Erlitou culture

| |||||||

| Geographical range | Western Henan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age China | ||||||

| Dates | c. 1900 – c. 1500 BC | ||||||

| Type site | Erlitou | ||||||

| Major sites | Erlitou and Dashigu | ||||||

| Preceded by | Longshan culture | ||||||

| Followed by | Erligang culture | ||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 二里頭文化 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 二里头文化 | ||||||

| |||||||

Coordinates: 34°41′35″N 112°41′20″E / 34.693°N 112.689°E

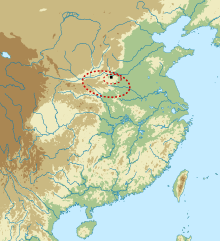

The Erlitou culture was an early Bronze Age urban society and archaeological culture that existed in the Yellow River valley from approximately 1900 to 1500 BC[1] or 1750 to 1530 BC.[2] The culture was named after the site discovered at Erlitou in Yanshi, Henan. The culture was widely spread throughout Henan and Shanxi and later appeared in Shaanxi and Hubei. Chinese archaeologists generally identify the Erlitou culture as the site of the Xia dynasty, but there is no firm evidence, such as writing, to substantiate such a linkage.[3]

Erlitou site

The Erlitou culture may have evolved from the matrix of Longshan culture. Originally centered around Henan and Shanxi Province, the culture spread to Shaanxi and Hubei Province. After the rise of the Erligang culture, the site at Erlitou diminished in size but remained inhabited.[4]

Discovered in 1959 by Xu Xusheng,[5] Erlitou is the largest site associated with the culture, with palace buildings and bronze smelting workshops. Erlitou monopolized the production of ritual bronze vessels, including the earliest recovered dings.[6] The city is on the Yi River, a tributary of the Luo River, which flows into the Yellow River. The city was 2.4 km by 1.9 km; however, because of flood damage only 3 km2 (1.2 sq mi) are left.[4]

Phases

The site is divided into four phases, each of roughly 50 years.

During Phase I, covering 100 ha (250 acres), Erlitou was a rapidly growing regional center with estimated population of several thousand,[7] but not yet an urban civilization or capital.[8]

Urbanization began in Phase II, expanding to 300 ha (740 acres) with a population around 11,000.[7] A palace area of 12 ha (30 acres) was demarcated by four roads. It contained the 150x50 m Palace 3, composed of three courtyards along a 150-meter axis, and Palace 5.[4] A bronze foundry was established to the south of the palatial complex that was controlled by the elite who lived in palaces.[9]

The city reached its peak in Phase III, and may have had a population of around 24,000.[8] The palatial complex was surrounded by a 2-meter thick rammed earth wall and Palaces 1, 7, 8, 9 were built. The earthwork volume of rammed earth for the base of largest Palace 1 is 20,000 m³ at least.[10] Palaces 3 and 5 were abandoned and replaced by 4200 m2 Palace 2 and Palace 4.[11]

In Phase IV the population decreased to around 20,000, but building continued. Palace 6 was built as an extension of Palace 2, and Palaces 10 and 11 were built. Phase IV overlaps with the Lower phase of the Erligang culture (1600–1450 BC). Around 1600 to 1560 BC, about 6 km northeast of Erlitou, Eligang cultural walled city was built at Yanshi,[11] which coincide with an increase in production of arrowheads at Erlitou.[7] This situation might indicate that the Yanshi City was competing for power and dominance with Erlitou.[7]

Production of bronzes and other elite goods ceased at the end of Phase IV, at the same time as the Erligang city of Zhengzhou was established 85 km (53 mi) to the east. There is no evidence of destruction by fire or war, but during the Upper Erligang phase (1450–1300 BC) all the palaces were abandoned, and Erlitou was reduced to a village of 30 ha (74 acres).[11]

Relation to traditional accounts

A major goal of archaeology in China has been the search for the capitals of the Xia and Shang dynasties described in traditional accounts as inhabiting the Yellow River valley.[12] These originally oral traditions were recorded much later in histories such as the Bamboo Annals (c. 300 BC) and the Records of the Grand Historian (1st century BC), and their historicity, particularly regarding the Xia, is an area of debate for the Doubting Antiquity School of Chinese history.[13] The discovery of writing in the form of oracle bones at Yinxu in Anyang definitively established the site as the last capital of the Shang, but such evidence is unavailable for earlier sites.[14]

