Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa

| Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa 1845 Madrid, Spain |

| Died |

1922 Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | politician |

| Known for | archaeologist, politician |

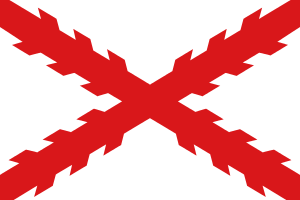

| Political party | Carlism |

Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa, 17th Marquis of Cerralbo (1845 – 1922), was a Spanish archaeologist and a Carlist politician.

Family and youth

Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa came from the aristocratic family for centuries residing in the Salamanca province;[1] his ancestors can be traced back to the 14th century, and it was in 1533 when his forefather was named marquis by Carlos I.[2] His father, Francisco de Asís de Aguilera y Becerril, was the founder and director of the Gimnasio Real de Madrid (Casón del Buen Retiro) and became known as a promoter of physical exercises, supported with a number of machines he invented himself.[3] Married to María Luisa de Gamboa y López de León, the couple had 13 children.[4]

Enrique was first educated at the Madrid Colegio de las Escuelas Pías de San Fernando, later on to study Philosophy and Letters and Law at the Universidad Central.[5] With the death of his father in 1867, Enrique as the oldest living son acquired the conde de Villalobos title,[6] which ensured his place in the middle-range aristocracy and a comfortable financial status. His position changed dramatically in the early 1870s, when, following the childless death of his two paternal uncles and death of his paternal grandfather, José de Aguilera y Contreras, Enrique became the most senior male in line.[7] He inherited the marquesado de Cerralbo, along with many other aristocratic titles,[8] some of them ceded to his brothers.[9] By virtue of the marquesado de Cerralbo and condado de Alcudia, he became a double grandee of Spain. Enrique inherited part of his grandfather’s enormous wealth, including a number of estates in southern Leon,[10] villa de Cerralbo and the San Boal palace in Salamanca.[11] The heritage elevated Enrique into the highest ranks of the Spanish nobility and ensured lifetime opulence. He later multiplied his wealth by marriage, cautious investments on the stock exchange and in the railway business, and by inheriting part of the fortune of the marqués de Monroy,[12] which allowed him to purchase new estates in Madrid, Santa María de Huerta and in Monroy.[13]

In 1871, Enrique married the mother of his university colleague, Manuela Inocencia Serrano y Cerver from Valencia,[14] thirty years his senior and widow of the military and senator Antonio del Valle y Angelín;[15] she brought into the family the children from her previous marriage.[16] Immediately afterwards, the couple travelled extensively[17] and started construction of the family residence in Madrid. In 1893, the family moved into the freshly-completed building at calle Ventura Rodríguez, designed in eclectic style[18] by renowned architects and from the outset intended to be also an art gallery, very much like the private pinacotecas seen across Europe.[19] The building – usually referred to as a palace – served later also as a prestigious venue of social meetings, reported the day after by the Madrid press,[20] and a location for political assemblies. The couple had no issue.[21]

Early Carlist years

Though his paternal ancestors remained loyal to the Isabelinos, it was Enrique’s mother who influenced him towards Carlism,[22] the leaning reinforced during the university years.[23] According to himself always a Carlist,[24] he joined the movement in 1869,[25] the same year founding also the affiliated Juventud Catolica.[26] As conde de Villalobos he unsuccessfully ran for the Cortes in 1871 from Ciudad Rodrigo,[27] but obtained the mandate in the successive elections of 1872 from Ledesma.[28] His service lasted only 2 months, since before the planned insurgency the claimant ordered his deputies to resign.[29] There is no evidence that Enrique de Aguilera took part in the Third Carlist War and that he was exiled, though the issue is not entirely clear.[30] In 1876 in Paris, already as marqués, he was introduced to Carlos VII.[31] The two developed cordial relationship bordering personal friendship;[32] de Cerralbo turned out - along Solferino - one of two grandees who sided with Carlism[33] and automatically became one of its most distinguished figures.[34]

Within Carlism de Cerralbo tried to champion the religious cause,[35] but he proved no match for Cándido Nocedal.[36] The conflict grew when Nocedal was nominated Jefe Delegado in 1879, Nocedal opting for immovilismo and Cerralbo for aperturismo.[37] Another issue was Nocedal’s drive to emphasize the Catholic features at the expense of dynastical ones.[38] As Carlos VII grew uncomfortable about power shifting away from his hands and as Nocedal’s leadership caused grumblings among many Carlists,[39] Cerralbo engaged in few attempts to outmaneuver him,[40] but since they remained fruitless,[41] he pondered upon withdrawing from politics.[42]

When Cándido Nocedal died in 1885 Cerralbo was widely rumored to succeed him,[43] but Carlos VII decided to lead the movement personally. Quoting health reasons Cerralbo for some time distanced himself from Carlist politics, marked by further conflict between Ramón Nocedal and the pretender.[44] By virtue of his grandeza he entered the Senate in 1885,[45] where he was the only Carlist.[46] In 1886 Cerralbo headed a makeshift Junta co-coordinating the Carlist electoral effort,[47] though structures of the movement were increasingly paralyzed by conflict until the Nocedalistas were expelled in 1888.[48] The same year Carlos VII decided to counter their El Siglo Futuro by ordering de Cerralbo to create the official Carlist daily[49] El Correo Español,[50] which commenced his lifelong friendship with Juan Vázquez de Mella.[51] De Cerralbo engaged in many other Carlist cultural initiatives.[52] As royal representative he travelled across Spain in 1889-1890,[53] a novelty in terms of mass mobilization; during some of these visits he was assaulted by the Republicans.[54] Eventually, following other royal favors,[55] in 1890 Cerralbo was nominated Jefe Delegado,[56] receiving the claimant’s political carte blanche.[57]

