more responsibility.[151]

In the face of a loss of commercial connections with Western states, Guevara tried to replace them with closer commercial relationships with Eastern Bloc states, visiting a number of Marxist states and signing trade agreements with them. At the end of 1960 he visited Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, North Korea, Hungary and East Germany and signed, for instance, a trade agreement in East Berlin on December 17, 1960.[152] Such agreements helped Cuba's economy to a certain degree but also had the disadvantage of a growing economic dependency on the Eastern Bloc. It was also in East Germany where Guevara met Tamara Bunke (later known as "Tania"), who was assigned as his interpreter, and who would years later join him, and be killed with him in Bolivia.

Whatever the merits or demerits of Guevara's economic principles, his programs were unsuccessful.[153] Guevara's program of "moral incentives" for workers caused a rapid drop in productivity and a rapid rise in absenteeism.[154] Decades later, the director of Radio Martí Ernesto Betancourt, an early ally turned Castro-critic and Che's former deputy, would accuse Guevara of being "ignorant of the most elementary economic principles."[155] In reference to the collective failings of Guevara's vision, reporter I. F. Stone who interviewed Guevara twice during this time, remarked that he was "Galahad not Robespierre", while opining that "in a sense he was, like some early saint, taking refuge in the desert. Only there could the purity of the faith be safeguarded from the unregenerate revisionism of human nature".[156]

On April 17, 1961, 1,400 U.S.-trained Cuban exiles invaded Cuba during the Bay of Pigs Invasion. Guevara did not play a key role in the fighting, as one day before the invasion a warship carrying Marines faked an invasion off the West Coast of Pinar del Río and drew forces commanded by Guevara to that region. However, historians give him a share of credit for the victory as he was director of instruction for Cuba's armed forces at the time.[11] Author Tad Szulc in his explanation of the Cuban victory, assigns Guevara partial credit, stating: "The revolutionaries won because Che Guevara, as the head of the Instruction Department of the Revolutionary Armed Forces in charge of the militia training program, had done so well in preparing 200,000 men and women for war."[11] It was also during this deployment that he suffered a bullet grazing to the cheek when his pistol fell out of its holster and accidentally discharged.[157]

In August 1961, during an economic conference of the Organization of American States in Punta del Este, Uruguay, Che Guevara sent a note of "gratitude" to United States President John F. Kennedy through Richard N. Goodwin, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs. It read "Thanks for Playa Girón (Bay of Pigs). Before the invasion, the revolution was shaky. Now it's stronger than ever."[158][159] In response to United States Treasury Secretary Douglas Dillon presenting the Alliance for Progress for ratification by the meeting, Guevara antagonistically attacked the United States claim of being a "democracy", stating that such a system was not compatible with "financial oligarchy, discrimination against blacks, and outrages by the Ku Klux Klan".[160] Guevara continued, speaking out against the "persecution" that in his view "drove scientists like Oppenheimer from their posts, deprived the world for years of the marvelous voice of Paul Robeson, and sent the Rosenbergs to their deaths against the protests of a shocked world."[160] Guevara ended his remarks by insinuating that the United States was not interested in real reforms, sardonically quipping that "U.S. experts never talk about agrarian reform; they prefer a safe subject, like a better water supply. In short, they seem to prepare the revolution of the toilets."[161] Nevertheless, Goodwin stated in his memo to President Kennedy following the meeting that Guevara viewed him as someone of the "newer generation"[162] and that Guevara, whom Goodwin alleged sent a message to him the day after the meeting through one of the meeting's Argentine participants whom he described as "Darretta,"[162] also viewed the conservation which the two had as "quite profitable."[162]

