Ernest Mason Satow

| The Right Honourable Sir Ernest Mason Satow GCMG | |

|---|---|

|

The young Ernest Mason Satow. Photograph taken in Paris, December 1869. | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

30 June 1843 Clapton, London, England |

| Died |

26 August 1929 (aged 86) Ottery St Mary, England |

| Spouse(s) | Takeda Kane (1853–1932) |

| Children |

Takeda Eitaro Takeda Hisayoshi (1883–1972) |

| Parents |

Hans David Christoph Satow Margaret Mason |

| Education |

Mill Hill School University College London |

| Occupation | Diplomat |

Sir Ernest Mason Satow, GCMG, PC (30 June 1843 – 26 August 1929), was a British scholar, diplomat and Japanologist.[1]

Satow was born to an ethnically German father (Hans David Christoph Satow, born in Wismar, then under Swedish rule, naturalised British in 1846) and an English mother (Margaret, née Mason) in Clapton, North London. He was educated at Mill Hill School and University College London (UCL).

Satow was an exceptional linguist, an energetic traveller, a writer of travel guidebooks, a dictionary compiler, a mountaineer, a keen botanist (chiefly with F. V. Dickins) and a major collector of Japanese books and manuscripts on all kinds of subjects. He also loved classical music and the works of Dante on which his brother-in-law Henry Fanshawe Tozer was an authority. Satow kept a diary for most of his adult life which amounts to 47 mostly handwritten volumes.

As a celebrity, albeit not a major one, he was the subject of a cartoon portrait by Spy in the British Vanity Fair magazine, 23 April 1903.

General

Satow is better known in Japan than in Britain or the other countries in which he served. He was a key figure in East Asia and Anglo-Japanese relations, particularly in Bakumatsu- (1853–1867) and Meiji-period (1868–1912) Japan, and in China after the Boxer Rebellion, 1900–06. He also served in Siam, Uruguay and Morocco, and represented Britain at the Second Hague Peace Conference in 1907. In his retirement he wrote A Guide to Diplomatic Practice, now known as 'Satow's Guide to Diplomatic Practice' – this manual is widely used today, and has been updated several times by distinguished diplomats, notably Lord Gore-Booth. The sixth edition edited by Sir Ivor Roberts was published by Oxford University Press in 2009, and is over 700 pages long.

Satow's diplomatic career

Japan (1862–1883)

Ernest Satow is probably best known as the author of the book A Diplomat in Japan (based mainly on his diaries) which describes the years 1862–1869 when Japan was changing from rule by the Tokugawa shogunate to the restoration of Imperial rule. He was recruited by the Foreign Office straight out of university in London. Within a week of his arrival by way of China as a young student interpreter in the British Japan Consular Service, at age 19, the Namamugi Incident (Namamugi Jiken), in which a British merchant was killed on the Tōkaidō, took place on 21 August 1862. Satow was on board one of the British ships which sailed to Kagoshima in August 1863 to obtain the compensation demanded from the Satsuma clan's daimyō, Shimazu Hisamitsu, for the slaying of Charles Lennox Richardson. They were fired on by the Satsuma shore batteries and retaliated, an action that became known in Britain as the Bombardment of Kagoshima.

In 1864, Satow was with the allied force (Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States) which attacked Shimonoseki to enforce the right of passage of foreign ships through the narrow Kanmon Straits between Honshū and Kyūshū. Satow met Itō Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru of Chōshū for the first time just before the bombardment of Shimonoseki. He also had links with many other Japanese leaders, including Saigō Takamori of Satsuma (who became a friend), and toured the hinterland of Japan with A. B. Mitford and the cartoonist and illustrator Charles Wirgman.

Satow's rise in the consular service was due at first to his competence and zeal as an interpreter at a time when English was virtually unknown in Japan, the Japanese government still communicated with the West in Dutch and available study aids were exceptionally few. Employed as a consular interpreter alongside Russell Robertson, Satow became a student of Rev. Samuel Robbins Brown, and an associate of Dr. James Curtis Hepburn, two noted pioneers in the study of the Japanese language.[2][3] His Japanese language skills quickly became indispensable in the British Minister Sir Harry Parkes's negotiations with the failing Tokugawa shogunate and the powerful Satsuma and Chōshū clans, and the gathering of intelligence. He was promoted to full Interpreter and then Japanese Secretary to the British legation, and, as early as 1864, he started to write translations and newspaper articles on subjects relating to Japan. In 1869, he went home to England on leave, returning to Japan in 1870.