First tenure

Cerralbo’s leadership was marked by conciliatory course towards political groupings of the Right,[58] with intransigence reserved only for the Integrists, labeled traitors and rebels.[59] He shifted focus from conspiracy to parliamentary activity,[60] though the results obtained in elections of 1891[61] and 1893[62] were rather poor. Apparently aware of the forthcoming mass culture age, he worked to develop the Carlist propaganda machinery, introducing first attempts to co-ordinate the Carlist press,[63] but including also a network of libraries and publishing houses,[64] combined with other means of public activity like lectures, feasts,[65] erecting monuments, setting up prizes and creating honorary member lists.[66] A novelty in his propaganda was the systematic usage of images, as he arranged for portraits and photographs of Carlist leaders (including himself) to be printed in countless editions.[67] He also tried to build economic foundations of the movement, issuing shares of various Carlist-controlled institutions.[68]

Perhaps the most important of de Cerralbo’s achievements was building a nationwide Carlist organization, which transformed the movement from a 19th-century “party” of loosely organized leaders with their local following into a formal institutionalized structure. During his tenure there were some 2000 juntas and 300 circulos created.[69] Though some of them existed only on paper and the organization was limited chiefly to Northern and Eastern Spain,[70] Carlism became the most modern political party of the time,[71] as two major partidos de turno remained rather electoral alliances, dormant between the polling periods. The transformation of Traditionalism under de Cerralbo led many to label the movement “carlismo nuevo”.[72]

De Cerralbo, though not an ideologue himself, presided over the works on Acta de Loredán, the Carlist doctrinal statement released early 1897.[73] The document confirmed the ultraconservative profile of Carlism and confirmed its commitment to religion, dynasty, and decentralized state, the relative novelties having been an effort to accommodate the social teaching of the Church[74] and to lure back the Integrists by highlighting the principle of Catholic unity.[75]

As the crisis in Cuba mounted, the liberal press was repeatedly warning against a new Carlist insurgency, allegations usually refuted by Correo Español.[76] Small Carlist groups indeed resolved to violence and de Cerralbo tried to prevent the phenomenon.[77] The pretender seemed decided not to weaken the country while at war with the United States, but the situation changed following the disastrous peace of 1898, as Carlos VII made some moves interpreted as preparation to another Carlist war.[78] Cerralbo, widely considered the leader of the pigeons[79] and confronted by the hawks like Llorens,[80] was rumored to be dismissed soon.[81] Quoting health reasons he left Spain and distanced himself from the conflict, finally handing his resignation as Jefe Delegado in late 1899.[82] The notice was accepted by Carlos VII, who nominated Matías Barrio y Mier as the new political leader.[83]

Break in leadership

.jpg)

De Cerralbo left Spain mid-1900[84] and was absent during La Octubrada, the failed Carlist insurrection in Badalona of October 1900.[85] Surprised by the coup he condemned it as premature, though in principle he did not exclude a violent action.[86] He did not withdraw from the Senate.[87] It is not clear whether de Cerralbo, like many Carlist leaders, was expulsed from Spain,[88] the only measure confirmed two police search raids on his Madrid residence.[89] He returned early 1901 and resumed his duties in the Senate.[90] His relationship with Carlos VII remained correct, but the two were getting more and more apart, especially following dismissal of conde de Melgar (Cerralbo’s friend) as the claimant’s political secretary, and the growing influence of his second wife, Berthe de Rohan.[91] Cerralbo remained loyal to the pretender and his Jefe Delegado Barrio y Mier, taking part in Carlist initiatives and feasts of Madrid. He was also ready to enter Junta Central, the collective governing body designed but eventually abandoned in 1903.[92] He forged a friendly relationship with the son of Carlos VII, Don Jaime, as the two shared historical and archaeological interests.[93] Following the period of poor health and limited public activity, in mid-1900s de Cerralbo increased his engagements becoming head of the Carlist parliamentary minority.[94] When Matías Barrio died in 1909 de Cerralbo was widely rumored to return to the Jefe Delegado position,[95] but as one of his last political decisions Carlos VII nominated Bartolomé Feliú Perez instead, the move welcomed by some and protested by the others.[96]

Second Tenure

The 1909 death of Carlos VII turned political fortunes of de Cerralbo, who consulted by the new claimant Don Jaime advised that as a Carlist king he should adopt the name of Jaime III.[97] Many distinguished Carlists[98] pressed the pretender to dismiss Feliú and re-appoint Cerralbo.[99] The claimant bowed to the pressure in 1912,[100] creating a collective governing body, Junta Superior Central Tradicionalista, with de Cerralbo as its president.[101] A number of authors claim that de Cerralbo was the de facto Jefe Delegado[102] and the press, like many contemporaries, presented him as such.[103] The competitive theory maintains that de Mella, sensing the forthcoming clash with Don Jaime, assumed that aging and sick Cerralbo, his old-time friend, would be easier to manipulate; some claim that following the appointment it was actually de Mella who was running the party.[104]