Guevara, who was practically the architect of the Soviet–Cuban relationship,[163] then played a key role in bringing to Cuba the Soviet nuclear-armed ballistic missiles that precipitated the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 and brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.[164] A few weeks after the crisis, during an interview with the British communist newspaper the Daily Worker, Guevara was still fuming over the perceived Soviet betrayal and told correspondent Sam Russell that, if the missiles had been under Cuban control, they would have fired them off.[165] While expounding on the incident later, Guevara reiterated that the cause of socialist liberation against global "imperialist aggression" would ultimately have been worth the possibility of "millions of atomic war victims".[166] The missile crisis further convinced Guevara that the world's two superpowers (the United States and the Soviet Union) used Cuba as a pawn in their own global strategies. Afterward, he denounced the Soviets almost as frequently as he denounced the Americans.[167]

International diplomacy

In December 1964, Che Guevara had emerged as a "revolutionary statesman of world stature" and thus traveled to New York City as head of the Cuban delegation to speak at the United Nations.[144] On December 11, 1964, during Guevara's hour-long, impassioned address at the UN, he criticized the United Nations' inability to confront the "brutal policy of apartheid" in South Africa, asking "Can the United Nations do nothing to stop this?"[168] Guevara then denounced the United States policy towards their black population, stating:

Those who kill their own children and discriminate daily against them because of the color of their skin; those who let the murderers of blacks remain free, protecting them, and furthermore punishing the black population because they demand their legitimate rights as free men—how can those who do this consider themselves guardians of freedom?[168]

An indignant Guevara ended his speech by reciting the Second Declaration of Havana, decreeing Latin America a "family of 200 million brothers who suffer the same miseries".[168] This "epic", Guevara declared, would be written by the "hungry Indian masses, peasants without land, exploited workers, and progressive masses". To Guevara the conflict was a struggle of masses and ideas, which would be carried forth by those "mistreated and scorned by imperialism" who were previously considered "a weak and submissive flock". With this "flock", Guevara now asserted, "Yankee monopoly capitalism" now terrifyingly saw their "gravediggers".[168] It would be during this "hour of vindication", Guevara pronounced, that the "anonymous mass" would begin to write its own history "with its own blood" and reclaim those "rights that were laughed at by one and all for 500 years". Guevara closed his remarks to the General Assembly by hypothesizing that this "wave of anger" would "sweep the lands of Latin America" and that the labor masses who "turn the wheel of history" were now, for the first time, "awakening from the long, brutalizing sleep to which they had been subjected".[168]

Guevara later learned there had been two failed attempts on his life by Cuban exiles during his stop at the UN complex.[169] The first from Molly Gonzales, who tried to break through barricades upon his arrival with a seven-inch hunting knife, and later during his address by Guillermo Novo, who fired a timer-initiated bazooka from a boat in the East River at the United Nations Headquarters, but missed and was off target. Afterwards Guevara commented on both incidents, stating that "it is better to be killed by a woman with a knife than by a man with a gun", while adding with a languid wave of his cigar that the explosion had "given the whole thing more flavor".[169]

While in New York, Guevara appeared on the CBS Sunday news program Face the Nation,[170] and met with a wide range of people, from United States Senator Eugene McCarthy[171] to associates of Malcolm X. The latter expressed his admiration, declaring Guevara "one of the most revolutionary men in this country right now" while reading a statement from him to a crowd at the Audubon Ballroom.[172]

On December 17, Guevara left New York for Paris, France, and from there embarked on a three-month world tour that included visits to the People's Republic of China, North Korea, the United Arab Republic, Algeria, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Dahomey, Congo-Brazzaville and Tanzania, with stops in Ireland and Prague. While in Ireland, Guevara embraced his own Irish heritage, celebrating Saint Patrick's Day in Limerick city.[173] He wrote to his father on this visit, humorously stating "I am in this green Ireland of your ancestors. When they found out, the television [station] came to ask me about the Lynch genealogy, but in case they were horse thieves or something like that, I didn't say much."[174]