Satow was one of the founding members at Yokohama, in 1872, of the Asiatic Society of Japan whose purpose was to study the Japanese culture, history and language (i.e. Japanology) in detail. He lectured to the Society on several occasions in the 1870s, and the Transactions of the Asiatic Society contain several of his published papers. The Society is still thriving today.[4]

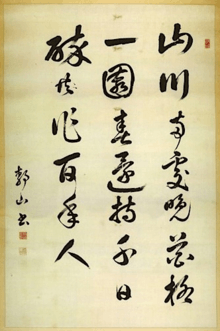

During his time in Japan, Satow devoted much effort to studying Chinese calligraphy under Kōsai Tanzan 高斎単山 (1818–1890), who gave him the artist's name Seizan 静山 in 1873. An example of Satow's calligraphy, signed as Seizan, was acquired by the British Library in 2004.[5]

Siam, Uruguay, Morocco (1884–1895)

Satow served in Siam (1884–1887), during which time he was accorded the rare honour of promotion from the Consular to the Diplomatic service,[6] Uruguay (1889–93) and Morocco (1893–95). (Such promotion was extraordinary because the British Consular and Diplomatic services were segregated until the mid-20th century, and Satow did not come from the aristocratic class to which the Diplomatic Service was restricted.)

Japan (1895–1900)

Satow returned to Japan as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary on 28 July 1895.[7] He stayed in Tokyo for five years (though he was on leave in London for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897 and met her in August at Osborne House, Isle of Wight). On 17 April 1895 the Treaty of Shimonoseki (text here) had been signed, and Satow was able to observe at first hand the steady build-up of the Japanese army and navy to avenge the humiliation by Russia, Germany and France in the Triple Intervention of 23 April 1895. He was also in a position to oversee the transition to the ending of extraterritoriality in Japan which finally ended in 1899, as agreed by the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation signed in London on 16 July 1894.

On Satow's personal recommendation, Hiram Shaw Wilkinson, who had been a student interpreter in Japan 2 years after Satow, was appointed first, Judge of the British Court for Japan in 1897 and in 1900 Chief Justice of the British Supreme Court for China and Corea.[8]

Satow built a house at Lake Chūzenji in 1896 and went there frequently to relax and escape from the pressures of his work in Tokyo.[9]

Satow was unlucky not to be named the first British Ambassador to Japan, an honour which was bestowed on his successor Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald in 1905.

China (1900–1906)

Satow served as the British High Commissioner (September 1900 – January 1902) and then Minister in Peking from 1900–1906. He was active as plenipotentiary in the negotiations to conclude the Boxer Protocol which settled the compensation claims of the Powers after the Boxer Rebellion, and he signed the protocol for Britain on 7 September 1901. He received the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) in the 1902 Coronation Honours list.[10][11] Satow also observed the defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) from his Peking post. He signed the Convention Between Great Britain and China.

Retirement (1906–1929)

In 1906 Satow was made a Privy Councillor. In 1907 he was Britain's second plenipotentiary at the Second Hague Peace Conference.

In retirement (1906–1929) at Ottery St Mary in Devon, England, he wrote mainly on subjects connected with diplomacy and international law. In Britain, he is less well known than in Japan, where he is recognised as perhaps the most important foreign observer in the Bakumatsu and Meiji periods. He gave the Rede lecture at Cambridge University in 1908 on the career of Count Joseph Alexander Hübner. It was titled An Austrian Diplomat in the Fifties. Satow chose this subject with discretion to avoid censure from the British Foreign Office for discussing his own career.

As the years passed, Satow's understanding and appreciation of the Japanese evolved and deepened. For example, one of his diary entries from the early 1860s asserts that the submissive character of the Japanese will make it easy for foreigners to govern them after the "samurai problem" could be resolved; but in retirement, he wrote: "... looking back now in 1919, it seems perfectly ludicrous that such a notion should have been entertained, even as a joke, for a single moment, by anyone who understood the Japanese spirit."[12]

Satow's extensive diaries and letters (the Satow Papers, PRO 30/33 1-23) are kept at the Public Record Office at Kew, West London in accordance with his last will and testament. His letters to Geoffrey Drage, sometime MP, are held in the Library and Archives of Christ Church, Oxford. Many of his rare Japanese books are now part of the Oriental collection of Cambridge University Library and his collection of Japanese prints are in the British Museum.[13]

Family

Satow was never able, as a diplomat serving in Japan, to marry his Japanese common-law wife, Takeda Kane 武田兼 (1853–1932), by whom he had two sons, Eitaro and Hisayoshi, and a daughter.[5] The Takeda family letters, including many of Satow's to and from his family, have been deposited at the Yokohama Archives of History (formerly the British consulate in Yokohama) at the request of Satow's granddaughters.

Satow's second son, Takeda Hisayoshi, became a noted botanist, founder of the Japan Natural History Society and from 1948 to 1951 was President of the Japan Alpine Club. He studied at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and at Birmingham University. A memorial hall to him is in the Oze marshlands in Hinoemata, Fukushima Prefecture.