De Cerralbo returned to his conciliatory policy towards other conservative parties;[105] he also resumed tours across Spain, and re-organized the party by creating 10 commissions.[106] A novelty in party tactics was an attempt to emphasize its public presence by organizing romerías, aplecs and pilgrimages, also abroad.[107] It was during his second tenure that Requete was born, shaped by Llorens as the paramilitary organization.[108] De Cerralbo remained perfectly loyal to the claimant, though Don Jaime was increasingly uneasy about the growing position of de Mella, which led to clashes related to management of Correo Español.[109]

As the European war broke out in 1914 de Cerralbo favored Spanish neutrality, though he sympathized with the Central Powers,[110] considering their monarchical model closer to Carlist ideal and traditionally opposing Great Britain, viewed as arch-enemy of Spain.[111] He had to face a hard task of maintaining Carlist unity, as some in the movement, including the claimant himself, favored the Allies.[112] Another dispute de Cerralbo had to defuse took place in Catalonia and was related to politics towards local nationalism, resulting in Miquel Junyent i Rovira appointed the local jefe.[113] The most difficult issue, however, was the growing conflict between de Mella and Jaime III. Unable to sort out the loyalty dilemma, plagued by health problems and embittered by attacks of his former friends,[114] in the spring of 1918 de Cerralbo quoted health reasons and resigned.[115]

When the Mellistas broke away in 1919, De Cerralbo, already outside the Carlist leadership, did not take a clear stand; instead, he withdrew from politics altogether. Though Don Jaime refrained from open criticism, privately he did not spare de Cerralbo harsh words, repeated in public by other prominent Jaimistas; it was de Mella who spoke in his defense.[116] Cerralbo did not take part in the 1919 Magna Junta de Biarritz, a congregation entrusted with marking the future direction of Carlism.[117] His last public nomination was appointment to alcalde of the Madrid district of Argüelles in 1920.[118]

Archaeologist and historian

.jpg)

Since his university days de Cerralbo has developed keen interest in culture and history; his first encounter with archaeology took place in the Madrid site of Ciempozuelos in 1895.[119] He started to collect objects retrieved from various demolitions and organized archeological excavations himself: the first ones were those in upper Jalón valley, commenced in 1908.[120] His key success was discovery of the Celtiberian site of Arcóbriga, listed as Arcobrigensis in the Roman sources and sought by generations from the 16th century; based on multi-faceted analysis[121] Cerralbo correctly narrowed the search area and discovered the site, where excavations were to continue for tens of years to come.[122] In 1909, following numerous notes about odd findings, he commenced excavations in Torralba del Moral and Ambrona, continued until 1916, at that time considered the most ancient human settling discovered so far in Europe.[123] El hombre fossil by Hugo Obermaier (1916), a paleontological reference book for generations, was partially based on de Cerralbo’s findings. Remained a promoter, sponsor, director and assessor on many other sites.[124]

Though de Cerralbo’s excavation methodology is now considered outdated,[125] he introduced new techniques like photography both on site and in laboratory[126] or complex indexing methods.[127] He co-operated with specialists like geologists, cartoonists, historians, engineers, photographers or paleontologists, sharing discoveries on many scientific fora.[128] Cerralbo became member of many scientific institutions.[129] He was visited in Madrid and Soria by a number of world-class archaeologists.[130] In 1912 he was recognized for 5 volumes of his monumental Páginas de la Historia Patria por mis excavaciones arqueológicas [131] by Premio Internacional Martorell[132] and applauded for his work on Torralba by International Congress of Anthropology and Archaeology in Geneva the same year.[133] He was invited by the Ministry of Education to work on new law on excavations, which, adopted in 1911, prevented objects from being taken out of the country[134] and created Junta Superior de Excavaciones y Antigüedades y Comisión de Investigaciones Paleontológicas y Prehistóricas.[135] Headed a number of archaeological institutions himself.[136] Published studies on María Henríquez de Toledo, archbishop Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada and the Santa María de Huerta monastery.[137] In 1908 he entered Real Academia de Historia (invitation pending since 1898),[138] to join Real Academia Española in 1913.[139] Before his death de Cerralbo donated part of his archeological collection to museums.[140]

Hobbyist, collector, man of culture

From youth de Cerralbo contributed to Madrid periodicals, like Fomento Literario and La Ilustración Católica.[141] Active in La Alborada, a literary society founded by the son of his wife Antonio del Valle, he authored small pieces of prose and poetry; his El Arco Romano de Medinaceli has even made it to a contemporary Spanish poetry anthology.[142] His style, like this demonstrated in Leyenda de Amor, merged classical perfection of verse with romantic sentiment,[143] appealing to contemporary taste[144] though nowadays probably looking banal and bombastic. Spending lots of time in his preferred rural residence in Santa María de Huerta,[145] de Cerralbo practiced gardening and farming, in particular horse breeding.[146] He attempted to create a new lineage, a mixture of a pure English and a pure Spanish breed; in 1882 his yeguada won Primer Premio at the Madrid Exhibition, in 1902 his horses won prizes in Madrid and in Barcelona.[147]