During this voyage, he wrote a letter to Carlos Quijano, editor of a Uruguayan weekly, which was later retitled Socialism and Man in Cuba.[147] Outlined in the treatise was Guevara's summons for the creation of a new consciousness, a new status of work, and a new role of the individual. He also laid out the reasoning behind his anti-capitalist sentiments, stating:

The laws of capitalism, blind and invisible to the majority, act upon the individual without his thinking about it. He sees only the vastness of a seemingly infinite horizon before him. That is how it is painted by capitalist propagandists, who purport to draw a lesson from the example of Rockefeller—whether or not it is true—about the possibilities of success. The amount of poverty and suffering required for the emergence of a Rockefeller, and the amount of depravity that the accumulation of a fortune of such magnitude entails, are left out of the picture, and it is not always possible to make the people in general see this.[147]

Guevara ended the essay by declaring that "the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love" and beckoning on all revolutionaries to "strive every day so that this love of living humanity will be transformed into acts that serve as examples", thus becoming "a moving force".[147] The genesis for Guevara's assertions relied on the fact that he believed the example of the Cuban Revolution was "something spiritual that would transcend all borders".[34]

Algiers, the Soviets, and China

In Algiers, Algeria, on February 24, 1965, Guevara made what turned out to be his last public appearance on the international stage when he delivered a speech at an economic seminar on Afro-Asian solidarity.[175] He specified the moral duty of the socialist countries, accusing them of tacit complicity with the exploiting Western countries. He proceeded to outline a number of measures which he said the communist-bloc countries must implement in order to accomplish the defeat of imperialism.[176] Having criticized the Soviet Union (the primary financial backer of Cuba) in such a public manner, he returned to Cuba on March 14 to a solemn reception by Fidel and Raúl Castro, Osvaldo Dorticós and Carlos Rafael Rodríguez at the Havana airport.

As revealed in his last public speech in Algiers, Guevara had come to view the Northern Hemisphere, led by the U.S. in the West and the Soviet Union in the East, as the exploiter of the Southern Hemisphere. He strongly supported Communist North Vietnam in the Vietnam War, and urged the peoples of other developing countries to take up arms and create "many Vietnams".[177] Che's denunciations of the Soviets made him popular among intellectuals and artists of the Western European left who had lost faith in the Soviet Union, while his condemnation of imperialism and call to revolution inspired young radical students in the United States, who were impatient for societal change.[178]

— Helen Yaffe, author of Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution[179]

In Guevara's private writings from this time (since released), he displays his growing criticism of the Soviet political economy, believing that the Soviets had "forgotten Marx".[179] This led Guevara to denounce a range of Soviet practices including what he saw as their attempt to "air-brush the inherent violence of class struggle integral to the transition from capitalism to socialism", their "dangerous" policy of peaceful co-existence with the United States, their failure to push for a "change in consciousness" towards the idea of work, and their attempt to "liberalize" the socialist economy. Guevara wanted the complete elimination of money, interest, commodity production, the market economy, and "mercantile relationships": all conditions that the Soviets argued would only disappear when world communism was achieved.[179] Disagreeing with this incrementalist approach, Guevara criticized the Soviet Manual of Political Economy, correctly predicting that if USSR would not abolish the law of value (as Guevara desired), it would eventually return to capitalism.[179]

Two weeks after his Algiers speech and his return to Cuba, Guevara dropped out of public life and then vanished altogether.[180] His whereabouts were a great mystery in Cuba, as he was generally regarded as second in power to Castro himself. His disappearance was variously attributed to the failure of the Cuban industrialization scheme he had advocated while minister of industries, to pressure exerted on Castro by Soviet officials disapproving of Guevara's pro-Chinese Communist stance on the Sino-Soviet split, and to serious differences between Guevara and the pragmatic Castro regarding Cuba's economic development and ideological line.[181] Pressed by international speculation regarding Guevara's fate, Castro stated on June 16, 1965, that the people would be informed when Guevara himself wished to let them know. Still, rumors spread both inside and outside Cuba to the missing Guevara's whereabouts.