Selected works

- A Handbook for Travellers in Central and Northern Japan, by Ernest Mason Satow and A G S [Albert George Sidney] Hawes

- A Handbook for Travellers in Central and Northern Japan: Being a guide to Tōkiō, Kiōto, Ōzaka and other cities; the most interesting parts of the main island between Kōbe and Awomori, with ascents of the principal mountains, and descriptions of temples, historical notes and legends with maps and plans. Yokohama: Kelly & Co.; Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh; Hong Kong: Kelly & Walsh, 1881.

- A Handbook for Travellers in Central and Northern Japan: Being a guide to Tōkiō, Kiōto, Ōzaka, Hakodate, Nagasaki, and other cities; the most interesting parts of the main island; ascents of the principal mountains; descriptions of temples; and historical notes and legends. London: John Murray, 1884.[n 1]

- A Guide to Diplomatic Practice by Sir E. Satow, (Longmans, Green & Co. London & New York, 1917). A standard reference work used in many embassies across the world, and described by Sir Harold Nicolson in his book Diplomacy as "The standard work on diplomatic practice", and "admirable".[14] Sixth edition, edited by Sir Ivor Roberts (2009, ISBN 978-0-19-955927-5).

- A Diplomat in Japan by Sir E. Satow, first published by Seeley, Service & Co., London, 1921, reprinted in paperback by Tuttle, 2002. (Page numbers are slightly different in the two editions.) ISBN 4-925080-28-8

- The Voyage of John Saris, ed. by Sir E. M. Satow (Hakluyt Society, 1900)

- The Family Chronicle of the English Satows, by Ernest Satow, privately printed, Oxford 1925.

- Collected Works of Ernest Mason Satow Part One: Major Works 1998 (includes two works not published by Satow)

- Collected Works of Ernest Mason Satow Part Two: Collected Papers 2001

- 'British Policy', a series of three untitled articles written by Satow (anonymously) in the Japan Times (ed. Charles Rickerby), dated 16 March, 4 May (? date uncertain) and 19 May 1866 which apparently influenced many Japanese once it was translated and widely distributed under the title Eikoku sakuron (British policy), and probably helped to hasten the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Satow pointed out that the British and other treaties with foreign countries had been made by the Shogun on behalf of Japan, but that the Emperor's existence had not even been mentioned, thus calling into question their validity. Satow accused the Shogun of fraud, and demanded to know who was the 'real head' of Japan and further a revision of the treaties to reflect the political reality. He later admitted in A Diplomat in Japan (p. 155 of the Tuttle reprint edition, p. 159 of the first edition) that writing the articles had been 'altogether contrary to the rules of the service' (i.e. it is inappropriate for a diplomat or consular agent to interfere in the politics of a country in which he/she is serving). [The first and third articles are reproduced on pp. 566–75 of Grace Fox, Britain and Japan 1858–1883, Oxford: Clarendon Press 1969, but the second one has only been located in the Japanese translation. A retranslation from the Japanese back into English has been attempted in I. Ruxton, Bulletin of the Kyūshū Institute of Technology (Humanities, Social Sciences), No. 45, March 1997, pp. 33–41]

Books and articles based on the Satow Papers

- The Diaries and Letters of Sir Ernest Mason Satow (1843–1929), a Scholar-Diplomat in East Asia, edited by Ian C. Ruxton, Edwin Mellen Press, 1998 ISBN 0-7734-8248-2. (Translated into Japanese ISBN 4-8419-0316-X )

- Korea and Manchuria between Russia and Japan 1895–1904: the observations of Sir Ernest Satow, British Minister Plenipotentiary to Japan (1895–1900) and China (1900-1906), Selected and edited with a historical introduction, by George Alexander Lensen. – Sophia University in cooperation with Diplomatic Press, 1966 [No ISBN]

- A Diplomat in Siam by Ernest Satow C.M.G., Introduced and edited by Nigel Brailey (Orchid Press, Bangkok, reprinted 2002) ISBN 974-8304-73-6

- The Satow Siam Papers: The Private Diaries and Correspondence of Ernest Satow, edited by Nigel Brailey (Volume 1, 1884–85), Bangkok: The Historical Society, 1997

- The Rt. Hon. Sir Ernest Mason Satow G.C.M.G.: A Memoir, by Bernard M. Allen (1933)

- Satow, by T.G. Otte in Diplomatic Theory from Machievelli to Kissinger (Palgrave, Basingstoke and New York, 2001)

- "Not Proficient in Table-Thumping": Sir Ernest Satow at Peking, 1900–1906 by T.G. Otte in Diplomacy & Statecraft vol.13 no.2 (June 2002) pp. 161–200

- "A Manual of Diplomacy": The Genesis of Satow's Guide to Diplomatic Practice by T.G. Otte in Diplomacy & Statecraft vol.13 no.2 (June 2002) pp. 229–243