Since his childhood de Cerralbo was infected by coleccionismo,[148] initially focused on numismatics,[149] but gradually broadened to collecting paintings,[150] arms, armor, porcelain and ceramics, rugs, tapestries and curtains, marbles, watches, lamps, sculptures, furniture, candles, drawings, rare books, stamps and other antiquities.[151] A tireless collectables hunter, Cerralbo traced them at auctions, antiquities shops and museums across Europe, purchasing also entire assortments from other people.[152] He amassed around 28,000 objects, his collection considered one of the most complete in Spain at the time. The contemporary press dubbed him El marqués coleccionista,[153] though his zeal was popular among the wealthy bourgeoisies.[154] Before his death de Cerralbo set up Fundación Museo Cerralbo, which displays most of the objects until today. The collection remains a good example of the 19th century private collectionist passion, somewhat undisciplined but delivering a sense of search for beauty and, possibly, quality of life.[155] In contemporary guidebooks the place is referred to as “a study in 19th-century opulence”, jammed with “fruits of the collector’s eclectic meanderings”.[156]

Legacy

De Cerralbo is credited for his archaeological contribution, consisting mostly of some key discoveries and introduction of modern excavation methods.[157] As a politician he is praised for employing new means of public mobilization and for conciliatory strategy,[158] rather atypical for Carlism. Finally, he is recognized as benefactor who donated part of his collection to public museums and who founded a museum himself. The critics note that he adhered to backward ideology[159] and refused to take sides during the moments of crisis (Third Carlist War, nocedalista conflict, La Octubrada, mellist schism), quoting poor health as an excuse.[160] They play down his collection as a chaotic and banal means of venting off his wealth.[161] He is charged with turning archeology into a vehicle of pursuing a nationalist discourse.[162] Finally, some indicate that de Cerralbo formed part of the oligarchy responsible for archaic social and economic conditions of Spain, also personally taking advantage of his privileged position versus the poor.[163]

See also

- Carlism

- Restoration (Spain)

- Electoral Carlism (Restoration)

- Carlos VII

- Jaime III

- Cerralbo Museum

- Archaeology

Footnotes

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, Salamanca y la Casa de Cerralbo, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, Genealogía de un marqués, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here, see also museo de cerralbo, geneanet, and geneallnet (none of the above complete). Official marquesado document is quoted in: Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922): biografía politica [PhD thesis], Madrid 2012, pp. 18-19

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, Retrato de juventud, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, La España que recibe a Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ Historia del Museo y su Fundador, [in:] Museo Cerralbo, available here

- ↑ Agustín Fernández Escudero, El XVII marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922). Primera parte de la historia de un noble carlista, desde 1869 hasta 1900, [in:] Ab Initio: Revista digital para estudiantes de Historia, 2 (2011), ISSN 2172-671X, p. 136

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 136, museo de cerralbo site

- ↑ The other titles inherited were 10th conde de Alcudia con Grandeza de España, 12th marques de Almarza, 9th marques de Campo Fuerte, conde de Foncalada, conde de Sacro Imperio, see here and obituary here

- ↑ like marques de Flores D’Avila, see Historia del Museo y su Fundador

- ↑ in Aranda de Duero, Ciudad Rodrigo, Vitigudino and Alba de Tormes districts

- ↑ though the heritage was divided among 17 descendants and Enrique inherited only some 7% of the wealth, see Sánchez Herrero, Miguel, El fin de los “buenos tiempos” del absolutismo: los efectos de la revolución en la Casa de Cerralbo, [in:] Ayer 48 (2002), pp. 85-126.

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 20, for the Monroyes see here

- ↑ Museo Cerralbo at Google Cultural Institute, available here; Jordi Canal i Morell, Banderas blancas, boinas rojas: una historia política del carlismo, 1876-1939, Madrid 2006, ISBN 8496467341, 9788496467347 p. 120 claims that in 1876 de Cerralbo’s wealth was estimated at 21 mills reales, most of it in the Salamanca province

- ↑ Historia del Museo y su Fundador

- ↑ Maria Ángeles Granados Ortega, Don Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa (1845-1922), XVII marqués de Cerralbo, [in:] Museo Cerrabo, Guida Breve, p. 9, for Angelin see his bios here

- ↑ Historia del Museo y su Fundador, p. 9

- ↑ They toured France, Portugal, Italy, Germany, Great Britain, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Austro-Hungary, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the Balcans

- ↑ Granados Ortega, p. 14

- ↑ 'Granados Ortega, p. 14

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, Las fiestas en Palacio, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ see genealogy, e.g. here

- ↑ The issue is far from clear. Consuelo Sanz-Pastor y Fernández de Pierola claims that Enrique has been born to the traditionalist family, see her El marqués de Cerralbo, político carlista, [in:] Revista de Archivos Bibliotecas y Museos LXXVI, 1/1973, pp. 231-270; Melchor Ferrer claims it was the influence of mother only, see his Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. I, Sevilla, 1959, pp. 153-154

- ↑ where he met Francisco Martín Melgar and Juan Catalina García, see Escudero 2012, p. 25