On October 3, 1965, Castro publicly revealed an undated letter purportedly written to him by Guevara around seven months earlier which was later titled Che Guevara's "farewell letter". In the letter, Guevara reaffirmed his enduring solidarity with the Cuban Revolution but declared his intention to leave Cuba to fight for the revolutionary cause abroad. Additionally, he resigned from all his positions in the Cuban government and communist party, and renounced his honorary Cuban citizenship.[182]

Congo

In early 1965, Guevara went to Africa to offer his knowledge and experience as a guerrilla to the ongoing conflict in the Congo. According to Algerian President Ahmed Ben Bella, Guevara thought that Africa was imperialism's weak link and so had enormous revolutionary potential.[183] Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had fraternal relations with Che since his 1959 visit, saw Guevara's plan to fight in Congo as "unwise" and warned that he would become a "Tarzan" figure, doomed to failure.[184] Despite the warning, Guevara traveled to Congo using the alias Ramón Benítez.[185] He led the Cuban operation in support of the Marxist Simba movement, which had emerged from the ongoing Congo crisis. Guevara, his second-in-command Víctor Dreke, and 12 other Cuban expeditionaries arrived in Congo on April 24, 1965, and a contingent of approximately 100 Afro-Cubans joined them soon afterward.[186][187] For a time, they collaborated with guerrilla leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila, who had helped supporters of the overthrown president Patrice Lumumba to lead an unsuccessful revolt months earlier. As an admirer of the late Lumumba, Guevara declared that his "murder should be a lesson for all of us".[188] Guevara, with limited knowledge of Swahili and the local languages, was assigned a teenage interpreter, Freddy Ilanga. Over the course of seven months, Ilanga grew to "admire the hard-working Guevara", who "showed the same respect to black people as he did to whites".[189] However, Guevara soon became disillusioned with the poor discipline of Kabila's troops and later dismissed him, stating "nothing leads me to believe he is the man of the hour".[190]

As an additional obstacle, white mercenaries, led by Mike Hoare in league with Cuban exiles and the CIA, worked with the Congo National Army to thwart Guevara's movements from his base camp in the mountains near the village of Fizi on Lake Tanganyika in southeast Congo. They were able to monitor his communications and so pre-empted his attacks and interdicted his supply lines. Although Guevara tried to conceal his presence in Congo, the United States government knew his location and activities. The National Security Agency was intercepting all of his incoming and outgoing transmissions via equipment aboard the USNS Private Jose F. Valdez (T-AG-169), a floating listening post that continuously cruised the Indian Ocean off Dar es Salaam for that purpose.[191]

Guevara's aim was to export the revolution by instructing local anti-Mobutu Simba fighters in Marxist ideology and foco theory strategies of guerrilla warfare. In his Congo Diary book, he cites the incompetence, intransigence and infighting among the Congolese rebels as key reasons for the revolt's failure.[192] Later that year on November 20, 1965, suffering from dysentery and acute asthma, and disheartened after seven months of defeats, Guevara left Congo with the six Cuban survivors of his 12-man column. Guevara stated that he had planned to send the wounded back to Cuba and fight in Congo alone until his death, as a revolutionary example. But after being urged by his comrades, and two emissaries sent by Castro, at the last moment he reluctantly agreed to leave Africa. During that day and night, Guevara's forces quietly took down their base camp, burned their huts, and destroyed or threw weapons into Lake Tanganyika that they could not take with them, before crossing the border into Tanzania at night and traveling by land to Dar es Salaam. In speaking about his experience in Congo months later, Guevara concluded that he left rather than fight to the death because: "The human element failed. There is no will to fight. The leaders are corrupt. In a word ... there was nothing to do."[193] Guevara also declared that "we can't liberate by ourselves a country that does not want to fight."[194] A few weeks later, he wrote the preface to the diary he kept during the Congo venture, that began: "This is the history of a failure."[195]

