Entamoeba

| Entamoeba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Amoebozoa |

| Class: | Archamoebae |

| Family: | Entamoebidae |

| Genus: | Entamoeba Casagrandi & Barbagallo, 1897 |

| Species | |

|

E. bangladeshi | |

Entamoeba is a genus of Amoebozoa found as internal parasites or commensals of animals.

In 1875, Fedor Lösch described the first proven case of amoebic dysentery in St. Petersburg, Russia. He referred to the amoeba he observed microscopically as 'Amoeba coli'; however it is not clear whether he was using this as a descriptive term or intended it as a formal taxonomic name.[1] The genus Entamoeba was defined by Casagrandi and Barbagallo for the species Entamoeba coli, which is known to be a commensal organism.[2] Lösch's organism was renamed Entamoeba histolytica by Fritz Schaudinn in 1903; he later died, in 1906, from a self-inflicted infection when studying this amoeba. For a time during the first half of the 20th century the entire genus Entamoeba was transferred to Endamoeba, a genus of amoebas infecting invertebrates about which little is known. This move was reversed by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in the late 1950s, and Entamoeba has stayed 'stable' ever since.

Species

Several species are found in humans and animals. Entamoeba histolytica is the pathogen responsible for invasive 'amoebiasis' (which includes amoebic dysentery and amoebic liver abscesses). Others such as Entamoeba coli (not to be confused with Escherichia coli) and Entamoeba dispar[3] are harmless. With the exception of Entamoeba gingivalis, which lives in the mouth, and E. moshkovskii, which is frequently isolated from river and lake sediments, all Entamoeba species are found in the intestines of the animals they infect. Entamoeba invadens is a species that can cause a disease similar to E. histolytica but in reptiles. In contrast to other species, E. invadens forms cysts in vitro in the absence of bacteria and is used as a model system to study this aspect of the life cycle. Many other species of Entamoeba have been described and it is likely that many others remain to be found.

Structure

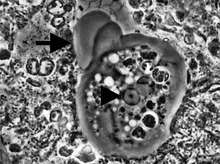

Entamoeba cells are small, with a single nucleus and typically a single lobose pseudopod taking the form of a clear anterior bulge. They have a simple life cycle. The trophozoite (feeding-dividing form) is approximately 10-20 μm in diameter and feeds primarily on bacteria. It divides by simple binary fission to form two smaller daughter cells. Almost all species form cysts, the stage involved in transmission (the exception is Entamoeba gingivalis). Depending on the species, these can have one, four or eight nuclei and are variable in size; these characteristics help in species identification.

Classification

Entamoeba belongs to the Archamoebae, which like many other anaerobic eukaryotes lack mitochondria. This group also includes Endolimax and Iodamoeba, which also live in animal intestines and are similar in appearance to Entamoeba, although this may partly be due to convergence. Also in this group are the free-living amoebo-flagellates of the genus Mastigamoeba and related genera.[4] Certain other genera of symbiotic amoebae, such as Endamoeba, might prove to be synonyms of Entamoeba but this is still unclear.

Culture

Fission

Studying Entamoeba invadens, David Biron of the Weizmann Institute of Science and coworkers found that about one third of the cells are unable to separate unaided and recruit a neighboring amoeba (dubbed the "midwife") to complete the fission.[5] He writes:

- When an amoeba divides, the two daughter cells stay attached by a tubular tether which remains intact unless mechanically severed. If called upon, the neighbouring amoeba midwife travels up to 200 μm towards the dividing amoeba, usually advancing in a straight trajectory with an average velocity of about 0.5 μm/s. The midwife then proceeds to rupture the connection, after which all three amoebae move on.

They also reported a similar behavior in Dictyostelium.[6]

Since E. histolytica does not form cysts in the absence of bacteria, E. invadens has become used as a model for encystation studies as it will form cysts under axenic growth conditions, which simplifies analysis. After inducing encystation in E. invadens, DNA replication increases initially and then slows down. On completion of encystation, predominantly tetra-nucleate cysts are formed along with some uni-, bi- and tri-nucleate cysts.[7]

Differentiation and cell biology

Uni-nucleated trophozoites convert into cysts in a process called encystation. The number of nuclei in the cyst varies from 1 to 8 among species and is one of the characteristics used to tell species apart. Of the species already mentioned, Entamoeba coli forms cysts with 8 nuclei while the others form tetra-nucleated cysts. Since E. histolytica does not form cysts in vitro in the absence of bacteria, it is not possible to study the differentiation process in detail in that species. Instead the differentiation process is studied using E. invadens, a reptilian parasite that causes a very similar disease to E. histolytica and which can be induced to encyst in vitro. Until recently there was no genetic transfection vector available for this organism and detailed study at the cellular level was not possible. However, recently a transfection vector was developed and the transfection conditions for E. invadens were optimised which should enhance the research possibilities at the molecular level of the differentiation process.[8][9]