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 135

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 22-23

- ↑ The organization focused on art and archaeology, see Escudero 2012, p. 25

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 136, Escudero 2012, p. 33

- ↑ He made no intervention during that period, see Escudero 2012, pp. 34-35

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 136, Escudero 2012, p. 35

- ↑ Escudero 2012, pp. 41-48 finds no evidence that de Cerralbo either did or did not participate, though possibly his goods were periodically embargoed and he was one way of another forced to move out of Spain for some time, though it is not clear whether the measure amounted to exile

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 136, Escudero 2012, p. 35

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 36

- ↑ Raymond Carr, España 1808-2008, Madrid, 2009, p. 298; during the first carlist war 20% of aristocrats sided with Carlism, see Francisco y Bullón de Mendoza, Alfonso, Carlismo y Sociedad 1833-1840, [in:] Aportes XIX, Zaragoza, 1987, pp. 49-76.

- ↑ it is estimated that some 170 members of Spanish aristocracy (i.e. some 12% of the total) supported Carlos VII, Julio V. Brioso y Mayral, La nobleza titulada española y su adhesión a Carlos VII, [in:] Aportes 1 (1986), pp. 13-27

- ↑ and took part in the 1876 pilgrimage to Rome, see Escudero 2012, p. 51-52

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 30

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 137

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 63; Nocedal suspected the pretender of leaning towards a compromise with the Alfonsinos at the price of accepting liberalism, see Jacek Bartyzel, Bandera Carlista, [in:] Umierac ale powoli, Krakow 2006, p. 274, see also Javier Real Cuesta, El Carlismo Vasco 1876-1900, Madrid 1985, ISBN 8432305103, pp. 20-32

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 137; Escudero 2012, pp. 49-58

- ↑ Like the ultimately abandoned 1882 romería to Rome, see Escudero 2011 (1), p. 137

- ↑ Canal 2006, pp. 122-124; Escudero 2011 (1), p. 137; de Cerralbo many times confessed being uncomfortable with “dictadura nocedalista”, see Escudero 2012, pp. 58-69

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 69

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 137

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 138

- ↑ Having completed the required age in 1880 and having received permission from Carlos VII; Cerralbo’s entry into senate proved another point of conflict with the Nocedals, see Escudero 2012, p. 71-75

- ↑ he served until his death in 1922, though he was a rather passive member with only 3 interventions during 37 years, see Escudero 2011 (1), p. 137, Escudero 2012, p. 70, 75, 137

- ↑ or another body, Junta para la Conmemoración del XIII entenario de la Unidad Católica, see Escudero 2012, pp. 88-97, Escudero 2011 (1), p. 138

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 81-82, 99-123, Escudero 2011 (1), p. 139

- ↑ El Correo Español ceased to run in 1922, when with the death of Cerralbo it lost its key protector, spiritus movens and financial supporter, see Canal 2006, p. 128, Escudero 2012, pp. 125-140

- ↑ debe salir lo antes posible para desconcertar a los rebeldes que lo esperan para mucho más tarde; thed paper was designed as mi órgano oficioso, nuestro boletín oficial, la Gaceta carlista, quoted after Escudero 2011 (1), p. 139

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 138

- ↑ Like constructing a pyramide to commemorate 1300th anniversary of conversión de Recaredo. The project was abandoned due to opposition on part of the liberal government and lukewarm approach of the Catholic hierarchy, see Escudero 2011 (1), p. 140-141, Escudero 2012, pp. 140-166

- ↑ E.g. to the Basque Country, Navarre, Catalonia, Valencia, Murcia, Alicante, Burgos, Ciudad Real, see Escudero 2011 (1), p. 141, Escudero 2012, pp. 168-186 and 202-225, Canal 2006, p. 126-135

- ↑ The most reported were the so-called “sucesos de Valencia” in 1890, followed by unrest in Pamplona and Estella. Canal 2006, pp. 142-149, Escudero 2011 (1), p. 142, Escudero 2012, pp. 187-201

- ↑ A royal gift of watch used by Francisco de Austria-Este during the Napoleonic wars, Gran Cruz de Carlos III, Mayordomo Mayor title, Orden del Toisón de Oro, Orden del Espíritu Santo; Escudero 2011 (1), p. 138, Eduardo Valero, Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa en el Carlismo, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid available here, and Escudero 2012,, pp. 36-40

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), , p. 138

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 143

- ↑ Canal 2006, p. 123 claims there were 4 tasks ahead of Cerralbo: confronting Nocedal, building the party, generating popular support and integrating the La Fe periodical

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 143

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 143

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 244-245

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 251

- ↑ Canal 2006, p. 126-135

- ↑ Canal 2006, p. 129

- ↑ He set up Fiesta de los mártires de la Tradición, Escudero 2011 (1), p. 145, Escudero 2012, pp. 288-301

- ↑ Canal 2006, pp. 126-134

- ↑ Escudero 2012, pp. 259-260

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 85

- ↑ Historia del Museo y su Fundador; Jordi Canal, El carlismo. Dos siglos de contrarrevolución en España, Madrid 2004., pp. 242-243; Javier Real Cuesta, El Carlismo Vasco 1876-1900, Madrid 1985, ISBN 8432305103, 9788432305108, p. 136, claims that the number of juntas locales grew from 961 in 1892 to 2463 in 1896.