Guevara was reluctant to return to Cuba, because Castro had made public Guevara's "farewell letter"—a letter intended to only be revealed in the case of his death—wherein he severed all ties in order to devote himself to revolution throughout the world.[196] As a result, Guevara spent the next six months living clandestinely in Dar es Salaam and Prague.[197] During this time, he compiled his memoirs of the Congo experience and wrote drafts of two more books, one on philosophy and the other on economics. As Guevara prepared for Bolivia, he secretly traveled back to Cuba to visit Castro, as well as to see his wife and to write a last letter to his five children to be read upon his death, which ended with him instructing them:

Above all, always be capable of feeling deeply any injustice committed against anyone, anywhere in the world. This is the most beautiful quality in a revolutionary.[198]

Bolivia

In late 1966, Guevara's location was still not public knowledge, although representatives of Mozambique's independence movement, the FRELIMO, reported that they met with Guevara in late 1966 in Dar es Salaam regarding his offer to aid in their revolutionary project, an offer which they ultimately rejected.[199] In a speech at the 1967 International Workers' Day rally in Havana, the acting minister of the armed forces, Major Juan Almeida, announced that Guevara was "serving the revolution somewhere in Latin America".

Before he departed for Bolivia, Guevara altered his appearance by shaving off his beard and much of his hair, also dying it grey so he would be unrecognizable as Che Guevara.[200] On November 3, 1966, Guevara secretly arrived in La Paz on a flight from Montevideo under the false name Adolfo Mena González, posing as a middle-aged Uruguayan businessman working for the Organization of American States.[201]

Three days after his arrival in Bolivia, Guevara left La Paz for the rural south east region of the country to form his guerrilla army. Guevara's first base camp was located in the montane dry forest in the remote Ñancahuazú region. Training at the camp in the Ñancahuazú valley proved to be hazardous, and little was accomplished in way of building a guerrilla army. The Argentine-born East German operative Haydée Tamara Bunke Bider, better known by her nom de guerre "Tania", had been installed as Che's primary agent in La Paz.[202][203]

Guevara's guerrilla force, numbering about 50 men[204] and operating as the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional de Bolivia; "National Liberation Army of Bolivia"), was well equipped and scored a number of early successes against Bolivian army regulars in the difficult terrain of the mountainous Camiri region during the early months of 1967. As a result of Guevara's units' winning several skirmishes against Bolivian troops in the spring and summer of 1967, the Bolivian government began to overestimate the true size of the guerrilla force.[205] But in August 1967, the Bolivian Army managed to eliminate two guerrilla groups in a violent battle, reportedly killing one of the leaders.

Researchers hypothesize that Guevara's plan for fomenting a revolution in Bolivia failed for an array of reasons:

- He had expected to deal only with the Bolivian military, who were poorly trained and equipped, and was unaware that the United States government had sent a team of the CIA's Special Activities Division commandos and other operatives into Bolivia to aid the anti-insurrection effort. The Bolivian Army would also be trained, advised, and supplied by U.S. Army Special Forces, including a recently organized elite battalion of U.S. Rangers trained in jungle warfare that set up camp in La Esperanza, a small settlement close to the location of Guevara's guerrillas.[206]

- Guevara had expected assistance and cooperation from the local dissidents that he did not receive, nor did he receive support from Bolivia's Communist Party under the leadership of Mario Monje, which was oriented toward Moscow rather than Havana. In Guevara's own diary captured after his death, he wrote about the Communist Party of Bolivia, which he characterized as "distrustful, disloyal and stupid".[207]

- He had expected to remain in radio contact with Havana. The two shortwave radio transmitters provided to him by Cuba were faulty; thus, the guerrillas were unable to communicate and be resupplied, leaving them isolated and stranded.