When Xu Xusheng first discovered Erlitou, he suggested that it was Bo, the first capital of the Shang under King Tang in the traditional account.[15] Since the late 1970s speculation among Chinese achaeologists has focused on its relationship to the Xia. The traditional account of the overthrow of the Xia by the Shang has been identified with the ends of each of the four phases of the site by different authors. The Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project identified all four phases of Erlitou as Xia, and the construction of the Yanshi walled city as the founding of the Shang.[16] Other scholars, particularly outside China, point to the lack of any firm evidence for such an identification, and argue that the historiographical focus of Chinese archaeology is unduly limiting.[17]

Archaeological evidence of a large outburst flood that destroyed the Lajia site on the upper reaches of the Yellow River has been dated to about 1920 BC. This date is shortly before the rise of the Erlitou culture in the middle Yellow River valley and the Yueshi culture in Shandong, following the decline of the Longshan culture in the North China Plain. The authors suggest that this flood may have been the basis for the later myth, and contributed to the transition of cultures. They further argue that the timing is further evidence for the identification of the Xia with the Erlitou culture.[18] No evidence of contemporaneous widespread flooding in the North China Plain is yet known; if it is found in the future, this would strengthen the persuasiveness of the paper.[19]

See also

- List of Neolithic cultures of China

- Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors

- Women in ancient and imperial China

References

- ↑ Allan 2007; Liu & Xu 2007, p. 886.

- ↑ Zhang et al. 2014, p. 206.

- ↑ Allan 2007; Liu 2004; Liu & Xu 2007.

- 1 2 3 Li 2003.

- ↑ Liu & Chen 2012, p. 259.

- ↑ Liu 2004, p. 231.

- 1 2 3 4 Liu 2006, p. 184.

- 1 2 Liu 2004, p. 229.

- ↑ Liu 2004, pp. 230–231.

- ↑ "二里头:华夏王朝文明的开端". 寻根. 3.

- 1 2 3 Liu & Xu 2007.

- ↑ Liu & Chen 2012, p. 256.

- ↑ Liu & Xu 2007, p. 897.

- ↑ Liu & Chen 2012, pp. 256–258.

- ↑ Liu & Xu 2007, p. 894.

- ↑ Lee 2002.

- ↑ Liu & Chen 2012, p. 258.

- ↑ Wu, Qinglong; Zhao, Zhijun; Liu, Li; Granger, Darryl E.; Wang, Hui; Cohen, David J.; Wu, Xiaohong; Ye, Maolin; Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Lu, Bin; Zhang, Jin; Zhang, Peizhen; Yuan, Daoyang; Qi, Wuyun; Cai, Linhai; Bai, Shibiao (2016). "Outburst flood at 1920 BCE supports historicity of China’s Great Flood and the Xia dynasty". Science. 353 (6299): 579–582. PMID 27493183. doi:10.1126/science.aaf0842.

- ↑ Normile, Dennis (2016). "Massive flood may have led to China's earliest empire". News. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

Works cited

- Allan, Sarah (2007). "Erlitou and the Formation of Chinese Civilization: Toward a New Paradigm". The Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 66 (2): 461–496. doi:10.1017/S002191180700054X.

- Lee, Yun Kuen (2002). "Building the chronology of early Chinese history". Asian Perspectives. 41 (1): 15–42. doi:10.1353/asi.2002.0006.

- Li, Jinhui (November 10, 2003). "Stunning Capital of Xia Dynasty Unearthed". China Through a Lens. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Liu, Li (2004). The Chinese Neolithic: trajectories to early states. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81184-2.

- ——— (2006). "Urbanization in China: Erlitou and its hinterland". In Storey, Glenn. Urbanism in the Preindustrial World. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 161–189. ISBN 978-0-8173-5246-2.

- Liu, Li; Xu, Hong (2007). "Rethinking Erlitou: legend, history and Chinese archaeology". Antiquity. 81 (314): 886–901. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00095983.

- Liu, Li; Chen, Xingcan (2012). The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64310-8.

- Zhang, Xuelian; Qiu, Shihua; Cai, Lianzhen; Bo, Guancheng; Wang, Jinxia; Zhong, Jian (2014). Translated by Zhang, Xuelian; Lee, Yun Kuen. "Establishing and refining the archaeological chronologies of Xinzhai, Erlitou and Erligang cultures". Chinese Archaeology. 8 (1): 197–210. Original article in Kaogu 2007.8: 74–84.

Further reading

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006) [1992]. China: A New History (2nd enlarged ed.). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01828-1.

- Fong, Wen, ed. (1980). The great bronze age of China: an exhibition from the People's Republic of China. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87099-226-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erlitou culture. |

- Bronze Age China, The Golden Age of Chinese Archaeology: Exhibition brochure, National Gallery of Art.

- Erlitou Site, Erlitou Site, chinaculture.org

- Erlitou Site, Erlitou Site - Relics of the Capital of the Xia Dynasty, Cultural China