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 144-145

- ↑ "l'organizzazione era perfetta, come nessun altro partito l'ha in Spagna", reported the papal nuncio Rinaldini to Vatican shortly after 1900, Jordi Canal, Republicanos y carlistas contra el Estado. Violencia política en la España finisecular, [in:] Aportes 13 (1994), p. 76

- ↑ Canal 2006, p. 120; Real Cuesta 1985, p. 128, gives a somewhat different definition of "carlismo nuevo": to use the means offered by the democratic system to blow it up from within

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 146, Escudero 2012, pp. 320-331

- ↑ recently laid out in Rerum novarum; De Cerralbo seemed quite aware of the new, secular and mass tide; as early as in 1893 he confessed: La República se aproxima, la República va á triunfar, pero la República caerá envuelta en el descrédito, en la anarquía, en algo que se asemeja á la desolacion, y que hemos de salvar los verdaderos defensores del Altar y del Trono que simboliza la figura de nuestro Rey, quoted after Escudero 2012, p. 268

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 146

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 146

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 147-148

- ↑ E.g. nomination of José B. Moore Jefe de Estado Mayor de su Ejército de Cataluña, Escudero 2011 (1), p. 148, Escudero 2012, pp. 342-366

- ↑ some describe his position as ambiguous and his stance as marked by “duality”, torn between legalism and conspiration, see Escudero 2012, p. 529-530

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 361

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 148

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 368-382; some authors maintain the genuine reason was the discrepancy with the pretendent Canal 2004, p. 254 and Canal 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Agustín Fernández Escudero, El XVII marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922). Segunda parte de la historia de un noble carlista, desde 1900 hasta 1922, [in:] Ab Initio: Revista digital para estudiantes de Historia, ISSN 2172-671X, 4/2011, p. 70

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 68

- ↑ and Casteldefells, Santa Coloma de Gramanet, Igualada, Sardañola, Alcoy, Berga, Calella, Mantesa and Moncada

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 72, Escudero 2012, p. 383-402

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (1), p. 149

- ↑ Sanz-Pastor y Fernández de Pierola 1973, pp. 231-270 claims yes; Escudero 2011 (2), p. 69 and Escudero 2012, p. 394 claims no

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 72-73

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 69

- ↑ Ferrer 1959, p. 213, Escudero 2011 (2), p. 73-74, Escudero 2012, pp. 301-310 and 402-408

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 74

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 75

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 420

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 76

- ↑ Including Mella, Llorens and Cerralbo himself, see Escudero 2012, p. 421

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 77; renaming of the movement from Carlismo to Jaimismo came naturally, see Julio Aróstegui, Jordi Canal, Eduardo Calleja, El carlismo y las guerras carlistas, Madrid 2003, p. 97. See also Juan Ramón Andrés Martín, El caso Feliú y el dominio de Mella en el Partido Carlista en el período 1910-1912, [in:] Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie V. H. Contemporánea, 10 (1997) pp. 99-116.

- ↑ Vazquez de Mella, Tirso de Olazábal and conde de Melgar

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 439

- ↑ It is interesting to note that Correo Español, set up by de Cerralbo 24 years earlier, voiced – by mouth of its then editor-in-chief Gustavo Sánchez Márquez - against his nomination, see Escudero 2011 (2), p. 80

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 78-79. Clemente writes that de Cerralbo, deprived of political experience, owed his appointment to flattery, see Clemente, Historia general del carlismo, Madrid 1992, p. 358.

- ↑ Canal 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 79, Escudero 2012, p. 438-454

- ↑ Andrés Martín 1997, pp. 67-78, see also his El cisma mellista: Historia de una ambición política, Madrid, 2000, Clemente 1992, pp. 358-359. Indeed, there was no such thing as cerralbismo, especially compared to mellismo; oddly, it was de Mella who declared himself to be a “cerralbista”, Escudero 2012, p. 453

- ↑ Canals 2006, pp. 136-158

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 81, Escudero 2012, p. 458

- ↑ Ferrer 1959, pp. 45-61, Escudero 2011 (2), p. 81

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 475-478

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 465-472

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 83-84

- ↑ Gibraltar and Tanger being key points of conflict; Escudero 2012, pp. 481-482

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 84

- ↑ Escudero 2012, pp. 455-457

- ↑ like conde de Melgar

- ↑ Presidency of Junta Central passed temporarily to his deputy, Cesáreo Sanz Escartín, but later in 1918 Don Jaime nominated Pascual Comín y Moya political leader as his secretarío politico, soon replaced by Luis Hernando de Larramendi Ruiz and finally in 1920 by marques de Villores. Many consider health an excuse, see Ferrer 1959, pp. 89-94, Clemente 1992, pp. 359-361, Clemente, El carlismo en el novecientos español (1876-1936), Madrid 1999. pp. 64-66

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 86

- ↑ Escudero 2012, pp. 516-517

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 520

- ↑ Carmen Jiménez Sanz, Las investigaciones del Marqués de Cerralbo en el «Cerro Villar» de Monreal de Ariza: Arcobriga, [in:] Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie I, Prehistoria y Arqueología, t. 11, 1998, p 214