In addition, Guevara's known preference for confrontation rather than compromise, which had previously surfaced during his guerrilla warfare campaign in Cuba, contributed to his inability to develop successful working relationships with local rebel leaders in Bolivia, just as it had in the Congo.[208] This tendency had existed in Cuba, but had been kept in check by the timely interventions and guidance of Fidel Castro.[209]

The end result was that Guevara was unable to attract inhabitants of the local area to join his militia during the eleven months he attempted recruitment. Many of the inhabitants willingly informed the Bolivian authorities and military about the guerrillas and their movements in the area. Near the end of the Bolivian venture, Guevara wrote in his diary that "the peasants do not give us any help, and they are turning into informers."[210]

Capture and death

— Philip Agee, CIA agent from 1957–1968, later defected to Cuba [211]

Félix Rodríguez, a Cuban exile turned CIA Special Activities Division operative, advised Bolivian troops during the hunt for Guevara in Bolivia.[212] In addition, the 2007 documentary My Enemy's Enemy alleges that Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie advised and possibly helped the CIA orchestrate Guevara's eventual capture.[213]

On October 7, 1967, an informant apprised the Bolivian Special Forces of the location of Guevara's guerrilla encampment in the Yuro ravine.[214] On the morning of October 8, they encircled the area with two battalions numbering 1,800 soldiers and advanced into the ravine triggering a battle where Guevara was wounded and taken prisoner while leading a detachment with Simeón Cuba Sarabia. Che biographer Jon Lee Anderson reports Bolivian Sergeant Bernardino Huanca's account: that as the Bolivian Rangers approached, a twice-wounded Guevara, his gun rendered useless, threw up his arms in surrender and shouted to the soldiers: "Do not shoot! I am Che Guevara and I am worth more to you alive than dead."[215]

Guevara was tied up and taken to a dilapidated mud schoolhouse in the nearby village of La Higuera on the evening of October 8. For the next half day, Guevara refused to be interrogated by Bolivian officers and would only speak quietly to Bolivian soldiers. One of those Bolivian soldiers, a helicopter pilot named Jaime Nino de Guzman, describes Che as looking "dreadful". According to Guzman, Guevara was shot through the right calf, his hair was matted with dirt, his clothes were shredded, and his feet were covered in rough leather sheaths. Despite his haggard appearance, he recounts that "Che held his head high, looked everyone straight in the eyes and asked only for something to smoke." De Guzman states that he "took pity" and gave him a small bag of tobacco for his pipe, and that Guevara then smiled and thanked him.[216] Later on the night of October 8, Guevara—despite having his hands tied—kicked a Bolivian army officer, named Captain Espinosa, against a wall after the officer entered the schoolhouse and tried to snatch Guevara's pipe from his mouth as a souvenir while he was still smoking it.[217] In another instance of defiance, Guevara spat in the face of Bolivian Rear Admiral Ugarteche, who attempted to question Guevara a few hours before his execution.[217]

The following morning on October 9, Guevara asked to see the school teacher of the village, a 22-year-old woman named Julia Cortez. Cortez would later state that she found Guevara to be an "agreeable looking man with a soft and ironic glance" and that during their conversation she found herself "unable to look him in the eye" because his "gaze was unbearable, piercing, and so tranquil".[217] During their short conversation, Guevara pointed out to Cortez the poor condition of the schoolhouse, stating that it was "anti-pedagogical" to expect campesino students to be educated there, while "government officials drive Mercedes cars", and declaring "that's what we are fighting against."[217]