Meiosis

In sexually reproducing eukaryotes, homologous recombination (HR) ordinarily occurs during meiosis. The meiosis-specific recombinase, Dmc1, is required for efficient meiotic HR, and Dmc1 is expressed in E. histolytica.[10] The purified Dmc1 from E. histolytica forms presynaptic filaments and catalyzes ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and DNA strand exchange over at least several thousand base pairs.[10] The DNA pairing and strand exchange reactions are enhanced by the eukaryotic meiosis-specific recombination accessory factor (heterodimer) Hop2-Mnd1.[10] These processes are central to meiotic recombination, suggesting that E. histolytica undergoes meiosis.[10]

Studies of E. invadens found that, during the conversion from the tetraploid uninucleate trophozoite to the tetranucleate cyst, homologous recombination is enhanced.[11] Expression of genes with functions related to the major steps of meiotic recombination also increased during encystations.[11] These findings in E. invadens, combined with evidence from studies of E. histolytica indicate the presence of meiosis in the Entamoeba.

References

- ↑ Lösch, F (1875). "Massenhafte Entwickelung von Amöben im Dickdarm". Virchow's Archiv. 65 (2): 196–211. doi:10.1007/bf02028799.

- ↑

- Casagrandi, O.; Barbagallo, P. (1895). "Ricerche biologiche e cliniche sull' Amoeba coli (Lösch). (Nota preliminare)". Bollettino delle sedute della Accademia Gioenia di Scienze Naturali in Catania. 39: 4.

- ↑ Diamond LS, Clark CG (1993). "A redescription of Entamoeba histolytica Schaudinn, 1903 (emended Walker, 1911) separating it from Entamoeba dispar Brumpt, 1925". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 40 (3): 340–344. PMID 8508172. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04926.x.

- ↑ Stensvold CR, Lebbad M, Clark CG (January 2012). "Last of the human protists: the phylogeny and genetic diversity of Iodamoeba.". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (1): 39–42. PMID 21940643. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr238.

- ↑ Biron D, Libros P, Sagi D, Mirelman D, Moses E (2001). "Asexual reproduction: 'Midwives' assist dividing amoebae". Nature. 410 (6827): 430. PMID 11260701. doi:10.1038/35068628.

- ↑ Nagasaki, A and Uyeda, T., Q., P.; Chemotaxis-Mediated Scission Contributes to Efficient Cytokinesis in Dictyostelium, Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton; Vol. 65; Issue 11; Article first published online: 7 AUG 2008

- ↑ Singh N, Bhattacharya S, Paul J (2010). "Entamoeba invadens: Dynamics of DNA synthesis during differentiation from trophozoite to cyst". Experimental Parasitology. 127 (2): 329–33. PMID 20727884. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2010.08.013.

- ↑ Singh, Nishant; Ojha, Sandeep; Bhattacharya, Alok; Bhattacharya, Sudha (2012). "Establishment of a transient transfection system and expression of firefly luciferase in Entamoeba invadens". Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 183 (1): 90– 93. PMID 22321531. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.01.003.

- ↑ Singh, Nishant; Ojha, Sandeep; Bhattacharya, Alok; Bhattacharya, Sudha (2012). "Stable transfection and continuous expression of heterologous genes in Entamoeba invadens". Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 184 (1): 9–12. PMID 22426570. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.02.012.

- 1 2 3 4 Kelso AA, Say AF, Sharma D, Ledford LL, Turchick A, Saski CA, King AV, Attaway CC, Temesvari LA, Sehorn MG (2015). "Entamoeba histolytica Dmc1 Catalyzes Homologous DNA Pairing and Strand Exchange That Is Stimulated by Calcium and Hop2-Mnd1". PLoS ONE. 10 (9): e0139399. PMC 4589404

. PMID 26422142. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139399.

. PMID 26422142. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139399. - 1 2 Singh N, Bhattacharya A, Bhattacharya S (2013). "Homologous recombination occurs in Entamoeba and is enhanced during growth stress and stage conversion". PLoS ONE. 8 (9): e74465. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...874465S. PMC 3787063

. PMID 24098652. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074465.

. PMID 24098652. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074465.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Entamoeba |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Entamoeba. |