- ↑ by the way of his Santa Maria de Huerta monastery research; Jiménez Sanz 1998, p 215

- ↑ including analysis of ancient trade routes, geography and hydrology

- ↑ Jiménez Sanz 1998, pp 215-216

- ↑ Historia del Museo y su Fundador

- ↑ Like Alpanseque, Luzaga or Aguilar de Anguita; Jiménez Sanz 1998, p 214

- ↑ Jiménez Sanz 1998, p 218

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 77

- ↑ Jiménez Sanz 1998, p 219

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 77; compare de Cerralbo’s Arcobriga en El Alto Jalón, [in:] Descubrimientosarqueológicos, Madrid, 1909, págs. 106-132, De «Arcobriga». Del hogar castellano, estudios históricos y arqueológicos. Biblioteca Patria, vol. Clll, Madrid, s/d, pp. 91-124.

- ↑ Institut Français, the London Society of Antiquaries, Kaiserlich Deutschen Archäologischen Institut, Accademia Pontificia Romana dei Nuovi Lincei, the Bordeaux Académie Nationale des Sciences Belles Lettres et Arts, L’Institut de Paléontologie Humaine in Paris, Société Préhistorique Française and the Spanish Real Academia de Bellas Artes, see Escudero 2011 (2), p. 77

- ↑ like Émile Cartailhac, Henri Édouard Prosper Breuil, Horace Sandars, Adolf Schulten, Pierre Paris, Edouard Harlé and Hugo Obermaier, see Jiménez Sanz 1998, p 219 and Historia del Museo y su Fundador

- ↑ Granados Ortega, p. 12

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, El marqués literato y poeta, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ Jiménez Sanz 1998, p 214

- ↑ Historia del Museo y su Fundador

- ↑ Jiménez Sanz 1998, p 214

- ↑ Nominated vicepresident of Asociación Española para el Progreso de las Ciencias, president of Comisión de Investigaciones Paleontológicas y Prehistóricas, and vicepresident of Junta Superior de Excavaciones y Antigüedades, see Escudero 2012, p. 434

- ↑ Historia del Museo y su Fundador

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 75

- ↑ Escudero 2012, p. 434

- ↑ namely to Museo Arqueológico Nacional and Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Historia del Museo y su Fundador

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, El marqués literato y poeta, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ Granados Ortega, p. 11

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, El marqués literato y poeta

- ↑ in 1898 one of the press critics noted with melancholy: “what a pity that such a man dedicated himself to politics!”, Eduardo Valero, El marqués literato y poeta

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 78

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 77

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, XVII marqués de Cerralbo, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ Historia del Museo y su Fundador

- ↑ from his childhood he was collecting coins given weekly by his father, see Jiménez Sanz 1998, p 214

- ↑ His interest in painting focused on Spanish and Italian artists, mostly from 18th and 19th century, with clear preference for portraits and religious themes, see Granados Ortega, p. 20

- ↑ Granados Ortega, pp. 14, 19

- ↑ like marques de Salamanca; see Museo Cerralbo at Google Cultural Institute, here

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, El Museo Cerralbo y su mentor en el recuerdo de la Prensa española, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ Museo Cerralbo at Google Cultural Institute, available here

- ↑ Eduardo Valero, El marqués colectionista, [in:] Historia Urbana de Madrid, available here

- ↑ See Museo de Cerralbo entry by Lonely Planet, available here

- ↑ See Sanz, C. Pioneros: Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa, Marqués de Gerralbo, [in:] Revista de Arqueología, 182, 1996, pp. 52-57, Pilar de Navascues Bennloch, El Marqués de Cerralbo, Madrid 1997. J. A. Mohán, E. Cabré, El Marqués de Gerralbo y Juan Cabré, [in:] Boletín de la Asociación Española de Amigos de la Arqueología, 36, 1996, pp. 23-35. Pilar de Navascues Bennloch, El XVII Marqués de Gerralbo y su aportación a la arqueología española, [in:] G. Mora, M. Díaz-Andreu (eds.), La cristalización del pasado: Génesis y desarrollo del marco institucional de la Arqueología en España, Málaga 1997, pp. 507-513. M. Barril, M. L. Cerdeño, El Marqués de Gerralbo: un aficionado que se institucionaliza, [in:] G. Mora, M. Díaz-Andreu (eds.), La cristalización del pasado: Génesis y desarrollo del marco institucional de la Arqueología en España, Málaga 1997, pp. 515-527.

- ↑ Escudero 2011 (2), p. 89

- ↑ Even the highly sympathetic biographer feels obliged to note that de Cerralbo stuck to “archaic ideology”, see Escudero 2012, p. 530

- ↑ it is not clear what exactly was wrong with his health, and some suspect him of hipochondria, Escudero 2012, p. 27-28

- ↑ see critical reviews at tripadvisor reviews

- ↑ one author notes that "archaeologists continued to describe a past which the public wanted to hear, that is, a national past” and that “this nationalist discourse, in fact, became the preferred territory of the most anti-democratic, reactionary and socially most regressive ideological options. These took over the concept of Spain as a monolithic cultural unit which arose in the mid-nineteenth century", proceeding to list de Cerralbo among most typical and important representatives of the trend, Margarita Díaz-Andreu, The past in the present: the search for roots in cultural nationalism. The Spanish case, [in:] Justo G. Berramendi, Ramón Máiz, Xosé M. Núñez (eds.), Nationalism in Europe. Past and Present, vol. 1, Santiago de Compostela 1994, ISBN 8481211958, pp. 207-208