Later that morning on October 9, Bolivian President René Barrientos ordered that Guevara be killed. The order was relayed to the unit holding Guevara by Félix Rodríguez despite the United States government's desire that Guevara be taken to Panama for further interrogation.[218] The executioner who volunteered to kill Guevara was Mario Terán, an alcoholic 27-year-old sergeant in the Bolivian army who had personally requested to shoot Guevara because three of his friends from B Company, all with the same first name of "Mario", had been killed in an earlier firefight with Guevara's band of guerrillas.[10] To make the bullet wounds appear consistent with the story that the Bolivian government planned to release to the public, Félix Rodríguez ordered Terán not to shoot Guevara in the head, but to aim carefully to make it appear that Guevara had been killed in action during a clash with the Bolivian army.[219] Gary Prado, the Bolivian captain in command of the army company that captured Guevara, said that the reasons Barrientos ordered the immediate execution of Guevara were so there would be no possibility for Guevara to escape from prison, and also so there would be no drama in regard to a public trial where adverse publicity might happen.[220]

About 30 minutes before Guevara was killed, Félix Rodríguez attempted to question him about the whereabouts of other guerrilla fighters who were currently at large, but Guevara continued to remain silent. Rodríguez, assisted by a few Bolivian soldiers, helped Guevara to his feet and took him outside the hut to parade him before other Bolivian soldiers where he posed with Guevara for a photo opportunity where one soldier took a photograph of Rodríguez and other soldiers standing alongside Guevara. Afterwords, Rodríguez told Guevara that he was going to be executed. A little later, Guevara was asked by one of the Bolivian soldiers guarding him if he was thinking about his own immortality. "No," he replied, "I'm thinking about the immortality of the revolution."[221] A few minutes later, Sergeant Terán entered the hut to shoot him, whereupon Guevara reportedly spoke to Terán which were his last words: "I know you've come to kill me. Shoot, coward! You are only going to kill a man!" Terán hesitated, then pointed his self-loading M2 carbine[222] at Guevara and opened fire, hitting him in the arms and legs.[223] Then, as Guevara writhed on the ground, apparently biting one of his wrists to avoid crying out, Terán fired another burst, fatally wounding him in the chest. Guevara was pronounced dead at 1:10 pm local time according to Rodríguez.[223] In all, Guevara was shot nine times by Terán. This included five times in his legs, once in the right shoulder and arm, and once in the chest and throat.[217]

Months earlier, during his last public declaration to the Tricontinental Conference,[177] Guevara wrote his own epitaph, stating "Wherever death may surprise us, let it be welcome, provided that this our battle cry may have reached some receptive ear and another hand may be extended to wield our weapons."[224]

Post-execution and memorial

After his execution, Guevara's body was lashed to the landing skids of a helicopter and flown to nearby Vallegrande, where photographs were taken of him lying on a concrete slab in the laundry room of the Nuestra Señora de Malta.[225] Several witnesses were called to confirm his identity, key amongst them the British journalist Richard Gott, the only witness to have met Guevara when he was alive. Put on display, as hundreds of local residents filed past the body, Guevara's corpse was considered by many to represent a "Christ-like" visage, with some even surreptitiously clipping locks of his hair as divine relics.[226] Such comparisons were further extended when English art critic John Berger, two weeks later upon seeing the post-mortem photographs, observed that they resembled two famous paintings: Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp and Andrea Mantegna's Lamentation over the Dead Christ.[227] There were also four correspondents present when Guevara's body arrived in Vallegrande, including Björn Kumm of the Swedish Aftonbladet, who described the scene in a November 11, 1967, exclusive for The New Republic.[228]

A declassified memorandum dated October 11, 1967, to United States President Lyndon B. Johnson from his National Security Advisor Walt Whitman Rostow, called the decision to kill Guevara "stupid" but "understandable from a Bolivian standpoint".[229] After the execution Rodríguez took several of Guevara's personal items—including a Rolex GMT Master wristwatch[230] that he continued to wear many years later—often showing them to reporters during the ensuing years. After a military doctor amputated his hands, Bolivian army officers transferred Guevara's body to an undisclosed location and refused to reveal whether his remains had been buried or cremated. The hands were preserved in formaldehyde to be sent to Buenos Aires for fingerprint identification. (His fingerprints were on file with the Argentine police.) They were later sent to Cuba.