Other

- Early Japanese books in Cambridge University Library: a catalogue of the Aston, Satow, and von Siebold collections, Nozomu Hayashi & Peter Kornicki—Cambridge University Press, 1991. – (University of Cambridge Oriental publications; 40) ISBN 0-521-36496-5

- Diplomacy and Statecraft, Volume 13, Number 2 includes a special section on Satow by various contributors (June, 2002)

- Entry on Satow in the new Dictionary of National Biography by Dr. Nigel Brailey of Bristol University

Dramatisation

On September 1992, BBC Two screened a two-part dramatisation of Satow's life, titled A Diplomat in Japan in the Timewatch documentary strand. Written and directed by Christopher Railing, it starred Alan Parnaby as Satow, Benjamin Whitrow as Sir Harry Parkes, Hitomi Tanabe as Takeda Kane, Ken Teraizumi as Ito Hirobumi, Takeshi Iba as Inoue Kaoru, and Christian Burgess as Charles Wirgman.

- A Clash of Cultures (23 September 1992)

- Witness to a Revolution (30 September 1992)

See also

- List of Ambassadors from the United Kingdom to Japan

- Anglo-Japanese relations

- Anglo-Chinese relations

- Asiatic Society of Japan

- Yokohama Archives of History has copies of Satow's diaries and his private letters to his Japanese family.

- Sakoku

- List of Westerners who visited Japan before 1868

- Empress Dowager Cixi

- Chōshū Five

People who knew Satow

Notes

- ↑ The third and subsequent editions of this handbook were titled A Handbook for Travellers in Japan and were cowritten by B. H. Chamberlain and W. B. Mason.

References

- ↑ Nussbaum, "Satow, Ernest Mason", p. 829., p. 829, at Google Books; Nish, Ian. (2004). British Envoys in Japan 1859–1972, pp. 78–88.

- ↑ Satow, Ernest (1921). A Diplomat in Japan (First ICG Muse Edition, 2000 ed.). New York, Tokyo: ICG Muse, Inc. p. 53. ISBN 4-925080-28-8.

- ↑ Griffis, William Elliot (1902). A Maker of the New Orient. New York: Fleming H. Revell Company. p. 165.

- ↑ Asiatic Society of Japan

- 1 2 Todd, Hamish (8 July 2013). "A rare example of Chinese calligraphy by Sir Ernest Satow". Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette, 27 February 1885

- ↑ The first British Ambassador to Japan was appointed in 1905. Before 1905, the senior British diplomat had different titles: (a) Consul-General and Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, which is a rank just below Ambassador.

- ↑ The Semi-official Letters of British Envoy Sir Ernest Satow from Japan and China (1895–1906), edited by Ian Ruxton, 1997, p73

- ↑ The Diaries of Sir Ernest Satow, British Minister in Tokyo (1895–1900), edited by Ian Ruxton, 2003

- ↑ "The Coronation Honours". The Times (36804). London. 26 June 1902. p. 5.

- ↑ "No. 27456". The London Gazette. 22 July 1902. p. 4669.

- ↑ Cullen, Louis M. (2003). A History of Japan, 1582–1941, p. 188.

- ↑ British Museum Collection

- ↑ Nicolson, Harold. (1963). Diplomacy, 3rd ed., p. 148.

- ↑ IPNI. Satow.

Bibliography

- Cullen, Louis M. (2003). A History of Japan, 1582-1941: Internal and External Worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521821551; ISBN 9780521529181; OCLC 50694793

- Nish, Ian. (2004). British Envoys in Japan 1859-1972. Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental. ISBN 9781901903515; OCLC 249167170

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 48943301

- SATOW, Rt Hon. Sir Ernest Mason, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007, accessed 11 Sept 2012

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ernest Mason Satow. |

- Asiatic Society of Japan

- Report of a lecture on Satow in Tokyo 1895-1900 given to the Asiatic Society of Japan

- Ian Ruxton's Ernest Satow page

- UK in Japan, Chronology of Heads of Mission

- Works by Ernest Mason Satow at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ernest Mason Satow at Internet Archive

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by |

Minister Resident and Consul-General to the King of Siam 1885–1888 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by |

Minister Resident at Monte Video, and also Consul-General in the Oriental Republic of the Uruguay 1888–1893 |

Succeeded by Walter Baring |

| Preceded by Sir Charles Euan-Smith |

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary at Tangier, and also Her Majesty's Consul-General in Morocco 1893–1895 |

Succeeded by Sir Arthur Nicolson |

| Preceded by Power Henry Le Poer Trench |

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to His Majesty the Emperor of Japan; and also Consul-General in the Empire of Japan 1895–1900 |

Succeeded by Sir Claude MacDonald |

| Preceded by Sir Claude MacDonald |

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to His Majesty the Emperor of China 1900–1906 |

Succeeded by Sir John Jordan |