- ↑ Two years before death de Cerralbo sold houses and plots in Cerralbo to the renters at a price considered exorbitant and paid in installments until the 1950s, see Miguel Sánchez Herrero, De colonos a propietarios. Endeudamiento nobiliario y explotación campesina en tierras del marqués de Cerralbo (Salamanca siglos XVXX), Salamanca 2006, ISBN 8478004777

Further reading

- Historia del Museo y su Fundador, [in:] Museo Cerralbo website

- Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El caso Feliú y el dominio de Mella en el partido carlista en el período 1909–1912, [in:] Historia contemporánea 10 (1997), ISSN 1130-0124

- Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista. Historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788487863820

- Jordi Canal i Morell, Banderas blancas, boinas rojas: una historia política del carlismo, 1876-1939, Madrid 2006, ISBN 8496467341, 9788496467347

- Jordi Canal i Morell, La revitalización política del carlismo a fines del siglo XIX: los viajes de propaganda del Marqués de Cerralbo, [in:] Studia Zamorensia 3 (1996), pp. 233–272

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922): biografía politica [PhD thesis], Madrid 2012

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo. Una vida entre el carlismo y la arqueología, Madrid 2015, ISBN 9788416242108

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El XVII Marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922). Iglesia y carlismo, distintas formas de ver el XIII Centenario de la Unidad Católica, [in:] Studium: Revista de humanidades, 18 (2012) ISSN 1137-8417, pp. 125–154

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El XVII marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922). Primera parte de la historia de un noble carlista, desde 1869 hasta 1900, [in:] Ab Initio: Revista digital para estudiantes de Historia, 2 (2011), ISSN 2172-671X

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El XVII marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922). Segunda parte de la historia de un noble carlista, desde 1900 hasta 1922, [in:] Ab Initio: Revista digital para estudiantes de Historia, 4 (2011), ISSN 2172-671X

- Carmen Jiménez Sanz, Las investigaciones del Marqués de Cerralbo en el «Cerro Villar» de Monreal de Ariza: Arcobriga, [in:] Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie I, Prehistoria y Arqueología, t. 11, 1998, pp. 211–221

- Maria Ángeles Granados Ortega, Don Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa (1845-1922), XVII marqués de Cerralbo, [in:] Museo Cerrabo, Guida Breve

- Guadalupe Moreno López, El archivo de Enrique Aguilera y Gamboa, XVII marqués de Cerralbo, en el Museo Cerralbo. Propuesta de clasificación, [in:] Boletín de la ANABAD, 48 (1998), pp. 207–230

- Pilar de Navascués Benlloch, Cristina Conde de Beroldingen Geyr, El legado de un mecenas: pintura española del Museo Marqués de Cerralbo, Madrid 1998, ISBN 8489162972, 9788489162976

- Pilar de Navascués Benlloch, El XVII Marqués de Cerralbo y su aportación a la arqueología española, [in:] Gloria Mora, Margarita Díaz-Andreu, Margarita Díaz-Andreu García (eds.), La cristalización del pasado: Génesis y desarrollo del marco institucional de la Arqueología en España, Málaga 1997, ISBN 8474966477, 9788474966473, pp. 507–513

- Pilar de Navascués Benlloch, Carmen Jiménez Sanz, El Marqués de Cerralbo, Madrid 1998, ISBN 8481813435, 9788481813432

- Consuelo Sanz-Pastor y Fernández de Pierola, El marqués de Cerralbo, político carlista, [in:] Revista de Archivos Bibliotecas y Museos LXXVI, 1/1973, pp. 231–270

- Carmen Jiménez Sanz, Pioneros: Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa, Marqués de Cerralbo, [in:] Revista de Arqueología, 182, 1996, pp. 52–57

- María Luisa Cerdeño Serrano, Magdalena Barril Vicente, El Marqués de Cerralbo: un aficionado que se institucionaliza, [in:] Gloria Mora, Margarita Díaz-Andreu, Margarita Díaz-Andreu García (eds.), La cristalización del pasado: Génesis y desarrollo del marco institucional de la Arqueología en España, Málaga 1997, ISBN 8474966477, 9788474966473, pp. 515–527

- Eduardo Valero, El marqués coleccionista, [in:] Historia urbana de Madrid website

External links

Media related to Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Enrique de Aguilera y Gamboa at Wikimedia Commons- Cerralbo at the website of Spanish Senate

- Agustín Fernández Escudero. El marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922). Biografía política

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El XVII marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922) Primera parte

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El XVII marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922) Segunda parte

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, Cerralbo, church and carlism

- Carmen Jiménez Sanz, Las investigaciones del Marqués de Cerralbo en el «Cerro Villar» de Monreal de Ariza: Arcobriga

- El marques coleccionista at Historia Urbana de Madrid

- marquesado de Cerralbo

- family tree at geneanet

- family tree at geneallnet

- Museo Cerralbo official site

- contemporary Carlist propaganda (video); Cerralbo at 2:41 (standing)