Erard of Brienne-Ramerupt

Érard de Brienne (c. 1170 † 1246) was a French nobleman. He was lord of Ramerupt and of Venizy, and also a pretender to the county of Champagne as an instigator of the Champagne War of Succession. He was a son of André of Brienne and of Alix of Vénizy.

Early life

He was born in Ramerupt, Aube, Champagne, France.[3]

A social-climber from a minor branch of the Brienne family, Erard actually held no lands in Brienne and had little just cause to appropriate the name "of Brienne" for himself. His uncle Erard II of Brienne had indeed ruled as count of Brienne. Andre, the brother of Erard II, was the father of Erard of Brienne-Ramerupt. Erard was actually lord of Ramerupt, which wasn't very impressive compared to the holdings of the more senior branches of the Brienne family. Within his own letters, Erard thus tried to enhance his prestige by consistently referring to himself as "Erard of Brienne" and not even mentioning Ramerupt. The name "Erard of Brienne-Ramerupt" is retroactively applied by historians for the sake of clarity.[4]

While Andre was the brother of Count Erard of Brienne, his second son - and thus Erard of Brienne-Ramerupt's cousin - was the famous crusader knight John of Brienne (1170-1237), who in 1210 wed the heiress Maria of Jerusalem to become the nominal King of Jerusalem by marriage (albeit, the crusaders had lost control of the city of Jerusalem itself by this point). Perhaps seeking to emulate the success of his uncle, who found great prestige traveling to the east and marrying a powerful heiress, thus in June 1213 he left Champagne for the Latin East with the stated intention of marrying Philippa of Champagne, the younger half-sister of Maria of Jerusalem.[5]

The War of Succession of Champagne

The line of succession of the counts of Champagne had become complicated in the current generation. Count Henry I had two sons with Marie of Champagne, Henry II and Theobald III. Henry II succeeded as count on his father's death, but left France within a few years to fight in the Third Crusade. Before he left in 1190, Henry II had his barons swear that should he never return, his younger brother Theobald III was his designated heir. The problem was that Henry II never returned from the Latin East, but instead chose to marry the then-heiress to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Queen Isabella I - eight days after the assassination of her husband Conrad of Montferrat, which Henry II might possibly have had a hand in orchestrating. Moreover, Isabella I was already visibly pregnant with Conrad's child - Maria of Jerusalem, who later married John of Brienne - thus the marriage was considered scandalous by many. Henry II fathered two daughters with Maria, Queen Alice of Cyprus and Philippa.[6]

Henry II died in a fall from a balcony seven years later in 1197. Since 1190, Henry II's mother Marie had been ruling Champagne as regent, and continued to do so past Henry II's death on behalf of her younger son Theobald III until her own death the following year in 1198. Technically, Henry II's young daughters were the rightful heirs to Champagne in line of succession. However, their family made no attempt to press the claim and return to Champagne. Theobald III, in contrast, was living in Champagne and already eighteen years old (slightly short of the unusually late age of majority in Champagne at twenty-one years old). Particularly, the barons of Champagne had sworn to recognize Theobald III as Henry II's heir should he not return to Champagne, never considering that Henry II would choose to stay in the Latin East and father children there. Thus when Marie died in 1198, Theobald III succeeded her as count of Champagne, with the mediation and approval of King Philip II Augustus, to whom Theobald III officially swore homage. Theobald III died of a sudden illness only three years later in May 1201, but he left behind his young and heavily pregnant wife Blanche of Navarre. Blanche already had an infant daughter with Theobald III, but quickly traveled to Philip II's court to implore him to recognize her unborn child's claim if it was a son, citing the agreements Henry II's barons had sworn to recognize Theobald III as his heir should he not return. Blanche formally performed the homage ceremony with Philip II, and a week later indeed gave birth to a son, Theobald IV. Given that local custom in Champagne stipulated that the age of majority was twenty-one (unusually late compared to other regions of France), all knew that Champagne was now in the vulnerable position of facing a twenty-one-year-long regency under Blanche, under a young and inexperienced Basque-speaking foreign princess. Blanche and Theobald IV were already in a vulnerable position, but it was known that Henry II left daughters behind in the Latin East who were technically ahead of Theobald IV in the rightful line of succession.

Perhaps inspired by his uncle John's marriage to Maria of Jerusalem, in June 1213 Erard announced his intention to travel to the Latin East to marry Maria's younger step-sister Philippa. He returned to Champagne with his new bride in January 1216.[7] Armed clashes soon broke out, and the War of Succession of Champagne began.

King Philip II imposed a truce in April 1216 to put a stop to the fighting, and held a court at Melun in July 1216 to hear Edard and Philippa's case. Unfortunately for Erard, the court ruled that because Theobald III had already done homage for Champagne to the king for several years, yet Philippa and her family never challenged his succession in all that time, Henry II's daughters could no longer make a claim for the inheritance. Blanche again presented the signed agreements of Henry II's barons which swore that Theobald III was to be his heir if he never returned from the crusade. Unsatisfied, Erard returned to open rebellion in spring 1217. Erard gathered to himself a large number of barons from the fringes of Champagne or from old and powerful aristocratic families, who were not pleased with the increasing efforts of Theobald III and Blanche to bring them all under centralized control. Most of Erard and Philippa's supports came from the fringes of Champagne, along the southern and eastern borders, away from the core territories of "Champagne and Brie" in the west. One of Erard's major supporters was Simon of Joinville, hereditary seneschal of Champagne and leader of one of the most powerful noble families in the county. Further, Erard allied with Theobald I, Duke of Lorraine, significantly bolstering the rebel faction.

By 1218, however, the tide had turned, as Blanche secured papal excommunications against the rebel lords, and gained the support of the neighboring duke of Burgundy and count of Bar. Further, Blanche allied with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II to counterbalance Duke Theobald I of Lorraine. By May 1218 Blanche and her army rode with Frederick II's forces to Lorraine's capital of Nancy and burned it to the ground. By June 1218, the rebellion had largely collapsed and individual lords began to make their own separate peaces. Erard and Philippa established a truce agreement in July 1218, which ultimately lasted the rest of Blanche's regency until 1222, during which time other rebel lords continued to haggle for better peace terms.

Blanche offered peace on generous terms to Erard and Philippa, wanting to end the challenge to her son's rule as quickly as possible. Erard received a surprisingly large payment of 4,000 livres, with a lifetime rent of 1,200 livres.

Only after the war ended, when hope of becoming count of Champagne was lost, did Erard stop the charade of presenting himself as "Erard of Brienne". Instead, after 1222, he would specify in his letters that he was "Erard of Brienne, lord of Ramerupt".

Later life

Despite losing the war, on the whole Erard did quite well for himself. He had started out as a grasper from a minor branch of the Brienne family, clinging to a name he didn't technically have the right to use because it enhanced his social prestige. The massive payoff that Blanche gave Erard in the peace agreement that ended the war, however, propelled him to a place alongside the highest level of regional barons. Erard used his newfound wealth to buy up lands surrounding his own, so that he was able to cobble together his own larger barony. By 1227, he even bought up the other half-share of Ramerupt - he had only owned a half-share of his own castle up to this point - uniting it under his sole possession.[8]

Erard did not intervene against Theobald IV during the difficult invasion of other northern barons of France in 1229, because anticipating that Erard might try to challenge him again, Theobald IV bought him off with a 200 livre fief, and in return had to swear to surrender his castles of Ramerupt and Venizy until the invasion was over.[9]

Erard died at roughly the age of sixty in 1243. All that he had striven to achieve for himself and his children, however, evaporated within only a few years. Both of his sons died on the Seventh Crusade in 1250, and his wife Philippa died that same year. Erard had six daughters, one of whom had predeceased him without issue and another who became a nun. Ramerupt was subsequently divided into quarters between the remaining four daughters, whose husbands absorbed the lands into their own separate lordships.

Marriage and issue

Erad married Philippa of Champagne, they had the following children:

- Henri de Brienne (killed in battle at Mansurah 8 February 1250), Seigneur of Ramerupt and de Vénisy, married Marguerite de Salins by whom he had two sons.

- Erard de Brienne (killed in battle, February 1250), married Mathilde by whom he had one daughter.

- Marie de Brienne (1215[10]- c.1251), married firstly Gaucher, Sire de Nanteuil-la Fosse, by whom she had three children; she married secondly Hughes II, Sire de Conflans, by whom she had one son.

- Marguerite de Brienne (died 1275), married Dirk Van Beveren, Burggraf of Dixmuiden, by whom she had issue. She became a nun after her husband's death.

- Heloise de Brienne

- Isabeau de Brienne (died 1274/1277), married firstly Henri V, Count of Grandpré, by whom she had three children; she married secondly Jean de Picquigny, by whom she had one daughter. Isabeau was the ancestress of Louis I, Count of Flanders.

- Jeanne de Brienne, Dame de Séans-en-Othe, married before 1250 Mathieu III, Sire de Montmorency, by whom she had five children.

- Sibylle de Brienne, Abbess of Ramerupt

- Alix de Brienne

Philippa died on 20 December 1250, a little more than six years after her husband. She was aged about fifty-three.

References

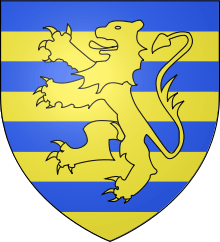

- ↑ Armorial de Rietstap

- ↑ EarlyBlazon

- ↑ Erard DE BRIENNE

- ↑ Theodore Evergates, Aristocracy in the County of Champagne (2007), 135.

- ↑ Theodore Evergates, Aristocracy in the County of Champagne (2007), 241.

- ↑ Theodore Evergates, Aristocracy in the County of Champagne (2007), 241.

- ↑ Theodore Evergates, Aristocracy in the County of Champagne (2007), 241.

- ↑ Theodore Evergates, Aristocracy in the County of Champagne (2007), 241.

- ↑ Theodore Evergates, Aristocracy in the County of Champagne (2007), 241.

- ↑ Philippa de Champagne

Sources

- Evergates, Theodore. The Aristocracy in the County of Champagne, 1100-1300. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press: 2007.